Chapter 1. Childhood Obesity

Introduction

Childhood Obesity

Author

Cathleen Erin McGreal, Michigan State University

Synopsis

In this activity, you will look at the problem of childhood obesity and explore some of its possible causes as well as some of its remedies. During the activity, you also will view videos in which children who have struggled with obesity describe themselves and their experiences of being overweight.

1.1 Overweight Children: A Health Issue “Bigger Than All of Us”

Sharron Dalton (2004), a professor specializing in food choice behavior and weight management, likes to quote a nurse’s provocative phrase. At a conference on childhood obesity, the nurse said, “It is bigger than all of us.” Sad but true, the problem of childhood obesity has been growing—not only in the United States but also around the world. Looking at U.S. statistics, Robert Cornette notes (2011) that 4% of baby boomers were overweight children, as compared to approximately one third of today’s youth who will be overweight before adulthood.

In the last four decades of the 20th century, the number of overweight children in the United States increased dramatically. For U.S. children aged 6 to 11 years, the percentage of children who were obese jumped from 4 percent to 16 percent. Mary Catherine Mullen and Jodie Shield (2004), two registered dieticians who recently wrote a book published by the American Dietetic Association, report that the recent rise in the number of overweight children occurs in all SES (socioeconomic status) levels (Mullen & Shield, 2004). Even children younger than 6 years show a higher incidence of becoming overweight and obese.

Mullen and Shield use the term “globesity” to indicate that childhood obesity has become a worldwide problem. In England, the rates of overweight children doubled in just a decade. In third world countries, children from higher SES families are at greater risk. Allison Collins and Rebecka Peebles (2011) summarize statistics from the first decade of the 21st century that show that this health challenge has intensified. In fact, across the globe, there are 22 million children aged 4 and under who are classified as obese. A renewed focus in the next decade is on obesity prevention.

Which of the following BEST describes the statistical pattern of obesity in U.S. children?

1.2 Obesity: From a Child's Point of View

Obese children are more susceptible to health problems throughout their lives if they remain obese. Unfortunately, issues related to long-term health, such as liver disease and cardiovascular problems, are often too far in the future for children to grasp. For a child of 10, getting a driver’s license feels like a lifetime away. What might matter most to an overweight child of 10 is being part of a particular group, feeling welcomed by peers at school, or getting invited to a birthday party. Once at a birthday party, an obese 10-year-old might wonder what it would be like to play with the other children who are crawling through the tubes in The Fun Zone. He/she might worry that other children in the tubes will comment on his/her “big bottom.” The obese child might then prefer to stay out of the tubes altogether. The fear of being teased can actually prevent obese children from enjoying their peers.

Relationship aggression (insults or social rejection) is directed at many overweight children. NBC Today Show star, Al Roker, felt self-doubt and emotional pain because of the taunts he suffered as a “husky” boy (Rimm & Rimm, 2004). Roker notes that movies and television shows ridicule those who are overweight, just to get a laugh. You might think that since there are more obese children today that the stigma toward obesity has diminished from the baby boomer days when fewer children were obese. Unfortunately, the emotional toll has grown worse for this century’s kids (Cornette, 2011).

1.3 Obesity and Health Problems

Parents are concerned about the long-term problems that their obese children face. Their concerns are realistic. A 2005 article by Jay Olshansky and his colleagues, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, drew considerable media attention when it outlined the possibility that today’s children could have a lower life expectancy than their parents’ or grandparents’ generations due to the health risks associated with excessive weight. Click on each health problem below to find out whether it poses a risk to someone who is obese—and if it does, what association that disease has with obesity.

Heart Disease

Yes! Heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and premature death are associated with obesity.

Stroke

Yes! Heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and premature death are associated with obesity.

Type 2 Diabetes

Yes! Heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and premature death are associated with obesity.

Premature Death

Yes! Heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and premature death are associated with obesity.

If a child begins to have health problems related to obesity at two years of age or at eight years of age, then serious health risks begin much earlier in life. What interventions are possible to prevent weight problems in the first place? What changes can help families who want to improve and enhance their health and well-being?

1.4 Beyond Hunger: Humans in a Land of Plenty

It would be great to have a signal system that changed our taste preferences. A possible interior monologue would go something like this:

“Looks like there is plenty of food and there is going to be abundant food in the foreseeable future. The layer of fat in my body is at an optimal level. The regulatory system and the sensation/perception system regarding taste and smell will now change so that foods high in sweets and fats will be rejected as not very appealing foods.”

Unfortunately, it doesn’t work that way. Foods that are no longer beneficial are still appealing.

Play the video to listen to some older children and their parents discuss food choices and some problems that overweight children face.

Do you often eat foods that you don’t consider healthy? If so, what thoughts direct you to these food choices? How do you compare your relationship to food with the relationship the children discuss in the video?

1.5 Beyond Hunger: What Makes Us Want to Eat?

It should be simple. Most of us know which foods we should eat. Even young children can recite the names of some healthy foods. Why don’t we eat these foods? Why do sweets seem so appealing? Why do we continue eating even when we’ve had enough?

The answers are complicated and involve the interaction of genes and environment. One explanation comes from evolutionary psychologists who have looked at the ways in which human tendencies have been influenced by natural selection. Babies scrunch up their faces in disgust when bitter tastes are placed on their tongues. Scientists think that this dislike may have evolved because many poisonous plants have bitter tastes. Potential ancestors who thought that these plants would make a good breakfast didn’t get a chance to pass on their genes!

All humans are born with a preference for sweets. In fact, breast milk is sweet! Early in human history, those individuals who preferred sweets reproduced; those who built up stores of fat survived when food was scarce. The genetic legacy of our human ancestors continues today. As a species, we like sweet tastes and salty tastes. Our tendency is to store fat for a famine that is now, in many countries, unlikely to come.

1.6 Beyond Hunger: What Makes Us Want to Eat? (continued)

In addition to genetics, our environment has a strong influence on our food choices. Think about a special event in your childhood. After a great report card or a dance recital, how did you celebrate? Did your family go out to dinner or pick up a special treat? Was there a time when you didn’t get picked for a part in a class play or when you weren’t invited to a birthday party? Was food a part of the comforting process? Was dessert always included at family meals? Did fruit count as dessert or did it have to be sugary and gooey to be a “real” dessert? Did you stop eating when you were satisfied? Were you told or encouraged to clean your plate?

School-aged children frequently prepare their own after-school snacks, which often consist of processed foods that are easy to microwave. One package might, in fact, contain two or more servings. Add a soda, and a child has had too much for a mid-day snack.

Play the video to listen to two experts from the American Academy of Pediatrics discuss childhood obesity. As you listen, you will also see candid footage of overweight children.

What advice from these experts applies to families with children of “normal” weight as well as overweight children?

1.7 The USDA Food Pyramid Begins to Emphasize Movement

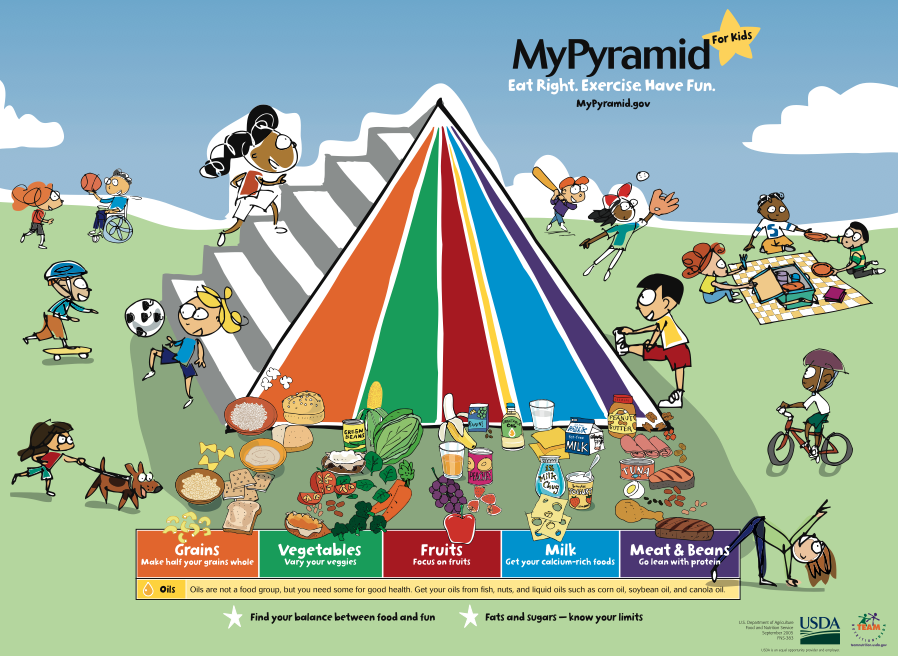

You might remember older food pyramids that were divided into sections of food with a long horizontal section at the bottom for grains and with sweets at the very top! The 2005 USDA pyramid for a healthy diet, shown here, is similar to one created earlier by Dr. Walter Willett at the Harvard School of Public Health (Willett, 2001). The important foundation of both healthful diets emphasizes exercise, not just food.

During their school years, children need approximately 2,000 calories per day. In the 2010 Dietary Guidelines, there are more recommendations that will help parents make healthy choices for their families. For example, consumers are encouraged to choose water over sugary drinks and to comparison shop when buying soups and bread so that low-sodium choices are purchased.

In 2005, the food pyramid was updated by the USDA and made a much stronger statement about the role of physical activity than had previous pyramids. The emphasis is on lifestyle and not just food.

The food group bands run from the top of the pyramid to the base. Each band is of a different width to indicate the proportion of food that should be consumed from each food group. The bands are wider at the base to remind people to eat mostly foods without solid fats and added sugar.

The stairs are a reminder that children (and everyone!) should try to incorporate as much physical activity and exercise as possible into their daily lives. Children and adolescents should spend at least 60 minutes in some sort of physical activity almost every day.

1.8 Encouraging Healthy Lifestyles

The phrase “encouraging a healthy lifestyle” means helping a child to develop habits that will promote good eating and exercise routines for years. This kind of change is not a diet or an overnight fix. So what can families do?

- Establish expectations for family physical activity, such as bike rides, hikes, long walks, or any other physical activity that the family can enjoy doing together.

- Plan meals and snacks with occasional sweets. Have favorite fruits and low-fat dips available after school. Make the sweets a now-and-then treat so that no foods are forbidden.

- Find unique ways to celebrate special achievements that do not involve food.

- Ensure that at least half of the grain products eaten are whole grains.

- Children between the ages of 2 and 8 years need two cups of milk a day, and those older than 9 years need three cups of milk a day. Low-fat or fat-free milk is encouraged.

- A variety of fruits and vegetables are important for children. Over the course of a week, children should consume all five vegetable groups, including orange vegetables, legumes, starchy vegetables, leafy greens, and others.

- The USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) does not specifically encourage protein because most children in the United States already receive an adequate amount in their diet.

Play the video to listen to Matt’s story. Given the wisdom of hindsight (as they say, it is always 20/20), what would have been a more effective response to the stress that Matt was experiencing? What do you think of Matt’s weight management method? If you think Matt’s ideas are good, which of them do you think will work? If your reaction is positive, what aspects of Matt’s regimen do you think might help others? If the ideas are not good or you have concerns, please explain what potential problems you anticipate for Matt?

1.9 Closing Thoughts: Let’s Move!

After completing this activity, it is evident that we need to move! On an individual basis, we need to get up and get moving by becoming more active. As families, we need to move toward healthy eating choices and leisure activities. In fact, “Let’s Move!” is the name of the initiative launched by First Lady Michelle Obama in February, 2010 to address the serious challenge of childhood obesity. President Obama’s Task Force on Childhood Obesity has been established to develop strategies so that by 2030 our childhood obesity rate will fall to 5%, which is about the rate of the baby-boomer generation. To reach this goal, Wojcicki & Heyman (2010) point out that the nutritional content of school lunches will have to meet higher standards and nutritional product labeling for consumers will have to be improved.

The website, http://www.letsmove.gov/, has information for kids, parents, school administrators and teachers, community leaders, and even chefs!

- Kids can download a screen time log for tracking TV and computer time and find a list of fun ideas for being active during commercial breaks.

- Moms can access a personalized MyPyramid Menu Planner to make smart meal choices when pregnant and breastfeeding based on their height, weight, and activity level.

- Let’s Move Cities and Towns provides tools for mayors to form timelines for their towns.

Hopefully, babies born in the current cohort will fulfill the dreams of “Let’s Move!”

1.10 Check Your Understanding

A 10-year-old is most likely to be concerned that his or her obesity may lead to:

The foundation level of the Harvard School of Public Health and USDA food pyramid consists of:

Overweight children eat high-fat foods in larger amounts than do leaner children.

How have evolutionary psychologists looked at the ways in which the sense of taste and fat storage have been influenced by natural selection?

1.11 Activity Completed!

Activity results are being submitted...

REFERENCES:

[Center for Disease Control] CDC Grand Rounds: Childhood Obesity in the United States. URL: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6002a2.htm?s_cid=mm6002a2_w Retrieved 3/31/11

Collins, A. & Peebles, R. (2011). Pediatric obesity: A pediatrician’s viewpoint. In Debasis Bagchi (Editor) Global Perspectives on Childhood Obesity: Current Status, Consequences and Prevention. Pages 257-264.

Cornett, R. E. (2011). The emotional impact of obesity on children. In Debasis Bagchi (Editor) Global Perspectives on Childhood Obesity: Current Status, Consequences and Prevention. Pages 257-264.

Dalton, S. (2004). Our overweight children: What parents, schools, and communities can do to control the fatness epidemic. Berkeley: University of California Press.

[Harvard School of Public Health.] Food Pyramids: What Should You Eat? URL: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu /nutritionsource/pyramids.html Retrieved on February 24, 2011

[Mayo Clinic Staff] Childhood Obesity: Complications. URL: http://www.mayoclinic.com Retrieved 2/20/2011

Mullen, M. C., & Shield, J. (2004). Childhood and adolescent overweight: The health professional’s guide to identification, treatment, and prevention. Chicago: American Dietetic Association.

Ogden, C. L. & Flegal, K. M. (June 25, 2010). Changes in terminology for childhood overweight and obesity. National health statistics reports; no 25. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Rimm, S., & Rimm, R. (2004). Rescuing the emotional lives of overweight children: What our kids go through and how we can help. Emmaus, PA: Rodale.

Rolland-Cachera, M. G., & Bellisle, F. (2002). Nutrition. In W. Burniat, T. J. Cole, I. Lissau, & E. M. E. Poskitt (Eds.), Child and adolescent obesity: Causes and consequences, prevention and management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

U.S. Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition and Promotion. Retrieved February 24, 2011, from http://www.mypyramid.gov

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Training module for Overweight Children and Adolescents: Screen, Assess and Manage. Retrieved April, 2005, from http://www.cdc.gov/ncccdphp/dnpa/ growthcharts/training/modules/module3/text/page1a.htm

Willett, W. C., & Skerret, P. J. (2001). Eat, Drink, and be healthy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Wojcicki, J. M. & Heyman, M. B. (2010). Let’s move – Childhood obesity prevention from pregnancy and infancy onward. The New England Journal of Medicine, 362, 1457.