Digital Natives

Adults over age 40 grew up without the Internet, instant messaging, Twitter, Snapchat, blogs, cell phones, smartphones, MP3 players, tablets, or digital cameras. At first, the Internet was only for the military, then primarily for businesses and the educated elite. Until 2006, only students at elite colleges could join Facebook.

In contrast, today’s teenagers have been called digital natives, although if that term implies that they know everything about digital communication, it is a misnomer (boyd, 2014). There is no doubt, however, that today’s adolescents have been networking, texting, and clicking for definitions, directions, and data all their lives. Their cell phones are within reach, day and night.

A huge gap between those with and without computers was bemoaned a decade ago; it divided boys from girls and rich from poor (Dijk, 2005; Norris, 2001). Now that digital divide is shrinking.

In developed nations, virtually every school and library is connected to the Internet, as are many in developing nations. This opens up new ideas and allows access to like-

As costs tumble, the device that has been particularly important at creating digital natives among low-

Although discrepancies in number and quality of devices still follow SES lines, the most notable digital divide is now age: Each older generation is less likely to use the Internet than the next younger one. That may explain why people bemoaning the effects of technology on adolescent minds tend to be over age 50.

Question 15.14

OBSERVATION QUIZ Beyond the smartphones, what two signs of adolescent conformity are apparent?

Hair and jeans. A few decades ago, if girls wore jeans, they might be black or green, and hair was curly. But now, at least for these three at a Texas high school, jeans must be blue and tight, and hair straight and long—

Technology and Cognition

In general, educators accept, even welcome, students’ facility with technology. In many high schools, teachers use laptops, smartphones, and so on as tools for learning. In some districts, students are required to take at least one class completely online. There are “virtual” schools, in which students earn all their credits online, never entering a school building, and in Maine all high school students have laptops (Silvernail et al., 2011).

Some programs and games have been designed for high school classes. For example, ten teachers were taught how to use a game (Mission Biotech) to teach genetics and molecular biology. Their students—

Remember that research before the technology explosion found that instruction, practice, conversation, and experience advance adolescent thought. Social networking via technology may speed up this process, as teens communicate daily with dozens—

Most secondary students check facts, read explanations, view videos, and thus grasp concepts they would not have understood without technology. For some adolescents, the Internet is their only source of information about health and sex. Almost every high school student in the United States uses the Internet for research, finding it quicker and its range of information more extensive than books on library shelves.

A major concern is that adolescents do not evaluate what they see on the screen as carefully as they should, nor understand the implications of sending a message on impulse. Messages endure, and can be seen by hundreds, sometimes thousands, of unintended recipients, sometimes with unanticipated harm to others or oneself (boyd, 2014).

Video: The Impact of Media on Adolescent DevelopmentMONKEY BUSINESS IMAGES/SHUTTERSTOCK

Teachers use the Internet not only for research and assignments but also to judge whether or not a student’s paper is plagiarized. Educators claim that the most difficult aspect of technology is teaching students how to evaluate sources, some reputable, some nonsensical. To this end, teachers explain the significance of .com, .org, .edu, and .gov (O’Hanlon, 2013).

In Maine, giving each student a laptop to use in school seems a cost-

A New Addiction?

Parents worry about sexual abuse via the Internet. Research is reassuring: Although sexual predators lurk online, most teens never encounter them. Sexual abuse is a serious problem, but if sexual abuse is defined as a perverted older stranger taking advantage of an innocent teenager, it is “extremely rare” (Mitchell et al., 2013, p. 1226).

Between 2000 and 2010, percent of teenagers who say that someone online tried to get them to talk about sex declined from 10 percent to 1 percent. Those 1 percent were almost always solicited by another young person whom the teenager knew in person—

Teenagers are actually more suspicious of strangers than they were before the Internet, partly because parents and the police have alerted them to the danger. A Web-

Our data suggest that it would be beneficial for policy-

[Mitchell et al., 2013, p. 1233]

As the next chapter explains, teenagers have much to learn about sex and self-

These myth-

Even when no social harm occurs, technology may present some dangers, however. It encourages rapid shifts of attention, multitasking without reflection, and visual learning instead of invisible analysis (Greenfield, 2009). Video games with violent content promote aggression (Gentile, 2011).

For some adolescents, chat rooms, video games, and Internet gambling are considered addictive, taking time from active play, schoolwork, and friendship. For teenagers with a troubled family life, Internet addiction is considered a problem worldwide, particularly in China (Tang et al., 2014).

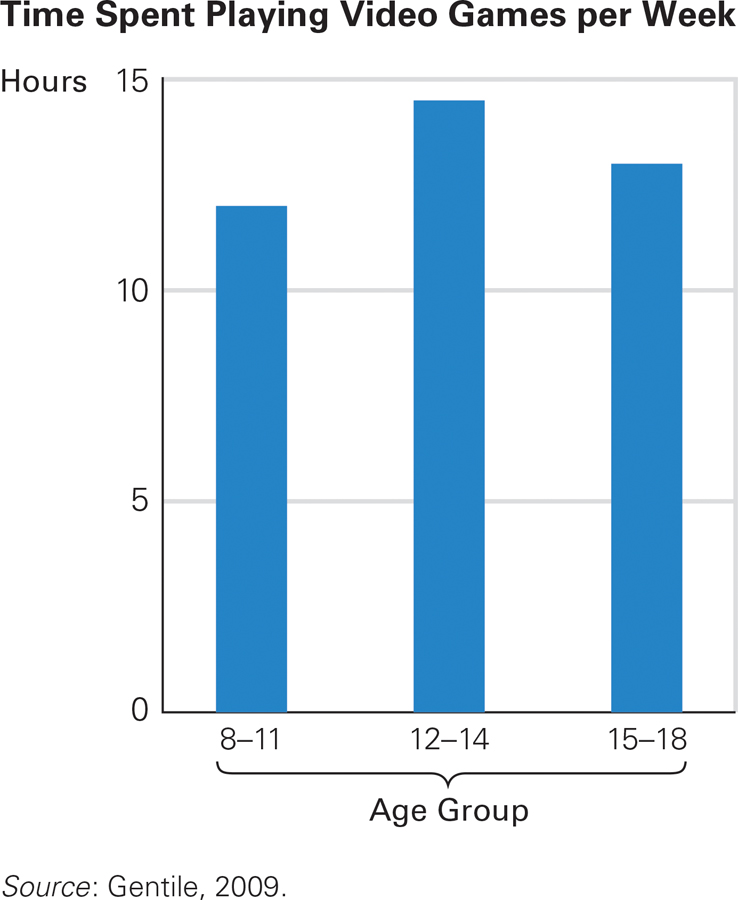

This is not mere speculation. A study of almost two thousand older children and adolescents in the United States found that the average person played video games two hours a day. Some played much more, and only 3 percent of the boys and 21 percent of the girls never played (Gentile, 2011) (see Figure 15.5). Another survey found that almost one-

More Than Eating The average adolescent boy spends more time playing video games than reading, eating, doing homework, talking with friends, playing sports, or almost anything else except sleeping or sitting in class. Indeed, some skip school or postpone sleep to finish a game.

At what point and for whom does this become truly addictive instead of normal teen behavior? Many adolescents in the first survey admit that video-

Using criteria for addiction developed by psychiatrists for other addictions (gambling, drugs, and so on), one study found that 12 percent of the boys and 3 percent of the girls were addicted to playing video games. However, correlation is not causation: Perhaps low school achievement led to video game playing rather than vice versa. Some scholars worry that adults tend to pathologize normal teen behavior, once again particularly in China, where rehabilitation centers are strict—

Studies in many nations judge a sizable minority of high school students (e.g., 15 percent in Turkey, 12 percent in India) as “addicted” to computer use (S¸as¸maz et al., 2014; Yadav et al., 2013). Reviewing research from many nations, one team of researchers report addiction rates from 0 to 26 percent. The variation was caused more by differing definitions and procedures among researchers than by differences among students in any particular place (Y. Lee et al., 2014).

The fear that the Internet may undercut school achievement seems justified, however. A study began with younger boys whose parents intended to buy them a video game system. (Such a study could not have been done with adolescents, because almost all adolescents who want to play games online already have the equipment to do so.) Randomly, half of them were given the system, and the other half had to wait four months. Those who immediately received the video game system had lower reading and writing achievement after four months than did their peers who waited (Weis & Cerankosky, 2010).

Most screen time occurs in the child’s own bedroom. About half of all parents place no restrictions on technology use, as long as their adolescent is safe at home. Other parents place many restrictions on their children—

Some suggest that technology should be banned from schools and bedrooms, but, as one critic writes, “we don’t ban pencils and paper because students pass notes” (Shuler, 2009, p. 35). Some teachers confiscate computers and cell phones used in class, others ignore them, and still others include them in the curriculum.

Whether extensive use of the Internet qualifies as an addiction is controversial. The psychiatrists who wrote the new DSM-

Cyber Danger

Now let us focus on the danger from Internet use that seems most valid. When a person is bullied via electronic devices, usually via social media, text messages, or cell phone videos, that is cyberbullying (Tokunaga, 2010). The adolescents most involved in cyberbullying are usually already bullies or victims or both, with bully-

Worst in Adolescence

Texted and posted rumors and insults can “go viral,” reaching thousands, transmitted day and night. The imaginary audience magnifies the shame. Not only words but also photos and videos can be easily sent: Some adolescents take video of others drunk, naked, or crying and send that to dozens of others, who may send it to yet others, who may post it on YouTube or Vine. Since young adolescents are impulsive and low on judgment, cyberbullying is particularly prevalent and sometimes thoughtlessly cruel between ages 11 and 14.

While the causes of all forms of bullying are similar, each form has its own sting: Cyberbullying may be worst when the victim believes in the imaginary audience, when the identity is forming, when sexual impulses are new, and when impulsive thoughts precede analytic ones—

Adolescent victims are likely to suffer from depression, because cyberbullying adds to the typical rise in depression that occurs at puberty. In extreme cases, cyberbullying may be the final straw that triggers suicide (Bonanno & Hymel, 2013).

The school climate affects all forms of bullying. When students consider school a good place to be—

Some people believe that cyberbullying is unstoppable. Nonetheless, teens themselves use successful strategies, such as deleting messages from bullies (Parris et al., 2012). As with other forms of bullying, cyberbullies and victims are influenced by the context, which can make it more or less harmful (Kowalski et al., 2014).

One complication is that most adolescents trust technology while many adults ignore it. Parents often are unaware of cyberbullying, and few laws and policies successfully prevent it. Some school administrators insist they cannot stop cyberbullying because it does not emanate from school computers. However, cyberbullying usually occurs among classmates and can poison the school climate, and thus educators must be concerned. Adolescents are vulnerable; they need more protection than most adults realize (boyd, 2014).

Sexting

The vulnerability of adolescence was tragically evident in the suicide of a California 15-

One aspect of this tragedy will come as no surprise to adolescents: “sexting,” as sending sexual photographs is called. As many as 30 percent of adolescents report having received sexting photos, with marked variation by school, gender, and ethnicity and often in attitude: Many teens send their own sexy “selfies” and are happy to receive sext messages (Temple et al., 2014). As with Internet addiction, researchers have yet to agree on how to measure sexting or how harmful it is.

There are evidently two dangers: (1) pictures may be forwarded without the naked person’s knowledge, and (2) senders who deliberately send erotic self-

Other Hazards

Internet connections allow troubled adolescents to connect with others who share their prejudices and self-

The danger of all forms of technology lies not in the equipment but in the cognition of the user. As is true of many aspects of adolescence (puberty, brain development, egocentric thought, use of contraception, and so on), context, adults, peers, and the adolescent’s own personality and temperament “shape, mediate, and/or modify effects” of technology (Oakes, 2009, p. 1142).

One careful observer claims that instead of being native users of technology, many teenager are naïve users. They believe they have privacy settings that they do not have, trust sites that are markedly biased, misunderstand how to search for and verify information (boyd, 2014).

Educators can help with all this—

SUMMING UP In fostering adolescent cognition, technology has many positive aspects: A computer is a tool for learning and providing information far more specific and wide-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 15.15

What benefits come from adolescents’ use of technology?

Research conducted before the technology explosion found that with education, conversation, and experience, adolescents move past egocentric thought. Social networking may speed up this process, as teens communicate daily with dozens of friends via e–mail, texting, and cell phones. Question 15.16

Why is adult fear of online adult predators exaggerated?

Although sexual predators lurk online, most teens never encounter them. Sexual abuse is a serious problem, but if sexual abuse is defined as a perverted older stranger taking advantage of an innocent teenager, it is “extremely rare.”Question 15.17

How do video games affect student learning?

Internet use and video games improve visual–spatial skills and vocabulary. Technology does present some dangers, as well. Video games with violent content promote aggression, and chat rooms, video games, and Internet gambling are addictive for some adolescents, taking time from needed play, schoolwork, and friendship. Question 15.18

Who is most and least involved in cyberbullying?

The adolescents most involved are usually already bullies or victims or both, with bully–victims the most likely to engage in, and suffer from, cyberbullying. When students consider their school a good place to be, teens with high self– esteem are not only less likely to engage in cyberbullying but also to disapprove of it among peers. Question 15.19

Why might sexting be a problem?

There are two possible dangers: (1) pictures may be forwarded without the naked person's knowledge, and (2) senders who deliberately send erotic self–images risk serious depression if the reaction is not what they wished. Question 15.20

In what way is the term “digital native” valid and how is it misleading?

Adults over age 40 grew up without the Internet, instant messaging, Twitter, Snapchat, blogs, cell phones, smartphones, MP3 players, tablets, or digital cameras. At first, the Internet was only for the military, then primarily for businesses and the educated elite. Until 2006, only students at elite colleges could join Facebook. However, today's teenagers have been called digital natives, although if that term implies that they know everything about digital communication, it is a misnomer. There is no doubt that today's adolescents have been networking, texting, and clicking for definitions, directions, and data all their lives. Their cell phones are within reach, day and night.