Developmental Psychopathology

Some children have special needs because of their brain and behavior patterns. Developmental psychopathology links the study of usual development with the study of special needs (Cicchetti, 2013b; Hayden & Mash, 2014). Every topic already described, including “genetics, neuroscience, developmental psychology, … must be combined to understand how psychopathology develops and can be prevented” (Dodge, 2009, p. 413).

At the outset, four general principles should be emphasized.

Abnormality is normal. Most children sometimes act oddly. At the same time, children with serious disorders are, in many respects, like everyone else.

Disability changes year by year. Most disorders are comorbid, which means that more than one problem is evident in the same person. Which particular disorder is most disabling at a particular time changes, as does the degree of impairment.

Life may be better or worse in adulthood. Prognosis is difficult. Many children with severe disabilities (e.g., blindness) become productive adults. Conversely, some conditions (e.g., conduct disorder) may become more disabling.

Diagnosis and treatment reflect the social context. Each individual interacts with the surrounding setting—

including family, school, community, and culture— to modify, worsen, or even create psychopathology.

Special Needs in Middle Childhood

Developmental psychopathology is relevant lifelong because “[e]ach period of life, from the prenatal period through senescence, ushers in new biological and psychological challenges, strengths, and vulnerabilities” (Cicchetti, 2013b, p. 458). Turning points, opportunities, and past influences are always apparent.

However in middle childhood, children are grouped by age. For some parents and teachers it suddenly becomes obvious that a particular child differs markedly from others the same age. Fortunately, the effects of most disorders can be mitigated if treatment is early and properly targeted.

Therein lies a problem: Although early treatment is more successful, early and accurate diagnosis is difficult, not only because many disorders are comorbid but also because symptoms differ by age. As you learned in Chapter 7, infants have temperamental differences that might or might not become problems, and Chapter 10 explained that some aggression is normal. Difference is not necessarily deficit, but that does not mean that all differences are benign.

Two basic principles of developmental psychopathology lead to caution in diagnosis and treatment (Hayden & Mash, 2014; Cicchetti, 2013b). First is multifinality, which means that one cause can have many (multiple) final manifestations. For example, an infant who has been flooded with stress hormones may become a hypervigilant or an unusually calm kindergartener, may be easily angered or quick to cry, or may not be affected at all.

The second principle is equifinality (equal in final form), which means that one symptom can have many causes. For instance, a nonverbal child may be autistic, hard of hearing, not fluent in the dominant language, or pathologically shy.

The complexity of diagnosis is evident in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), often referred to as DSM-

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Someone with attention-

Some impulsive, active, and creative actions are normal for children. However, children with ADHD

are so active and impulsive that they cannot sit still, are constantly fidgeting, talk when they should be listening, interrupt people all the time, can’t stay on task, … accidentally injure themselves.” All this makes them “difficult to parent or teach.”

[Nigg & Barkley, 2014, p. 75]

They tend to have academic difficulties; they are less likely to graduate from high school and college; they become unhappy with themselves and with everyone else.

Problems with Diagnosis

There is no biological marker for ADHD. Current research, nonetheless, suggests the origin of the disorder is neurological, with problems in brain regulation either because of genes, complications of pregnancy, or toxins (such as lead) (Nigg & Barkely, 2014).

ADHD is comorbid with other conditions, including biological problems such as sleep deprivation or allergic reactions. Explosive rages, later followed by deep regret, are typical for children with many disorders, including ADHD. One surprising comorbidity is deafness: Children with severe hearing loss often are affected in balance and activity, and that seems to make them prone to developing ADHD (Antoine et al., 2013). In this way, ADHD is an example of equifinality; many causes produce one disorder.

Although the U.S. rates of children with ADHD were about 5 percent in 1980, recent data find that 7 percent of all 4-

OBSERVATION QUIZ Is he able to write?

Yes, ADHD does not preclude reading and writing. However, ADHD makes it hard to think and write at the same time. That's why his teacher writes for him. She also tries to keep him focused on his work—

Rates of ADHD in most other nations are lower than in the United States, but they are rising everywhere (e.g., Al-

Misdiagnosis. If ADHD is diagnosed when another disorder is the problem, treatment might make the problem worse, not better (Miklowitz & Cicchetti, 2010). Many psychoactive drugs alter moods, so a child with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (formerly called childhood-

onset bipolar disorder) might be harmed by drugs that help children with ADHD. Drug abuse. Although drugs that reduce the symptoms of ADHD reduce one cause of later drug abuse, some adolescents may use a diagnosis of ADHD in order to obtain amphetamines with a doctor’s prescription.

Normal behavior considered pathological. In young children, high activity, impulsiveness, and curiosity are normal. If a normal child is diagnosed as abnormal, that may affect the child’s self-

concept and adult expectations. Could normal male activity be one reason ADHD is much more common in boys than girls?

Especially for Health Workers Parents ask that some medication be prescribed for their kindergarten child, who they say is much too active for them to handle. How do you respond?

Medication helps some hyperactive children but not all. It might be useful for this child, but other forms of intervention should be tried first. Compliment the parents on their concern about their child, but refer them to an expert in early childhood for an evaluation and recommendations. Behavior-

Many adults (71 percent in one study) who were diagnosed with ADHD as children say they no longer have the condition (Barbaresi et al., 2013). Do people overcome or outgrow ADHD, or do adults minimize their symptoms, or do parents and teachers over-

Treatment for ADHD involves: (1) training for the family and the child, (2) special education for teachers, and (3) medication. But, as equifinality suggests, most disorders vary in causes, so treatment that helps one child does not necessarily work for another (Mulligan et al., 2013).

Drug Treatment for ADHD and Other Disorders

Because many adults are upset by what young children normally do and because any physician can write a prescription to quiet a child, thousands of children may be overmedicated. But because many parents do not recognize that their child needs help, or they are suspicious of drugs and psychologists (Moldavsky & Sayal, 2013; Rose, 2008), thousands of children may suffer needlessly.

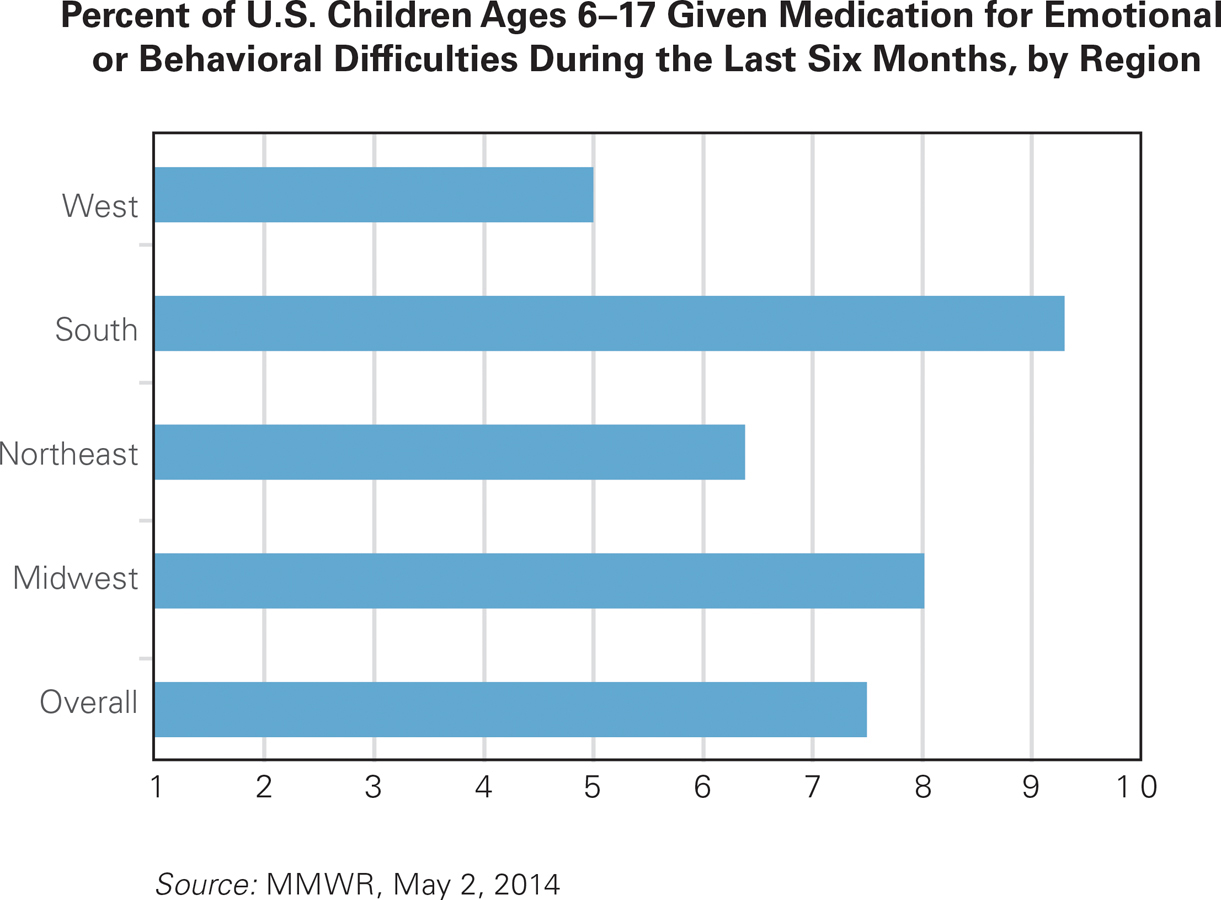

In the United States, more than 2 million people younger than 18 take prescription drugs to regulate their emotions and behavior (see Figure 11.4). The rates are about 14 percent for teenagers (Merikangas et al., 2013), about 10 percent for 6-

One Child In Every Classroom Or maybe two, if the class has more than 20 students or is in Alabama. This figure shows the percent of 6-

The most commonly prescribed drug for ADHD is Ritalin, but at least 20 other psychoactive drugs treat depression, anxiety, intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, and many other conditions in middle childhood. Many child psychologists believe that drugs can be helpful, and they worry that the public discounts the devastation and lost learning that occur when a child’s serious disorder is not recognized or treated.

But all agree that finding the best drug at the right strength is difficult, in part because each child’s genes and personality are unique, and in part because children’s weight and metabolism change every year. Given all that, it is troubling that only half of all children who take psychoactive drugs are evaluated and monitored by a mental health professional (Olfson et al., 2010). Most experts also believe that contextual interventions (instructing parents and teachers on child management) should be tried first (Daley et al., 2009; Leventhal, 2013; Pelham & Fabiano, 2008) and provide the best long-

Drugs may help, but they are not a cure. In one careful study, when children with ADHD were given appropriate medication, carefully calibrated, they were more able to concentrate. However, eight years later, many had stopped taking their medicine. At this follow-

Ethnic differences are found in parent responses, teacher responses, and treatment for children with ADHD symptoms. In the U.S., it seems that, when African American and Hispanic children are diagnosed with ADHD, their parents are less likely to give them medication compared to European American parents (Morgan et al., 2013). However, genes, culture, health care, education, religion, and stereo types could all affect ethnic differences. As two experts explain, “disentangling these will be extremely valuable to improving culturally competent assessment in an increasingly diverse society” (Nigg & Barkely, 2014, p. 98).

When appropriately used, drugs for ADHD may help children make friends, learn in school, feel happier, and behave better. These drugs also seem to help adolescents and adults with ADHD (Surman et al., 2013). However, as the just-

a case to study

Lynda Is Getting Worse

Even experts differ in diagnosis of problems and recommended treatments. For instance, one study asked 158 child psychologists—

Parents say Lynda has been hyperactive, with poor boundaries and disinhibited behavior since she was a toddler…. Lynda has taken several stimulants since age 8. She is behind in her school work, but IQ normal….

At school she is oppositional and “lazy” but not disruptive in class. Psychological testing, age 8, described frequent impulsivity, tendencies to discuss topics unrelated to tasks she was completing, intermittent expression of anger and anxiety, significantly elevated levels of physical activity, difficulties sitting still, and touching everything. Over the past year Lynda has become very angry, irritable, destructive and capricious. She is provocative and can be cruel to pets and small children. She has been sexually inappropriate with peers and families, including expressing interest in lewd material on the Internet, Playgirl magazine, hugging and kissing peers. She appears to be grandiose, telling her family that she will be attending medical school, or will become a record producer, a professional wrestler, or an acrobat. Throughout this period there have been substantial marital difficulties between the parents.

[Dubicka et al., 2008, appendix p. 3]

Most (81 percent) of the clinicians diagnosing Lynda thought she had ADHD, and most thought she had another disorder as well. The Americans were likely to suggest a second and third disorder, with 75 percent of them specifying bipolar disorder. Only 33 percent of the British psychologists said bipolar (Dubicka et al., 2008).

Clinicians did not finger the family context or teacher’s attitudes. This is a serious omission, since, for both nature and nurture reasons, parents who have ADHD or mood disorders are more likely to have children with disorders. It would have made sense for the parents to be tested and treated as well as 8-

In this case, her parents thought Lynda had ADHD since toddlerhood; a pediatrician agreed, and at age 8 put her on drugs. Now, at age 11, she seems to be getting worse, not better, while her parents are increasingly hostile to each other. Family interaction, especially a close parental alliance, might have forstalled the problem.

Of course, it is impossible to know what would have happened if intensive intervention had taken place for the entire family when Lynda was a toddler. Might marital problems have been avoided? In any case, the four principles of developmental psychopathology suggest that developmental patterns and social contexts needed to be considered. That might have led to improvement, as apparently three years of medication did not.

Specific Learning Disorders

The DSM-

Video: Dyslexia: Expert and Children

@2016 MACMILLAN

Some learning disabilities are not debilitating (e.g., the off-

Dyslexia

The most commonly diagnosed learning disorder is dyslexia—unusual difficulty with reading. No single test accurately diagnoses dyslexia (or any learning disability) because every academic achievement involves many distinct factors (Riccio & Rodriguez, 2007). One child with a reading disability might have trouble sounding out words but might excel in comprehension and memory of printed text; another child might have the opposite problem. Dozens of types and causes of dyslexia have been identified, so no single strategy will help every child with dyslexia (O’Brien et al., 2012).

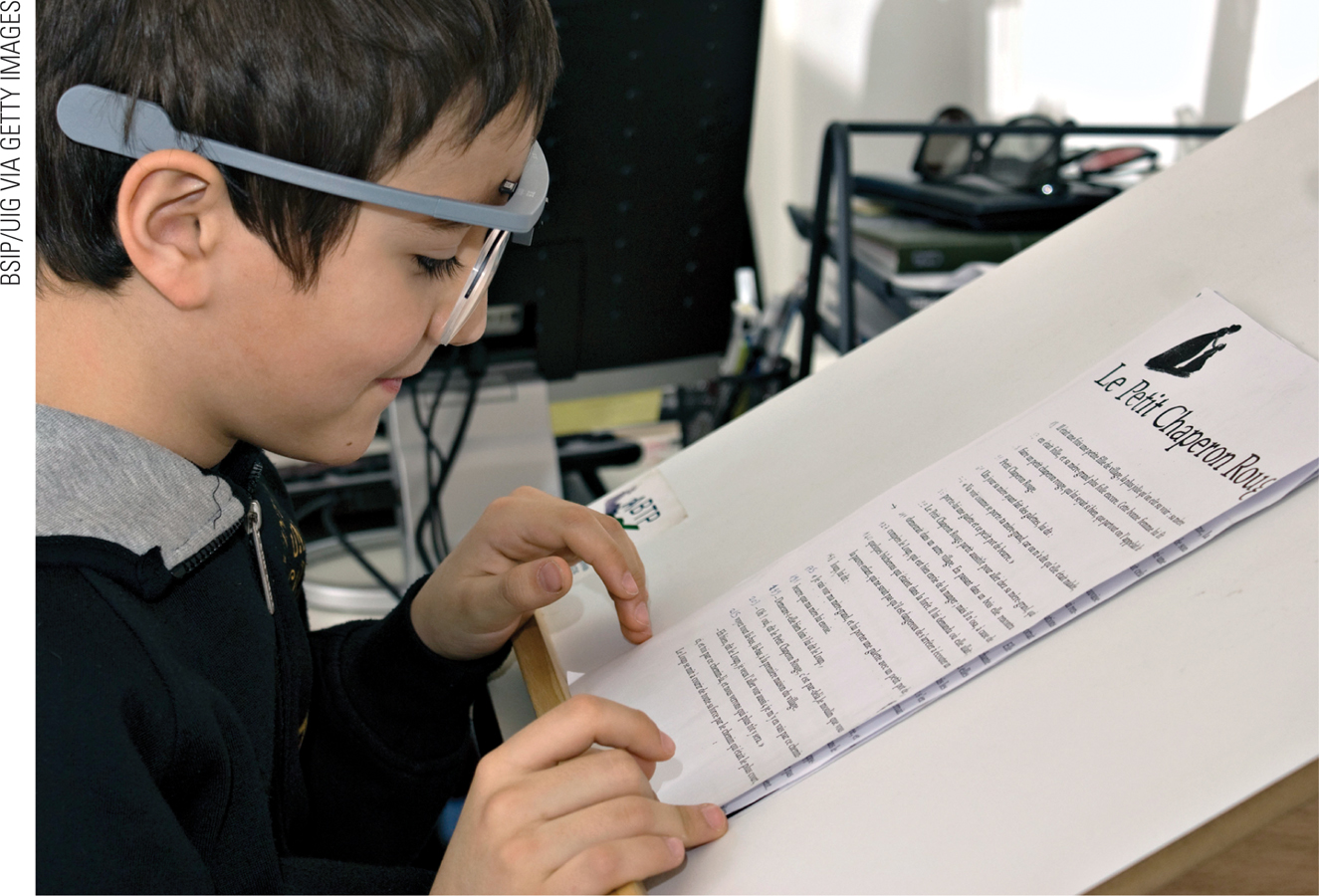

Early theories hypothesized that visual difficulties—

Traditionally, dyslexia was diagnosed only if a child had difficulty reading despite normal IQ, normal hearing and sight, and normal behavior. This approach usually meant waiting until the third grade or so, when the reading difficulty became apparent. Now difficulty with the basic skills for beginning reading (naming letters and sounds, hearing rhymes) is recognized in kindergarten, and children receive earlier remediation.

Dyscalculia and Dysgraphia

Another common learning disorder is dyscalculia, unusual difficulty with math. For example, when asked to estimate the height of a normal room, second-

Dyslexia and dyscalculia are often comorbid, although each originates from several distinct parts of the brain. Early encouragement with counting and calculating (long before first grade) can teach a child math basics, limiting dyscalculia and avoiding the emotional stress children feel if other children grasp math more easily (Butterworth et al., 2011).

Similar concerns regard very poor spelling and writing, known as dysgraphia, and again early remediation is useful, because the origin is probably in the brain as well as the social context. Remediation is best done early, at age 6 not age 10, not only because the brain is more flexible but also because the young child’s eagerness to learn has not yet been crushed by failure. Every person, learning disabled or not, has strengths and interests, and almost everyone can learn basic skills if they are given extensive and targeted teaching, encouragement, and practice.

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Of all the children with special needs, those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are probably the most troubling. Their problems are severe, but both causes and treatments are hotly disputed. Thomas Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, describes the parents and other advocates of children with autism as “the most polarized, fragmented community I know” (quoted in Solomon, 2012, p. 280).

Many children with ASD show symptoms in the first year of life, but some seem normal and then suddenly regress at about age 2 or 3, perhaps because a certain level of brain development, or a particular medical insult, occurs (Klinger et al., 2014). Most are diagnosed at age 4 or later (MMWR, March 28, 2014).

Symptoms

Video: Current Research into Autism Spectrum Disorder explores why the causes of ASD are still largely unknown.

Autism spectrum disorder is characterized by woefully inadequate social understanding, coupled with repetitive or restrictive patterns of behavior, such as lining up toys by color rather than playing with them, or fascination with trains, lights, or spinning objects. More than a century ago, autism was considered rare, affecting fewer than 1 in 1,000 children with “an extreme aloneness that, whenever possible, disregards, ignores, shuts out anything … from the outside” (Kanner, 1943).

Years ago, children who developed slowly, and who would now be likely to be diagnosed with ASD, were usually diagnosed as being “mentally retarded” or as having a “pervasive developmental disorder.” (The term “mental retardation,” which was used in DSM-

Much has changed. Far more children are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, and far fewer with intellectual disability. In the United States, among 8-

The DSM-

Children with any form of ASD find it difficult to understand the emotions of others, which makes them feel alien, like “an anthropologist on Mars,” as Temple Grandin, an educator and writer with ASD, expressed it (quoted in Sacks, 1995). Consequently, they are less likely to talk or play with anyone, and they are delayed in developing theory of mind. Severely impaired children never speak, rarely smile, and play for hours with one object (such as a spinning top or a toy train). Mildly impaired children appear normal at first, and may be talented in some specialized area, such as drawing or geometry. Many (46 percent) score in the ‘normal’ or ‘above normal’ range on IQ tests (MMWR, March 28, 2014).

Most children with autism spectrum disorder show signs in early infancy (no social smile, for example, or less gazing at faces and eyes than most toddlers). Some improve by age 3; others deteriorate. Late onset occurs with several brain disorders, including Rett syndrome, in which a newborn girl (boys with the Rett gene never survive) has “normal psychomotor development through the first 5 months after birth,” but then her brain develops very slowly, severely limiting movement and language (Bienvenu, 2005).

Many children with ASD have an opposite problem—

As mentioned above, in the United States far more children are found to have ASD now than in 1990. The incidence of this disorder may have actually increased, or the definition has expanded, or more children receive that diagnosis because educational services are more available (Klinger et al., 2014).

Underlying the estimate of frequency is the problem that no definitive measure diagnoses autism spectrum disorder: Many adults are socially inept, insensitive to other people’s emotions, and poor at communication—

A related issue is whether autism is a disorder needing a cure, or whether the real problem is in parents and society that expect everyone to be fluent talkers, gregarious, and flexible—

Treatment

The neurodiversity perspective is one reaction to the many treatments that converge on autism. When a child is diagnosed with ASD, parental responses vary from irrational hope to deep despair, from blaming doctors and chemical additives to feeling guilty for what they did wrong. Many parents sue schools, or doctors, or the government; many spend all their money and change their lives; many subject their children to treatments that are, at best, harmless, and at worst, painful and even fatal.

Andrew Solomon (2012) writes about one child, who was medicated with

Abilify, Topamax, Seroquel, Prozac, Ativan, Depakote, trazodone, Risperdal, Anafranil, Lamictal, Benadryl, melatonin, and the homeopathic remedy, Calms Forté. Every time I saw her, the meds were being adjusted again…. [He also describes] physical interventions—

[p. 229, 270]

Equifinality certainly applies to ASD: A child can have autistic symptoms for many reasons; no single gene causes the disorder. That makes treatment difficult; an intervention that seems to help one child proves worthless for another. It is known, however, that biology is crucial (genes, copy number abnormalities, birth complications, prenatal injury, perhaps chemicals during fetal or infant development) and that family nurture is not the cause of ASD but may modify it. Social and language engagement of the child early in life seems the most promising treatment.

SUMMING UP Many children have special learning needs that originate with problems in the development of their brains. Developmental psychopathologists emphasize that no child is typical in every way; the passage of time sometimes brings improvement and sometimes not. Children with attention-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 11.15

How does normal childhood behavior differ between the United States and Asia?

The environment dictates through social norms what is considered acceptable behavior. Children in the United States are encouraged to be independent individuals and excel as such. Pride is encouraged. Children in collectivist cultures like Japan are encouraged to be more concerned with the benefit their work has to the entire group/class over themselves as individuals. Modesty is encouraged and pride is discouraged.Question 11.16

What is the difference between multifinality and equifinality?

Multifinality means that one cause can have many final manifestations. Exposure to stress hormones in infancy might lead to hypervigilance or unusual calmness by kindergarten. It is hard to predict how a factor will affect an individual's outcomes. Equifinality means that one symptom can have many causes. A child who does not speak might be autistic or hard of hearing, might not speak the language well, or might be pathologically shy. It is important to eliminate the competing explanations when making a diagnosis.Question 11.17

Why is medication recommended for children with ADHD?

Medication is used to help ADHD children control their emotions and behavior. It makes it easier for them to attend to what is going on in the classroom so they can succeed academically. It also makes them less impulsive, leading to better social relationships.Question 11.18

Why might parents ask a doctor to prescribe Ritalin for their child?

If their child has a diagnosis of ADHD, they may request this prescription to quiet their child and allow the child to focus, especially at school.Question 11.19

What are dyslexia, dyscalculia, and dysgraphia?

Dyslexia, dyscalculia, and dysgraphia are all learning disabilities. Dyslexia is unusual difficulty with reading, whereas dyscalculia is unusual difficulty with math. Dysgraphia refers to difficulties with spelling and writing.Question 11.20

How might an adult have a learning disability that has never been diagnosed?

Because there is no single test for diagnosing a learning disability, and because most learning disabilities are not debilitating, many people with learning disabilities reach adulthood unaware that they have a disability. Instead, they spent their school years feeling inadequate, ashamed, and stupid. They may not have achieved their fullest academic potential, unless they developed their own coping strategies.Question 11.21

What are the three primary signs of autism spectrum disorder?

There are three main signs of autism spectrum disorder: 1) problems in social interaction and the social use of language, 2) difficulty understanding emotion, and 3) restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, and activities.Question 11.22

What are the implications of neurodiversity?

The main implication of neurodiversity is that it suggests that differences in neurological functioning are normal and therefore that ALL variations in cognition and behaviour should be accepted and celebrated in society.