Logic and Self

Brain maturation, additional years of schooling, moral challenges, increased independence, and intense conversations all occur between the ages of 11 and 18. These aspects of adolescents’ development propel impressive cognitive growth, as teenagers move from egocentrism to abstract logic.

Egocentrism

During puberty, young people center on themselves, in part because maturation of the brain heightens self-

Adolescent egocentrism—that is, adolescents thinking intensely about themselves and about what others think of them—

Now in the 8th grade, Edgar has this idea that all the girls are looking at him in school. He got his first pimple about three months ago. I told him to wash it with my face soap but he refused, saying, “Not until I go to school to show it off.” He called the dentist, begging him to approve his braces now instead of waiting for a year. The perfect gifts for him have changed from action figures to a bottle of cologne, a chain, and a fitted baseball hat like the rappers wear.

[adapted from Eva, personal communication]

Egocentrism leads adolescents to interpret everyone else’s behavior as if it were a judgment on them. A stranger’s frown or a teacher’s critique can make a teenager conclude that “No one likes me” and then deduce that “I am unlovable” or even “I can’t leave the house.” More positive casual reactions—

Acute self-

Because adolescents focus on their own perspectives, oblivious to other viewpoints, their emotions may not be grounded in reality. For example, a study of 1,310 Dutch and Belgian adolescents found that egocentrism was strong, and self-

Fables

The personal fable is the belief that one is unique, destined to have a heroic, fabled, even legendary life. Some 12-

Adolescents markedly overestimate the chance that they will die soon. One study found that teens estimate 1 chance in 5 that they will die before age 20, when in fact the odds are less than 1 in 1,000. Even those most at risk of early death (urban African American males) survive at least to age 20 more than 99 times in 100. But if the peer group thinks that some of them will die young, they are more likely to do self-

The personal fable may coexist with the invincibility fable, the idea that death will not occur unless it is destined, which is another reason that some adolescents believe that fast driving, unprotected sex, or addictive drugs will do them no harm unless “their number is up.”

In every nation, most army volunteers—

The Imaginary Audience

Egocentrism creates an imaginary audience in the minds of many adolescents. They believe they are at center stage, with all eyes on them, and they imagine how others might react to their appearance and behavior.

One woman remembers:

When I was 14 and in the 8th grade, I received an award at the end-

[Somerville, 2013, p. 121]

This woman went on to become an expert on the adolescent brain. She remembered from personal experience that “adolescents are hyperaware of other’s evaluations and feel they are under constant scrutiny by an imaginary audience” (Somerville, 2013, p. 124).

A librarian acknowledges that libraries are rule-

Another venue where the imaginary audience dominates is online. Teens post comments on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and so on, and they expect others to understand, laugh, or sympathize. Their imaginary audience is their friends and other teenagers, not parents, teachers, college admission officers, or future employers who might have another interpretation (boyd, 2014).

Too much can be made of adolescent egocentrism. Indeed, one team of researchers considers adolescent egocentrism a “largely discredited notion” (Laursen & Hartl, 2013, p. 1266). Nonetheless, they and many others find some truth in it. Adults must not exaggerate the idea or blame every adolescent behavior on it, but understanding egocentrism may help understanding adolescence.

Formal Operational Thought

Piaget described a shift to formal operational thought as adolescents move past concrete operational thinking and consider abstractions, including “assumptions that have no necessary relation to reality” (Piaget, 1972, p. 148).

Is Piaget correct? Many educators think so. They adjust the curriculum between primary and secondary school, reflecting a shift from concrete to formal, logical thought. Here are three examples:

Math. Younger children multiply real numbers, such as 4 × 3 × 8; adolescents can multiply unreal numbers, such as (2x)(3y) or even (25xy2)(−3zy3).

Social studies. Younger children study other cultures by considering daily life—

drinking goat’s milk or building an igloo, for instance. Adolescents consider the effect of GNP (gross national product) and TFR (total fertility rate) on global politics. They ponder the relationship between the Egyptian Spring and the size of the young adult cohort, for instance. Science. Younger students water plants; adolescents test H2O in the lab and learn about invisible molecules and distant galaxies.

Piaget’s Experiments

Piaget and his colleagues devised a number of tasks to assess formal operational thought (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958). In these tasks, “in contrast to concrete operational children, formal operational adolescents imagine all possible determinants … [and] systematically vary the factors one by one, observe the results correctly, keep track of the results, and draw the appropriate conclusions” (P. H. Miller, 2011, p. 57).

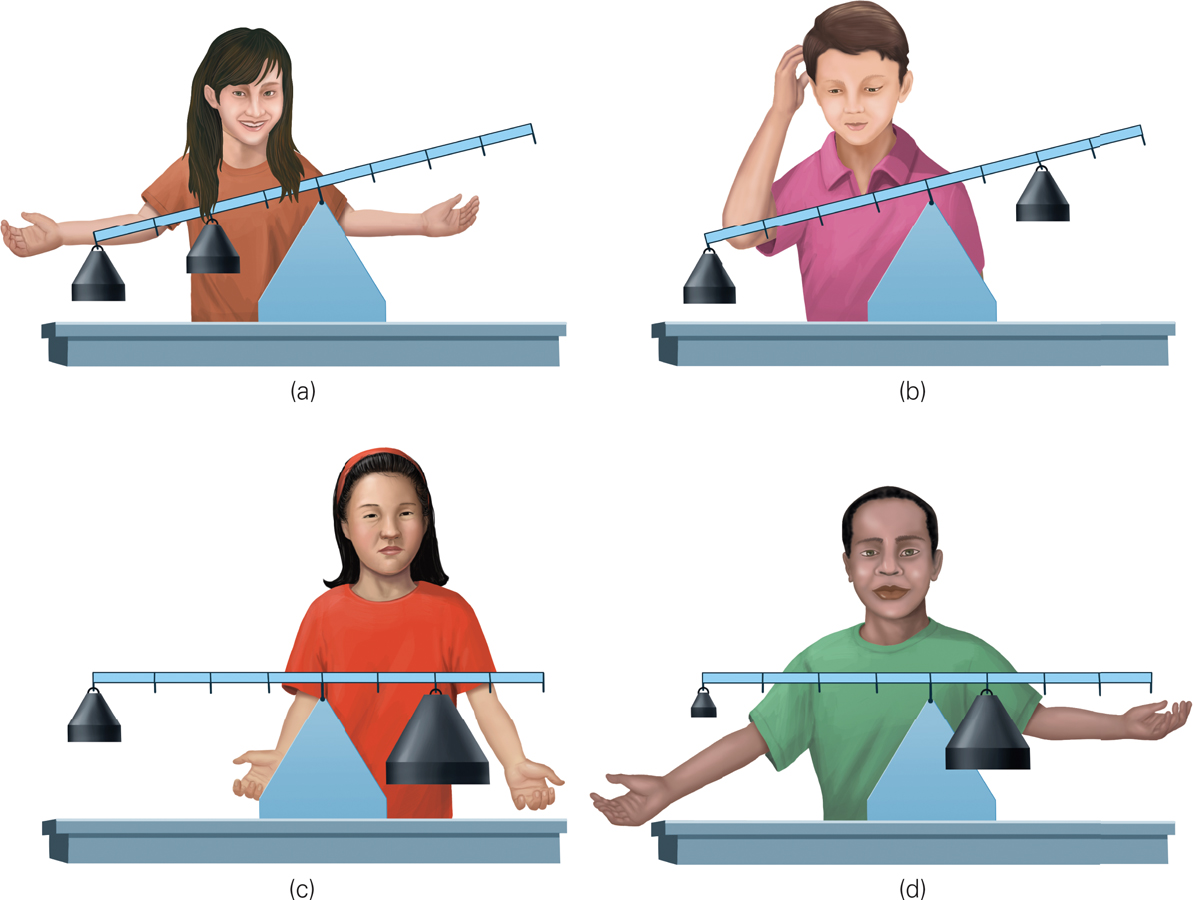

One of their experiments (diagrammed in Figure 15.1) required balancing a scale by hooking weights onto the scale’s arms. To master this task, a person must realize the reciprocal interaction between distance from the center and heaviness of the weight. Therefore, a heavy weight close to the center can be counterbalanced with a light weight far from the center on the other side.

How to Balance a Scale Piaget’s balance-

Balancing was not understood by the 3-

Hypothetical-Deductive Reasoning

One hallmark of formal operational thought is the capacity to think of possibility, not just reality. “Here and now” is only one of many possibilities, including “there and then,” “long, long ago,” “not yet,” and “never.” As Piaget said:

The adolescent … thinks beyond the present and forms theories about everything, delighting especially in considerations of that which is not….

[Piaget, 1972, p. 148]

Adolescents are therefore primed to engage in hypothetical thought, reasoning about if–

If all mammals can walk,

And whales are mammals,

Can whales walk?

Children answer “No!” They know that whales swim, not walk; the logic escapes them. Some adolescents answer “Yes.” They understand the conditional if, and therefore the counterfactual phrase “if all mammals.”

Possibility no longer appears merely as an extension of an empirical situation or of action actually performed. Instead, it is reality that is now secondary to possibility.

[Inhelder & Piaget, 1958, p. 251; emphasis in original]

Hypothetical thought transforms perceptions, not necessarily for the better. Zombies and robots become fascinating, sometimes frightening.

Adolescents criticize everything from their mother’s spaghetti (it’s not al dente) to the Gregorian calendar (it’s not the Chinese or Jewish one). They criticize what is because of their hypothetical thinking and their awareness of other families and cultures. That complicates immediate, practical decisions (Moshman,2011).

In developing the capacity to think hypothetically, by age 14 or so adolescents become more capable of deductive reasoning, or top-

In essence, a child’s reasoning goes like this: “This creature waddles and quacks. Ducks waddle and quack. Therefore, this must be a duck.” This is inductive: It progresses from particulars (“waddles” and “quacks”) to a general conclusion (“a duck”). By contrast, deduction progresses from the general to the specific: “If it’s a duck, it will waddle and quack” (see Figure 15.2).

Bottom Up or Top Down? Children, as concrete operational thinkers, are likely to draw conclusions on the basis of their own experiences and what they have been told. This is called inductive, or bottom-

Especially for Natural Scientists Some ideas that were once universally accepted, such as the belief that the sun moved around the Earth, have been disproved. Is it a failure of inductive or deductive reasoning that leads to false conclusions?

Probably both. Our false assumptions are not logically tested because we do not realize that they might need testing.

An example of the progress toward deductive reasoning comes from how children, adolescents, and adults change in their understanding of the causes of racism. Even before adolescence, almost everyone is aware that racism exists—

Using inductive reasoning, children conclude that the remedy is education. They argue against racism when they hear other people express it. By contrast, older adolescents think, deductively, that racism is a society-

This example arises from a study of adolescent opinions regarding policies to remedy racial discrimination (Hughes & Bigler, 2011). Not surprisingly, most students of all ages in an interracial U.S. high school recognized disparities between African and European Americans and believed that racism was a major cause.

However, the age of the students made a difference. Among those who recognized marked inequalities, older adolescents (ages 16 to 17) more often supported systemic solutions (e.g., affirmative action and desegregation) than did younger adolescents (ages 14 to 15). Hughes and Bigler wrote: “[D]uring adolescence, cognitive development facilitates the understanding that discrimination exists at the social-

Logical Fallacies

Many cognitive scientists study how people of all ages sometimes think illogically. Such failures are apparent throughout adolescence (Albert & Steinberg, 2011), but there is one age-

One example is the sunk cost fallacy: When people have spent money, time, or effort that cannot be recovered (a cost already “sunk”), they hold the fallacy that they must continue to pursue their goal because otherwise all previous effort will have been wasted (Cunha & Caldieraro, 2009). This fallacy leads people to pour money into repairing a “lemon” of a car, to remain in a class they are failing, to stay in an abusive relationship, and so on.

Another common fallacy is base rate neglect, in which people ignore information about the frequency of a phenomenon. For example (cited by Kahneman, 2011, p. 151), if a stranger on the subway is reading the New York Times, which is more likely?

She does not have a college degree.

She has a PhD.

The answer is no college degree. Far more subway riders have no degree than have a PhD (perhaps 50:1). But people tend to ignore that base rate, and instead conclude that a PhD recipient is more likely to read the New York Times than someone without a degree. That is base rate neglect.

Egocentrism makes base rate neglect more likely and more personal. For instance, a teen might not wear a bicycle helmet, feeling invincible despite statistics, until a friend is brain-

Many have criticized Piaget’s stage theory, as you know from previous chapters. That is apparent regarding formal operational thinking as well. For instance, research has found that adults long past adolescence sometimes reason like concrete operational or even preoperational children. Logical fallacies occur at every age, and “No contemporary scholarly reviewer of research evidence endorses the emergence of a discrete new cognitive structure at adolescence that closely resembles … formal operations” (Kuhn & Franklin, 2006, p. 954).

Nonetheless, something shifts in cognition after puberty: Piaget was correct when he concluded that most older adolescents possess the ability to think more logically and hypothetically than most children do.

SUMMING UP Thinking reaches heightened self-

Piaget’s formal operational thought, which includes his fourth and final stages of intelligence, begins in adolescence. He found that adolescents’ deductive logic and hypothetical reasoning improve. That is reflected in the curricula of high schools as well as the adolescent’s readiness to argue with adults. Other scholars note logical lapses at every age and much more variability in adolescent thought than Piaget’s description implies.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 15.1

How does adolescent egocentrism differ from early-

childhood egocentrism? In early childhood, egocentrism refers to the inability to take another person's perspective. Young adolescents not only think intensely about themselves but also think about what others think of them. Adolescents regard themselves as unique, special, and much more socially significant than they actually are.Question 15.2

What perceptions arise from belief in the imaginary audience?

Adolescents believe that everyone is watching them, which makes them very self–conscious. They may become shy and awkward or try to fade into the background so no one notices them. Others may seek to be the center of attention and do things to draw attention to themselves. Question 15.3

Why are the personal fable and the invincibility fable called “fables”?

They are both significant cognitive distortions of reality in which teens are never harmed by dangerous activities or risky behaviors.Question 15.4

What are the practical implications of adolescent cognition?

Changes in adolescent cognition lead to some distorted perceptions of the self, as is evidenced in the reemergence of egocentrism, the personal and invincibility fable, and the imaginary audience. However, advances in cognition also lead to more systematic logical thinking and the ability to understand and manipulate abstract concepts.Question 15.5

What are the advantages and disadvantages of using inductive rather than deductive reasoning?

The advantage of inductive reasoning is that it is quick and automatic. The disadvantage is that it is more prone to error than deductive reasoning.Question 15.6

What objections are raised by contemporary scholars to Piaget’s description of adolescent cognition?

Many have criticized Piaget's stage theory. That is apparent regarding formal operational thinking as well. For instance, research has found that adults long past adolescence sometimes reason like concrete operational or even preoperational children. Logical fallacies occur at every age, and “No contemporary scholarly reviewer of research evidence endorses the emergence of a discrete new cognitive structure at adolescence that closely resembles. . . formal operations.”