Chapter 1. Signs of Aging

Synopsis

Signs of Aging

Author

Thomas E. Ludwig, Hope College

Martina Marquez, Fresno City College

Synopsis

In this activity, you will explore aspects of aging. We will take you on a tour of the aging body while pointing out the signs of aging in appearance, the senses, physical abilities, and mental functioning. You will hear some older adults discuss their experiences with the aging process.

REFERENCES

Baltes, P. B., & Baltes, M. M. (Eds.) (1990). Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Baltes, P. B., & Graf, P. (1997). Psychological aspects of aging: Facts and frontiers. In D. Magnusson (Ed.), The life span development of individuals: Behavioral, neurobiological, and psychosocial perspectives (pp. 427-460). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bienenfeld, D. (1990). Physical changes with aging. In D. Bienenfeld (Ed.), Verwoerdt’s clinical geropsychiatry (3rd ed., pp. 3-16). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkens.

Chesky, J. A. (1987). Linking mind and body: Biobehavioral aspects of aging. In G. Lesnoff-Caravaglia (Ed.), Handbook of applied gerontology (pp. 143-154). New York: Human Sciences Press.

Corso, J. F. (1987). Sensory-perceptual processes and aging. In K. W. Schaie (Ed.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics, Vol. 7 (pp. 29-55). New York: Springer.

Farkas, K. J. (1984). Senescence. In F. J. Turner (Ed.), Adult psychopathology: A social work perspective (2nd ed., pp. 174-193). New York: Free Press.

Faubert, J. (2002). Visual perception and aging. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 56, 164-176.

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/medlineplus.html

https://www.apa.org/research/action/memory-changes.aspx

Jarvik, L. F. (1975). Thoughts on the psychobiology of aging. American Psychologist, 30, 576-583.

Leaf, A. (1973). Getting old. Scientific American, 229, 44-52.

Leventhal, E. A. (1994). Gender and aging: Women and their aging. In V. J. Adesso, & D. M. Reddy (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on women’s health (pp. 11-35). Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis.

Nordhus, I. H., VandenBos, G. R., & Berg, S. (1998). Clinical geropsychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Rubert, M. P., Eisdorfer, C., & Loewenstein, D. A. (1996). Normal aging: Changes in sensory/perceptual and cognitive abilities. In J. Sadavoy & L. W. Lazarus (Eds.), Comprehensive review of geriatric psychiatry (2nd ed., pp. 113-134). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Saxon, S. V., & Etten, M. J. (1987). Physical change and aging: A guide for the helping professions (2nd ed.). New York: Tiresias Press.

Whitborne, S. K. (2001). The physical aging process in midlife: Interactions with psychological and sociocultural factors. In M. E. Lachman (Ed.), Handbook of midlife development (pp. 109-155).

Whitbourne, S. K. (2002). The aging individual: Physical and psychological perspectives (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Primary and Secondary Aging

Researchers distinguish between primary aging and secondary aging. Primary aging is the normal, irreversible, biological changes that occur universally in all organisms. Secondary aging is the result of disease, hereditary defects, or environmental factors.

Although aging looks different in each individual, the deteriorative processes of primary aging are the same. As all cells age, their structural framework gets stiffer and thicker. They have a harder time communicating with each other and generating enough energy to perform their tasks. Gradually, these tiny changes accumulate, and over time, cells and whatever organs they make up break down and/or become less efficient.

While there is no way to prevent primary aging, some aspects of secondary aging are less inevitable. Some contributors to secondary aging, such as an inherited tendency toward a particular disease or health problem, environmental pollution or contamination where one lives, or lack of education about dangerous substances, are not necessarily the result of an individual’s negligence. However, other secondary aging influences, such as smoking, lack of exercise, poor eating and sleeping habits, or disregarding medical advice, are factors that are presumably within an individual’s control. Researchers and health care and public health professionals put a great deal of energy toward minimizing or even preventing secondary aging factors.

1.

In the space below, write a quick description of how you think primary and secondary aging will one day affect you.

Aging Begins in Early Adulthood

Exactly when do people start aging? As soon as overall physical growth stops (generally in the early 20s), senescence actually begins. Now, this information is not intended to scare you. In literal biological terms, any cell or organism reaches a developmental peak after which no more or minimal growth is possible. It is at that point that deterioration begins. As you can tell by observing the people of various ages in your life, this deterioration is a slow and gradual process in most cases, and there are even steps that individuals can take, such as keeping an exercise routine, keeping the mind active and engaged, or maintaining a healthy body weight, to slow the effects of secondary aging. Because aging is a complex process influenced by many biological and environmental factors, no two people age in exactly the same way.

Age-Related Changes from Early to Late Adulthood

Signs of aging include changes in appearance, in the effectiveness of the senses, and in physical and mental functioning.

In early adulthood, age-related changes may be barely noticeable at all. For example, younger children may be ever so slightly better or faster at childhood memory games than their early adult opponents. While many elite and professional athletes are in their primes during their early adulthood years, they train hard to maintain and increase their stamina, balance, and coordination. In some cases, younger children and adolescents may come by these talents more naturally and more easily. These minor aging changes are so subtle that they certainly do not require any lifestyle adjustments.

In middle adulthood, most people become aware of some changes in appearance and sensory capabilities. Those in middle adulthood may discover new fine lines and wrinkles, that reading without glasses becomes difficult or impossible, or that keeping a healthy body weight calls for paying greater attention to nutrition and exercise. While those in middle adulthood are likely to notice these changes, these changes do not generally affect quality of life.

At some point in late adulthood, the changes associated with aging begin to affect lifestyle and behavior to some degree. Changes in hearing may mean turning the volume up on the radio, telephone, or TV, asking people to speak louder and more clearly, or just accepting that parts of conversations may be missed. In some cases, a hearing aid may be required. Aches and stiffness may make certain exercises and activities painful. Driving patterns may be adjusted as changes in vision and concentration may affect an older adult’s confidence behind the wheel.

Aging and Appearance: Skin and Hair

Changes in appearance are inevitable as we move through adulthood. The skin becomes dryer, thinner, less elastic, and more wrinkled. Age spots, or permanent darkening of the skin as the result of sun exposure, begin to appear. While loss of hair is generally more typical in men, the hair of both men and women becomes grayer and thinner with age. While these changes in appearance are certainly not life threatening, most people are not often pleased with these developments. However, these age-related changes generally occur gradually, so people may have some time to adjust to their new look.

Play the video to hear several older adults talk about these changes.

Aging and Appearance: Shape

Older people undergo a change in body shape. Body fat redistributes and tends to collect in the hips, in the torso creating a “pot belly” or “paunch,” and in the lower face creating the dreaded “double chin.” Like the age-related changes in skin and hair, these changes in body shape are more of a nuisance than they are a serious health problem.

Play the video to listen to several older adults discuss changes in their shape and size.

2.

Which of the following statements about body shape applies to most older people?

Aging and Appearance: Size

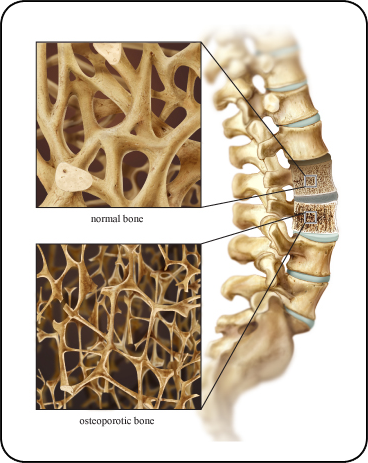

An alarming fact…once people stop growing, they start shrinking! This becomes very noticeable in late adulthood. Many older people are more than an inch shorter than they were during early adulthood because of the settling of the vertebrae and compression of the disks. Many older adults, particularly older women, develop a “stoop,” or a bend in the upper back. Often this stoop is the result not of primary aging but of a disorder called osteoporosis, which is a loss of calcium that leaves the bones very porous and brittle and can cause some of the vertebrae in the spine to collapse.

3.

Of the following, which would NOT be true of an older adult with osteoporosis?

Aging and Sensory Changes: Hearing

Some hearing loss is a normal part of the aging process. Environmental factors, such as exposure to exceptionally loud noises (i.e. gunshots, explosions) or prolonged exposure to moderately loud noises (i.e. jackhammers, engines, factory noises), will contribute to even greater hearing loss. Because of noisier work environments for men, men used to typically begin to show hearing loss at age 30 and women at around age 50. This 20-year disparity does not necessarily hold true anymore as the work and recreational activities of men and women are now more similar than they used to be.

More high-frequency tones than low-frequency tones are lost as we age. Hearing loss may not diminish the enjoyment of music, which includes many low-pitched, deeper tones, as much as it may impede the ability to perceive human speech, which includes many high-pitched tones especially with consonants “s,” “k,” or “t”. The general tendency is for older adults to have more difficulty understanding conversations especially if there is background noise. Therefore, these sensory changes affect the elderly more seriously than changes in appearance do because age-related hearing loss may impair a person’s ability to communicate and interact productively with the world.

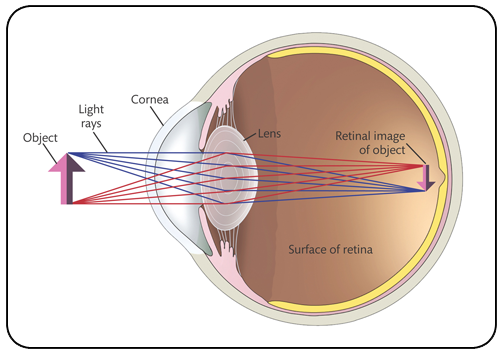

Aging and Sensory Changes: Vision

The majority of adults start to experience vision changes after age 40 and beyond. As the eye’s lens becomes stiffer and the eye muscles weaken, the ability to focus on small objects up close becomes increasingly difficult, a condition called presbyopia. Reading glasses or contacts become needed by almost all adults sometime after 40 if not required before.

The lens is not the only eye structure to change with age; all structures of the eye change over time. Pupils shrink as you age so older eyes react more slowly to changes in light and darkness. Glare may become a problem, and night driving can become difficult because the eye cannot adjust to bright lights against the darkness. An older lens may start to discolor making it difficult to perceive differences in colors. Older eyes may sink further into the sockets. That new position in addition to the weakening of the muscles controlling the eye might restrict peripheral vision reducing the overall field of vision.

Eye conditions and diseases of the eyes become more common with age. Tear production decreases over time. While dry eyes are easily treated, untreated dry eyes can lead to infections, scarring, and inflammation that can affect vision. While not considered normal age-related changes, the risks for serious eye disorders, such as cataracts, glaucoma, and macular degeneration, all increase with age.

Play the video to listen to older adults discuss changes in their vision.

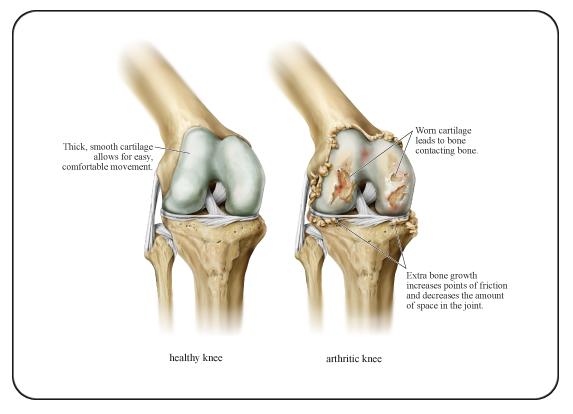

Aging and Physical Functioning: The Skeletal System

As people move into late adulthood, they lose muscle strength and joint flexibility. It becomes harder for older adults to perform strenuous activities that involve lifting and stretching. Osteoarthritis is a common development in older adulthood. Osteoarthritis is a breakdown of cartilage, which is the smooth coating on the ends of bones in the joints, and leads to joint inflammation, stiffness, and pain.

4.

Which of the following statements may apply to an older adult with osteoarthritis?

Aging and Physical Functioning: The Heart and Lungs

Lung capacity declines with age. Muscles and lung tissue lose their tone so that lungs lose the ability to completely expel all carbon dioxide. This leaves less room for taking in oxygen, and as a result, less oxygen is available for circulating throughout the body. The heart’s pumping capacity also declines with age as the heart rate slows a bit and the heart muscles thicken and become more rigid thereby reducing its ability to move blood as effectively.

Primary aging contributes to much of the deterioration in the heart and lungs. However, secondary aging factors, such as smoking, lack of exercise, or genetic tendencies, may accelerate the decline of these tissues. While the degree of these changes to the heart and lungs may affect older adults’ abilities to engage in some strenuous activities, those in older adulthood can still retain very physically active lives especially if they have remained active throughout their lives.

In addition to these normal age-related changes, many older adults are at greater risk for various problems and diseases, such as angina, arteriosclerosis, blood clots, lung infections, and abnormal breathing patterns.

Play the video to listen as older adults discuss changes to their physical energy level and mobility.

Old Age and Mental Allocation

We have reviewed how aging affects the body, but we have not explored how aging affects the brain and cognitive ability. Research points to the greatest age-related changes in memory and attention. Like other organs and structures, the brain does change as the result of decreased blood flow as we age. Also like other organs and structures, how the brain function changes with age differs in every individual. While there is cognitive decline in age, it is not as pessimistic as it sounds as the brain is a very flexible organ that can be trained and “exercised” even in old age. Research into how the brain ages contributes to a better understanding of how to keep the brain active and high-functioning well into late adulthood.

Play the video of research conducted in Berlin in which older adults were asked to memorize a list of words while they were walking a course.

5.

According to this video clip, what did the experiment show? According to the researcher, what do the findings mean for older adults? With this information, what advice might you give to an older adult that you care about to help him/her stay mentally active?

Conclusion: Making the Most of Each Stage of Life

We live in a youth-oriented culture that values smooth skin, slim and athletic bodies, and active lifestyles. As we age, our bodies will inevitably change in ways that move us away from this youthful ideal.

However, older adults are smart and resourceful, and most have found ways of compensating for these changes. The net result is that rates of happiness and satisfaction with life are just as high among older adults as among young and middle-aged adults.

6.

After having completed the activity, how do your feelings about aging compare to what you wrote at the beginning of the activity? Please explain how and why your feelings may have changed or stayed the same.

Assessment: Check Your Understanding

7.

1. When does senescence begin?

Assessment: Check Your Understanding

8.

2. In contrast to secondary aging, primary aging includes changes caused by:

Assessment: Check Your Understanding

9.

3. Age-related hearing changes are likely to affect an older adult’s enjoyment of music but not likely to affect an older adult’s ability to engage in conversation.

Assessment: Check Your Understanding

10.

4. Pain due to cartilage breakdown occurs because of:

Assessment: Check Your Understanding

11.

5. Age-related changes cause much unhappiness in late adulthood as quality of life suffers tremendously.

Congratulations! You have completed this activity.Total Score: x out of x points (x%) You have received a provisional score for your essay answers, which have been submitted to your instructor.