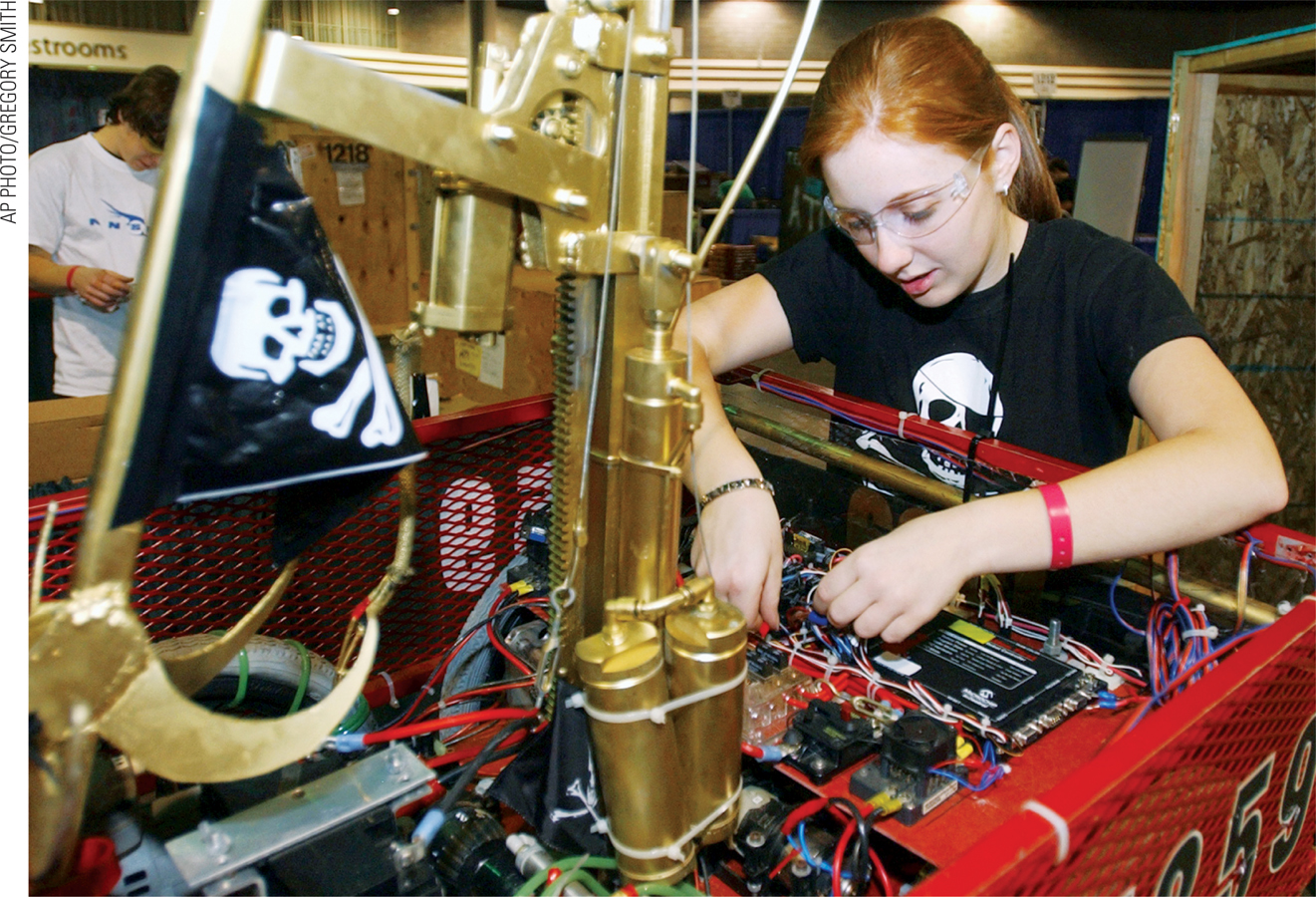

Two Modes of Thinking

Advanced logic in adolescence is counterbalanced by the increasing power of intuitive thinking. A dual-

Intuition Versus Analysis

Most cognitive psychologists recognize two modes of thought, using various terms and descriptions to describe them. The terms include: intuitive/analytic, implicit/explicit, creative/factual, contextualized/decontextualized, unconscious/conscious, gist/quantitative, emotional/intellectual, experiential/rational, hot/cold, systems 1 and 2. Here we refer to them as intuitive and analytical. Although they interact and can overlap, each mode is independent (Kuhn, 2013).

The thinking described by the first half of each pair is easier and quicker, preferred in everyday life. Sometimes, however, circumstances necessitate the second mode, when more careful thought is demanded. The discrepancy between the maturation of the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex reflects this duality. (Developmental Link: Timing differences in maturation of various parts of the brain is discussed in Chapter 14.)

The Irrational Adolescent

In describing adolescent cognition, intuitive and analytic thought are defined as follows:

Intuitive thought begins with a belief, assumption, or general rule (called a heuristic) rather than logic. Intuition is quick and powerful; it feels “right.”

Analytic thought is the formal, logical, hypothetical-

deductive thinking described by Piaget. It involves rational analysis of many factors whose interactions must be calculated, as in the scale- balancing problem.

When the two modes of thinking conflict, people of all ages sometimes use one and sometimes the other: We are all “predictably irrational” at times (Ariely, 2009). Adolescents tend to think quickly, because their reaction time is shorter than at any other time of life. That typically makes them “fast and furious” intuitive thinkers, unlike their teachers and parents, who prefer slower, more analytic thinking.

At every age, experiences and role models influence choices, not only in deciding what to do but also in choosing which intellectual process to use in making the decision. Conversations, observations, and debate all advance cognition and lead to conclusions that come from a deeper consideration of the facts (Kuhn, 2013).

Paul Klaczynski conducted dozens of studies comparing the thinking of children, young adolescents, and older adolescents (usually 9-

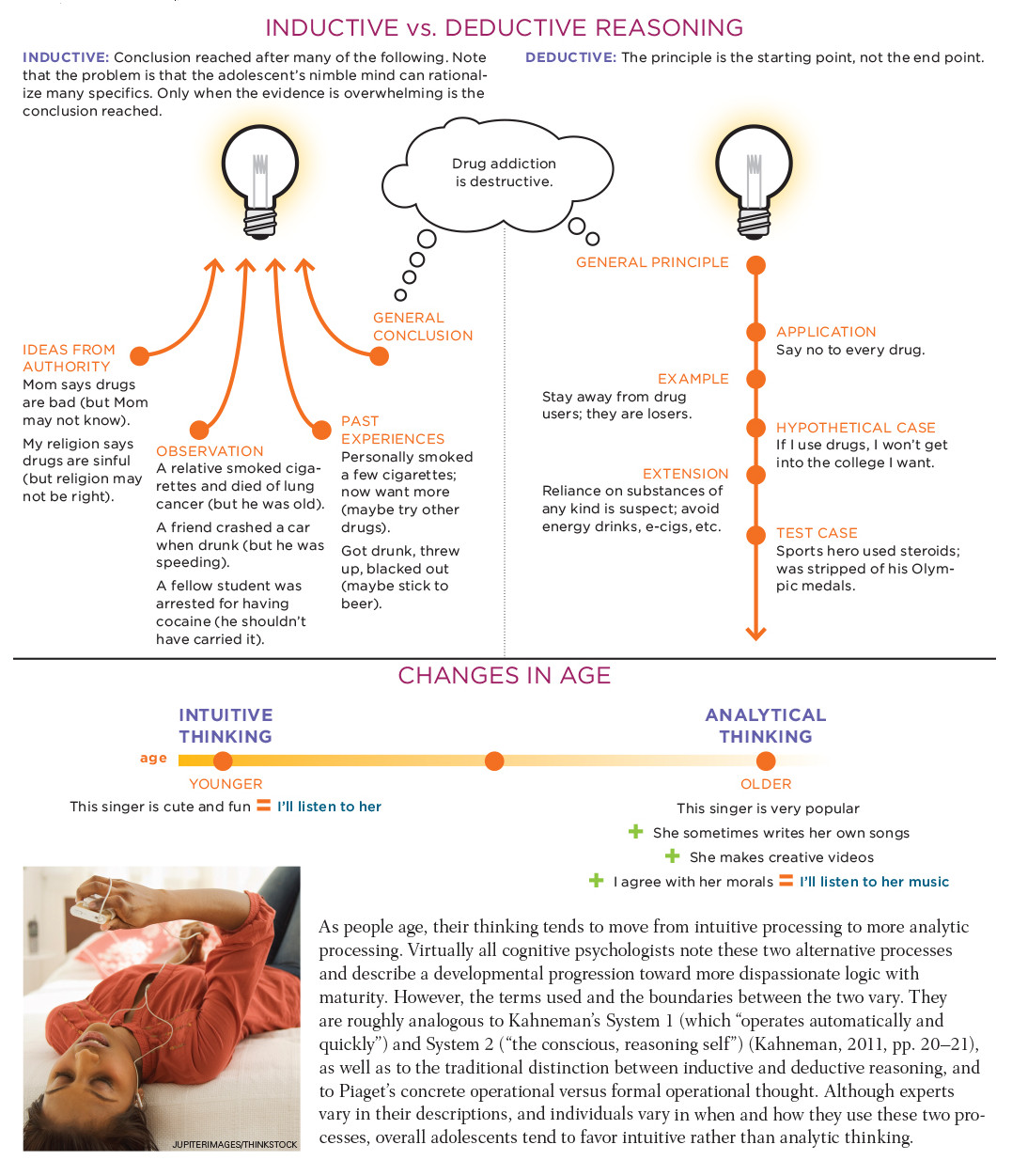

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Thinking in Adolescence

We are able to think both intuitively and analytically, but adolescents tend to rely more on intuitive thinking than do adults. As we age, we move toward more analytical processing.

To test yourself on intuitive and analytic thinking, answer the following three problems:

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

If it takes 5 minutes for 5 machines to make 5 widgets, how long would it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets?

In a lake, there is a patch of lily pads. Every day the patch doubles in size. If it takes 48 days for the patch to cover the entire lake, how long would it take for the patch to cover half the lake?

[From Gervais & Norenzayan, 2012]

|

Answers |

Intuitive (Incorrect) |

Analytic (Correct) |

|---|---|---|

|

1. |

10 cents |

5 cents |

|

2. |

100 minutes |

5 minutes |

|

3. |

24 days |

47 days |

Although many researchers find that logic gradually overcomes biased reasoning during adolescence, whether such analysis is used depends on specifics. For instance, older adolescents who idealized thinness were less likely to use logic to judge the weight of Jennifer, a hypothetical girl described as lazy and not well liked. Compared to younger adolescents, older adolescents more often jumped to the conclusion that Jennifer was obese (Klaczynski & Felmban, 2014).

In dozens of studies, being smarter as measured by an intelligence test does not advance logic as much as having more experience, in school and in life. Students can learn to use statistics and to respect expert opinion, and that helps them think more rationally—

Even though teenagers can use logic, sometimes they increasingly reason intuitively with age, especially when that intuitive reasoning activates stereotypes. Thus, “in certain domains, social variables are better predictors of age differences in heuristics and biases than cognitive abilities” (Klaczynski & Felmban, 2014, p. 103–

Preferring Emotions

Why not use formal operational thinking? Klaczynski’s participants had all learned the scientific method in school, and they knew that scientists use empirical evidence and deductive reasoning. But they did not always think like scientists. Why not?

Dozens of experiments and extensive theorizing have found some answers (Albert & Steinberg, 2011). Essentially, logic is more difficult than intuition, and it requires questioning ideas that are comforting and familiar. Once people of any age reach an emotional conclusion (sometimes called a “gut feeling”), they resist changing their minds. Prejudice does not quickly disappear because it is not seen as prejudice.

As people gain experience in making decisions and thinking things through, they may become better at knowing when analysis is needed (Milkman et al., 2009). For example, in contrast to younger students, when judging whether a rule is legitimate, older adolescents are more suspicious of authority and more likely to consider mitigating circumstances (Klaczynski, 2011). That may be wise—

Both suspicion of authority and awareness of context advance reasoning, but both also complicate simple issues or lead to impulsive but destructive actions. Indeed, suspicion of authority may propel adolescents to respond illogically. One of my students argued with a police officer who was about to charge her cousin, falsely, with playing hooky: When he moved to grab the cousin, she bit his hand—

Rational judgment is difficult when egocentrism dominates, and when the social demands outweigh the intellectual ones. Another psychologist discovered this personally when her teenage son phoned to be picked up from a party that had “gotten out of hand.” The boy heard

his frustrated father lament “drinking and trouble—

[Kuhn & Franklin, 2006, p. 966]

Better Thinking

Sometimes adults conclude that more mature thought processes are wiser, since they lead to caution (as in the father’s connection between “drinking and trouble”). Adults are particularly critical when egocentrism makes an impulsive teenager risk future addiction by experimenting with drugs or risk pregnancy and AIDS by not using a condom.

But adults may themselves be egocentric in making such judgments if they assume that adolescents share their values. Parents want healthy, long-

A 15-

Furthermore, weighing alternatives and thinking of possibilities can be paralyzing. The systematic, analytic thought that Piaget described is slow and costly, not fast and frugal, wasting precious time when a young person wants to act. Some risks are taken impulsively and foolishly.

Other risks are calculated in advance. The calculation may not be what the parents would do, but that does not mean the choice is not thought out (Maslowsky et al., 2011). Thus when parents discover that their child has done something contrary to the parents’ wishes, it is not necessarily because the heat of the moment overwhelmed cool rationality; it could be that the child rejected the parents’ directives after careful thought.

As the knowledge base increases and the brain matures, as impulses become less insistent and past experiences accumulate, both modes of thought become more forceful. With maturity, education, and conversation with those who disagree, adolescents are neither paralyzed by too much analysis nor plummeted into danger via intuition.

On average, logic increases from adolescence to adulthood (and then decreases somewhat in old age) (De Neys & Van Gelder, 2009; Kuhn, 2013). Always, however, the specific context, including superstitions and assumptions, makes a difference: We cannot assume that adolescent decisions are better than, or worse than, those of either children or adults (Furlan et al., 2013).

Thinking About Religion

As you remember from Chapter 1, scientists build on previous research or theories, replicating, extending, or refuting the work of others. Assumptions are questioned, empirical evidence is gathered to verify or criticize new theories and old cultural myths. This is a formal operational approach.

Some impressionistic descriptions of teenagers and religion (e.g., Flory & Miller, 2000) emphasize cults and sects. One observer reports that young congregants gather “dressed as they are, piercings and all, and express their commitment by means of hip-

These stereotypes evoke emotions—

Seeking evidence, not impressions, they surveyed 3,360 13-

They found that most adolescents (71 percent) felt close to God. They believed in heaven, hell, and angels and affirmed the same religion as their parents. Some were agnostic (2 percent), and 16 percent said they were not religious—

They also found that adolescents’ religious beliefs were often egocentric: Faith was a personal tool to be used in times of difficulty (e.g., while taking an exam). Many (82 percent) claimed their beliefs were important in daily life. One boy explained that religion kept him from doing “bad things, like murder or something,” and one girl said:

[Religion] influences me a lot with the people I choose not to be around. I would not hang with people that are, you know, devil worshipers because that’s just not my thing. I could not deal with that negativity.

[quoted in Smith, 2005, p. 139]

The researchers doubt that “socializing with Satanists is a real issue in this girl’s life” or that this boy “struggles with murderous tendencies” (Smith, 2005, p. 139). However, they also noted that few adolescents (less than 1 percent) used theology to guide them in the actual issues of daily life, such as seeking justice or loving one’s neighbor. For most, religious beliefs were intuitive, not analytic.

As good developmentalists, the researchers surveyed the same individuals three years later. They found a “shifting away from conventional religious beliefs” (Denton et al., 2008, p. 3). This trend was confirmed by another study of Canadian undergraduates about the same age as the U.S. participants at follow-

But, despite less certainty about God, angels, or an afterlife, the older adolescents in the U.S. study tended to feel they had become more, not less, religious over the three-

What does this imply for adults who hope to instill values in the next generation? In many ways, these data are encouraging: Most adolescents adhere to the faith of their parents. However, the authors wish that adults would encourage teenagers to discuss complex spiritual issues (e.g., stewardship of the environment, poverty, implications of scriptures). This would require parents and church leaders themselves to engage their analytic processes.

Dual Processing and the Brain

The brain maturation described in Chapter 14 seems directly related to the dual processes just explained. Because the limbic system is activated by puberty but the prefrontal cortex matures more gradually, it is easy to understand why adolescents are swayed by their intuition instead of by analysis.

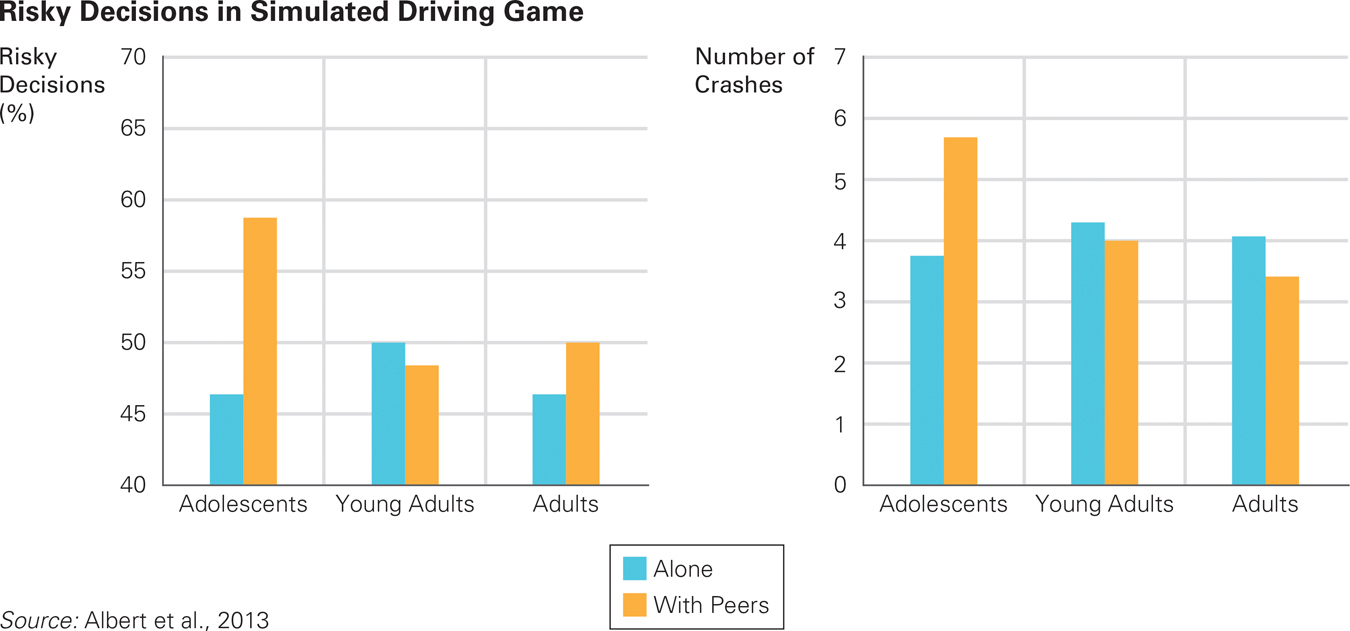

Since adolescent brains respond quickly and deeply to social rejection, teens readily follow impulses that promise social approval. In experiments in which adults and adolescents, alone or with peers, play video games in which taking risks might lead to crashes or gaining points, adolescents are much more likely than adults are to risk crashing, especially when they are with peers (Albert et al., 2013) (see Figure 15.3).

Losing Is Winning In this game, risk-

This explains why motor-

Per mile driven, drivers under 20 have fatal crashes about ten times more often than adults do. Don’t blame this only on inexperience; blame it on the need for acclaim. Some states now prohibit teen drivers from transporting other teenagers, a law that reduces deaths even as it bans one activity that adolescents enjoy.

Risk-

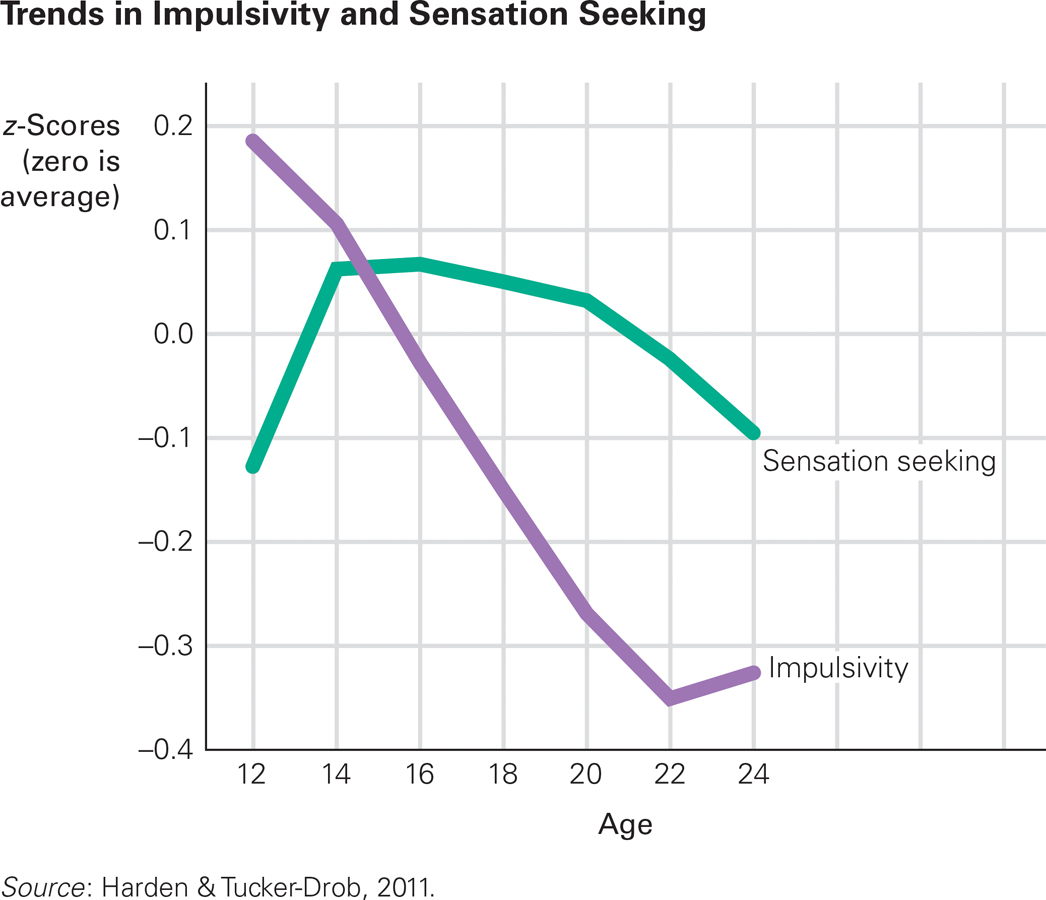

Because experiments that include brain scans are expensive, they rarely include many participants. However, less-

The results of that survey were “consistent with neurobiological research indicating that cortical regions involved in impulse control and planning continue to mature through early adulthood [and that] subcortical regions that respond to emotional novelty and reward are more responsive in middle adolescence than in either children or adults” (Harden & Tucker-

Specifically, this longitudinal survey traced sensation seeking (e.g., “I enjoy new and exciting experiences”) from early adolescence to the mid-

Look Before You Leap As you can see, adolescents become less impulsive as they mature, but they still enjoy the thrill of a new sensation.

The researchers also studied impulsivity, as indicated by agreement with statements such as “I often get in a jam because I do things without thinking.” A decline in impulsive action occurs as analytic thinking increases.

On average, sensation seeking accelerated rapidly at puberty, and both sensation seeking and impulsivity slowly decline with maturation. However, trajectories varied individually: Sensation seeking did not necessarily correlate with impulsivity. Thus, biology (the HPA system) is not necessarily linked to experience (the prefrontal cortex) (Harden & Tucker-

For example, hormone rushes in two adolescents might produce intense and identical drives for sex, but one teenager might have learned (directly or indirectly) to curb desire, while the other has had the opposite experiences. For the first, impulsivity would decline rapidly, as practice at saying no increases. This would not be true for the second adolescent, who would seek sexual pleasure as seen on a video, heard from a friend, or experienced before. Thus, both might experience equal sensation-

A practical application of this research comes from a program that teaches middle school students to avoid dating violence, both physical (e.g., hitting, kicking, pushing) and emotional (e.g., name-

A similar group of five other Texas schools had health classes as usual. The intervention reduced dating violence three years later, from 32 percent in the control group to 24 percent in the intervention group (Peskin et al., 2014). In other words, the classroom and parent discussions (“cold processing”) allowed the more reflective part of the students’ brains to grow—

SUMMING UP Current research recognizes that there are at least two modes of cognition, here called intuitive reasoning and analytical thought, although many other terms indicate two similar pairs. Intuitive thinking is experiential, quick, and impulsive, unlike formal operational thought. Both forms develop during adolescence. Sometimes intuitive processes crowd out analytic ones because emotions overwhelm logic, especially when adolescents are together. Each form of thinking is appropriate in some contexts. The capacity for logical, reflective thinking increases with neurological maturation, as the prefrontal cortex matures.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 15.7

When might intuition and analysis lead to contrasting conclusions?

Intuition begins with a belief, assumption, or general rule. It is quick and powerful—a gut reaction. Analysis is formal, logical, hypothetical thinking. It involves rational analysis of many factors. Intuition causes one to focus on the most interesting part of the problem, whereas analysis leads one to consider all aspects of the problem. Decisions based on intuition may lead one to take risks or jump to conclusions that analysis would help avoid. Question 15.8

What mode of thinking—

intuitive or analytic— do most people prefer, and why? People tend to use intuition in their everyday lives because it is faster and easier to rely on preexisting beliefs, assumptions, and rules than it is to reason deliberately.Question 15.9

How does personal experience increase the probability of base rate neglect?

Base rate neglect is a common error in adolescent thinking. If presented with related base rate information (generic, general facts) and specific information (such as one example), the mind tends to ignore the former and focus on the latter. It is why people are more afraid of flying than driving even though they are much more apt to perish driving than flying. When a plane crashes, it makes headline news, causing people to believe it is a more common occurrence than it actually is. If, for example, a teen has never had a bicycle wreck, he or she may refuse to wear a helmet regardless of evidence that wearing a helmet saves lives every day. However, if a classmate suffers injury from a bike accident, the teen may change his or her attitude toward wearing a helmet. Once bike injuries become personal and thus in the teen's orbit, they become more “real.”Question 15.10

How does egocentrism account for the clashing priorities of parents and adolescents?

Adolescents see themselves as far more important and socially significant than they actually are. A parent's desire for appropriate clothing, music, grades, friends, and decisions about the future may clash with the teenager's exaggerated sense of importance and influence. Parents assume teens share their values and think as they think.Question 15.11

When is intuitive thinking better than analytic thinking?

Analytic thinking could be best used when making major decisions, like whom to marry or which investment to make, since one weighs the alternatives and thinks of other possibilities when using this mode of thought. Intuitive thinking is “fast and frugal.” It is less paralyzing to make an emotional decision, which makes intuition the best and quickest route in social circumstances.Question 15.12

How can it be that adolescents attend services less often but claim to be more spiritual as they age?

One possible reason is that as adolescents develop and mature, they take more ownership over their own beliefs and practices so that their religiosity feels stronger and more authentic. In other words, maturation, independence, and years of questioning may advance thinking about religion as well as about everything else.Question 15.13

What is the relationship between adolescent brain development and the two modes of thought?

The two modes of thought are intuitive thinking and analytical thinking. Intuitive thinking is associated with the limbic system while analytical thinking is associated with the prefrontal cortex. The limbic system matures more quickly than the prefrontal cortex and as a result adolescents tend to rely more on intuition than analysis when making decisions. This tendency towards quick. intuitive, thinking can be characterized as 'fast and furious'.