Language

As you will remember, many aspects of language advance during early childhood. By age 6, children have mastered the basic vocabulary and grammar of their first language. Many also speak a second language fluently. Those linguistic abilities allow the formation of a strong knowledge base, enabling some school-

Vocabulary

By age 6, children know the names of thousands of objects, and they use many parts of speech—

Understanding Metaphors

Especially for Parents You’ve had an exhausting day but are setting out to buy groceries. Your 7-

Your son would understand your explanation, but you should take him along if you can do so without losing patience. You wouldn’t ignore his need for food or medicine, so don’t ignore his need for learning. While shopping, you can teach vocabulary (does he know pimientos, pepperoni, polenta?), categories (root vegetables, freshwater fish), and math (which size box of cereal is cheaper?). Explain in advance that you need him to help you find items and carry them and that he can choose only one item that you wouldn’t normally buy. Seven-

Metaphors, jokes, and puns are finally comprehended. Some jokes (“What is black and white and read all over?” “Why did the chicken cross the road?”) are funny only during middle childhood. Younger children don’t understand why they provoke laughter, and teenagers find them lame and stale, but the new cognitive flexibility of 6-

Indeed, a lack of metaphorical understanding, even if a child has a large vocabulary, signifies cognitive problems (Thomas et al., 2010). Humor, or lack of it, is a diagnostic tool.

Many adults do not realize how difficult it is for young children or adults who are learning a new language to grasp figures of speech. The humorist James Thurber remembered what he called “the enchanted private world” of his early boyhood:

In this world, businessmen who phoned their wives to say they were tied up at the office sat roped to their swivel chairs, and probably gagged, unable to move or speak except somehow, miraculously, to telephone…. Then there was the man who left town under a cloud. Sometimes I saw him all wrapped up in the cloud and invisible…. At other times it floated, about the size of a sofa, above him wherever he went…. [I remember] the old lady who was always up in the air, the husband who did not seem able to put his foot down, the man who lost his head during a fire but was still able to run out of the house yelling.

[Thurber, 1999, p. 40]

Metaphors are context-

Because school-

is like a jellyfish, which has a deadly sting and vicious bite and tentacles which could squeeze your throat and make your bronchioles get smaller and make breathing harder. Or like a boa constrictor squeezing life out of you.

[quoted in Peterson & Sterling, 2009, p. 97]

That boy was terrified of his disease, which he considered evil and dangerous—

Adjusting Vocabulary to the Context

One aspect of language that advances markedly in middle childhood is pragmatics, already defined in Chapter 9. Pragmatics is evident in the contrast between talking formally to teachers (never calling them a rotten egg) and informally with friends (who can be rotten eggs or worse). As children master pragmatics, they become more adept at making friends. Shy 6-

Mastery of pragmatics allows children to change styles of speech, or “linguistic codes,” depending on their audience. Each code includes many aspects of language—

Some children may not realize that informal expressions are wrong in formal language. All children need instruction to become fluent in the formal code because the logic of grammar (whether who or whom is correct or how to spell you) is almost impossible to deduce. The peer group teaches the informal code, and each local community transmits dialect, metaphors, and pronunciation.

Educators must teach the formal code. However, they should not make children feel that their neighborhood or family grammar or pronunciation is shameful.

Bilingual Education

Code changes are obvious when children speak one language at home and another at school. Every nation includes many such children; most of the world’s 6,000 languages are not school languages. For instance, English is the language of instruction in Australia, but 17 percent of the children speak one of 246 other languages at home (Centre for Community Child Health & Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, 2009).

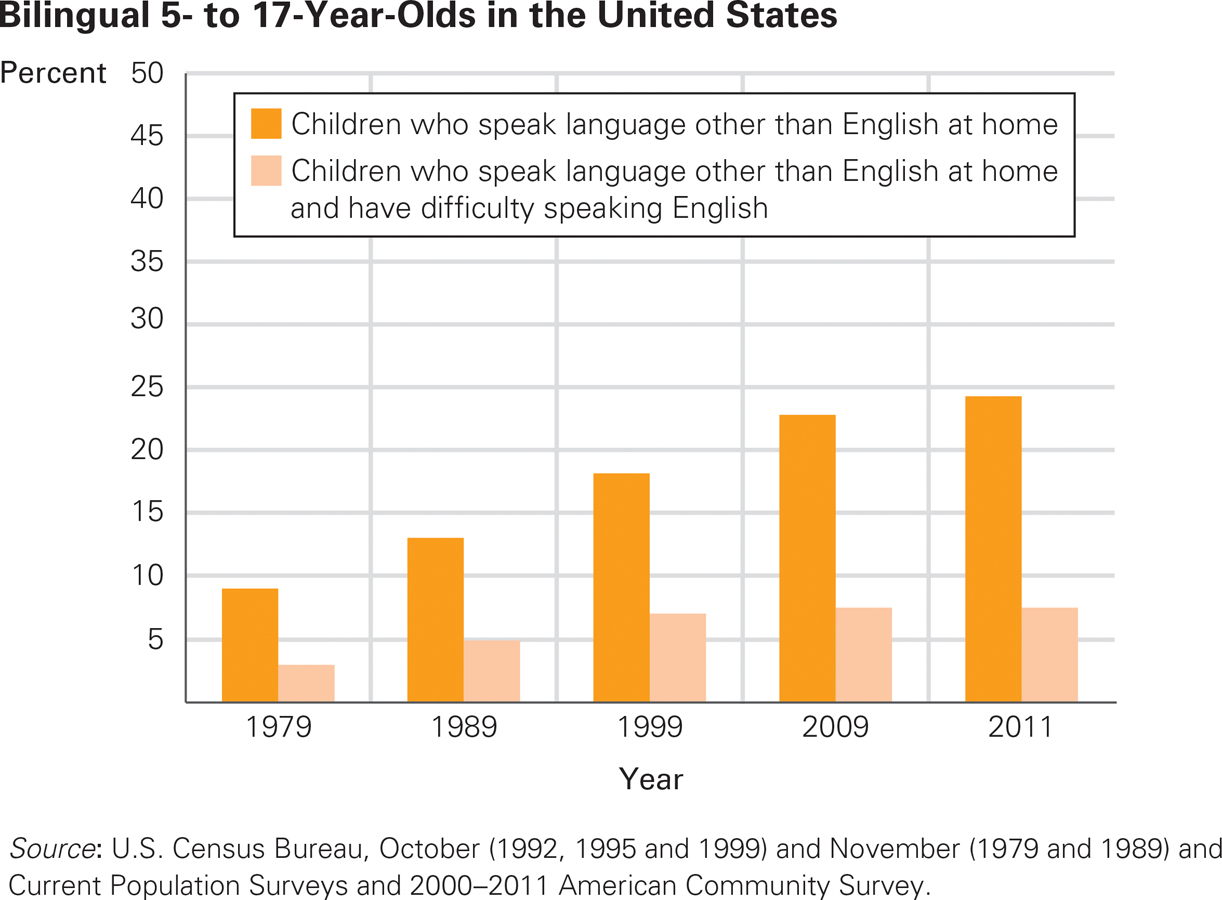

In the United States, almost 1 school-

Hurray for Teachers More children in the United States are now bilingual and more of them speak English well, from about 60 percent in 1980 to 75 percent in 2011.

In addition, many other children speak a dialect of English that differs from the pronunciation and grammar taught at school. All these alternate codes have distinct patterns of timing, grammar, and emphasis, as well as vocabulary, so all require much more than literal translation.

If a child learns only one language in the early years, but then masters a second language during middle childhood, the brain must adjust. A study found no brain differences between monolingual and bilingual children if they spoke both languages from infancy. However, from about age 4 through adolescence, the older children are when they learn a second language, the more likely their brains will reveal differences that result from the need to accommodate their dual languages.

Specifically, children who learn a second language later have greater cortical thickness on the left side (the language side) and thinness on the right (Klein et al., 2014). This reflects what we know about language learning: School-

In the United States, some children of every ethnicity are called ELLs, or English Language Learners, based on their proficiency in speaking, writing, and reading English. Among U.S. children with Latin American heritage, those who speak English well are much better at reading than those who do not. Age, schooling, and SES all have an effect, but even some of higher SES may be less adept at reading than the average European American child (Howard et al., 2014). Culture may be the reason, as their learning style may not be the same as their teachers’ teaching style, even though they speak and understand English well.

Teaching approaches range from immersion, in which instruction occurs entirely in the new language, to the opposite, in which children are taught in their first language until the second language can be taught as a “foreign” tongue (a strategy rare in the United States but common elsewhere). Between these extremes lies bilingual schooling, with instruction in two languages, and ESL (English as a Second Language), with all non-

Methods for teaching a second language sometimes succeed and sometimes fail, with the research not yet clear as to which approach is best (Gandara & Rumberger, 2009). The success of any method seems to depend on the literacy of the home environment (frequent reading, writing, and listening in any language helps); the warmth, training, and skill of the teacher; and the national context.

Specifics differ for each state and grade level, but the general trends are dismal. ELLs fall more behind their peers with each passing grade, becoming high school dropouts at higher rates than other students their age. For instance, in Pennsylvania in 2009, the percent of fourth graders proficient in reading was 74 percent for the non-

Using an information-

For these bilingual children, knowledge of Spanish follows another trajectory. It does not improve much during kindergarten and first grade (presumably because children focus on English), and then advances markedly at the end of second grade (Rojas & Iglesias, 2013). Schools can affect this by having Spanish classes for all the youngest children, so those whose home language is Spanish will appreciate their mother tongue. These are averages; specifics of learning and effective educational strategies depend on the particular experiences of the child at home and school, just as information-

Differences in Language Learning

Learning to speak, read, and write the school language is pivotal for primary school education. Some differences in ability may be innate: A child with a language disability will have trouble with both the school and home languages.

It is a mistake to assume that a child who does not speak English well is learning disabled (difference is not deficit), but it is also is a mistake to assume that such a child’s only problem is lack of English knowledge (deficits do occur among all children, no matter what their background). To discover whether a child has difficulty learning language, it is best to test in the home language—

Although some children from every language background have disabilities, most of the language gap between one child and another is the result of the social context, not brain abnormality. Two crucial factors are SES and expectations.

Socioeconomic Status

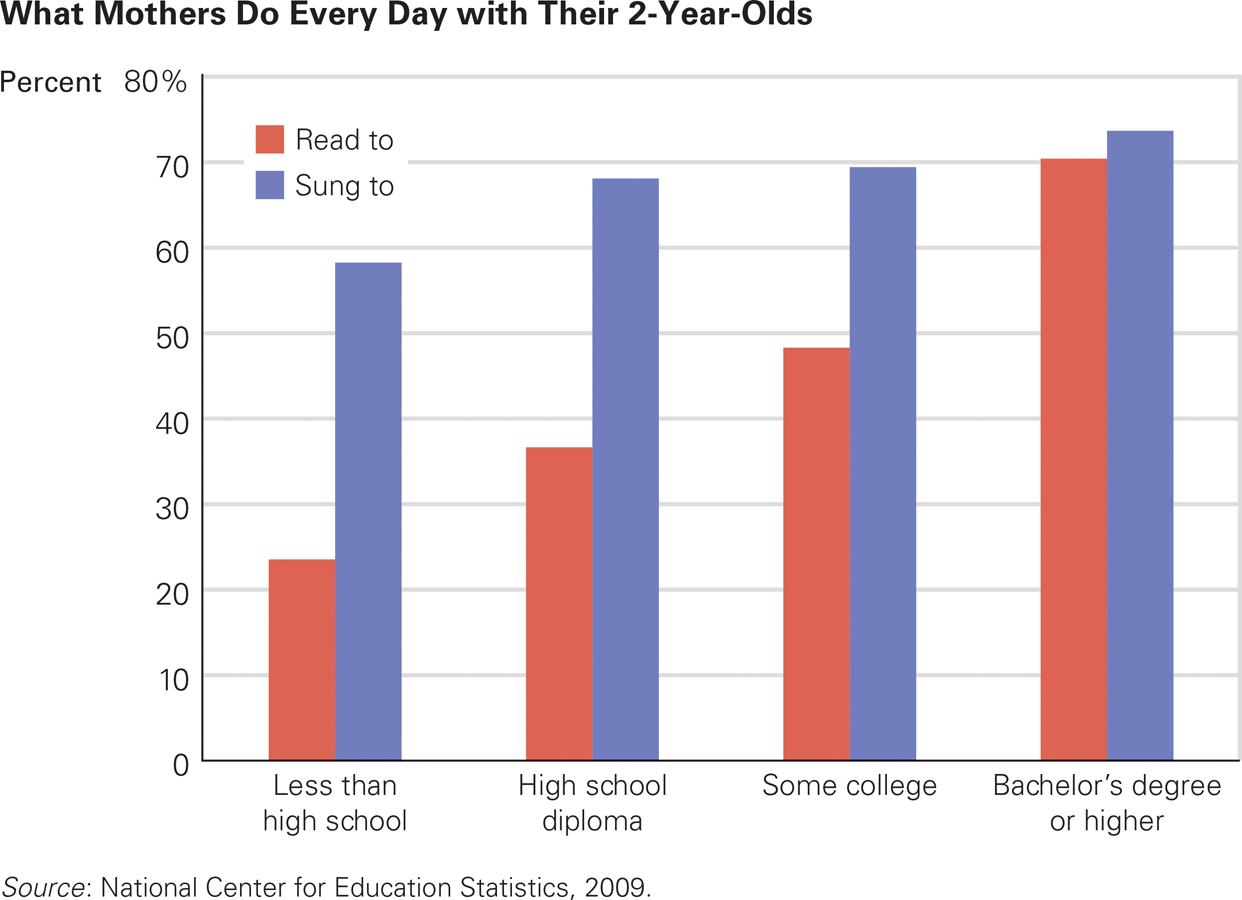

Red Fish, Blue Fish As you can see, most mothers sing to their little children, but the college-

Decades of research throughout the world have found a strong correlation between academic achievement and socioeconomic status. Language is a major reason. Not only do children from low-

With regard to language learning, the information-

However, one factor seems clearly a cause, not just a correlate, of language proficiency: language heard during the first five years of life. If it is extensive and elaborate, the child is likely to speak and then read well.

The mothers’ education seems crucial. Many less-

Even independent of income, research has shown that children who grow up in homes with many books accumulate, on average, three years more schooling than children who grow up in homes with no books (Evans et al., 2010), presumably because the parents of the latter group rarely read. Language exposure is the direct cause here, not household income. Indeed, children from high-

Book-

OBSERVATION QUIZ What in the daughter’s behavior suggests that maternal grooming is a common event in her life?

Her posture is straight; her hands are folded; she is quiet, standing while her mother sits. All this suggests that this scene is a frequent occurrence.

Ideally, parents read to, sing to, and converse with each child daily, and also provide extensive vocabulary about various activities. For example, as parent and child are walking down the street: “The sidewalk is narrow (or wide, or cracked, or cement) here.” “See the wilted rose. Is it red or magenta or maroon?” “That truck has six huge tires. Why does it have so many?” Children offer comments of their own, and adults can respond with “Yes,” “That’s interesting,” “I never thought of that”—never ignoring the child or commanding, “Be quiet!”

Expectations

Beyond direct language encouragement, a second cause of low achievement in middle childhood is teachers’ and parents’ expectations. Although substantial research has found that children are influenced by adults’ positive expectations, the relationship between expectation and achievement becomes complicated as children grow older. One crucial factor seems to be whether parents and teachers have shared expectations for the children, rather than working at cross-

Expectations need to be explicit, not idealistic. For instance, children should know that they are expected to read for pleasure rather than watch television, to learn advanced academic vocabulary (e.g., negotiate, evolve, allegation, deficit), and to have important ideas that the parent will listen to attentively and with respect. Remember, though, that authoritarian parenting, which includes high standards, can backfire if it is not accompanied by warmth.

Expectations do not necessarily follow along income lines, especially among immigrant families. For low-

The worst result of low expectations by adults is that they are transmitted to the child. Schoolchildren may internalize their parents’ or teachers’ belief that they will not learn. Expectations, motivation, and achievement go hand in hand. Qualities such as grit, resilience, and emotional regulation—

a view from science

True Grit

Thousands of social scientists—

Many scientists agree that executive control processes with many names (grit, emotional regulation, conscientiousness, resilience, executive function, effortful control) develop over the years of middle childhood and are crucial for cognitive growth. Over the long term, these aspects of character predict achievement in high school, college, and adulthood. Developmentalists disagree about exactly which qualities are crucial for achievement, with grit considered crucial by some and not others (Ivcevic & Brackett, 2014; Duckworth & Kern, 2011), but no one denies that success depends on personality traits, not just on intellect.

This concept appears in almost every chapter of this textbook, from the discussion of plasticity in Chapter 1 to the evidence in Chapter 11 regarding children who overcome notable learning disabilities. One of the best longitudinal studies we have (the Dunedin study of an entire cohort of children from New Zealand) found that measures of self-

Among the many influences on children, a pivotal one is having at least one adult who encourages accomplishment. For many children, that adult is their mother, although, especially when parents are neglectful or abusive, a teacher, a religious leader, a coach, or someone else can be the mentor and advocate who helps a child overcome adversity (Masten, 2014).

Remember that school-

All the mothers were married and middle-

Although the researchers noted these universal aspects of the mother–

This distinction is evident in the following two excepts:

First, Tim and his American mother discussed a “not perfect” incident.

Mother: I wanted to talk to you about … that time when you had that one math paper that … mostly everything was wrong and you never bring home papers like that….

Tim: I just had a clumsy day.

Mother: You had a clumsy day. You sure did, but there was, when we finally figured out what it was that you were doing wrong, you were pretty happy about it … and then you were happy to practice it, right? … Why do you think that was?

Tim:

I don’t know, because I was frustrated, and then you sat down and went over it with me, and I figured it out right with no distraction and then I got it right.

Mother: So it made you feel good to do well?

Tim: Uh-

Mother: And it’s okay to get some wrong sometimes.

Tim: And I, I never got that again, didn’t I?

The next excerpt occurred when Ren and his Chinese mother discuss a “good attitude or behavior.”

Mother: Oh, why does your teacher think that you behave well?

Ren: It’s that I concentrate well in class.

Mother: Is your good concentration the concentration to talk to your peer at the next desk?

Ren: I listen to teachers.

Mother: Oh, is it so only for Mr. Chang’s class or is it for all classes?

Ren: Almost all classes like that….

Mother: So you want to behave well because you want to get an … honor award. Is that so?

Ren: Yes.

Mother: Or is it also that you yourself want to behave better?

Ren: Yes. I also want to behave better myself.

[Li et al., 2014, p. 1218]

Both Tim and Ren are likely to be good students in their respective schools. When parents support and encourage their child’s learning, almost always the child masters the basic skills required of elementary school students, and almost never does the child become crushed by life experiences. Instead, the child has sufficient strengths to overcome most challenges (Masten, 2014).

However, the specifics of parental encouragement affect the child’s achievement. Some research has found that parents in Asia emphasize that education requires hard work, whereas parents in North America stress the joy of learning. It may be that some parents push their children to excel because they believe that their children’s accomplishments reflect on them. The result, according to one group of researchers, is that U.S. children are happier but less accomplished than Asian ones (Ng et al., 2014).

SUMMING UP Children continue to learn language rapidly during the school years. They become more flexible, logical, and knowledgeable, figuring out the meanings of new words and grasping metaphors, jokes, and compound words. Many converse with friends using informal speech and master formal code in school. They learn whatever grammar and vocabulary they are taught, and they succeed at pragmatics—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 12.10

How does learning language progress between the ages of 6 and 10?

By age 6, children have mastered the basic vocabulary and grammar of their first language. Many also speak a second language fluently. Those linguistic abilities allow the formation of a strong knowledge base, enabling some school–age children to learn up to 20 new words a day and to apply complex grammar rules. In addition to vocabulary, children make impressive gains in the understanding of metaphors. Mastery of pragmatics allows them to use their language in more ways and to understand and comprehend subtleties. They also become adept at switching between formal and informal speech based on their audience. Question 12.11

How does a child’s age affect the understanding of metaphors and jokes?

A child has to have a good grasp of pragmatics before he or she can appreciate metaphors or jokes that make a play on words.Question 12.12

Why would a child’s linguistic code be criticized by teachers but admired by friends?

The informal code used with friends often includes curse words, slang, gestures, and intentionally incorrect grammar. Peers approve of such violations, whereas adults wish to teach children the formal code of standard speech based on grammatical rules.Question 12.13

What factors in a child’s home and school affect language-

learning ability? In order to learn grammar and advanced vocabulary, a child has to be around people who use it well. In homes where standard English is not the language used, what children hear is different than what they hear and learn at school. Children from low–SES families may not be exposed to a rich language or extensive vocabularies. Their parents rarely read to them, which prevents them from learning “book language.” Thus, they tend to construct sentences with fewer words. Teachers' and parents' expectations also play an important role. Although substantial research has found that children are influenced by adults' positive expectations, the relationship between expectation and achievement becomes complicated as children grow older. One crucial factor seems to be whether parents and teachers have shared expectations for the children, rather than working at cross– purposes. Also important is that children internalize those expectations rather than feel the need to rebel against them. The worst result of low expectations by adults is that they are transmitted to the child. Schoolchildren may internalize their parents' or teachers' belief that they will not learn. Expectations, motivation, and achievement go hand in hand. Qualities such as grit, resilience, and emotional regulation— all affected by parents, teachers, and the child's own hopes— are crucial for learning at every stage of life Question 12.14

What are three research conclusions regarding U.S. children whose home language is not English?

1) ELLs who learn to speak English well are much better at reading than those that do not. 2) Age, schooling, and SES all have an impact on the success of ELLs. 3) Specifics differ for each state and grade level but the general trends indicate that ELLs fall more behind their peers with each passing grade, becoming high school dropouts at higher rates than other students their age.Question 12.15

How and why does low SES affect language learning?

Low–SES children are not exposed to complex sentences and, therefore, do not create them. They have fewer vocabulary words at their disposal, know less grammar, and compose shorter sentences. Low– SES parents do not often read aloud to their children. Thus, the children may struggle to learn concepts of print.