Chapter 1. Characteristics of Formal Thought

Synopsis

Characteristics of Formal Thought

Author

Thomas E. Ludwig, Hope College

Michelle Ryder, Daniel Webster College

Synopsis

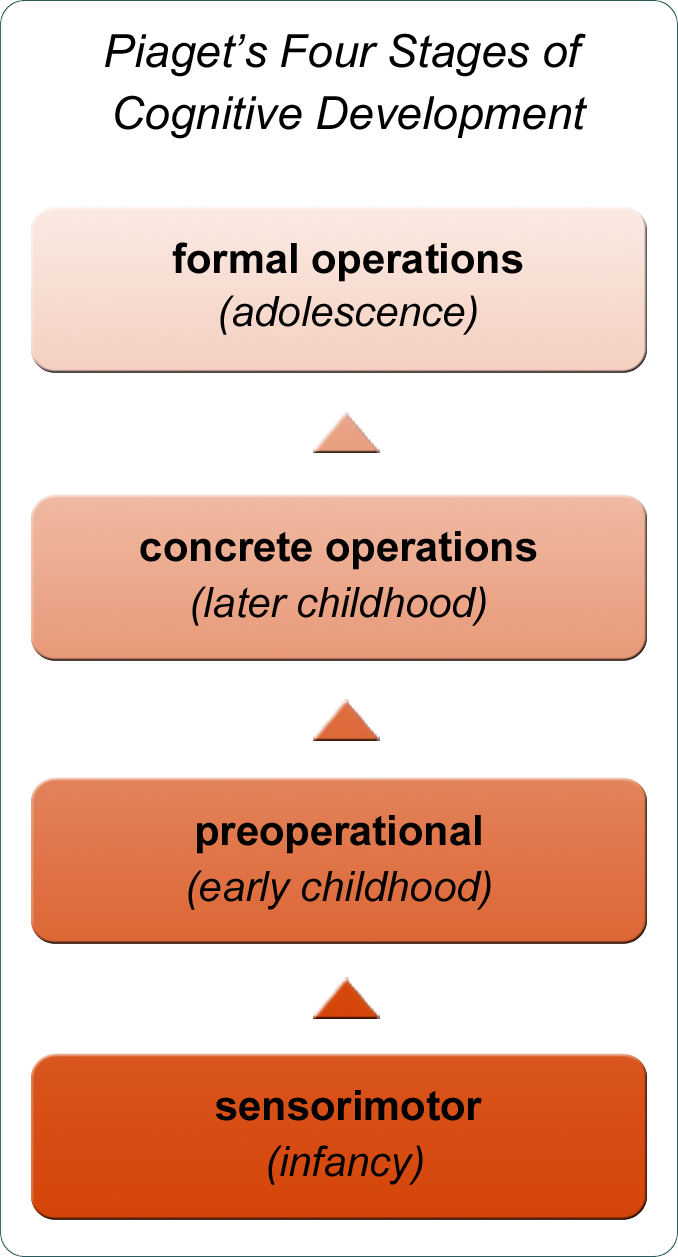

Formal operational thought is the fourth stage in Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. As part of this exploration of the main characteristics of formal operational thought, you will view video clips of children in two different stages of cognitive development attempting to solve a problem that requires systematic thinking and combinational logic. You will then consider the implications and limitations of formal operational thought.

REFERENCES

Blasi, A., & Hoeffel, E. C. (1974). Adolescence and formal operations. Human Development, 17, 344-363.

Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence. New York: Basic Books.

Kuhn, D., & Angelev, J. (1976). An experimental study of the development of formal operational thought. Child Development, 47, 697-702.

Leadbeater, B. J., & Dionne, J. P. (1981). The adolescent’s use of formal operational thinking in solving problems related to identity resolution. Adolescence, 16, 111-121.

Moshman, D. (1999). Adolescent psychological development: Rationality, morality, and identity. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wagner, J. (1987). Formal operations and ego identity. Adolescence, 22, 23-35.

Formal Operational Thought: Piaget’s Final Stage

When we reach adolescence, Piaget argued that our brain is reaching its final adult form. As each teen year passes, our capacity to learn and remember improves considerably, and we are able to handle more complex subject matter and do well on examinations covering a much greater amount of material. Thinking and reasoning also improve during these years. Adolescence marks the transition to the fourth and final stage in Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development.

Piaget proposed that we develop the capacity for formal operational thought in our teen years. In adolescence, this newly developed thought process enables us to apply logical reasoning to a wider range of problems as we begin thinking about the underlying structure of the problem rather than simply about the concrete objects in the problem. Unlike the younger child who is still tied to the concrete reality, the adolescent is able to consider possibilities as well as reality by reasoning logically about abstract, hypothetical situations.

Systematic Reasoning

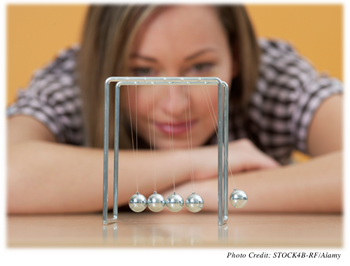

A key aspect of formal operational thought is systematic thinking, which is the ability to reason carefully through a sequence of steps without skipping a step. Piaget tested this way of thinking with a task known as the pendulum problem. He gave children the assignment of figuring out what determines a pendulum’s oscillation rate, which is the rate at which a pendulum swings back and forth.

He showed these children how to manipulate four factors that have a possible influence on the oscillation rate:

1. length of the string (short or long);

2. amount of weight (heavy or light);

3. point of release (high or low);

4. force of release (drop the weight or push it).

Solving the Pendulum Problem

Researchers find that the pendulum problem separates the concrete operational children from the formal operational teens. Concrete operational thinkers approach the task haphazardly. Manipulating the variables almost at random, they rarely arrive at the correct solution. For example, an eight-year-old might first try a heavy weight with a long strong and then a lighter weight with a short string and mistakenly conclude that the weight determines the pendulum’s oscillation rate.

In contrast, formal operational thinkers approach the task systematically manipulating one factor at a time while holding all other factors constant. A 14-year-old might first try a heavy weight with a long string and then a lighter weight on that same string while being careful to release the weight at the same height and with the same force both times. This 14-year-old might then repeat the process with the short string and then move systematically through the other variables until she has reached the correct conclusion that only the length of the string influences the oscillation rate!

Combinational Logic: The Sandwich Game

Another aspect of formal operational thought is combinational logic, which is the ability to generate all possible combinations of variables in order to solve a problem. Researchers often use a task called the sandwich problem to test combinational logic. The researcher gives the subject a set of four sandwich ingredients (bread, meat, cheese, and lettuce) and asks how many different kinds of sandwiches can be made with these ingredients.

Most elementary school-aged children in the concrete operational stage have trouble with the sandwich problem. They generate some of the possible sandwiches, but they overlook other combinations. They sometimes repeat the same combination two or three times. Play the video clip to observe how, 14-year-old Juana, a concrete operational thinker, approaches this task. While you watch, think about the strategy that the child is using.

Combinational Logic in Adolescence

Now, let’s watch a formal operational thinker at work on the sandwich task. In contrast to younger children, teens in the formal operational stage find it easy to generate all the possible combinations. They often follow a strategy of laying out the sandwiches in rows and columns to make sure that they do not overlook any of the combinations.

Play the video to observe 19-year-old Deborah performing the sandwich task. Again, while you are watching, think about the strategy that she is using.

Implications of Formal Operational Thought

While formal operational thought may be helpful for planning sandwich menus, it is crucial for the demanding science and mathematics classes in high school. In particular, the ability to generate all possible combinations of variables and to step systematically through those combinations to test them underlies much of scientific research.

The same formal operational thought processes that enable adolescents to tackle complicated science problems also help them to function as more flexible, resourceful thinkers outside the classroom. This new reasoning power is evident in adolescents’ pondering and debating such abstract topics as human nature, good and evil, truth and justice, right and wrong. These thought processes also lay the foundation for the struggle to define one’s identity, or one’s definition of self that includes the values, beliefs, and ideals that guide behavior.

Limitations of Formal Operational Thought

Although Piaget’s theory of cognitive development continues to be influential, contemporary developmental psychologists have found some limitations in this theory.

1.) Piaget underestimated the importance of culture and education in promoting intellectual development. Studies testing adolescents and adults from non-industrial societies suggest that in those cultures, only a small minority of teens and adults can pass Piaget’s tests of formal operations. Based on this evidence, it seems logical to conclude that some minimum education in math and science may be a prerequisite for formal operational thinking.

2.) Piaget overestimated the number of people who actually master formal operational thought. Recent research has shown that the development of formal operational reasoning ability is far slower and less complete than Piaget believed it to be. These cognitive gains are not always accomplished during adolescence nor are they necessarily achieved by all people.

Limitations of Formal Operational Thought (continued)

Formal operational thought is not a comprehensive way of thinking. It is more likely to be demonstrated in some domains but not in others. For example, a doctor may demonstrate formal operational thinking on problems related to medical emergencies, but he may fall back on concrete operational thinking when reasoning about why his car will not start.

While most researchers believe that the capacity for formal operations represents a genuine change in the quality of adolescent thinking and is a change that will prepare teens for successful adaptation to the world of adulthood, there is a wrinkle in this theory. Along with the new cognitive abilities of adolescence appears an enhanced capacity for self-centeredness. This adolescent egocentrism is the belief that an adolescent’s own psychological experiences are unique. For example, many teens may be convinced that no one has ever loved as deeply or been hurt as badly as they have. The invincibility fable is a component of this egocentrism that describes a common adolescent belief that he/she is immune to common dangers that apply to ordinary people. This false sense of security that is responsible for adolescents engaging in risky behaviors, such as street racing, drinking and driving, or unprotected sex, accompanies the development of formal operational thinking. It is difficult to assess how these thought processes – one thought process representing systematic, hypothetical logic and the other representing self-absorbed, even irrational thinking – interplay with each other.

Assessment: Check Your Understanding

Question 1.1

GVygX9sJM9Aph0/qTMOFD1dcelL2NHTDwMHL4oSSDxg3Eme6w9d2ohto8U9zBo7GDAbGkCfVZpWFkteUNGDw++wUK+rgwynaueUIOiaHgoQT+QONSbqZr9RUxngKocOM4xarnGw+9zdbpvVvQMhYOfg7x/aYApOU0MIQlI3I/P+Xkw68Y2J982mS0l4+mghkwoLhvxEJH0YnzLto02hokBZhsEvevvczm8Mxf5mtelVCpokL1GKnB1CefXsaAZatRkDi7b28O0k=Assessment: Check Your Understanding

Question 1.2

LmLFE+QX7nLHkh7qE8GOErYqQQjTb7lgf+i9Gja51COe7ajdb7jeJMwnUek0lf7FwaiDOeEKDtPmlX4xKTtcnSMy1MtLARu8ahCz64RklJM8IbOrO0AGDvd83GVC5C1AQxulG6HUcsXgAs1KgrEpuBHVSxyceoFBNEbMwS6XZ4uLYecr4sS57BNBZVv5ehaKkINmagwNvij3LMIctaug6BwIRZ2NDY+6sawZgCMrCI3dpxRCFpYHcOHomUVS7zE8k6sbaA2mUoWwnbb1ERx93w==Assessment: Check Your Understanding

Question 1.3

kZTksnUw5Tlx5WTwh+E+Ef0IKgcmj539oZK42/e1QagHn5ynfPoc+/L4mYwXzoxvtvZmUgkEexzxUw7/A15FLNNuwx0SZO/7Zp7vAeecvY/SRy9nYKd7Tf7uoUlQd6ZGAZjZsFhlIfSGS9pYs/cPV1o9xdT2mkU6eVfqb0WsY9f5IsFwuICLVKfyhbC/n0pELGzHSTbEbeyExjsFnIHIpdTC/bRYE8OyGPzMI/td6QJlDiQDj6+cS02ZI/wYCYK42/AsJyTQyp9n64fFAssessment: Check Your Understanding

Question 1.4

xJOA4G31YgS+uWlvevGTTrVpixD7bO4I95/6V7WGs3+wgZojnTUzRjOtEkVkL0K/wTD8cTHPnBj+5naEt5I1Do/XQ2CP1xO5dqBa8sneA916+FY1Q9CmEvAAa/PxDl1cO9i/SdsZLrfzGN17e/39KWwRA+yEmR9n8uy6w2sPVw5oqDRp+xHk44zdLTl0lOkdpCmDws/d3XYXR4/e0Hx2LezL4aFprgF+cuDatoFBDDdQYQJyCongratulations! You have completed this activity.Total Score: x out of x points (x%) You have received a provisional score for your essay answers, which have been submitted to your instructor.