Puberty Begins

Puberty refers to the years of rapid physical growth and sexual maturation that end childhood, producing a person of adult size, shape, and sexuality. The forces of puberty are unleashed by a cascade of hormones that produce external growth and internal changes, including heightened emotions and sexual desires.

The process of puberty normally starts sometime between ages 8 and 14. Most physical growth and maturation ends about four years after the first signs appear, although some individuals (especially boys) add height, weight, and muscle until age 20 or so. Over the past decades the age of puberty has decreased, perhaps for both sexes, although the evidence is more solid for girls (Biro et al., 2013; Herman-

For girls, the observable changes of puberty usually begin with nipple growth. Soon a few pubic hairs are visible, followed by a peak growth spurt, widening of the hips, the first menstrual period (menarche), a full pubic-

Video: The Timing of Puberty

TOBKATRINA/SHUTTERSTOCK

For boys, the usual sequence is growth of the testes, initial pubic-

Unseen Beginnings

Especially for Parents of Teenagers Why would parents blame adolescent moods on hormones?

If something causes adolescents to shout “I hate you,” to slam doors, or to cry inconsolably, parents may decide that hormones are the problem. This makes it easy to dismiss the teenager’s anger. However, research on stress and hormones suggests that this comforting attribution is too simplistic.

Just described are the visible changes of puberty, but the entire process begins with an invisible event—

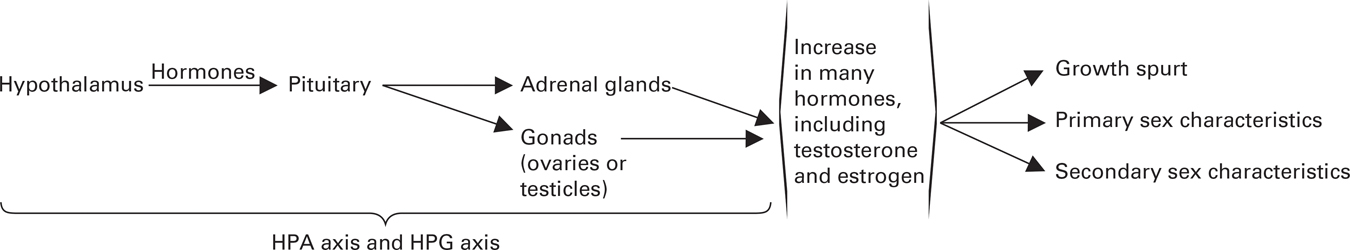

You learned in Chapter 8 that the production of many hormones is regulated deep within the brain, where biochemical signals from the hypothalamus signal another brain structure, the pituitary, to go into action. The pituitary produces hormones that stimulate the adrenal glands, located above the kidneys at either side of the lower back. The adrenal glands produce more hormones.

Many hormones that regulate puberty follow this route, known as the HPA (hypothalamus-

Biological Sequence of Puberty Puberty begins with a hormonal signal from the hypothalamus to the pituitary gland, both deep within the brain. The pituitary, in turn, sends a hormonal message through the bloodstream to the adrenal glands and the gonads to produce more hormones.

Indeed, abnormalities of the HPA axis probably cause the sudden increases in clinical depression among young adolescent girls (Guerry & Hastings, 2011). Further, HPA disruptions are one result of childhood sexual abuse (discussed soon) (Trickett et al., 2011).

Sex Hormones

Late in childhood, the pituitary activates not only the adrenal glands but also the gonads, or sex glands (ovaries in females; testes, or testicles, in males), following another sequence called the HPG (hypothalamus-

Especially for Teenagers Some 14-

No. Early sex has many hazards. Pregnancy is less likely (although quite possible) before age 15. This may lead to a false sense of security, which may disappear with a crash; fertility is higher in the late teens than at any other time. In addition, STIs are especially common with adolescent sex, another reason to use a condom.

Estrogens (including estradiol) are female hormones and androgens (including testosterone) are male hormones, although both sexes have some of both. The biochemical messages from the HPG axis activate the ovaries to produce high levels of estrogens and the testes to produce dramatic increases in androgens. This “surge of hormones” affects bodies, brains, and behavior before any visible signs of puberty appear, “well before the teens” (Peper & Dahl, 2013, p. 134).

The activated gonads produce mature sperm or ova, released in menarche or spermarche. Conception is possible, although fertility peaks several years later.

Hormonal increases and differences may also underlie sex differences in psychopathology. Compared to the other sex, adolescent males are almost twice as likely to develop schizophrenia and adolescent females more than twice as likely to develop depression. Of course, hormones are not the sole cause of psychopathology in anyone (Tackett et al., 2014; Rudolph, 2014).

One psychological effect of hormones at puberty has been proven: Hormones awaken interest in sex. The first sexual objects are usually unattainable—

Emotional surges and lustful impulses may begin with hormones, but remember that body, brain, and behavior always interact. Sexual thoughts themselves can cause physiological and neurological processes, not just result from them.

Cortisol levels rise at puberty, and that makes adolescents quicker to become angry or upset (Goddings et al., 2012; Klein & Romeo, 2013). Then those emotions, in turn, increase levels of various other hormones. Bodies, brains, and behavior each affect the other two.

For example, when other people react to emerging breasts or beards, that evokes thoughts and frustrations in the adolescent, which then raise hormone levels, propel physiological development, and trigger emotions, which then affect people’s reactions. Thus the internal and external changes of puberty each impact the other.

Body Rhythms

The brain of every living creature responds to the environment with natural rhythms that rise and fall by the hours, days, and seasons. For example, body weight and height are affected by time of year: Children’s growth rate increases for height in summer and for weight in winter. Some biorhythms are on a day–

The hypothalamus and the pituitary regulate the hormones that affect patterns of stress, appetite, sleep, and so on. At puberty, these hormones cause a phase delay in the circadian sleep–

For most people, daylight awakens the brain. That’s why people experiencing jet lag are urged to take an early morning walk. The phase delay at puberty makes many teens wide awake and hungry at midnight but half asleep, with no appetite or energy, all morning.

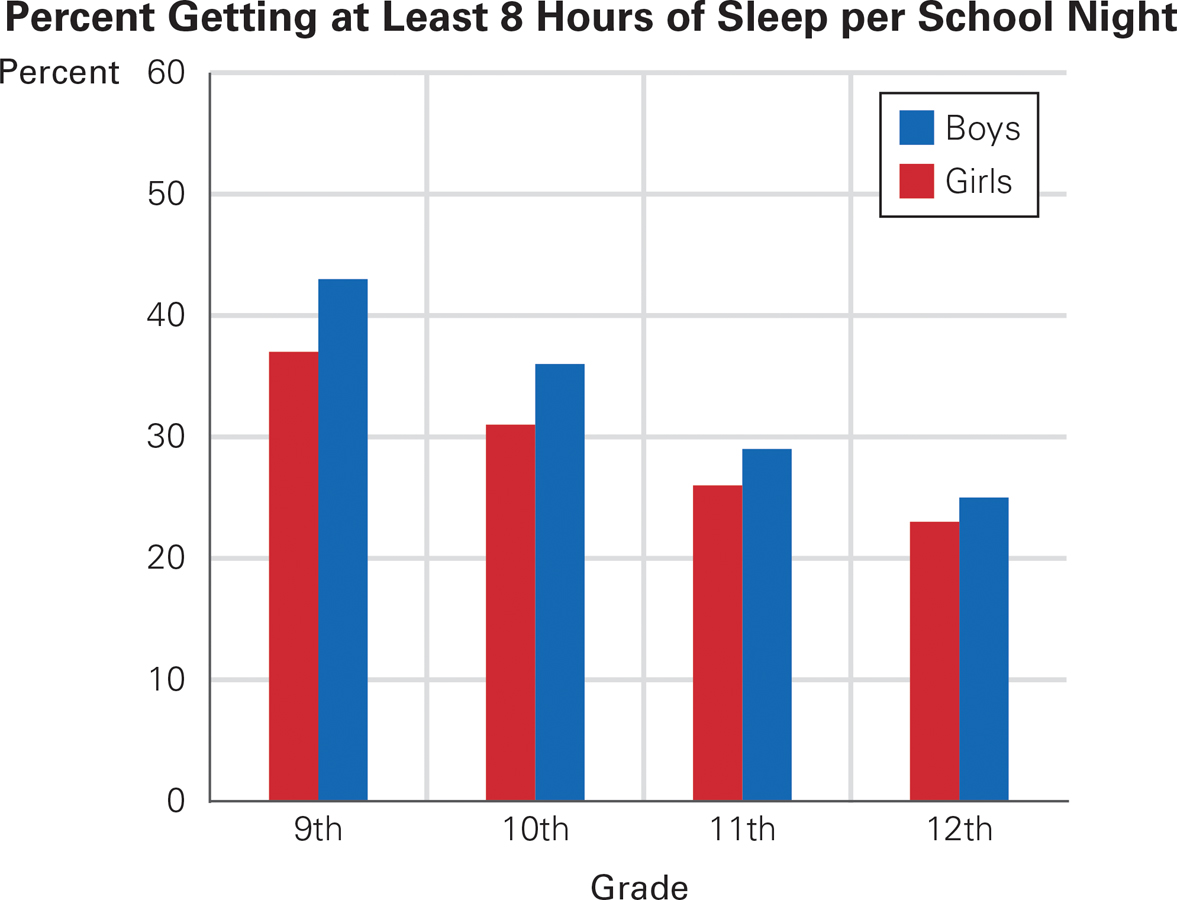

In addition to circadian changes in adolescent bodies, some individuals (especially males) are naturally more alert in the evening than in the morning, a genetic trait called eveningness. Exacerbated by pubertal phase delay, eveningness puts adolescents at risk for antisocial activities because they are awake when adults are asleep. Another result, if school is scheduled for adults, not teenagers, is that students are sleep deprived (Carskadon, 2011). In many nations, sleep deprivation increases during adolescence (see Figure 14.2) (Roenneberg et al., 2012).

Sleepyheads Three of every four high school seniors are sleep deprived. Even if they go to sleep at midnight, as many do, they must get up before 8, as almost all do. Then all day they are tired.

Question 14.1

OBSERVATION QUIZ As you see, girls get even less sleep than boys. Why is that?

Girls tend to spend more time studying, talking to friends, and getting ready in the morning. Other data show that many girls get less than 7 hours of sleep per night.

To make it worse, “the blue spectrum light from TV, computer, and personal-

Sleep deprivation and irregular sleep schedules lead to several specific dangers, including insomnia, nightmares, mood disorders (depression, conduct disorder, anxiety), and falling asleep while driving. In addition, sleepy people do not learn as well as they might when rested. Many adults ignore these facts, as the following Opposing Perspectives explains.

opposing perspectives

Algebra at 7 A.M.? Get Real!

Parents sometimes fight biology. This is evident with sexual curiosity (“you’re too young to think about boys”) and circadian rhythm (“go to sleep, you need to get up at dawn”). Adults set early curfews. For example in 2014, Baltimore implemented a law that requires everyone under age 14 to be home by 9 p.m., and 14-

For many adolescents, however, early sleep and early rising are almost impossible. Sleep-

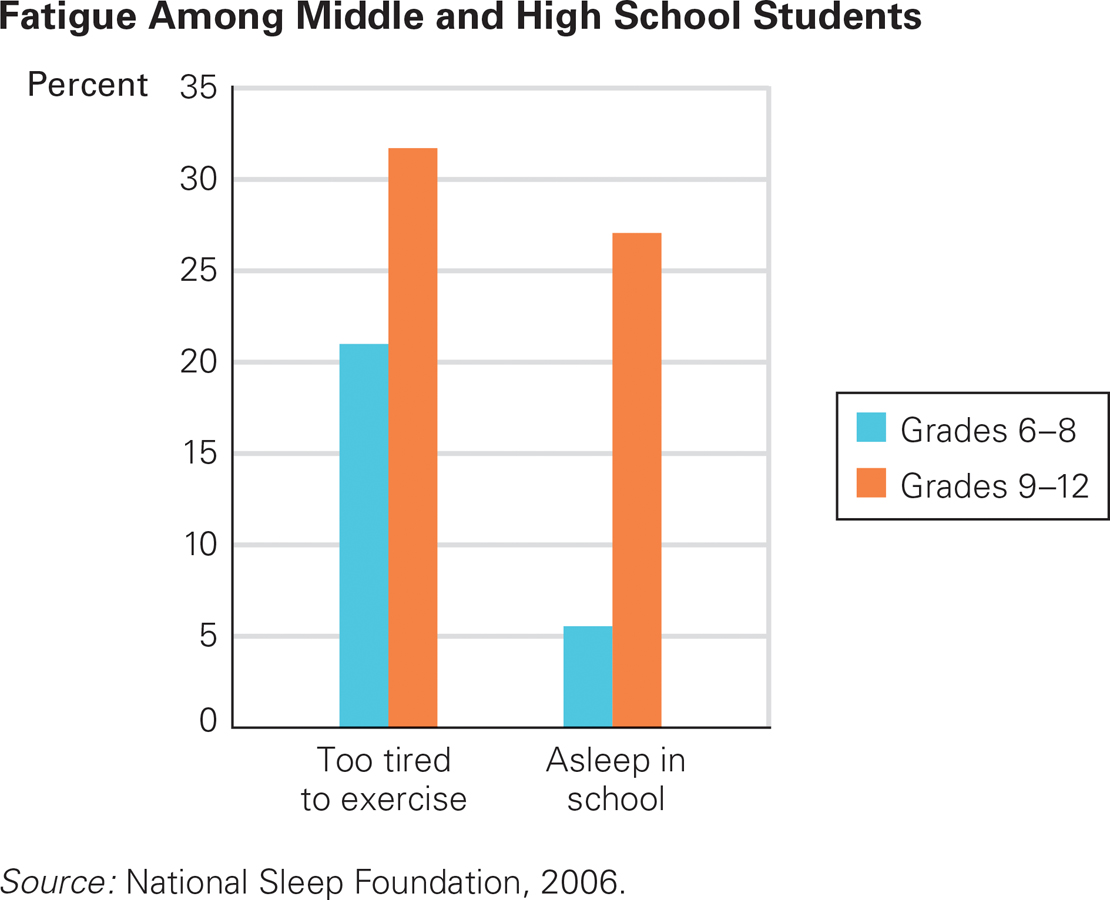

Dreaming and Learning? This graph shows the percentage of U.S. students who, once a week or more, fall asleep in class or are too tired to exercise. Not shown are those who are too tired overall (59 percent of high school students) or who doze in class “almost every day” (8 percent).

Data on circadian rhythm and the teenage brain convinced social scientists at the University of Minnesota to ask 17 school districts to start high school at 8:30 a.m. or later. Parents disagreed. Many (42 percent) thought high school should begin before 8:00 a.m. Some (20 percent) wanted their teenagers out of the house by 7:15 a.m., but only 1 percent of parents with younger children wanted them out by that hour (Wahlstrom, 2002).

Other adults had their own reasons for wanting high school to begin early. Teachers thought that learning was more efficient in the morning; bus drivers hated rush hour; cafeteria workers liked to be done by mid-

Initially only one Minnesota school district (Edina) changed the schedule, from 7:25 a.m.–2:05 p.m. to 8:30 a.m.–3:10 p.m. After a trial year, most parents (93 percent) and virtually all students approved. One student said, “I have only fallen asleep in school once this whole year, and last year I fell asleep about three times a week” (quoted in Wahlstrom, 2002, p. 190). Fewer students were absent, late, disruptive, or sick (the school nurse became an advocate). Grades rose.

Other school districts noticed. Minneapolis high schools changed their start time from 7:15 a.m. to 8:40 a.m. Again, attendance and graduation rates improved.

School boards in South Burlington (Vermont), West Des Moines (Iowa), Tulsa (Oklahoma), Arlington (Virginia), Palo Alto (California), and Milwaukee (Wisconsin) voted to start high school later, from an average of 7:45 a.m. to an average of 8:30 a.m. (Tonn, 2006; Snider, 2012). Unexpected advantages appeared: more efficient energy use, less adolescent depression, and in Tulsa, unprecedented athletic championships.

Many school districts remain stuck to their traditional schedules (set before the hazards of sleep deprivation were known)—scheduling school buses to drop off teenagers at school and then go back to pick up the younger children. Although “the science is there, the will to change is not” (Snider, 2012).

One example comes from Fairfax (Virginia) where two opposing groups: SLEEP (Start Later for Excellence in Education Proposal) versus WAKE (Worried About Keeping Extra-

The later start would hinder teams without lighted practice fields. Hinder kids who work after-

[Williams, 2009]

Note that he never argued that learning in high school would be hindered, because the evidence is that it would not. He wrote that science was on the side of change but reality was not. To developmentalists, of course, science is reality. In 2009, the Fairfax school board voted to keep high school start at 7:20 a.m.

The SLEEP advocates kept trying. On the eighth try, the Fairfax school board in 2012 finally set a goal: High schools should not start before 8 a.m. They hired a team to figure out how to implement that goal. As of 2014, the Fairfax school board had not yet decided on the new start time.

They now have a new reason to change. In August 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics concluded that high school should not begin until 8:30 or 9 a.m., because adolescent sleep deprivation causes a cascade of intellectual and behavioral problems. They noted that 43 percent of high schools in the United States start before 8 a.m. The clash between tradition and science, or between adult expectations and adolescent bodies, continues.

Age and Puberty

Normally, pubertal hormones begin to increase between ages 8 and 14, and visible signs of puberty appear a year later. That six-

Genes and Gender

About two-

The sex chromosomes have a marked effect. In height, the average girl is about two years ahead of the average boy: The female height spurt occurs before menarche, whereas for boys the increase in height is relatively late, after spermarche.

When it comes to hormonal and sexual changes themselves, though, girls may be less than a year ahead of boys. A sixth-

Body Fat

Another major influence on the onset of puberty is body fat. Heavy girls reach menarche years earlier than malnourished ones do. Most girls must weigh at least 100 pounds (45 kilograms) before they experience their first period (Berkey et al., 2000). Although malnutrition always delays puberty, body fat may not be as necessary for well-

Body fat also explains why youths reach puberty at age 15 or later in some parts of Africa, although their genetic relatives in North America mature much earlier. Similarly, malnutrition may explain why puberty began at about age 17 in sixteenth-

Since then, puberty has occurred at younger and younger ages (an example of what is called the secular trend, the trend of changes in human growth as nutrition improved). Increased food availability has led to weight gain in childhood, and that has led to earlier puberty for girls and taller average height for both sexes. Because of the secular trend, for centuries every generation has reached puberty before the previous one (Floud et al., 2011; Fogel & Grotte, 2011).

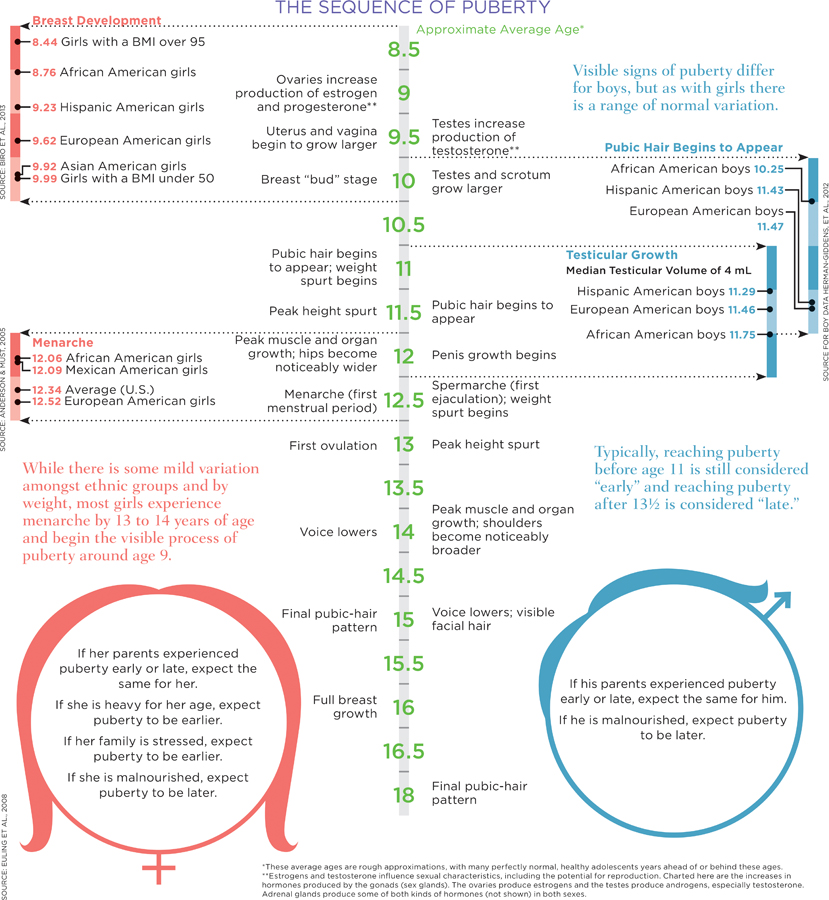

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

The Timing of Puberty

The process of puberty can take years—

Especially for Parents Worried About Early Puberty Suppose your cousin’s 9-

Probably not. If she is overweight, her diet should change, but the hormone hypothesis is speculative. Genes are the main factor; she shares only one-

One curious bit of evidence of the secular trend is that U.S. presidents have been taller in recent decades than they were earlier (James Madison, the fourth president, was shortest at 5 feet, 4 inches; Barack Obama is 6 feet, 1 inch tall). The secular trend seems to have stopped in developed nations, because now nutrition allows everyone to attain their genetic potential. Currently, young men no longer usually look down at their short fathers, or girls at their little mothers, unless the parents were born in Asia or Africa, where the secular trend continues.

Exceptions and Hormones

There is an exception in developed nations to the statement “the secular trend has stopped.” Puberty that begins before age 8, called precocious puberty, seems more common now, although still rare (perhaps 2 percent). The increase may be caused by childhood obesity or by exposure to new chemicals and may be more common in girls than boys.

Some research finds, however, that puberty is delayed, not accelerated, in boys who were exposed to phthalates and bisphenol A when they were in the womb (Ferguson et al., 2014) or who experience heavy doses of pesticides in boyhood (Lam et al., 2014). Another study found that phthalates delay puberty in girls of normal weight, but the authors note that other research has found earlier puberty (Wolff et al., 2014).

Caution, not panic, is needed here. No doubt, heavy doses of many chemicals and pesticides affect fish, frogs, insects, and birds, causing reproductive problems. However, as noted in Chapter 4, experts disagree about the impact on humans of specific environmental toxins, as well as about what dose is safe.

Many researchers focus on sex hormones as factors that accelerate puberty. Of course, estrogens and androgens affect body shape, reproduction, height, and weight, but these sex hormones may also work directly to trigger the onset of puberty, even before visible changes occur.

Many scientists suspect that precocious or delayed puberty is caused by hormones in the food supply, especially in milk. Cattle are fed steroids to increase bulk and milk production, and hundreds of chemicals and hormones are used to produce most of the meat and milk that children consume. All these might affect appetite, body fat, and sex hormones, with effects suspected at puberty (Clayton et al., 2014; Wiley, 2011; Synovitz & Chopak-

Leptin, a hormone naturally produced by the human body, definitely affects the onset of puberty. Leptin affects appetite and energy; without it, puberty does not occur. However, high levels of leptin correlate with obesity. A girl with this problem may experience early puberty that ends relatively soon, stopping growth. Thus the heaviest third-

Normally, body fat produces leptin (one reason puberty is delayed is if a person overexercises or undereats), and starvation increases leptin levels so that the hungry person will seek food. Once weight is gained, higher levels of leptin decrease the appetite (Elias & Purohit, 2013).

Most of the research on leptin has been done with mice; they become fat or thin depending on the levels of this hormone, but the consequences of high or low leptin, especially artificially added, are more complicated for humans than for mice.

In fact, all the research on the effects on humans of hormones and other chemicals, whether natural or artificial, is complex. The precise impact of all the substances in the air, water, or diet on the human sexual-

Stress

Stress hastens the hormonal onset of puberty, especially if a child’s parents are sick, drug-

This is one explanation for the fact that many internationally adopted children experience early puberty, especially if their first few years of life were in an institution or a chaotic home. An alternate explanation is that their age at adoption was underestimated, so puberty appears to occur early but actually occurs at the expected time (Hayes, 2013).

Most developmentalists agree that age of menarche is influenced by genes and experience, as differential susceptibility would predict. Minor stresses—

Twenty years ago many scientists were skeptical about a direct link between stress and puberty. Perhaps early puberty caused stress rather than the other way around? Now, however, the link seems clear. (See A View from Science.)

a view from science

Stress and Puberty

Hypothetically, the connection between stress and early puberty could be indirect. For example, perhaps children in dysfunctional families eat worse and watch TV more, and that makes them overweight. Or perhaps they inherit genes for early puberty from their distressed mothers, and those genes led the mothers to become pregnant too young, creating a stressful family environment.

Either poor nutrition or genetic risk could cause early puberty. Then stress would be an indirect byproduct, not a cause.

However, several longitudinal studies show a direct link between stress and puberty. For example, one longitudinal study of 756 children found parents who demanded respect, often spanked, and rarely hugged their babies were, a decade later, likely to have daughters who reached puberty earlier than other girls in the same study (Belsky et al., 2007). The likely reason: Harsh parenting increases cortisol levels, and cortisol affects puberty.

A follow-

Why would higher cortisol trigger puberty? The opposite effect—

Maturing quickly and breeding promiscuously would enhance reproductive fitness more than would delaying development, mating cautiously, and investing heavily in parenting. The latter strategy, in contrast, would make biological sense, for virtually the same reproductive-

[Belsky et al., 2010, p. 121]

In other words, thousands of years ago, when harsh conditions threatened survival of the species, adolescents needed to reproduce early and often. Natural selection would hasten puberty to increase the birth rate.

By contrast, in peaceful times with plentiful food, puberty could occur later, allowing children to postpone maturity and instead enjoy extra years of nurturance from parents and grandparents. Genes evolved to respond differently to war and peace.

Of course, this evolutionary rationale no longer applies. Today, early sexual activity and reproduction are more likely to destruct than protect communities.

However, the genome has been shaped over millennia; if there is a puberty-

Too Early, Too Late

For most adolescents, these links between puberty, genes, fat, stress, and hormones are irrelevant. Only one aspect of timing matters: their friends’ schedules. No one wants to be too early or too late.

Girls

Think about the early-

Question 14.2

OBSERVATION QUIZ Who is least developed and who is most?

Impossible to be sure, but it seems as if the only one smiling is the least developed (note the size of her hands, the narrowness of her hips, and her height); the one on the left is the most developed (note hips, facial expression, height, and—

Sometimes early-

Boys

Research over the past 100 years has always found that early female maturation is more often harmful than helpful, but cohort seems crucial for males. Early-

In the twenty-

Early puberty is particularly stressful if it happens suddenly: The boys most likely to become depressed are those for whom puberty was both early and quick (Mendle et al., 2010). In adolescence, depression is often masked as anger. That fuming, flailing 12-

Late puberty may also be difficult, especially for boys (Benoit et al., 2013). Slow-

Every adolescent wants to hit puberty “on time.” They often overestimate or underestimate their maturation, or become depressed, if they are not average (Conley & Rudolph, 2009; Shirtcliff et al., 2009; Benoit et al., 2013). These effects are not caused by biology alone; family contexts and especially peer pressure can make early and late puberty worse (Mendle et al., 2012; Benoit et al., 2013).

Ethnic Differences

Puberty that is late by world norms, at age 14 or so, is not troubling if one’s friends are late as well. Well-

For adolescents of all ethnic backgrounds, peer approval is more important than adult approval or historic understanding. The effects of early puberty vary not only by sex but also by ethnicity and culture. For instance, one study found that, in contrast to European Americans, early-

European research finds that Swedish early-

None of these trends is true for all children, of course, as ethnicity is only one influence on development. However, all three studies confirm that contextual factors interact with biological ones, and both have significant implications for individuals. Always, relationships with peers and parents make off-

SUMMING UP Puberty usually begins between ages 8 and 14 (typically around age 11) in response to a chain reaction of hormones from the hypothalamus, to the pituitary, to the adrenal and sex glands.

Hormones interact with emotions: Adolescent outbursts of sudden anger, sadness, and lust are affected both by hormones and by reactions from other people to the young person’s changing body. The dynamic interaction among hormones, genes, adolescent behavior, and social regulations is evident in the clash between circadian rhythm and high school schedules. Many teenagers are sleep deprived, which affects their learning and emotions.

Genes, body fat, hormones, and stress affect the onset of puberty, especially among girls. For both sexes, early or late puberty is less desirable than puberty at the same age as one’s peers; off-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 14.3

What are the first visible signs of puberty?

For girls, the observable changes of puberty usually begin with nipple growth. Soon a few pubic hairs are visible, then peak growth spurt, widening of the hips, the first menstrual period (menarche), full pubic–hair pattern, and breast maturation. For boys, the usual sequence is growth of the testes, initial pubic– hair growth, growth of the penis, first ejaculation of seminal fluid, appearance of facial hair, peak growth spurt, deepening of the voice, and final pubic– hair growth. Question 14.4

What body parts of a teenage boy or girl are the last to reach full growth?

Height, weight, and muscle continue to grow until approximately age 20, especially for boys. A final pubic hair pattern in boys and full breast growth in girls are the last to develop.Question 14.5

How do hormones affect the physical and psychological aspects of puberty?

In girls, estrogen triggers menarche and may contribute to depression. In boys, androgens produce sperm and trigger spermarche, and, in a small number of boys, may also contribute to the onset of schizophrenia. In both boys and girls, hormones awaken their interest in sex.Question 14.6

Why do adolescents experience sudden, intense emotions?

Not only are the brain and the body affected by hormones, but behavior is as well. Surges of emotions and sudden lustful impulses are partly hormonal, but thoughts can cause physiological and neurological processes, as well as result from them. The hormones of puberty make young adolescents more vulnerable to stress, and thus quicker to become angry or upset. Those emotions can increase hormone levels.Question 14.7

How does the circadian rhythm affect adolescents?

Some biorhythms are on a day–night cycle that occurs approximately every 24 hours, called the circadian rhythm. Puberty affects biorhythms. The hypothalamus and the pituitary regulate the hormones that affect patterns of stress, appetite, sleep, and so on. At puberty, these hormones cause a phase delay in the circadian sleep– wake cycles. The delay is in the body's reaction to daylight and dark. For most people, daylight awakens the brain. That's why people experiencing jet lag are urged to take an early morning walk. The phase delay at puberty makes many teens wide awake and hungry at midnight but half asleep, with no appetite or energy, all morning. Question 14.8

What are the consequences of sleep deprivation?

Sleep deprivation and irregular sleep schedules lead to several specific dangers, including insomnia, nightmares, mood disorders (depression, conduct disorder, anxiety), and falling asleep while driving. In addition, sleepy people do not learn as well as they might when rested.Question 14.9

What are the gender differences in the growth spurt?

Girls experience their height growth spurt an average of two years before boys do. Girls' height growth spurt usually precedes menarche, whereas boys' height growth spurt usually follows spermarche.Question 14.10

What are the ethnic and cultural differences in the timing of puberty?

According to research, about two–thirds of the variation in age of puberty is genetic, which is evident across cultures. While an entire group may reach puberty sooner or later than North American children, the differences between boys and girls, with girls maturing faster, is evidenced across cultures. Body fat, socioeconomic status, living in an urban environment, and stress all play a role in onset. Question 14.11

How does off-

time puberty affect girls? Early–maturing girls tend to have lower self– esteem, more depression, and poorer body image than do other girls. Because boys mature on average two years later than girls, they may tease an early– developing girl due to being unnerved by a sexual creature in their midst. Early– maturing girls also have more difficulties with self– image, tend to have older boyfriends, and are more susceptible to drug and alcohol abuse and domestic violence. Question 14.12

How does off-

time puberty affect boys? In the twenty–first century, early– maturing boys are more aggressive, lawbreaking, and alcohol– abusing than the average boy. Late developing boys tend to be more anxious, depressed, and afraid of sex. Girls are less attracted to them, and coaches less often want them on their teams.