Health Problems in Middle Childhood

Some chronic health conditions, including Tourette syndrome, stuttering, and allergies, often worsen during the school years. Even minor problems—

Researchers increasingly recognize “that the expression and outcome for any problem will depend on the configuration and timing of a host of surrounding circumstances” (Hayden & Mash, 2014, p. 49). Parents and children are not merely reactive: In a dynamic-

Childhood Obesity

Body mass index (BMI) is a measure of body fat that depends on how heavy a person is at their height. Childhood overweight is usually defined as a BMI above the 85th percentile, and childhood obesity is defined as a BMI above the 95th percentile for children at a particular age. In 2012, 18 percent of 6-

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

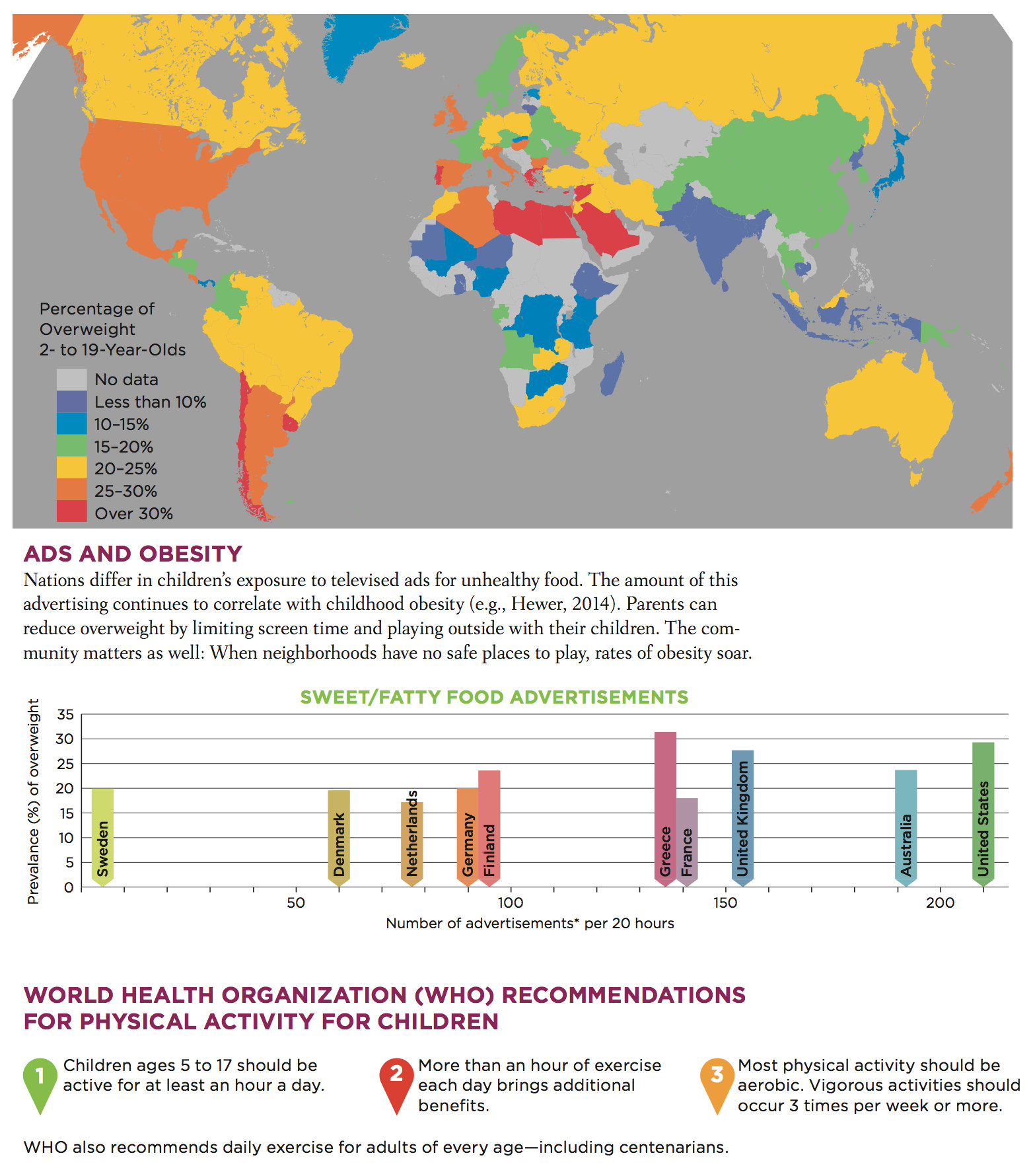

Childhood Obesity Around the Globe

Obesity now causes more deaths worldwide than malnutrition. Reductions are possible. A multi-faceted prevention effort—including mothers, preschools, pediatricians, grocery stores, and even the White House—has reduced obesity in the United States for 2- to 5-year-olds. It was 13.9 percent in 2002 and was 8.4 percent in 2012. However, obesity rates from age 6 to 60 remain high everywhere.

Especially for Teachers A child in your class is overweight, but you are hesitant to say anything to the parents, who are also overweight, because you do not want to offend them. What should you do?

Speak to the parents, not accusingly (because you know that genes and culture have a major influence on body weight) but helpfully. Alert them to the potential social and health problems their child’s weight poses. Most parents are very concerned about their child’s well-

Childhood obesity is increasing worldwide, having more than doubled since 1980 in all three nations of North America (Mexico, the United States, and Canada) (Ogden et al., 2011). Since 2000, rates seem to have leveled off in the United States and have actually declined in preschool children, but for older children, they continue to increase in most nations, including the most populous two, China and India (Gupta et al., 2012; Ji et al., 2013) (see Visualizing Development, p. 352).

Childhood overweight correlates with asthma, high blood pressure, and elevated cholesterol (especially LDL, the “lousy” cholesterol). As excessive weight builds, average school achievement decreases, self-

Especially for Parents Suppose that you always serve dinner with the television on, tuned to a news broadcast. Your hope is that your children will learn about the world as they eat. Can this practice be harmful?

Habitual TV watching correlates with obesity, so you may be damaging your children’s health rather than improving their intellect. Your children would probably profit more if you were to make dinner a time for family conversation about world events.

a view from science

What Causes Childhood Obesity?

There are “hundreds if not thousands of contributing factors” for childhood obesity, from the cells of the body to the norms of the society (Harrison et al., 2011, p. 51). Dozens of genes affect weight by influencing activity level, hunger, food preferences, body type, and metabolism. New genes and alleles that affect obesity—

Knowing that genes are involved may slow down the impulse to blame people for being overweight. However, genes cannot explain why obesity rates have increased dramatically, since genes change little from one generation to the next (Harrison et al., 2011). Instead, cohort changes must be responsible.

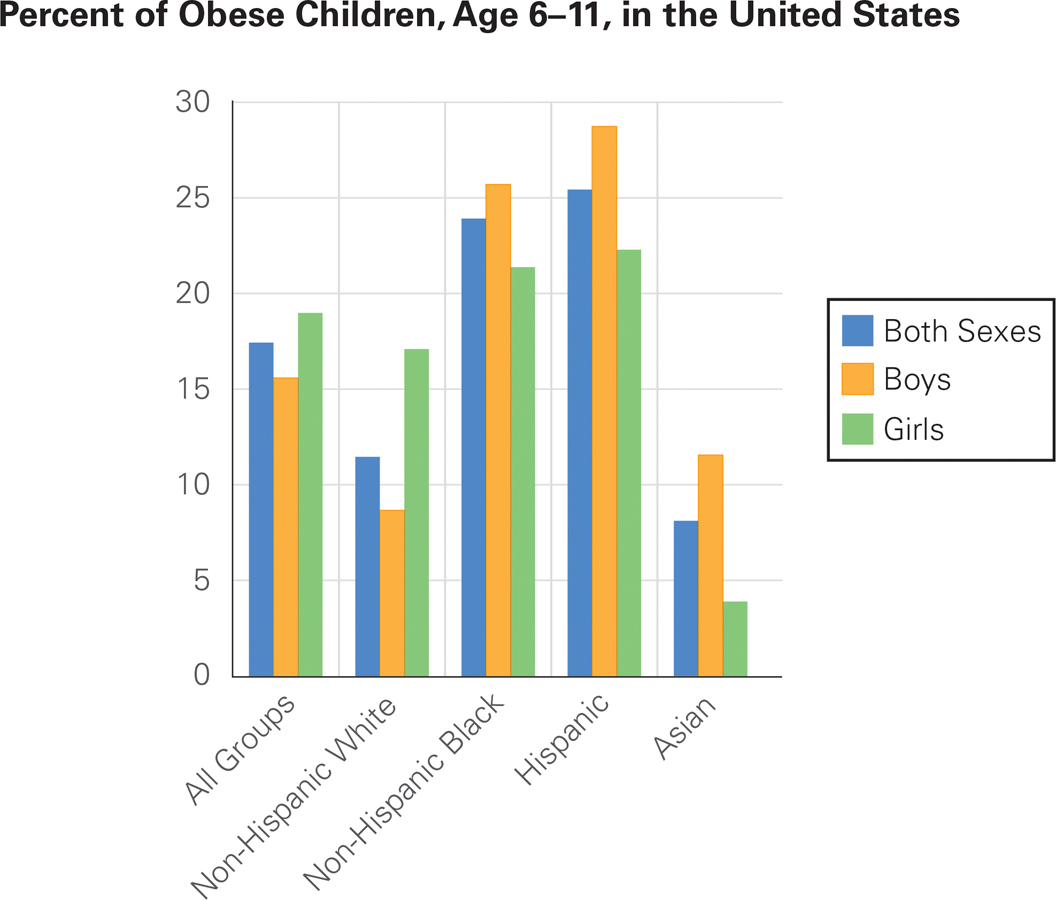

Look at the figure on obesity among 6-

Fatter and Fatter The incidence of obesity (defined here as a BMI above the 95th percentile, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts) increases with age. Infants and preschoolers have lower rates than schoolchildren, which suggests that nurture is more influential than nature.

At first glance, one might think that the large ethnic gaps (such as 9 percent of Asian Americans and 26 percent of Hispanic Americans) might be genetic. But consider gender: Non-

What parenting practices make children too heavy? Obesity rates rise if: infants are not breast-

Although family habits in infancy and early childhood can set a child on the path to obesity, during middle childhood, children themselves have pester power—the ability to get adults to do what they want (Powell et al., 2011). Often they pester their parents to buy calorie-

On average, family contexts changed for the worse toward the end of the twentieth century in North America and are spreading worldwide. For instance, family size has decreased, and as a result, pester power has increased, and more food is available for each child. That makes childhood obesity collateral damage from reduction of birth rate—

Attempts to limit sugar and fat clash with the goals of many corporations, since snacks and processed foods are very profitable. On the plus side, many schools have policies that foster good nutrition. A national survey in the United States found that schools are reducing all types of commercial food advertising. However, vending machines are still prevalent in high schools, and free food coupons are often used as incentives in elementary schools (Terry-

Overall, simply offering healthy food is not enough to convince children to change their diet; context and culture are crucial (Hanks et al., 2013). Communities can build parks, bike paths, and sidewalks, and nations can decrease subsidies for sugar and corn oil and syrup. As educators try to improve children’s eating habits, cultural sensitivity is crucial, since each ethnic group has preferred foods and family patterns. To work against culture is foolish, but working within cultures can protect the children.

For example, African American parents may consider fried fish and potatos part of their culture, but so are baked fish and a variety of greens; Mexican American parents may enjoy rice and beans, but those can be cooked without added fat. Immigrants who want to “eat American” may not be aware of the correlation between fast food and childhood obesity (Alviola et al., 2013).

Home cooking is usually better. In the United States, older adults who immigrated after childhood have lower rates of obesity than do the native born, yet their children are more often obese than other children, a statistic that should give everyone pause.

Rather than trying to zero in on any single factor, a dynamic-

Asthma

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways that makes breathing difficult. Sufferers have periodic attacks, sometimes requiring a rush to the hospital emergency room, a frightening experience for children who know that asthma might kill them (although it almost never does in childhood).

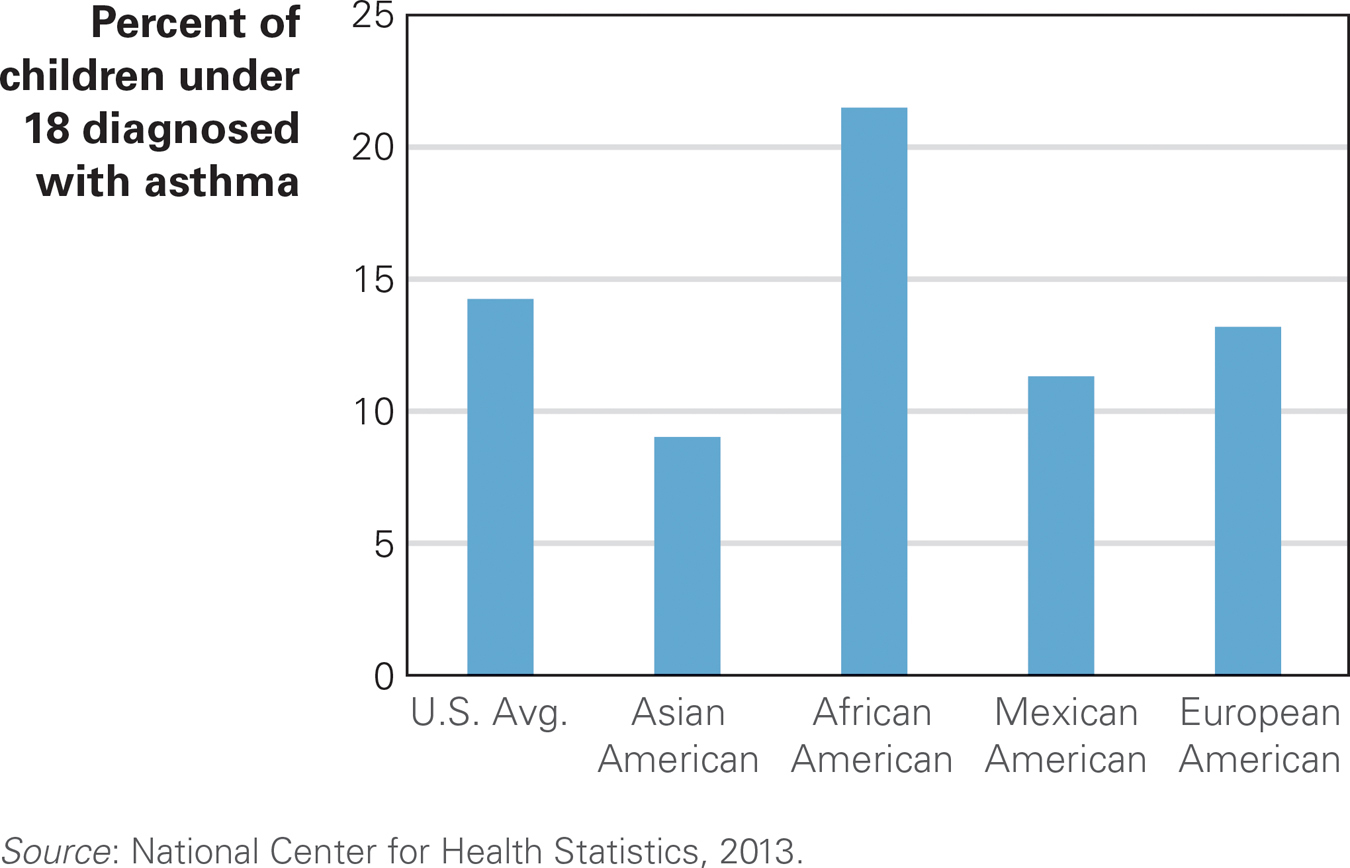

In the United States, childhood asthma rates have tripled since 1980. (See Figure 11.2 for current rates for those younger than 18 years old.) Parents report that 14 percent of U.S. 5-

Not Breathing Easy Of all U.S. children younger than 18, 14 percent have been diagnosed at least once with asthma. Why are Puerto Rican and African American children more likely to have asthma? Does the answer have to do with nature or nurture, genetics, or pollution?

Researchers have long sought the causes of asthma. A few alleles have been identified as contributing factors, but none acts in isolation. Several aspects of modern life—

Some experts suggest a hygiene hypothesis: that “the immune system needs to tangle with microbes when we are young” (Leslie, 2012, p. 1428). Children may be overprotected from viruses and bacteria. In their concern about hygiene, parents prevent exposure to minor infections, diseases, and family pets that would strengthen their child’s immunity. This hypothesis is supported by data showing that (1) first-

None of these factors, however, proves the hygiene hypothesis. Perhaps farm children are protected by drinking unpasteurized milk, by outdoor chores, or by alleles that are more common in farm families, rather than by exposure to a range of bacteria (von Mutius & Vercelli, 2010). In fact, there are “many paths to asthma,” with no one cause identified as the crucial one (H. Kim et al., 2010). One review of the hygiene hypothesis notes “the picture can be dishearteningly complex” (Couzin-

However, there is hope. Consider a study of 133 Latino adult smokers, all caregivers of children with asthma. They agreed to allow a Spanish-

Three months later, one-

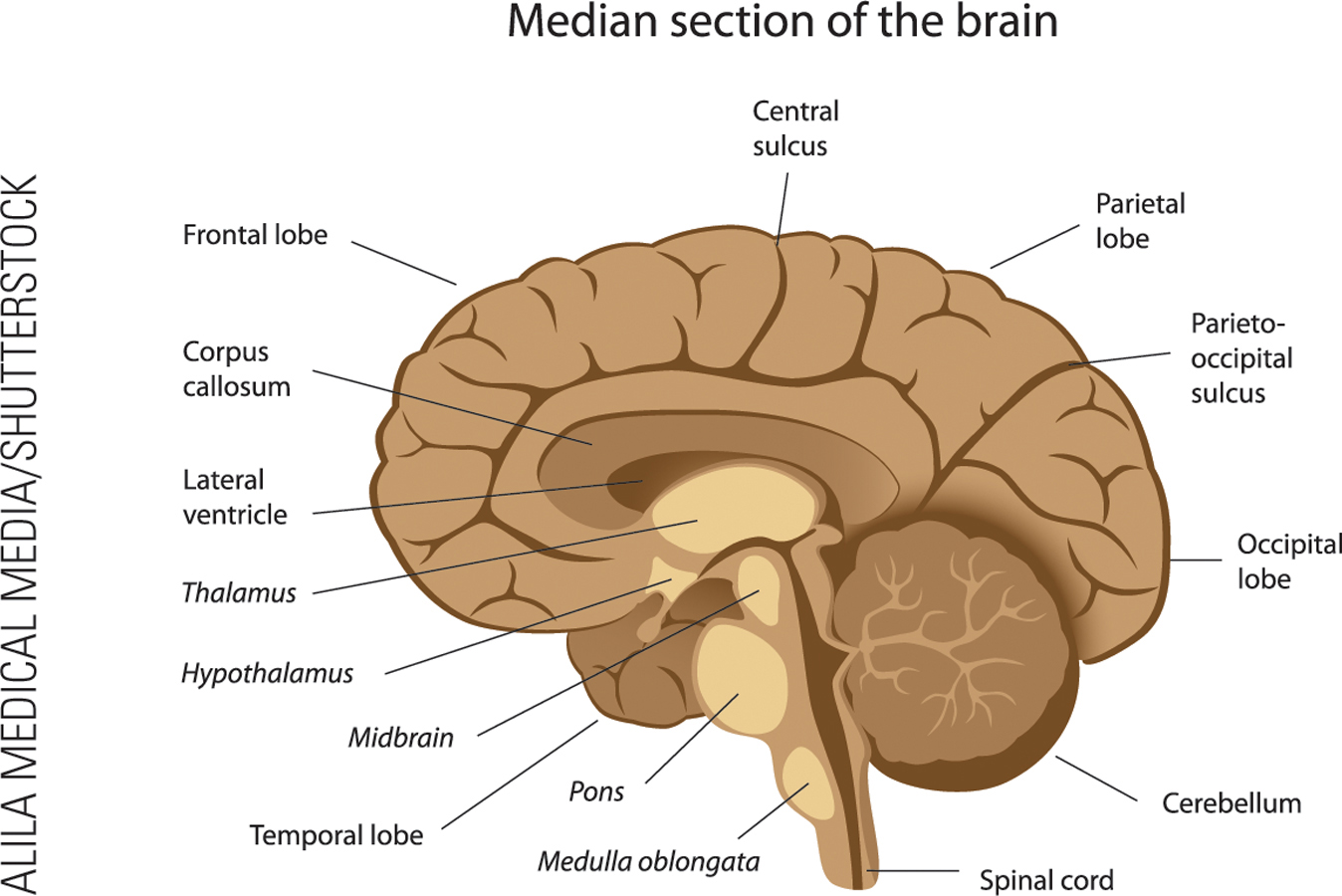

Video Activity: Brain Development: Middle Childhood depicts the changes that occur in a child’s brain from age 6 to age 11.

SUMMING UP Some children have chronic health problems that interfere with school and friendship. Among these are obesity and asthma, both of which are increasing in every nation and have genetic and environmental causes. Childhood obesity may seem harmless, but it leads to social problems among classmates and severe health problems later on. Asthma’s harm is more immediate: Children with asthma often miss school and may be rushed to emergency rooms, gasping for air. Although genes predispose some children to each particular health problem, family practices and neighborhood context can increase rates of obesity and asthma, and many society-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 11.5

What are the national and cohort differences in childhood obesity?

Childhood obesity is increasing worldwide, and it has more than doubled since 1980 in all three nations of North America. Peru, Portugal, Spain, and Greece reported the highest rates of childhood obesity, with more than 30% of their 5–to 17– year– olds considered overweight in 2012. In the United States, Canada, and Mexico in 2012, approximately 25% to 30% of that age group was overweight, and similar rates were seen in the UK, Italy, Egypt, and Chile. The rates were slightly lower (20% to 25%) in Australia, Brazil, Iceland, Finland, Germany, and Hungary. In South Africa, Argentina, Venezuela, France, Poland, Turkey, Pakistan, Thailand, South Korea, and Japan, the rates are between 15% and 20%. Greenland, Sweden, Estonia, and Iraq have rates of 10% to 15%, and Russia and China have less than 10%. Question 11.6

Why does a thin 6-

year- old not need to “fatten up”? Children grow at their own pace, and their weight and metabolism are governed by some 200 genes. A thin 6–year– old may well turn into a 12– year– old of normal weight. The lowest rates of obesity are among 2– to 5– year– olds, and obesity increases as children grow older. Children do not need to try to speed up that process. Question 11.7

What roles do nature and nurture play in childhood asthma?

A few alleles (which support nature) have been identified as contributing factors to childhood asthma, but none acts in isolation. Some make asthma difficult to control, while others cause milder, more controllable asthma. The hygiene hypothesis suggests that children who develop asthma are raised in environments that are too clean. There is also the contrasting idea that pollution, allergens, pets, and other things in the environment add to the possibility that asthma will develop.Question 11.8

Why is childhood asthma a concern for developmentalists?

Asthma's harm is more immediate that other disorders, such as obesity. Children with asthma often miss school and may be rushed to emergency rooms, gasping for air.