Special Education

The overlap of the biosocial, cognitive, and psychosocial domains is evident to developmentalists, as is the need for parents, teachers, therapists, and researchers to work together to help each child. However, deciding whether or not a child should be designated as needing special education is not straightforward, nor is it closely related to specific special needs.

Labels, Laws, and Learning

In the United States, recognition that the distinction between normal and abnormal is not clear-

According to the 1975 Education of All Handicapped Children Act, children with special needs must be educated in the least restrictive environment (LRE). That law has been revised several times, but the goal remains that children should not be segregated from other children unless it is not possible to remediate problems within the regular classroom.

Consequently, LRE usually means educating children with special needs in a regular class, a practice once called mainstreaming, rather than in a special classroom or school. Sometimes a child is sent for a few hours a week to a resource room, with a teacher who provides targeted tutoring. Sometimes a class is an inclusion class, which means that children with special needs are “included” in the general classroom, with “appropriate aids and services” (ideally from a trained teacher who works with the regular teacher).

A more recent educational strategy is called response to intervention (RTI) (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009; Shapiro et al., 2011; Ikeda, 2012). All children are taught specific skills; for instance, learning the sounds that various letters make. Then the children are each tested, and those who did not master the skill receive special “intervention”—practice and individualized teaching, usually within the regular class. Then they are tested again, and, if need be, intervention occurs again. Only when a child does not respond adequately to repeated, focused intervention is the child referred for testing and observation to diagnose the problem.

RTI is used in some nations with success (e.g., Sahlberg, 2011) and is now implemented in many U.S. schools. Most children respond to intervention, but those who do not are then tested to determine if they have special needs. In that case, the school proposes an individual education plan (IEP) with the parents.

The basic assumption of the IEP is that schools need to “design learning pathways for each individual sufferer.” The label, or specific diagnosis, is supposed to help target effective remediation. Yet this rarely occurs in practice (Butterworth & Kovas, 2013, p. 304). Instead, the special needs that attract most research on remediation are not the more common ones. One example: In the United States, “research funding in 2008–

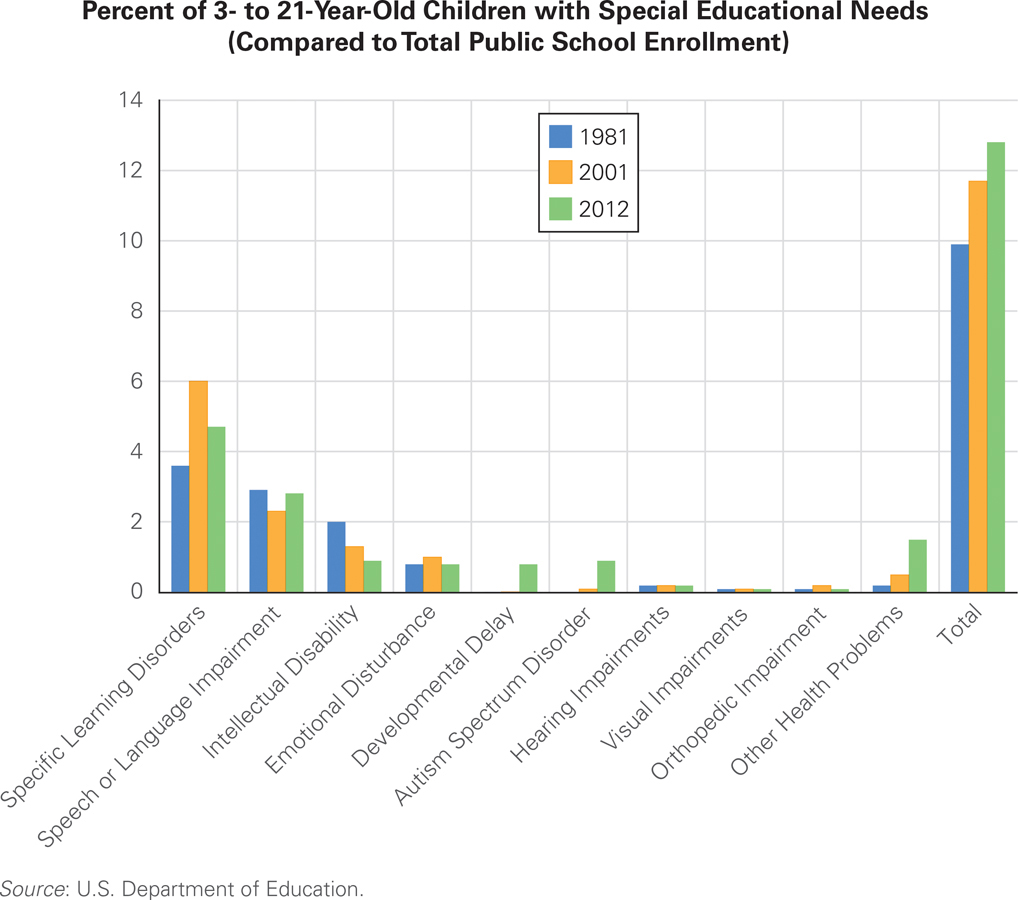

In the United States, historical shifts are notable in which children are recognized by educators as having special needs, and what their needs are labeled. As Figure 11.5 shows, the proportion of children designated with special needs rose in the United States from 10 percent in 1980 to 13 percent in 2011, primarily because more children are called learning disabled or autistic (National Center for Education Statistics, 2013b).

Nature or Nurture Communities have always had some children with special needs, with physical, emotional, and neurological disorders. In some eras, and today in some nations, the education of such children was neglected. Indeed, many children were excluded from normal life even before they quit trying. Now in the United States, every child is entitled to school. Categories have changed, probably because of nurture, not nature. Thus, teratogens and changing parental and community practice probably caused the rise in autism spectrum disorder and developmental delay, the decrease in intellectual disability, and the fluctuation in learning disorders apparent here.

There is no separate category for ADHD. To receive special services, children with ADHD are often designated as having a specific learning disorder. Since most disorders are comorbid, the particular special needs category in the school system may not be the diagnosis given by a psychologist. One result is that teachers, therapists, and parents may work at cross-

Internationally, the connection between special needs and education varies, again for cultural and historical reasons more than child-

Gifted and Talented

Children who are unusually gifted are often thought to have special needs as well, but they are not covered by federal laws in the United States. Instead, each U.S. state selects and educates gifted and talented children in a particular way, a variation that leads to controversy.

A scholar writes: “The term gifted … has never been more problematic than it is today” (Dai, 2010, p. 8). Educators, political leaders, scientists, and everyone else argue about who is gifted and what should be done about them. Are gifted children unusually intelligent, or talented, or creative? Should they be skipped, segregated, enriched, or left alone?

A hundred years ago, the definition of gifted was simple: high IQ. A famous longitudinal study followed a thousand “genius” children, all of whom scored above 140 on the Stanford-

A hundred years ago, school placement was simple for high IQ children. They were taught with children who were their mental age, not their chronological age. This practice was called acceleration. Today that is rarely done because many accelerated children never learned how to get along with others. As one woman remembers:

Nine-

[Rachel, quoted in Freeman, 2010, p. 27]

Calling herself a weed suggests that she never overcame her conviction that she was less cherished than the other children. Her intellectual needs may have been met by her skipping two grades, but her emotional and social needs were severely neglected.

Historically, many famous musicians, artists, and scientists were child prodigies whose fathers recognized their talent (often because the father was talented) and taught them. Often they did not attend regular school, because laws requiring attendance did not exist. Mozart’s father transcribed his earliest pieces and toured Europe with his gifted son. Picasso’s father removed him from school in second grade so he could create all day.

That solution also had pitfalls. Although intense early education at home nourishes talent, neither Mozart nor Picasso had happy adult lives. Moreover, Picasso said he never learned to read or write, and Mozart had a poor understanding of math and money. Similar patterns are still apparent, as exemplified by gifted athletes (e.g., Tiger Woods and Steffi Graf) as well as those in less public specialties. Here is one example:

Sufiah Yusof started her maths degree at Oxford [the leading University in England] in 2000, at the age of 13. She too had been dominated and taught by her father. But she ran away the day after her final exam. She was found by police but refused to go home, demanding of her father in an email: “Has it ever crossed your mind that the reason I left home was because I’ve finally had enough of 15 years of physical and emotional abuse?” Her father claimed she’d been abducted and brainwashed. She refuses to communicate with him. She is now a very happy, high-

[Freeman, 2010, p. 286]

Some children who might need special education are unusually creative (Sternberg et al., 2011). They are divergent thinkers, finding many solutions and even more questions for every problem. Such students joke in class, resist drudgery, ignore homework, and bedevil their teachers. They may become innovators, inventors, and creative forces of the future.

Creative children do not conform to social standards. They are not convergent thinkers, who choose the correct answer on school exams. One such person was Charles Darwin, whose “school reports complained unendingly that he wasn’t interested in studying, only shooting, riding, and beetle-

Neuroscience has recently discovered that children who develop their musical talents with extensive practice in early childhood grow specialized brain structures, as do child athletes and mathematicians. Since plasticity means that children learn whatever their context teaches, special talents may be enhanced with special education, an argument for elementary school teaching to accommodate creative children.

Since both acceleration and intense parental tutoring have led to later problems, a third education strategy has become popular, at least in the United States. Children who are bright, talented, and/or creative—

Classes for gifted students require unusual teachers, smart and creative, able to appreciate divergent thinking and challenge the very bright. They must be flexible: providing a 7-

Should such teachers be available only for the gifted? Every child may need talented teachers and individualized instruction, no matter what the child’s abilities or disabilities may be. Many educators complain that the system of education in the United States, where each school district and sometimes each school hires and assigns teachers, results in the best teachers having the most able students, when it should be the opposite. This trend is furthered by tracking, putting children with special needs together, and allowing private or charter schools to select certain students and leave the rest behind.

Some nations educate all children together, assuming that the best learners are not naturally gifted but are able to work harder at learning. Thus, the teacher’s job is to motivate and challenge every child. U.S. law says all children can learn, and it is the job of schools to teach them. Every special and ordinary form of education can benefit by applying what we know about children’s minds (De Corte, 2013). That is the topic of the next chapter.

SUMMING UP No child learns or behaves exactly like another, and no educational strategy always succeeds. Various strategies are apparent not only for children with disabilities but also for those who are unusually gifted and talented. Mainstreaming and inclusion of children with special needs occur because educators believe that children benefit from learning with other children. It is not straightforward to balance that belief with the need for some children to have an individual education plan, or a gifted and talented class.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 11.23

What do mainstreaming and inclusion have in common?

Both involve educating children with special needs in the general education classroom or the least restrictive environment (LRE). Mainstreaming is the education of children with special needs in the regular class rather than a special classroom or school. In some instances, the child is sent to a special classroom with a teacher who provides targeted tutoring. Inclusion means that children with special needs are “included” in the general classroom with appropriate aids and services (ideally from a trained teacher who works with the regular teacher).Question 11.24

Why is response to intervention considered an alternative to special education?

Response to intervention (RTI) is an educational strategy intended to help children who demonstrate below–average achievement in early grades, using special intervention. All children are taught specific skills; for instance, learning the sounds that various letters make. Then the children are each tested, and those who did not master the skill receive special “intervention”—practice and individualized teaching, usually within the regular class. (In the past, these children may have been identified for special education services before intervention attempts were even introduced.) Then they are tested again and if need be, intervention occurs again. Only when a child does not respond adequately to repeated, focused intervention is the child referred for testing and observation to diagnose the problem. Question 11.25

Why are children who are smarter than their peers no longer allowed to skip grades?

A hundred years ago, school placement was simple for high IQ children. They were taught with children who were their mental age, not their chronological age. This practice was called acceleration. Today that is rarely done because many accelerated children never learned how to get along with others.Question 11.26

What are the arguments for and against special classes for gifted children?

Acceleration and intense parental tutoring have led to later problems, such as not learning age–appropriate social skills and a poor understanding of certain academic skills. In the United States, another education strategy has become popular: Children who are bright, talented, and/or creative— all the same age but each with special abilities— are taught together in their own classroom. Ideally such children are neither bored nor lonely; each is challenged and appreciated by their classmates.