The Nature of the Child

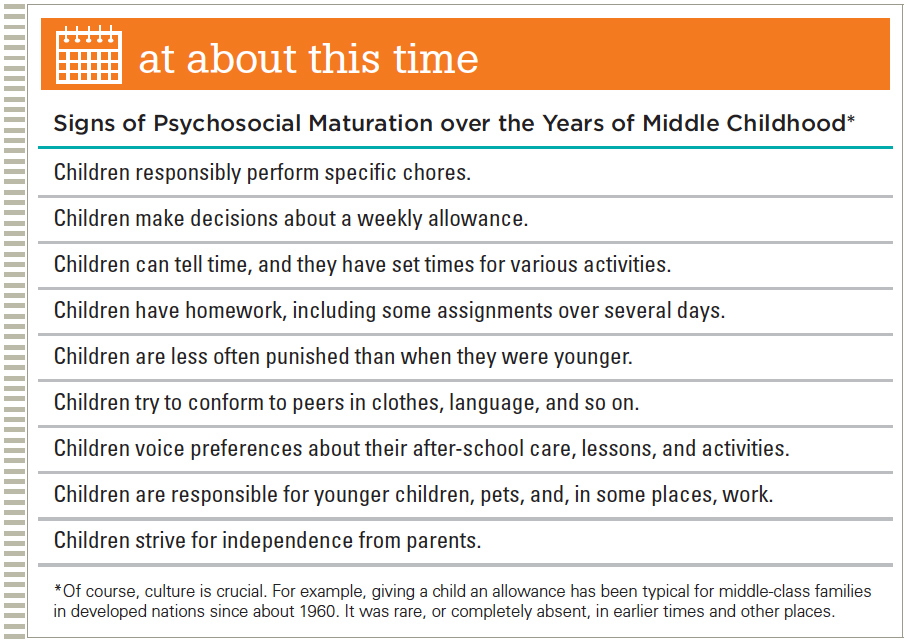

As explained in the previous two chapters, steady growth, brain maturation, and intellectual advances make middle childhood a time for more independence (see At About This Time). One practical result is that between ages 6 and 11, children learn to care for themselves. They not only hold their own spoon but also make their own lunch, not only zip their own pants but also pack their own suitcases, not only walk to school but also organize games with friends.

They venture outdoors alone, if their parents let them, and some experts think that parents should do just that (Rosin, 2014). Over the same years, parent–

Industry and Inferiority

Throughout the centuries and in every culture, school-

Erikson’s Insights

With regard to his fourth psychosocial crisis, industry versus inferiority, Erikson noted that the child “must forget past hopes and wishes, while his exuberant imagination is tamed and harnessed to the laws of impersonal things,” becoming “ready to apply himself to given skills and tasks” (Erikson, 1963, pp. 258, 259).

Think of learning to read and add, both of which are painstaking and boring. For instance, slowly sounding out “Jane has a dog” or writing “3 + 4 = 7” for the hundredth time is not exciting. Yet school-

This was apparent in Chapter 12, in the comparison of mothers from Taiwan and New England. When Tim’s mother helped him figure out how to do a particular kind of math problem that had him “clumsy” in class, she wrote out a page of problems for him, and then he did “the whole thing lickety-

Overall, children judge themselves as either industrious or inferior—deciding whether they are competent or incompetent, productive or useless, winners or losers. Self-

Freud on Latency

Sigmund Freud described this period as latency, a time when emotional drives are quiet (latent) and unconscious sexual conflicts are submerged. Some experts complain that “middle childhood has been neglected at least since Freud relegated these years to the status of an uninteresting ‘latency period’” (Huston & Ripke, 2006, p. 7).

But in one sense, Freud was correct: Sexual impulses are absent, or at least hidden. Even when children were betrothed before age 12 (rare today but common earlier in some nations), the young husband and wife had little interaction.

Everywhere, boys and girls typically choose to be with others of their own sex. Indeed, boys who write “Girls stay out!” and girls who complain that “Boys stink!” are typical. From a developmental perspective, latency is a dynamic stage, not a gradual progression, as children shift away from sexual interests—

Self-Concept

As children mature, they develop their self-

The self-

Crucial during middle childhood is social comparison—comparing one’s self to others (Davis-

This means that some children—

Affirming pride is an important counterbalance, because, for all children, their increasing self-

In addition, because children think concretely during middle childhood, materialism increases, and attributes that adults might find superficial (hair texture, sock patterns) become important, making self-

Culture and Self-Esteem

Academic and social competence are aided by realistic self-

The same consequences occur if self-

High self-

Often in the United States, children’s successes are praised and teachers are wary of being critical, especially in middle childhood. For example, some schools issue report cards with grades ranging from “Excellent” to “Needs improvement” instead of from A to F. An opposite trend is found in the national reforms of education, explained in Chapter 12. Because of the No Child Left Behind Act, some schools are rated as failing. Obviously culture, cohort, and age all influence attitudes about high self-

One component of self-

Watch Video: Interview with Carol Dweck to learn about how children’s mindsets affect their intellectual development

For example, children who fail a test are devastated if failure means they are not smart. However, process-

Thus, as with most developmental advances, the potential for psychological growth is evident in the advance a child makes in self-

Resilience and Stress

In infancy and early childhood, children depend on their immediate families for food, learning, and life itself. Then “experiences in middle childhood can sustain, magnify, or reverse the advantages or disadvantages that children acquire in the preschool years” (Huston & Ripke, 2006, p. 2). Some children continue to benefit from supportive families, and others escape destructive family influences by finding their own niche in the larger world.

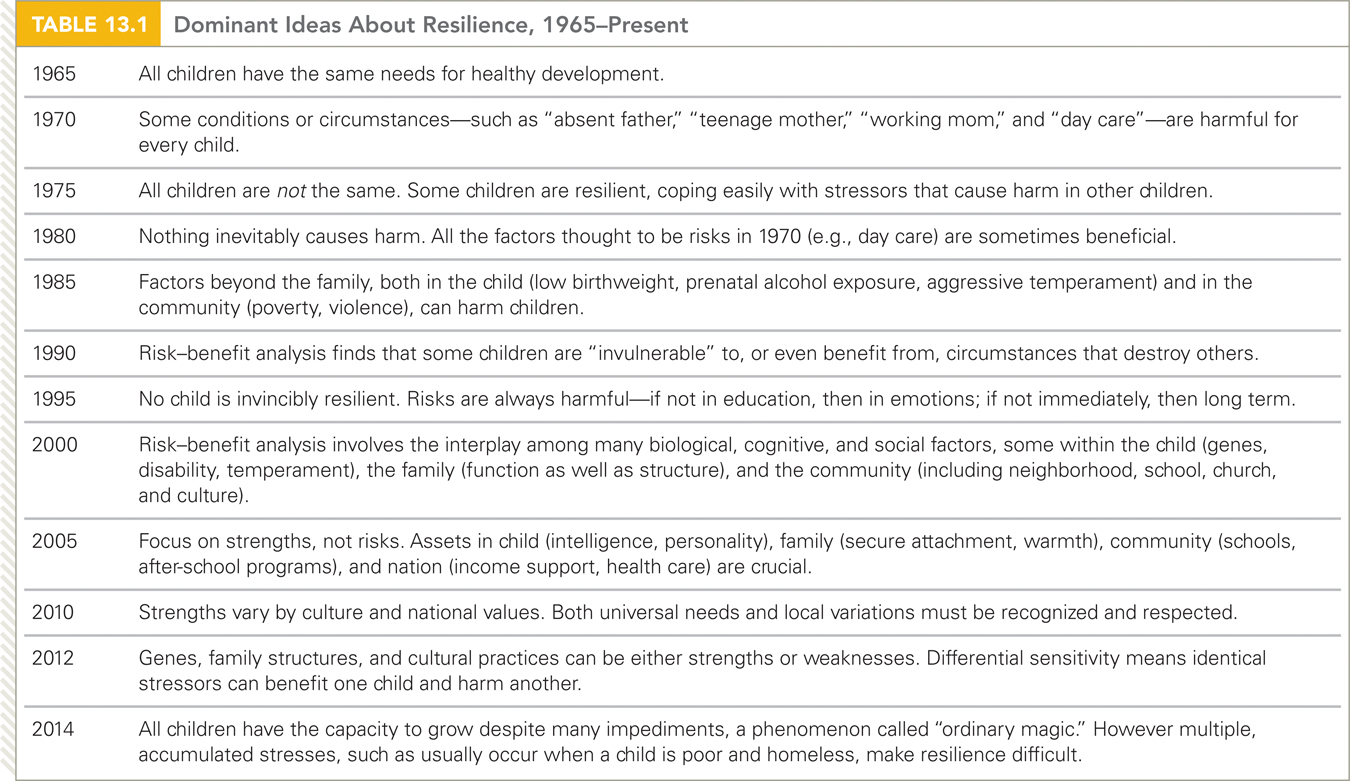

Surprisingly, some children seem unscathed by early experiences. They have been called “resilient” or even “invincible.” Current thinking about resilience (see Table 13.1), with insights from dynamic-

Differential susceptibility is apparent, not only because of genes but also because of early child rearing, preschool education, and sociocultural values. As Chapter 1 explains, some children are hardy, more like dandelions than orchids, but all are influenced by their situation (Ellis & Boyce, 2008).

Resilience has been defined as “a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity” (Luthar et al., 2000, p. 543) and “the capacity of a dynamic system to adapt successfully to disturbances that threaten system function, viability, or development” (Masten, 2014, p. 10). Note that both leading researchers emphasize three factors in their definitions:

Resilience is dynamic, not a stable trait. That means a given person may be resilient at some periods but not at others, and the effects from one period reverberate as time goes on.

Resilience is a positive adaptation to stress. For example, if parental rejection leads a child to a closer relationship with another adult, that is positive adaptation, not mere passive endurance. That child is resilient.

Adversity must be significant, a threat to the processes of development or even to life itself (viability).

Cumulative Stress

One important discovery is that stress accumulates over time, including stressful minor disturbances (called “daily hassles”). A long string of hassles, day after day, is more devastating than an isolated major stress. Almost every child can withstand one trauma, but repeated stresses make resilience difficult; “the likelihood of problems increased as the number of risk factors increased” (Masten, 2014, p. 14; Jaffee et al., 2007).

One international example comes from Sri Lanka, where many children in the first decade of the twenty-

The social context—

These war-

An example from the United States comes from children temporarily living in a shelter for homeless families. (Cutuli et al., 2013; Obradović, 2012). Compared to other children from the same kinds of families (typically high poverty, often single parent), they are “significantly behind their low-

Again, protective factors buffered the impact: Having a parent with them who was supportive and who provided affection, hope, and stable routines enabled some homeless children to be resilient.

This echoes research from England during World War II, when many children were sent to loving families in rural areas to escape the daily bombing of London. To the surprise of the researchers, those children who stayed in London, hearing bombs and frequently fleeing to air raid shelters, were more resilient than those who were physically safe but had no parent nearby (Freud & Burlingham, 1943).

Similar results were found in a longitudinal study of children exposed to a sudden, wide-

Cognitive Coping

Video Activity: Child Soldiers and Child Peacemakers examines the state of child soldiers in the world, and then explores how developmental components of adolescent cognition relate to the decisions of five teenage peace activists.

Obviously, these examples are extreme, but the general finding appears in other research as well. Disasters take a toll, but resilience is possible. Factors in the child (especially problem-

One pivotal factor is the child’s own interpretation of events (Lagattuta, 2014). Cortisol increases in low-

Think of people you know: Many adults whose childhood family income was low did not consider themselves poor. They may have had to share a bed with a sibling, and they may have eaten macaroni day after day, but that did not bother them because their parents seemed strong and happy, or at least not erratic and angry. They did not realize how poor they were. Therefore, poverty did not harm them lifelong.

In general, a child’s interpretation of a family situation (poverty, divorce, and so on) determines how it affects him or her. Some children consider the family they were born into a temporary hardship; they look forward to the day when they can leave childhood behind. If they also have personal strengths, such as problem-

The opposite reaction is called parentification, when children feel responsible for the entire family, acting as parents who take care of everyone, including their actual parents. Here again, the child’s interpretation is crucial.

If children feel burdened and wish they could have a carefree childhood, they are likely to suffer, but if they think they are helpful and their parents and community respect their contribution, they are likely to be resilient. This may explain a curious finding: European American children are more likely to suffer from parentification than African Americans are (Khafi et al., 2014).

In another example, children who endured hurricane Katrina were affected by their thoughts, positive and negative, more than by other expected factors, including their caregivers’ distress (Kilmer & Gil-

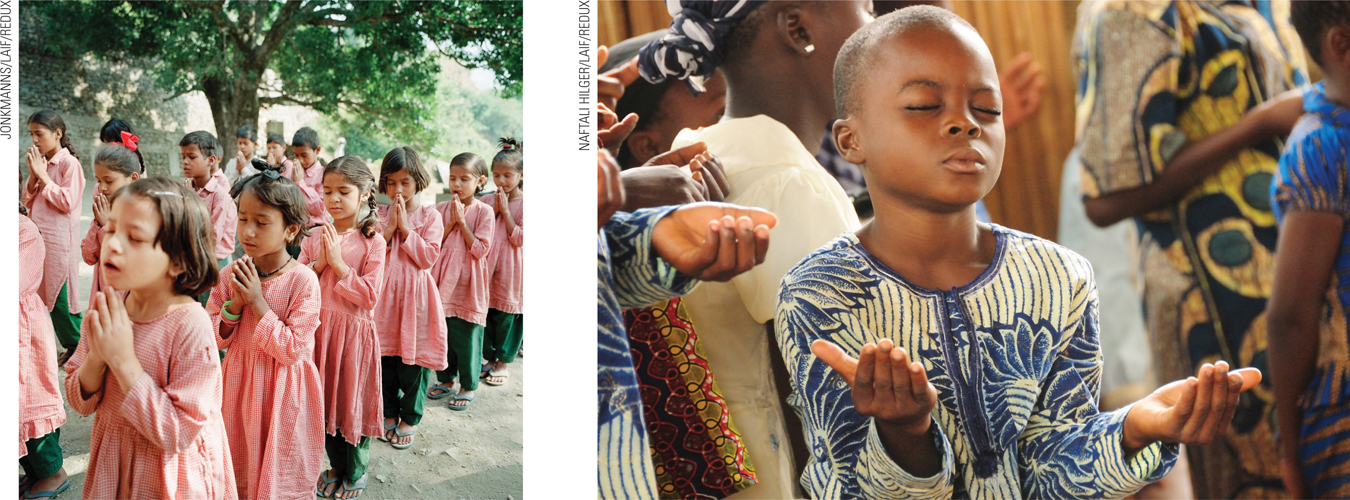

Prayer may also foster resilience, because it changes a person’s thinking. In one study, adults were required to pray for a specific person for several weeks. Their attitude about that person changed (Lambert et al., 2010). Ethics precludes such an experiment with children, but it is known that children often pray, expecting that prayer will make them feel better, especially when they are sad or angry (Bamford & Lagattuta, 2010). As already explained, expectations and interpretations can be powerful.

SUMMING UP Children advance in maturity and responsibility during the school years. According to Erikson, the crisis of industry versus inferiority generates feelings of confidence or self-

Often children develop more realistic self-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 13.1

How do Erikson’s stages for preschool and school-

age children differ? School–age children become consumed by a conflict between industry and inferiority, whereas preschool children are consumed by a conflict between initiative and guilt. School– age students enjoy practicing skills and collecting and organizing things. These children are intrinsically motivated to achieve, especially in school, and compare themselves to their peers. This leads to a reduction in self– esteem; they no longer have the “protective optimism” of the preschool years. School– age children are more sensitive to criticism than preschool children are, and it can lead to a feeling of inferiority. Question 13.2

Why is social comparison particularly powerful during middle childhood?

In preadolescence, the peer group becomes especially powerful because children compare themselves to others in order to form a realistic self–concept incorporating comparison to peers and judgments from the overall society. Question 13.3

Why do cultures differ in how they value pride or modesty?

The answer to this question has to do with how the culture views the individual. For example, students in the United States are taught to value independence, cultivate pride, and be their own personal “best.” Children in collectivist cultures, like Japan, are taught to value the good of the group over the independence of the individual and to cultivate modesty.Question 13.4

Why and when might minor stresses be more harmful than major stresses?

When “daily hassles” accumulate, they can become more devastating than an isolated major stress. Almost every child can withstand a single, major event, but repeated stresses make resilience difficult.Question 13.5

What factors in the social context help children cope with major disasters?

Major disasters can include such events as war, natural disasters, deaths of relatives, and homelessness. Disasters take a toll, but resilience is possible. Factors in the child (especially problem–solving ability), in the family (consistency and care), and in the community (good schools and welcoming religious institutions) all help children recover. Question 13.6

How might a child’s interpretation affect the ability to cope with repeated stress?

When a child doesn't take things personally or doesn't view negative situations as permanent, it is much more likely that the child will be resilient.