Chapter 1. Brain Development: Adolescence

Synopsis

Brain Development: Adolescence

Author

S. Stavros Valenti, Hofstra University

Synopsis

In this activity, you will see animations and illustrations of the changes that occur in the brain during the teenage years. The relationship between these biological changes and adolescent behavior will also be explored.

REFERENCES

Kolb, B., & Whishaw, I. Q. (2001). An introduction to brain and behavior. New York: Worth Publishers.

Spear, L. (2000). The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 24, 417-463.

The Teen Brain

In many respects, a person is at the peak of his or her physical capacities in the teenage years. Consider the number of outstanding teenage athletes in fields such as gymnastics, figure skating, or tennis. Many teenagers are happy and well adjusted. They look forward to the privileges and responsibilities of adulthood.

While the teenage years may be a positive experience for some, adolescents are also at greater risk for drug and alcohol abuse, reckless driving, depression, and criminal behavior.

How can we explain this rise in problem behaviors during adolescence? Some recent research suggests that brain development and hormonal changes may hold important clues for understanding why adolescence is so exciting, and yet at times, so difficult for teens and their families.

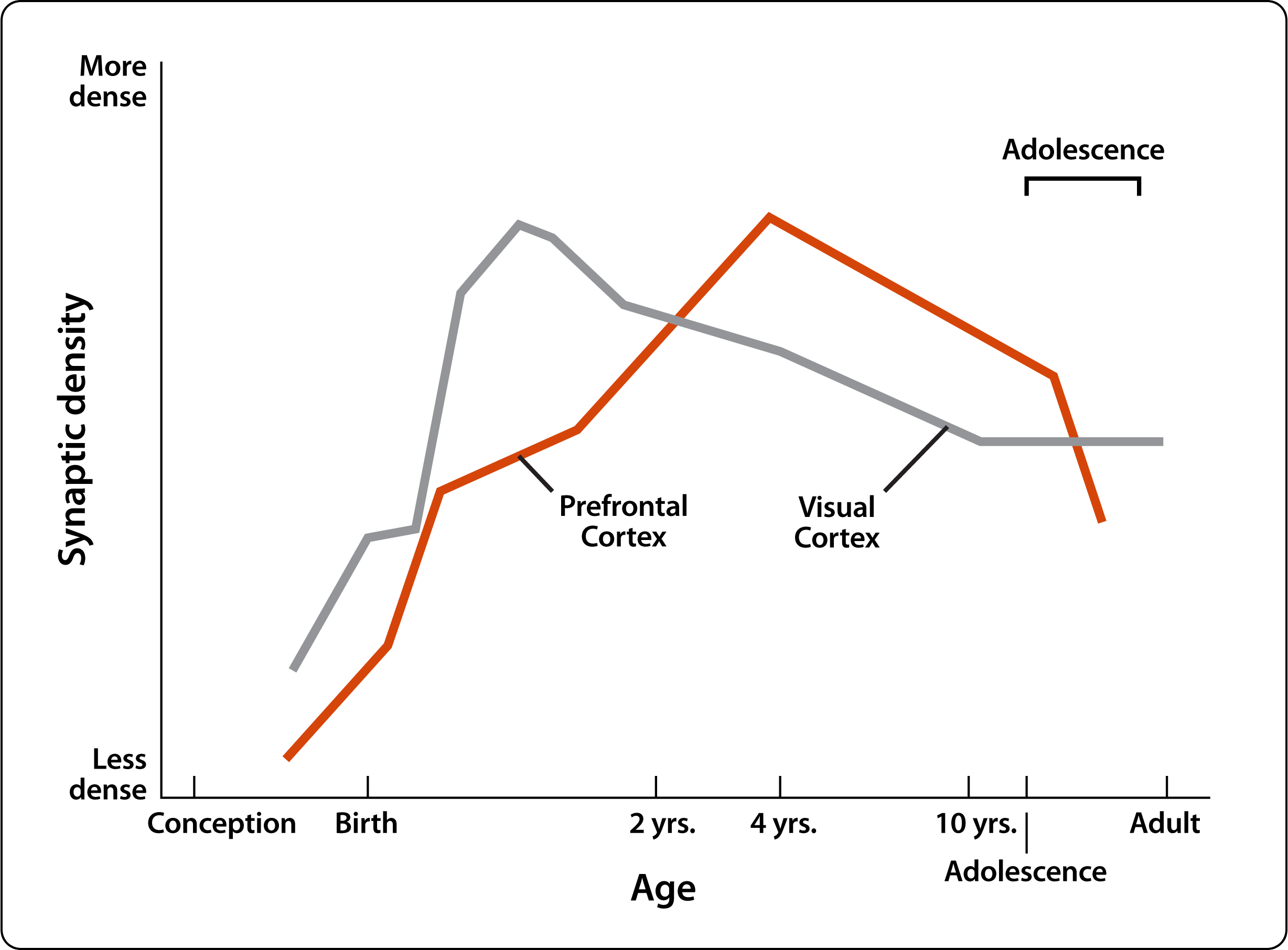

A Slow Growing Brain

The brain is still growing and changing during most of the teen years achieving its maximum size around the age of 18. At its peak, the brain weighs about 1.4 kilograms (about 3 pounds), which is about 4 times its weight at birth. Adolescence is a time of growth in the connections among neurons as well as a time of synaptic pruning and myelination. All of these developments act to further refine thoughts, actions, and behaviors and prepare the adolescent for adulthood.

The Prefrontal Cortex

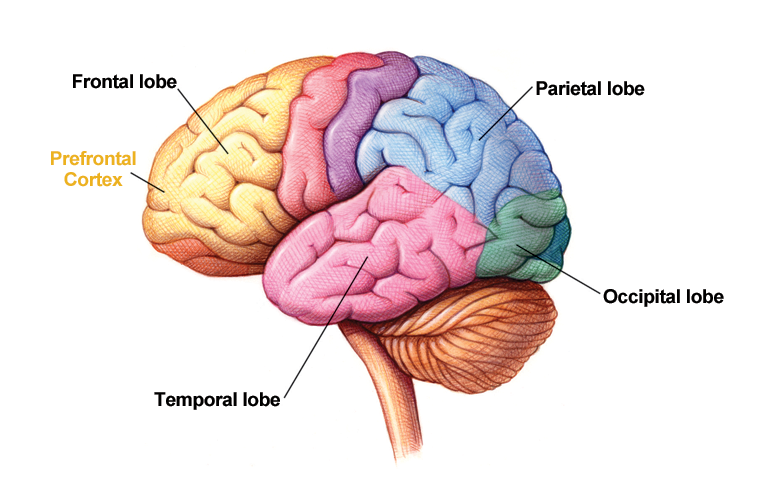

The brain centers for sensation and perception are well developed during infancy, but other areas of the brain take much longer to mature. The frontal lobe within the cerebral cortex (in particular, the prefrontal cortex) shows significant changes from mid-childhood through the early 20s. This area of the cortex is responsible for inhibiting impulses, focusing attention, and planning — in short, all of the behaviors that we associate with intelligence, responsibility, and emotional maturity.

1.

What aspect of brain development might help to explain why a teenager can usually perform better as a babysitter than someone ten or eleven years old?

Maturation of the Prefrontal Cortex: Synaptic Remolding and Myelination

Maturation of the prefrontal cortex is the result of two important changes at the microscopic level: myelination, which is the addition of myelin to the connecting fibers of neurons, and pruning, which is the remodeling of synaptic connections. Both of these changes yield a brain that processes information more quickly and efficiently.

Slowing of Metabolism

Teen brains demonstrate a slower metabolism, which is another characteristic of maturity. A preschool child’s brain burns calories at higher-than-adult levels (hypermetabolism) in order to build new connecting fibers, synapses, and myelin. As the process of synaptic pruning customizes the brain making it more efficient, the brain metabolism declines from age 10 years until about 20 years of age.

Emotional Versus Intelligent Control of Behavior

Some recent studies have suggested that there is a change in the balance of activity between the limbic system, which is involved in motivated behavior and automatic emotional reactions, and the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for deliberate and thoughtful behavioral control. The specific nature of the interaction of these brain centers is unknown, but it is safe to say, “the adolescent brain is a brain in flux . . .” (Spear, 200, p. 438).

Raging Hormones?

Along with the brain changes that occur during adolescence, a rise in the level of hormones in the bloodstream also occurs. Hormones produced by the adrenal glands that are believed to increase the overall excitability of the brain begin to rise around 7 years of age and reach a plateau in late adolescence. Increasing levels of hormones produced by the gonads, which are responsible for the bodily changes of puberty, are also related to slight increases in moodiness, aggressive behavior, and aggressive thoughts in both males and females (Spear, 2000).

While there is good evidence for the idea that hormonal changes are related to behavioral changes, recent research has shown that this connection is a modest one at best. There is little support for the commonplace idea that risky teen behavior is caused by “raging hormones”.

Brain and Behavior: What is the Connection?

What are we to make of these changes in the brain across adolescence? Researchers are careful to point out that “correlation is not causation.” Just because the brain is changing, it does not necessarily mean that these brain changes cause the unique behaviors of adolescence.

Researchers have offered some promising leads. The limbic system within the brain is involved in the way in which the brain experiences “reward” and “pleasure.” The observed shift in the balance of activity between the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex may be responsible for the well-documented decline in “pleasure” and “happiness” that is observed in early adolescence. Some researchers have described the adolescent as having a “mini reward-deficiency syndrome” that leads some to seek increased levels of stimulation through interaction with peers, risky behavior, and drug or alcohol use.

Brain and Behavior: The Role of Experience

Some researchers stress that the roots of adolescent risk-taking and impulsive behaviors stem from teenagers’ lack of relevant experiences and skills. Adults, after all, have many more years of experience with both the short and the long-term consequences of risky behavior.

Summary

In this activity, you have seen that the teenage brain is truly “a brain in flux.” Remodeling of synaptic connections with the help of new experiences sculpts a new brain. The metabolism of the brain decreases throughout childhood and adolescence, and the balance of activity appears to change between the structures in the brain’s limbic system and the prefrontal areas of the cortex.

We also know that adolescence is a time of increased interactions with peers, new experiences outside the home, and new demands for mature behavior. These new interactions and experiences help adolescents develop new skills for coping with increased stresses, but the growth of these skills takes time.

A full understanding of the causes of teen behavior will depend on continued study and research of the brain and of the unique experiences of teenagers.

Assessment: Check Your Understanding

2.

1. The growth of the brain during adolescence is caused by a rapid increase in the total number of neurons.

Assessment: Check Your Understanding

3.

2. Which of these brain changes is most likely to be observed in adolescence?

Assessment: Check Your Understanding

4.

3. What behavioral changes are thought to occur when the brain’s activity shifts from the limbic system to the prefrontal cortex in adolescence and early adulthood?

Assessment: Check Your Understanding

5.

4. What is the relationship between behavior and the well-documented increase in hormones during adolescence?

Assessment: Check Your Understanding

6.

5. Briefly describe the brain changes that occur in adolescence.

Congratulations! You have completed this activity.Total Score: x out of x points (x%) You have received a provisional score for your essay answers, which have been submitted to your instructor.