Challenges for Caregivers

We have seen that young children’s emotions and actions are affected by many factors, including brain maturation, culture, and peers. Now we focus on another primary influence on young children: their caregivers. Parents are crucial, and alternate caregivers become pivotal as well.

Caregiving Styles

Many researchers have studied the effects of parenting strategies and emotions. Of course, genes and cultures differ, and that shapes children. Beyond that, however, some parental practices lead to psychopathology while others encourage children to become outgoing, caring adults (Deater-

Baumrind’s Three Styles of Caregiving

Although thousands of researchers have traced the effects of parenting on child development, the work of one person, 50 years ago, continues to be influential. In her original research, Diana Baumrind (1967, 1971) studied 100 preschool children, all from California, almost all middle-

Baumrind found that parents differed on four important dimensions:

Expressions of warmth. Some parents are warm and affectionate; others, cold and critical.

Strategies for discipline. Parents vary in how they explain, criticize, persuade, and punish.

Communication. Some parents listen patiently; others demand silence.

Expectations for maturity. Parents vary in expectations for responsibility and self-

control.

Especially for Political Scientists Many observers contend that children learn their political attitudes at home, from the way their parents teach them. Is this true?

There are many parenting styles, and it is difficult to determine each one’s impact on children’s personalities. At this point, attempts to connect early child rearing with later political outlook are speculative.

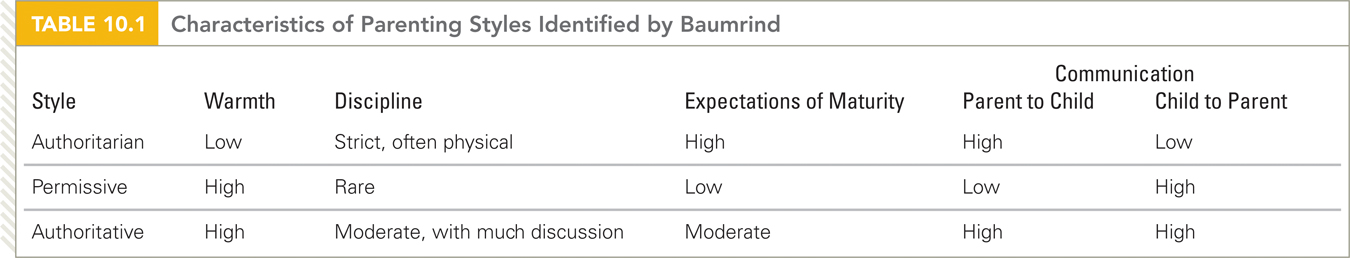

On the basis of these dimensions, Baumrind identified three parenting styles (summarized in Table 10.1).

OBSERVATION QUIZ Is the father below authoritarian, authoritative, or permissive?

It is impossible to be certain based on one moment, but the best guess is authoritative. He seems patient and protective, providing comfort and guidance, neither forcing (authoritarian) nor letting the child do whatever he wants (permissive).

Authoritarian parenting. The authoritarian parent’s word is law, not to be questioned. Misconduct brings strict punishment, usually physical. Authoritarian parents set down clear rules and hold high standards. They do not expect children to offer opinions; discussion about emotions is especially rare. (One adult from such a family said that “How do you feel?” had only two possible answers: “Fine” and “Tired.”) Authoritarian parents seem cold, rarely showing affection.

Permissive parenting. Permissive parents (also called indulgent) make few demands, hiding any impatience they feel. Discipline is lax, partly because they have low expectations for maturity. Permissive parents are nurturing and accepting, listening to whatever their offspring say, even if it is profanity or criticism of the parent.

Protect Me From the Water Buffalo These two are at the Carabao Kneeling Festival. In rural Philippines, hundreds of these large but docile animals kneel on the steps of the church, part of a day of gratitude for the harvest.

Protect Me From the Water Buffalo These two are at the Carabao Kneeling Festival. In rural Philippines, hundreds of these large but docile animals kneel on the steps of the church, part of a day of gratitude for the harvest.Authoritative parenting. Authoritative parents set limits, but they are flexible. They encourage maturity, but they usually listen and forgive (not punish) if the child falls short. They consider themselves guides, not authorities (unlike authoritarian parents) and not friends (unlike permissive parents).

Other researchers describe a fourth style, called neglectful/uninvolved parenting, which may be confused with permissive but is quite different. The similarity is that neither permissive nor neglectful parents use physical punishment. However, neglectful parents are oblivious to their children’s behavior; they seem not to care. By contrast, permissive parents care very much: They defend their children, arrange play dates, and sacrifice to buy coveted toys.

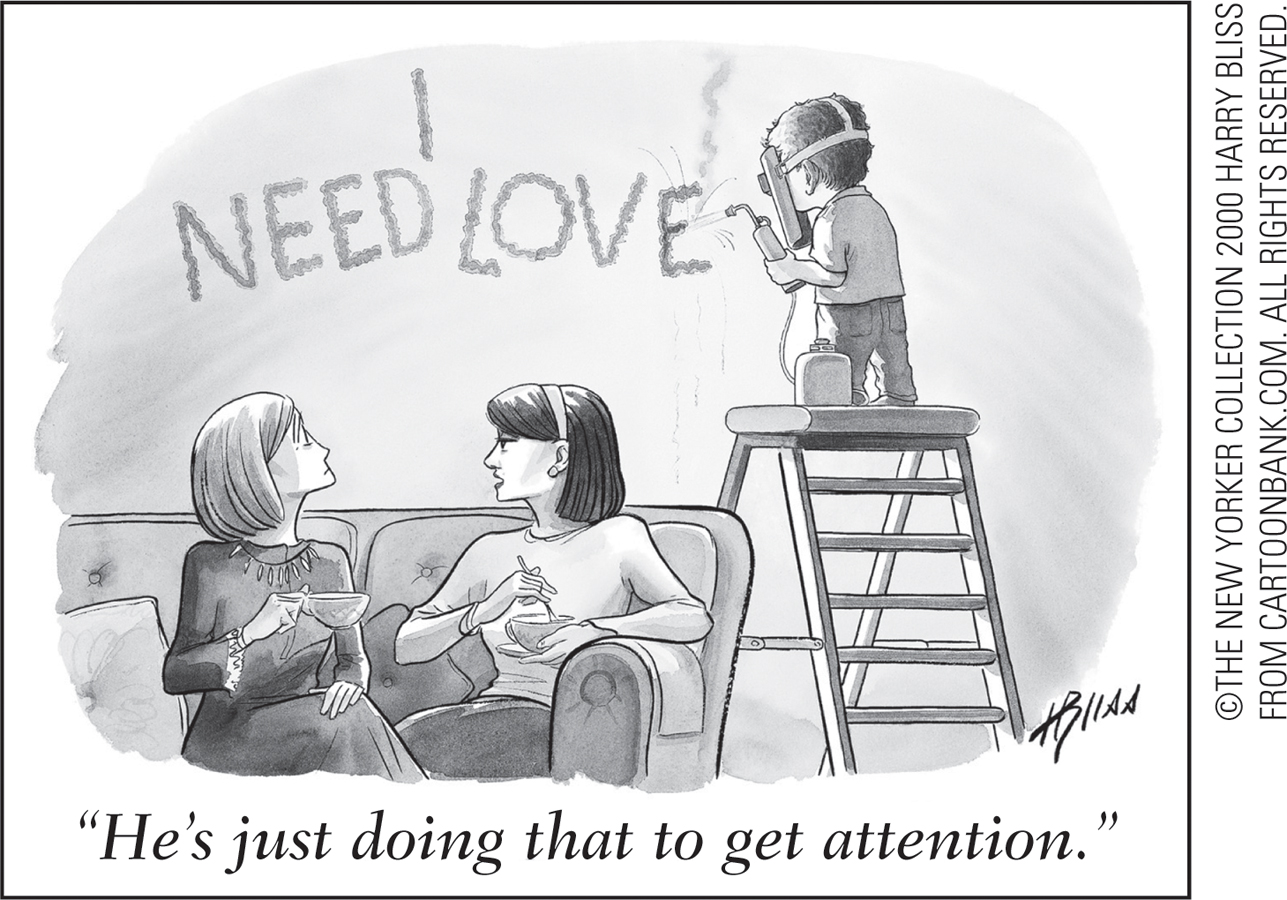

The following long-

Authoritarian parents raise children who become conscientious, obedient, and quiet but not especially happy. Such children tend to feel guilty or depressed, internalizing their frustrations and blaming themselves when things don’t go well. As adolescents, they sometimes rebel, leaving home before age 20.

Permissive parents raise children who lack self-

control, especially in the give- and- take of peer relationships. Inadequate emotional regulation makes them immature and impedes friendships, so they are unhappy. They tend to continue to live at home, still dependent on their parents, in early adulthood. Authoritative parents raise children who are successful, articulate, happy with themselves, and generous with others. These children are usually liked by teachers and peers, especially in cultures that value individual initiative (e.g., the United States).

Neglectful/uninvolved parents raise children who are immature, sad, lonely, and at risk of injury and abuse, not only in early childhood but also lifelong.

Problems with Baumrind’s Styles

Baumrind’s classification schema is often criticized. Problems include the following:

Her participants were not diverse in SES, ethnicity, or culture.

She focused more on adult attitudes than on adult actions.

She overlooked children’s temperamental differences.

She did not recognize that some “authoritarian” parents are also affectionate.

She did not realize that some “permissive” parents provide extensive verbal guidance.

We now know that a child’s temperament powerfully affects caregivers. Caring for a child is an interactive process, and good caregivers treat each child as an individual who needs personalized care. That may make outsiders misinterpret the parental practices they see.

For example, fearful children require reassurance while impulsive ones need strong guidelines. Parents of such children may, to outsiders, seem permissive or authoritarian. Of course, some parents are too lax or too rigid, but every child needs some protection and guidance; Some more than others. Overprotection and hypervigilance are both a cause and consequence of childhood anxiety (McShane & Hastings, 2009; Deater-

Cultural Variations

The significance of context is obvious when children of various ethnic groups are compared because parents in various cultures have heartfelt, and sometimes opposite, child-

U.S. parents of Chinese, Caribbean, or African heritage are often stricter than those of European backgrounds, yet their children seem to develop better than if their parents were easygoing (Parke & Buriel, 2006; Ng et al., 2014). Latino parents are sometimes thought to be too intrusive, other times too permissive—

Does culture erase the effects of each of the four styles of parenting? No. However, the outcome of any parenting style is affected by the child’s temperament, the parent’s personality, and the social context. This later factor may be particularly important for minority children growing up in a majority culture (Henry, 2011).

In a detailed study of 1,477 instances in which Mexican American mothers of 4-

Almost never, however, did the mothers use physical punishment or even harsh threats when the children did not immediately do as they were told—

Hailey [the 4-

[Livas-

Note that the mother’s first three efforts failed, and then a look accompanied by an explanation (albeit inaccurate in that setting, as no one could be hurt) succeeded. The researchers explain that these Mexican American families did not fit any of Baumrind’s categories; respect for adult authority did not mean a cold mother–

Warmth and caring may be the crucial aspect of parenting style in every ethnic group. Other research also finds that parental affection and warmth allow children to develop self-

Given a multicultural and multicontextual perspective, developmentalists hesitate to be too specific in recommending any particular parenting style. That does not mean that all families function equally well—

Becoming Boys or Girls: Sex and Gender

Biology determines whether a baby is male or female except in very rare cases when genes do not function normally. As you remember from Chapter 4, at about 8 weeks after conception, the SRY gene directs growth of external reproductive organs, and then male hormones exert subtle control over the brain, body, and later behavior. Without that gene, the fetus develops female organs, which produce female hormones that also affect the brain and behavior.

Sometimes the sex hormones are inactive prenatally and the child does not develop like the typical boy or girl (Hines, 2013). That is rare; most children are male or female in all three ways: chromosomes, genitals, and hormones. That is their nature, but obviously nurture affects sexual development lifelong.

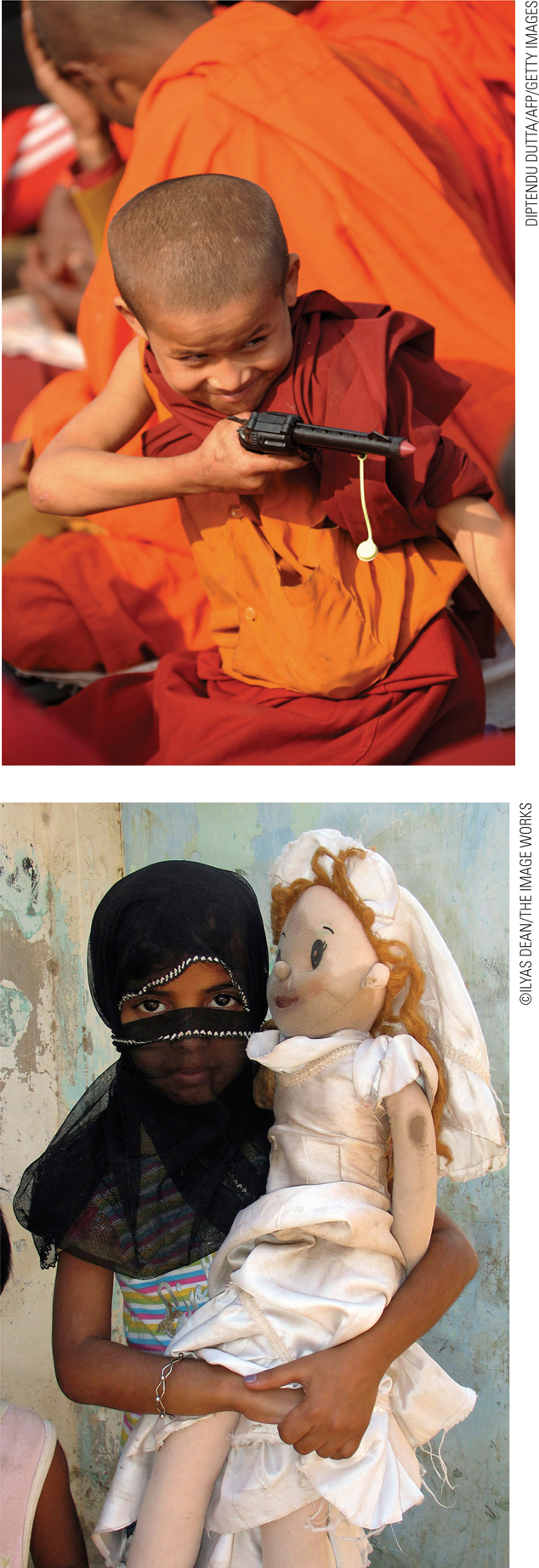

During early childhood, patterns of behavior and preferences related to gender become important to children and apparent to adults. Before age 2, children apply gender labels (Mrs., Mr., lady, man) consistently. By age 4, children are convinced that certain toys (such as dolls or trucks) and roles (not just Daddy or Mommy, but also nurse, teacher, police officer, soldier) are “best suited” for one sex or the other.

Sexual stereotypes often become obvious and rigid between ages 3 and 6. Dynamic-

Many scientists distinguish sex differences, which are biological differences between males and females, from gender differences, which are culturally prescribed roles and behaviors. In theory, this distinction seems straightforward, but, as with every nature–

Young children are often confused about the origin of male-

Many preschool children do not realize that their own biological sex is permanent. In one preschool, the children themselves decided that one wash-

Boy: This is for the boys.

Girl:

Stop it. I’m not a girl and a boy, so I’m here.

Boy:

What?

Girl:

I’m a boy and also a girl.

Boy:

You, now, are you today a boy?

Girl:

Yes.

Boy:

And tomorrow what will you be?

Girl:

A girl. Tomorrow I’ll be a girl. Today I’ll be a boy.

Boy:

And after tomorrow?

Girl:

I’ll be a girl.

[Ehrlich & Blum-

As already mentioned, girls tend to play with other girls and boys with other boys. Despite their parents’ and teachers’ wishes, children say, “No girls [or boys] allowed.” Most older children consider ethnic discrimination immoral, but they accept some sex discrimination (Møller & Tenenbaum, 2011). Why?

Theories of Gender Development

A dynamic-

Psychoanalytic Theory

Freud (1938/1995) called the period from about ages 3 to 6 the phallic stage, named after the phallus, the Greek word for penis. At about 3 or 4 years of age, said Freud, boys become aware of their male sexual organ. They masturbate, fear castration, and develop sexual feelings toward their mother.

These feelings make every young boy jealous of his father—

Freud believed that this ancient story dramatizes the overwhelming emotions that all boys feel about their parents—

That marks the beginning of morality, according to psychoanalytic theory. This theory contends that a boy’s fascination with superheroes, guns, kung fu, and the like arises from his unconscious impulse to kill his father. Further, an adult man’s homosexuality, homophobia, or obsession with guns, prostitutes, and hell arise from problems at the phallic stage.

Freud offered several descriptions of the moral development of girls. One centers on the Electra complex (also named after a figure in classical mythology). The Electra complex is similar to the Oedipus complex in that the little girl wants to eliminate the same-

According to psychoanalytic theory, at the phallic stage, children cope with guilt and fear through identification that is, they try to become like the same-

Most psychologists have rejected Freud’s theory regarding sex and gender. They favor one or another of many other theories to explain the young child’s sex and gender awareness.

a case to study

My Daughters

Since the superego arises from the phallic stage, and since Freud believed that sexual identity and expression are crucial for mental health, his theory suggests that parents should encourage children to accept and follow gender roles. Many social scientists disagree. They contend that the psychoanalytic explanation of sexual and moral development “flies in the face of sociological and historical evidence” (David et al., 2004, p. 139).

Accordingly, I learned in graduate school that Freud was unscientific, and I deliberately dressed my baby girls in blue, not pink. However, as explained in Chapter 2, developmental scientists seek to connect research, theory, and experience. My own experience has made me rethink my rejection of Freud, as episodes with my four daughters illustrate.

My rethinking began with a conversation with my eldest daughter, Bethany, when she was about 4 years old:

Bethany:

When I grow up, I’m going to marry Daddy.

Me:

But Daddy’s married to me.

Bethany:

That’s all right. When I grow up, you’ll probably be dead.

Me:

[Determined to stick up for myself] Daddy’s older than me, so when I’m dead, he’ll probably be dead, too.

Bethany:

That’s OK. I’ll marry him when he gets born again.

I was dumbfounded, without a good reply. I had no idea where she had gotten the concept of reincarnation. Bethany saw my face fall, and she took pity on me:

Bethany:

Don’t worry, Mommy. After you get born again, you can be our baby.

The second episode was a conversation I had with my daughter Rachel when she was about 5:

Rachel:

When I get married, I’m going to marry Daddy.

Me:

Daddy’s already married to me.

Rachel:

[With the joy of having discovered a wonderful solution] Then we can have a double wedding!

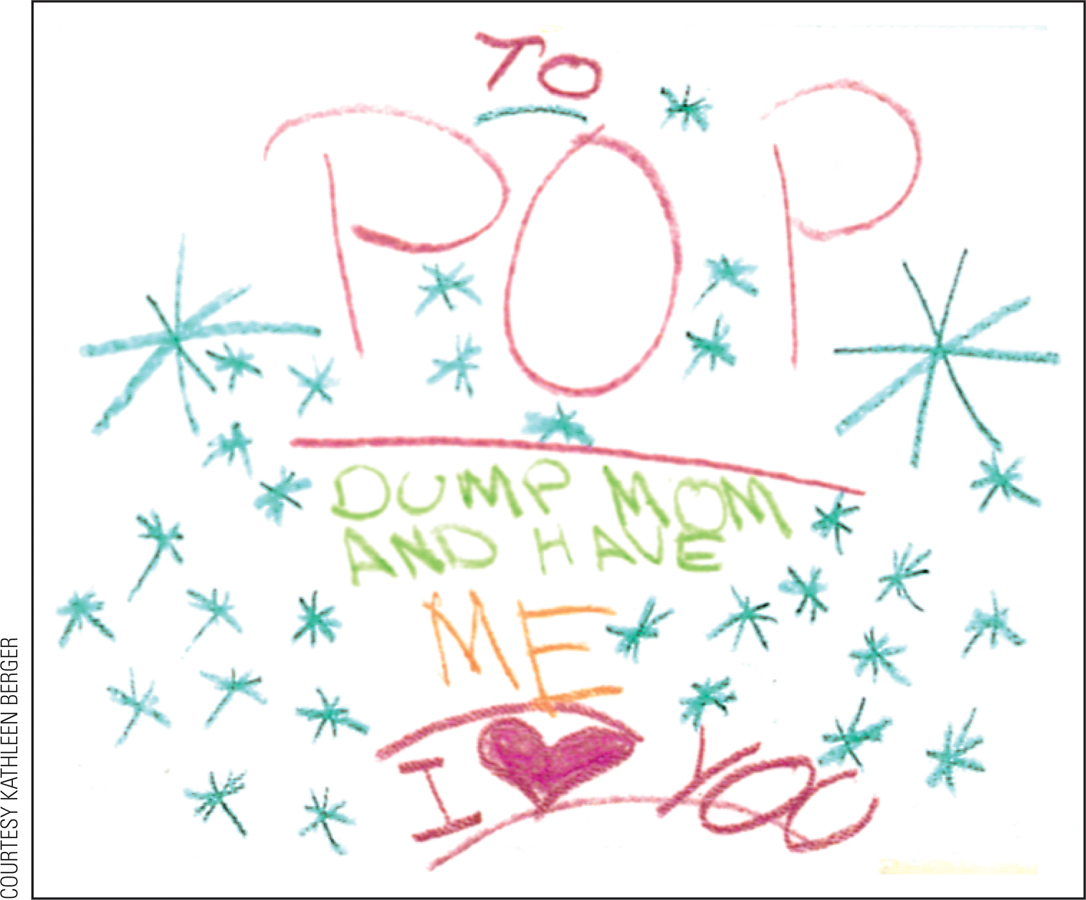

The third episode was considerably more graphic. It took the form of a “valentine” left on my husband’s pillow on February 14th by my daughter Elissa (see Figure 10.2).

Finally, when Sarah turned 5, she also said she would marry her father. I told her she couldn’t, because he was married to me. Her response revealed one more hazard of watching TV: “Oh, yes, a man can have two wives. I saw it on television.”

As you remember from Chapter 1, a single example (or four daughters from one family) does not prove that Freud was correct. I still think Freud was wrong on many counts. But his description of the phallic stage seems less bizarre than I once thought.

Pillow Talk Elissa placed this artwork on my husband’s pillow. My pillow, beside it, had a less colorful, less elaborate note—

Behaviorism

Behaviorists believe that virtually all roles, values, and morals are learned. To behaviorists, gender distinctions are the product of ongoing reinforcement and punishment, as well as social learning. Parents, peers, and teachers all reward behavior that is “gender appropriate” more than behavior that is “gender inappropriate” (Berenbaum et al., 2008).

For example, “adults compliment a girl when she wears a dress but not when she wears pants” (Ruble et al., 2006, p. 897), and a boy who asks for both a train and a doll for his birthday is likely to get the train. Boys are rewarded for boyish requests, not for girlish ones. Indeed, the parental push toward traditional gender behavior in play and chores is among the most robust findings of decades of research on this topic (Eagly & Wood, 2013).

Social learning is considered an extension of behaviorism. According to that theory, people model themselves after people they perceive to be nurturing, powerful, and yet similar to themselves. For young children, those people are usually their parents.

As it happens, adults are the most sex-

Furthermore, although national policies (e.g., subsidizing preschool) impact gender roles and many fathers are involved caregivers, women in every nation do much more child care, house cleaning, and meal preparation than do men (Hook, 2010). Children follow those examples, unaware that the behavior they see is caused partly by their very existence: Before children are born, many couples share domestic work, but baby care often changes that.

Cognitive Theory

Cognitive theory offers an alternative explanation for the strong gender identity that becomes apparent at about age 5 (Kohlberg et al., 1983). Remember that cognitive theorists focus on how children understand various ideas. A gender schema is the child’s understanding of male–

Cognitive theorists point out that young children have many gender-

As Piaget noted, during the preoperational stage, appearance trumps logic. One group of researchers who advocate the cognitive interpretation noted that “[m]any young children pass through a stage of gender appearance rigidity; girls insist on wearing dresses, often pink and frilly, whereas boys refuse to wear anything with a hint of femininity” (Halim et al., 2014, p. 1091). In the research reported by this group, parents sometimes were quite unisex, in attitude or action, but that did not necessarily sway a preschool girl who wanted a bright pink tutu and a sparkly tiara. The child’s gender schema overcame the child’s experience.

Sociocultural Theory

Sociocultural theory stresses the importance of cultural values and customs. Some aspects of a culture are transmitted through the parents, as explained in the discussion of behaviorism, but many more arise from the larger community. This varies from place to place and time to time, as would be expected for any cultural value.

Consider a meta-

Thus, national culture affects even personal adult choices such as marriage partners. Children are influenced by norms. That is why boys want to be soldiers, or engineers, or football players—

My 4-

Universal Theories

Humanism stresses the hierarchy of needs, beginning with survival, then safety, then love and belonging. The final two needs—

Ideally, babies have all their basic needs met, and toddlers learn to feel safe, which makes love and belonging crucial during early childhood. Children increasingly strive for admiration from their peers. Therefore, the girls seek to be one of the girls and the boys to be one of the boys.

In a study of slightly older children, participants wanted to be part of same-

On her first day of school, Mia sits at the lunch table eating a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. She notices that a few boys are eating peanut butter and jelly, but not one girl is. When her father picks her up from school, Mia runs up to him and exclaims, “Peanut butter and jelly is for boys! I want a turkey sandwich tomorrow.”

[Quoted in Miller et al., 2013, p. 307]

Humanism would interpret this as evidence that Mia’s need to belong to the girls in her class overruled her earlier basic need, which was satisfied with peanut butter and jelly.

Evolutionary theory holds that male–

According to evolutionary theory, the species’ need to reproduce is part of everyone’s genetic heritage, which makes young boys and girls copy adult behavior that is sexually alluring. For example, one 6-

Thus, according to this theory, over millennia of human history, genes, chromosomes, and hormones have evolved to allow the species to survive. Genes dictate that boys are more active (rough-

What Is Best?

Each of the major developmental theories strives to explain the ideas that young children express and the roles they follow. No consensus has been reached. Regarding sex or gender, those who contend that nature is more important than nurture, or that nurture is more important than nature, tend to design, cite, and believe studies that endorse their perspective. Only recently has a true interactionist perspective (that is a perspective that emphasizes that nature affects nurture and vice versa) on gender been endorsed (Eagly & Wood, 2013).

Video Activity: The Boy Who Was a Girl presents the case of David/Brenda Reimer as an exploration of what it means to be a boy or a girl.

These theories raise important questions: What roles should parents and other caregivers teach? Should every child learn to combine the best of both sexes (called androgyny), thereby causing gender stereotypes to crumble as children become more mature, much as a belief in Santa and the Tooth Fairy disappears? Or should male–

Answers vary among developmentalists as well as among parents and cultures. Generally, children become more stereotyped in the gender behaviors they endorse, a tendency some adults encourage and others do not. A few children rebel. They are called transgender, or gender dysphoric, or non-

Determining how to raise children who are happy to be themselves but not prejudiced against those of the other sex or against those who are gender non-

SUMMING UP Caregiving styles vary, ranging from very strict, cold, and demanding to very lax, warm, and permissive. Baumrind’s classic research categorized parenting as authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive; these categories still seem relevant, even though the original research was limited in many ways. A fourth type, neglectful/uninvolved, has also been described. Cross-

The young child’s ideas and stereotypes about males and females are quite rigid during early childhood. Norms are changing. Theorists differ in their explanations and interpretations of gender differences, some emphasizing biological and brain differences, others stressing the impact of culture. That is true for caregivers as well: All are affected by their culture and assumptions, but some believe that the primary impetus for boy–

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 10.13

Which parenting style seems to promote the happiest, most successful children?

Authoritative parents produce the happiest, most successful children. These parents set limits, but they are flexible. They encourage maturity, but they usually listen and give consequences if the child falls short. They consider themselves guides, not authorities and not friends.Question 10.14

Why do U.S. childhood professionals advise limitations on electronic media for young children?

The problem with media is that violent media teaches aggression and even nonviolent media takes time from constructive interaction and creative play. Social interaction among family members is also reduced when a TV is on, whether or not anyone is watching.Question 10.15

What did Freud believe about the attitudes young children have regarding their mothers and fathers?

According to Freud's psychoanalytic theory, at the phallic stage children cope with guilt and fear through identification; that is, they try to become like the same–sex parent. Consequently, young boys copy their fathers' mannerisms, opinions, actions, and girls copy their mothers'. Both boys and girls exaggerate the male or female role. Question 10.16

What do behaviorists say about the origins of gender roles?

Behaviorists believe that all roles are learned through ongoing reinforcement, punishment, and social learning (or modeling). They suggest that authority figures reward gender–appropriate behavior and that children model themselves after the adults who care for them. Question 10.17

How is the idea of the sexes as opposites related to cognitive theory?

Cognitive theorists point out that young children have many gender–related experiences but not much cognitive depth. They see the world in simple, egocentric terms. For this reason, their gender schemas categorize male and female as opposites. Nuances, complexities, exceptions, and gradations about gender (as well as just about everything else) are beyond them. Question 10.18

How does evolutionary theory explain why children follow gender norms?

Evolutionary theory holds that sexual attraction is crucial for humankind's survival, as it underlies the desire to reproduce. For this reason, males and females try to look attractive to the other sex by walking, talking, and laughing in gendered ways. If girls see their mothers wearing make–up and high heels, they want to do likewise. According to evolutionary theory, the species' need to reproduce is part of everyone's genetic heritage, so young boys and girls practice becoming attractive to the other sex. This behavior ensures that they will be ready after puberty to find each other and that a new generation will be born, as evolution requires. Question 10.19

Why is the nature–

nurture debate likely to arise when gender roles are considered? Theorists differ in their explanations and interpretations of gender differences, some emphasizing biological and brain differences (nature), others stressing the impact of culture (nurture). That is true for caregivers as well: All are affected by their culture and assumptions, but some believe that the primary impetus for boy–girl behavior is biological, others that culture is far more influential.