Growth and Nutrition

Puberty entails transformation of every part of the body, each change affecting the others. Here we discuss biological growth, the nutrition that fuels that growth, and the eating disorders that disrupt it. Next we will focus on the two other aspects of pubertal transformation, brain reorganization and sexual maturation.

Growing Bigger and Stronger

The first set of changes is called the growth spurt—a sudden, uneven jump in the size of almost every body part, turning children into adults. Growth proceeds from the extremities to the core (the opposite of the earlier proximodistal growth). Thus, fingers and toes lengthen before hands and feet, hands and feet before arms and legs, arms and legs before the torso. This growth is not always symmetrical: One foot, one breast, or even one ear may grow later than the other.

Because the torso is the last body part to grow, many pubescent children are temporarily big-

Sequence: Weight, Height, Muscles

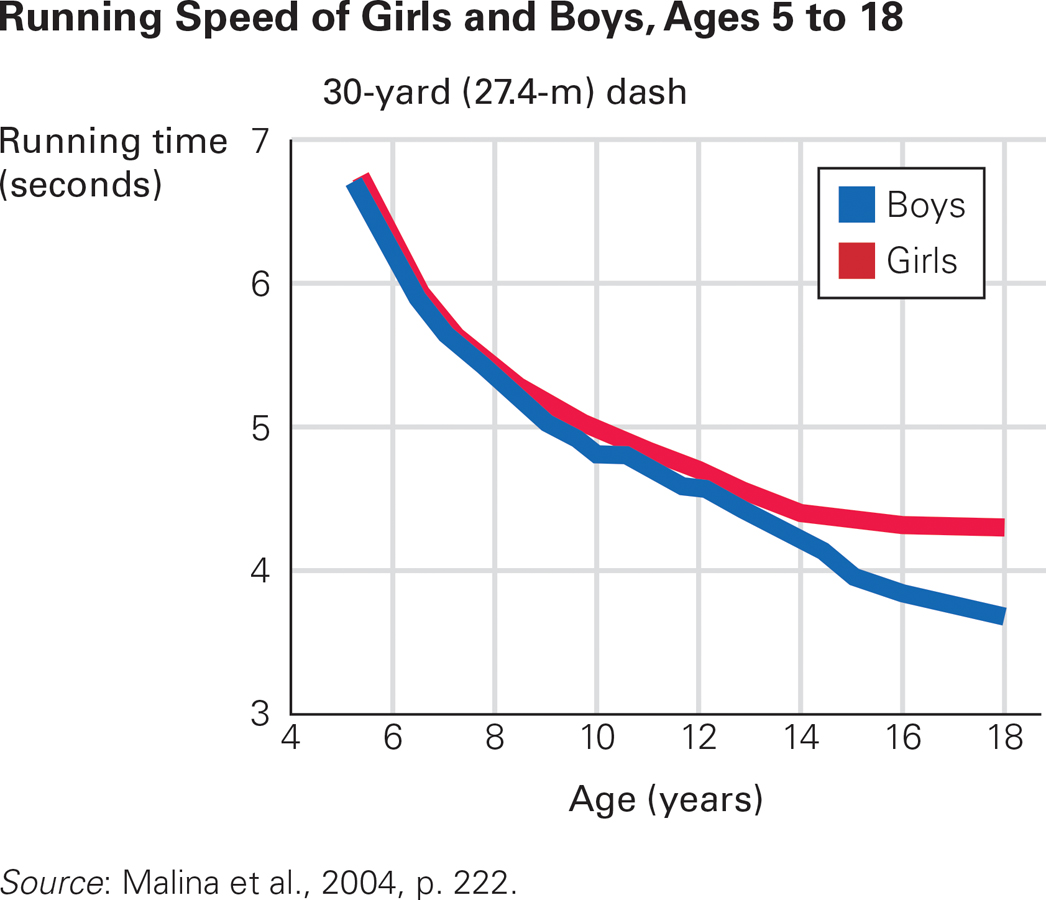

Little Difference Both sexes develop longer and stronger legs during puberty, but eventually, females are somewhat slower than males.

As the growth spurt begins, children eat more and gain weight. Exactly when, where, and how much weight they gain depends on heredity, hormones, diet, exercise, and gender. By age 17, the average girl has twice the percentage of body fat as her male classmate, whose increased weight is mostly muscle.

A height spurt follows the weight spurt; then a year or two later a muscle spurt occurs. Thus, the pudginess and clumsiness of early puberty are usually gone by late adolescence. Keep in mind, however, that puberty may dislodge the usual relationship between height and overweight or underweight. A child may be eating too much or too little for their height, but that may not be apparent in conventional measures of BMI (Golden et al., 2012).

At puberty, all the muscles increase in power. Arm muscles develop particularly in boys, doubling in strength from age 8 to 18. Other muscles are gender neutral. Both sexes run faster with each year of adolescence, with boys not much faster than girls (unless the girls choose to slow down) until the end of high school (see Figure 14.4).

Organ Growth

In both sexes, organs mature in much the same way. Lungs triple in weight; consequently, adolescents breathe more deeply and slowly. The heart (another muscle) doubles in size as the heartbeat slows, decreasing the pulse rate while increasing blood pressure (Malina et al., 2004). Consequently, endurance improves: Some teenagers can run for miles or dance for hours. Red blood cells increase in both sexes, but dramatically more so in boys, which aids oxygen transport during intense exercise.

Both weight and height increase before muscles and internal organs: To protect immature muscles and organs, athletic training and weight lifting should be tailored to an adolescent’s size the previous year. Sports injuries are the most common school accidents, and they increase at puberty. One reason is that the height spurt precedes increases in bone mass, making young adolescents particularly vulnerable to fractures (Mathison & Agrawal, 2010).

One organ system, the lymphoid system (which includes the tonsils and adenoids), decreases in size, so teenagers are less susceptible to respiratory ailments. Mild asthma, for example, often switches off at puberty—

Another organ system, the skin, becomes oilier, sweatier, and more prone to acne. Hair also changes, becoming coarser and darker. New hair grows under arms, on faces, and over sex organs (pubic hair, from the same Latin root as puberty). Visible facial and chest hair is sometimes considered a sign of manliness, although hairiness in either sex depends on genes as well as on hormones.

Girls pluck or wax any facial hair they see and shave their legs, while boys proudly grow sideburns, soul patches, chinstraps, moustaches, and so on—

Often teenagers cut, style, or grow their hair in ways their parents do not like, as a sign of independence. To become more attractive, many adolescents spend considerable time, money, and thought on their visible hair—

Diet Deficiencies

All the changes of puberty depend on adequate nourishment, yet many adolescents do not eat well. Teenagers often skip breakfast, binge at midnight, guzzle down unhealthy energy drinks, and munch on salty, processed snacks. One reason for their eating patterns is that their hormones affect the circadian rhythm of their appetites; another reason is that their drive for independence makes them avoid family dinners, refusing to eat what their mothers say they should. Family dinners in supportive families correlate with healthy adolescent eating and well-

Cohort and age are crucial. In the United States, each new generation eats less well than the previous one, and each 18-

Deficiencies of iron, calcium, zinc, and other minerals are especially common during adolescence. Because menstruation depletes iron, anemia is more likely among adolescent girls than among any other age group. This is true everywhere, especially in South Asia and sub-

Reliable laboratory analysis of blood iron on a large sample of young girls in developing nations is not available, but all indications suggest that many are anemic. Data is available for 18-

Boys everywhere may also be iron-

Similarly, although the daily recommended intake of calcium for teenagers is 1,300 milligrams, the average U.S. teen consumes less than 500 milligrams a day. About half of adult bone mass is acquired from ages 10 to 20, which means many contemporary teenagers will develop osteoporosis (fragile bones), a major cause of disability, injury, and death in late adulthood, especially for women.

One reason for calcium deficiency is that milk drinking has declined. In 1961, most North American children drank at least 24 ounces (about three-

Choices Made

Many economists advocate a “nudge” to encourage people to make better choices, not only in nutrition but also in all other aspects of their lives (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). Teenagers are often nudged in the wrong direction. Nutritional deficiencies result from the food choices that young adolescents are enticed to make.

Fast-

Price influences food choices, especially for adolescents, and healthy fast foods cost more than unhealthy ones. For example, compare the prices of a McDonald’s salad and a hamburger.

Nutritional deficiencies increase when schools have vending machines that offer soda and snacks, especially for middle school students (Rovner et al., 2011). An increasing number of laws require schools to encourage healthy eating, but effects are more apparent in elementary schools than high schools (Mâsse et al., 2013; Terry-

Many adolescents spurn school lunches in favor of unhealthy snacks sold by in-

Rates of obesity are falling in childhood but not in adolescence. Only three U.S. states (Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee) had high-

Body Image

One reason for poor nutrition among teenagers is anxiety about body image—that is, a person’s idea of how his or her body looks. Few teenagers welcome every change in their bodies. Instead, they tend to focus on and exaggerate imperfections (as did the three girls in the anecdote that opens this chapter). Two-

Few adolescents are happy with their bodies, partly because almost none look like the bodies portrayed online and in magazines, movies, and television programs that are marketed to teenagers (Bell & Dittmar, 2011). Unhappiness with appearance—

Eating Disorders

Video Activity: Eating Disorders introduces the three main types of eating disorders and outlines the signs and symptoms of each.

Dissatisfaction with body image can be dangerous, even deadly. Many teenagers, mostly girls, eat erratically or ingest drugs (especially diet pills) to lose weight; others, mostly boys, take steroids to increase muscle mass. (Developmental Link: Teenage drug abuse is discussed in Chapter 16.) Eating disorders are rare in childhood but increase dramatically at puberty, accompanied by distorted body image, food obsession, and depression (Le Grange & Lock, 2011). Such disorders are often unrecognized until they get worse in emerging adulthood.

Adolescents sometimes switch from obsessive dieting, to overeating, to overexercising, and back again. Obesity is an eating disorder at every age. (Developmental Link: Obesity is discussed in Chapter 8 and in the epilogue.) Here we describe three other eating disorders likely to begin in adolescence.

Anorexia Nervosa

A body mass index (BMI) of 17 or lower, or loss of more than 10 percent of body weight within a month or two, indicates anorexia nervosa, a disorder characterized by voluntary starvation and a destructive and distorted attitude about one’s own body fat. The affected person becomes very thin, risking death by organ failure. Staying too thin becomes an obsession.

Although anorexia existed earlier, it was not identified until about 1950, when some high-

Certain alleles increase the risk of developing anorexia (Young, 2010), with higher risk among girls with close relatives who suffer from eating disorders or severe depression. Although far more common in girls, boys are also at risk.

Bulimia Nervosa and Binge Eating Disorder

About three times as common as anorexia is bulimia nervosa (also called binge–

Binging and purging are common among adolescents. For instance, a survey found that in the last 30 days of 2013, 6.6 percent of U.S. high-

A disorder newly recognized in DSM-

All adolescents are vulnerable to unhealthy eating. Autonomy and body image can lead to disorders. Teenagers try new diets, go without food for 24 hours (as did 19 percent of U.S. high-

Parents are slow to recognize eating disorders, and delay getting help that their children need (Thomson et al., 2014). Yet the research on all the eating disorders finds that family function (not structure) is crucial (Tetzlaff & Hilbert, 2014).

A combination of causes leads to obesity, anorexia, bulimia, or bingeing. At least five general elements—

A developmental perspective notes that healthy eating begins with childhood habits and family routines. Most overweight or underweight newborns never develop nutritional problems, but children who are overweight or underweight are at risk. Particularly in adolescence, family-

SUMMING UP The transformations of puberty are dramatic. Boys and girls become men or women, both physically and neurologically, although full maturity takes a decade or so. Growth proceeds from the extremities to the center, so the limbs grow before the internal organs do. Increase in weight precedes that in height, which precedes growth of the muscles and of the internal organs.

All adolescents are vulnerable to poor nutrition; few are well nourished day after day, year after year. Insufficient iron and calcium is particularly common as fast food and nutrient-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 14.13

What is the pattern of growth in adolescent bodies?

Growth proceeds from the extremities to the core. Thus, fingers and toes lengthen before hands and feet, hands and feet before arms and legs, arms and legs before the torso. This can cause a teen to be awkward and clumsy. To complicate matters further, growth is not always even.Question 14.14

What complications result from the sequence of growth (weight/height/muscles)?

Since bones typically grow faster than muscles and internal organs, adolescents are more prone to athletic injuries in adolescence than when they were younger, and can also move with greater awkwardness and clumsiness due to rapid but often uneven growth. Weight lifting can be dangerous because muscles are not mature.Question 14.15

Why are many adolescents unhappy with their appearance?

Few teenagers welcome every change puberty causes in their bodies. Instead, they tend to focus on and exaggerate imperfections. Few adolescents are happy with their bodies, partly because almost none look like the bodies portrayed in the media.Question 14.16

What interferes with the ability of adolescents to get enough iron and calcium?

Many adolescents do not eat well. Teenagers often skip breakfast, binge at midnight, guzzle down unhealthy energy drinks, and munch on salty, processed snacks. In girls, menstruation depletes iron. Boys everywhere may also be iron–deficient if they engage in physical labor or intensive sports. In developed as well as developing nations, many adolescents of both sexes spurn iron– rich foods (green vegetables, eggs, and meat) in favor of iron– poor chips, sweets, and fries.

One reason for calcium deficiency is that milk drinking has declined. In 1961, most North American children drank at least 24 ounces (about three–fourths of a liter) of milk each day, providing almost all (about 900 milligrams) of their daily calcium requirement. Fifty years later, only 12.5 percent of high school students drank that much milk and 19 percent (more girls than boys) drank no milk at all. Question 14.17

Why would anyone voluntarily starve to death?

People suffering from anorexia nervosa refuse to eat normally because their body image is severely distorted; they may believe they are too fat when actually they are dangerously underweight.Question 14.18

Why would anyone make herself or himself throw up?

Individuals with bulimia make themselves vomit after consuming thousands of calories in order to control their weight.