Brain Development

Recall that emotional regulation, theory of mind, and left–

Coordinating Connections

Increasing maturation results in connections between the various lobes and regions of the brain. Such connections are crucial for the complex tasks that children must master, which require “smooth coordination of large numbers of neurons” (Stern, 2013, p. 577). Certain areas of the brain, called hubs, are locations where massive numbers of axons meet. Hubs tend to be near the corpus callosum, and damage to them correlates with brain dysfunction (as in dementia and schizophrenia) (Crossley et al., 2014).

The importance of hubs means that the brain connections formed in middle childhood are crucial for healthy brain functioning. Particularly important are links between the hypothalamus and the amygdala, because emotions need to be regulated so learning can occur. Stress impairs these connections: Slow academic mastery in middle childhood is one more consequence of early maltreatment (Hanson et al., 2014).

One example of the need for brain connections is learning to read, perhaps the most important intellectual accomplishment of middle childhood. Reading is not instinctual: Our ancestors never did it, and until recent centuries, only a few scribes and scholars could make sense of marks on paper. Consequently, the brain has no areas dedicated to reading, the way it does for talking or gesturing (Sousa, 2014).

Instead, reading uses many parts of the brain—

Think Quick; Too Slow

Advance planning and impulse control are aided by faster reaction time, which is how long it takes to respond to a stimulus. Increasing myelination reduces reaction time every year from birth until about age 16. Skill at games is an obvious example, from scoring on a video game, to swinging at a pitch, to kicking a speeding soccer ball toward a teammate.

Many more complex examples involve social and academic skills. For instance, being able to discern when to utter a witty remark and when to stay quiet is something few 6-

Both quick replies and quick inhibition develop. Children become less likely to blurt out wrong answers but more likely to enjoy games that require speed. Interestingly, children with reading problems are slower as well as more variable in reaction time, and that itself slows down every aspect of reading (Tamm et al., 2014).

Pay Attention

Neurological advances allow children not only to process information quickly but also to pay special heed to the most important elements of their environment. Selective attention, the ability to concentrate on some stimuli while ignoring others, improves markedly at about age 7.

School-

For example in school, children listen, take notes, and ignore distractions (all difficult at age 6, easier by age 10). Unfazed by the din of the cafeteria, children react quickly to gestures and facial expressions. On the baseball diamond, older batters ignore the other team’s attempts to distract them, and fielders start moving into position as soon as the bat hits the ball.

Automatization

One final advance in brain function in middle childhood is automatization, the process by which a sequence of thoughts and actions is repeated until it becomes automatic. At first, almost all behaviors that are deliberate require careful thought. After many repetitions, neurons fire in sequence, and less thinking is needed because the firing of one neuron sets off a chain reaction: That is automatization.

Consider again learning to read. At first, eyes (sometimes aided by a guiding finger) focus intensely, painstakingly making out letters and sounding out each one. This leads to the perception of syllables and then words. Eventually, the process becomes so routine that as people drive along on a highway, they read billboards that they have no interest in reading. Children do the same, gradually learning to read without conscious control.

Automatic reading aids other academic skills. One longitudinal study of second-

Learning to speak a second language, to recite the multiplication tables, and to write one’s name also is slow at first but gradually becomes automatic. Habits and routines learned in childhood are useful lifelong—

Measuring the Mind

In ancient times, if adults were strong and fertile, that was usually enough to be considered a solid member of the community. A few wise men were admired, but most people were not expected to think quickly and profoundly. Over the centuries, though, we humans have placed higher and higher values on intelligence, and have developed ways to measure it.

Aptitude, Achievement, and IQ

In theory, aptitude is the potential to master a specific skill or to learn a certain body of knowledge. The brain functions which have just been described—

Measuring the brain directly is complicated, however. Therefore, intellectual aptitude is usually measured by answers to a series of questions. The underlying assumption is that there is one general thing called intelligence (often referred to as g, for general intelligence) and that correct answers measure g.

Originally, IQ tests produced a score that was literally an Intelligence Quotient: Mental age (the average chronological age of children who answer a certain number of questions correctly) was divided by the chronological age of the child who took the test. The result of that division (the quotient) was multiplied by 100.

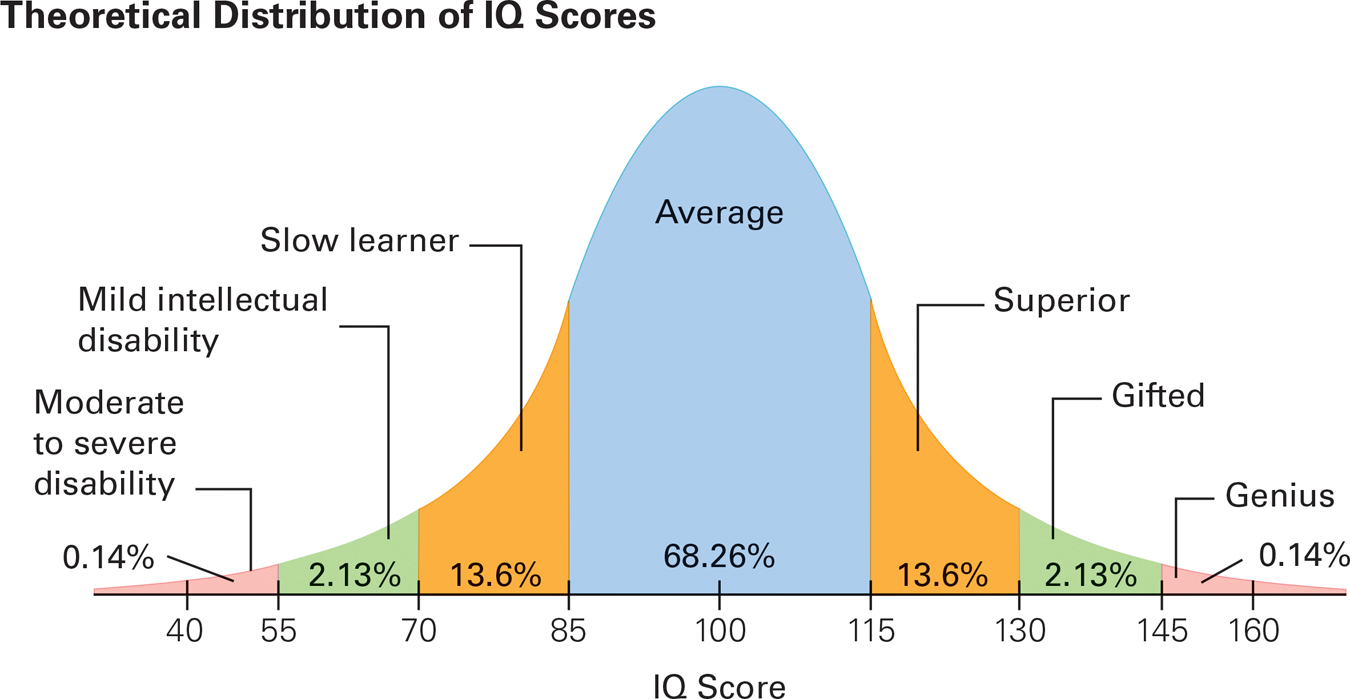

OBSERVATION QUIZ If a person’s IQ is 110, what category is he or she in?

He or she is average. Anyone with a score between 85 and 115 has an average IQ.

Thus if the average 10-

If a 10-

In Theory, Most People Are Average Almost 70 percent of IQ scores fall within the normal range. Note, however, that this is a norm-

In theory, achievement is what has actually been learned, not learning potential (aptitude). School achievement tests compare scores to norms established for each grade. For example, children of any age who read as well as the average third-

The words in theory precede the definitions of aptitude and achievement above because, although potential and accomplishment are supposed to be distinct, the data find substantial overlap. IQ and achievement scores are strongly correlated.

It was once assumed that aptitude was a fixed characteristic, present at birth. Longitudinal data show otherwise. Young children with a low IQ can become above average or even gifted adults, like my nephew David (discussed in Chapter 1). Indeed, the average IQ scores of entire nations have risen substantially every decade for the past century—

Most psychologists now agree that the brain is like a muscle, affected by mental exercise—

Criticisms of Testing

Since scores change over time, IQ tests are much less definitive than they were once thought to be. Some scientists doubt whether any single test can measure the complexities of the human brain, especially if the test is designed to measure g, one general aptitude. According to some experts, children inherit many abilities, some high and some low, rather than any g (e.g., Q. Zhu et al., 2010).

Two leading developmentalists (Sternberg and Gardner) are among those who believe that humans have multiple intelligences, not just one. Gardner originally described seven intelligences: linguistic, logical-

Although every normal person has some of all nine intelligences, Gardner believes each individual excels in particular ones. For example, someone might be gifted spatially but not linguistically (a visual artist who cannot describe her work) or might have interpersonal but not naturalistic intelligence (an astute clinical psychologist whose houseplants die). Gardner’s concepts regarding multiple intelligences influence the curriculum in many primary schools. For instance, children might be allowed to demonstrate their understanding of a historical event via a poster with drawings instead of writing a paper with a bibliography.

Especially for Teachers What are the advantages and disadvantages of using Gardner’s nine intelligences to guide your classroom curriculum?

The advantages are that all the children learn more aspects of human knowledge and that many children can develop their talents. Art, music, and sports should be an integral part of education, not just a break from academics. The disadvantage is that they take time and attention away from reading and math, which might lead to less proficiency in those subjects on standard tests and thus to criticism from parents and supervisors.

Sternberg described three kinds of intelligence: analytic, creative, and practical (1985, 2011). He contends that schools emphasize analysis (academics), but that creative and practical intelligence should also be valued. He added a fourth type of intelligence—

One needs creativity to generate novel ideas, analytical intelligence to ascertain whether they are good ideas, practical intelligence to implement the ideas and persuade others of their value, and wisdom to ensure that the ideas help reach a common good.

[Sternberg, 2012, p. 21]

Gardner, Sternberg, and many other scholars find that cultures and families dampen or encourage particular intelligences. For instance, if two children are born with creative, musical intelligence, the child whose parents are musicians is more likely to develop musical intelligence than a child whose parents are tone-

Every test reflects the culture of the people who create, administer, and take it. This is obvious for achievement tests: A child may score low because of home, school, or culture, not because of ability. Indeed, IQ tests are still used partly because achievement tests do not necessarily reflect aptitude.

Scores on aptitude tests are also influenced by culture. Some experts have tried to develop tests that are culture-

An obvious precaution, required by most IQ tests, is that a friendly, trained adult ask questions of an individual student, in order to avoid cultural test-

Brain Scans

One way to indicate aptitude is to measure the brain directly, avoiding the cultural biases of written exams or individual questions. Brain scans do not correlate with scores on IQ tests in childhood, but they do in adolescence (Brouwer et al., 2014). That suggests that one or the other of these tests is flawed when measuring the intelligence of children. The brain seems to have several localized hubs and lobes, which suggests multiple intelligence, but overall speed of reaction seems a characteristic of the entire brain, which may underlie g. Variation is vast in children’s brains, which makes experts hesitant to argue for any one interpretation of IQ tests and brain scans (e.g., Goddings & Giedd, 2014).

For example, although it seems logical that less brain activity means less intelligence, that is not always the case. In fact, automatization reduces the need for brain activity, so the smartest children might have less active brains. Another puzzle is that a thicker cortex sometimes correlates with high IQ, but cortex thinness predicts greater vocabulary in 9-

Neuroscientists agree, however, on three conclusions:

Brain development depends on specific experiences. Thus, a brain scan is accurate only for the moment at which is done.

Brain development continues throughout life: Middle childhood is a crucial time, but developments before and after these years are also significant for brain functioning.

Children with disorders often have unusual brain patterns, and training their brains may help. However, brain complexity and normal variation mean that diagnosis and remediation are far from perfect.

This leads to the final topics of this chapter, children with special needs and how they should be taught.

SUMMING UP During middle childhood, neurological maturation allows faster, more automatic reactions. Selective attention enables focused concentration in school and in play. IQ tests, which measure aptitude for learning, compare mental age to chronological age. Actual learning is measured by achievement tests.

As children and cultures adapt to changing contexts, IQ scores change much more than was originally imagined. Some scientists believe that certain abilities, perhaps speed of thought and working memory, undergird general intelligence, known as g. However, the concept that intelligence arises from one underlying aptitude is challenged by several scientists who believe that people have not just one type of intelligence but multiple intelligences. Further challenges to traditional IQ tests come from social scientists, who find marked cultural differences in what children are taught to do, and from neuroscientists, who see that brain activity does not reliably correlate with IQ scores.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 11.9

Why does quicker reaction time improve the ability to learn?

With quicker reaction time, children can read and write faster, retrieve information more quickly, and make decisions rapidly. This allows for more information to be processed, leading to better understanding.Question 11.10

How does selective attention make it easier for a child to sit in a classroom?

Selective attention allows children to focus on one thing while “tuning out” all competing stimuli.Question 11.11

When would a teacher give an aptitude test instead of an achievement test?

Teachers might give an aptitude test to see which students have the potential to do well in a specific course of study as opposed to an achievement test, which measures what the student has already learned.Question 11.12

If the theory of multiple intelligences is correct, should IQ tests be discarded? Why or why not?

No. IQ tests should not be discarded because they provide a standardized measure of general intelligence. In addition, IQ and achievement scores are strongly correlated.Question 11.13

Which intellectual abilities are more valued than others in the United States? Give examples.

Logical, language, and mathematical abilities are valued over music or artistic ability. Society places a greater emphasis on academics than the creative arts.Question 11.14

Should brain scans replace traditional intelligence tests? Why or why not?

No. Brain scans should not replace traditional tests because the interpretation of brain scans is not straightforward. Since many areas of a young child's brain are activated simultaneously and then, with practice, automatization reduces the need for brain activity, the smartest children might have less active brains. Similarly, some research finds that a thick cortex correlates with higher ability but also that thickness develops more slowly in gifted children. Brain scan results do not correlate well with written IQ tests, so it appears that the two types of assessments are measuring different things.