Teaching and Learning

What does our knowledge of adolescent thought imply about school? Educators, developmentalists, political leaders, and parents wonder exactly which curricula and school structures are best for 11-

To complicate matters, adolescents are far from a homogeneous group. As a result,

some youth thrive at school—

[Eccles & Roeser, 2011, p. 225]

Given all these variations, no single school structure or style of pedagogy seems best for everyone. Various scientists, nations, schools, and teachers try many strategies, some based on opposite but logical hypotheses. To begin to analyze this complexity, we present definitions, facts, issues, and possibilities.

Definitions and Facts

Each year of schooling advances human potential, a fact recognized by leaders and scholars in every nation and discipline. As you have read, adolescents are capable of deep and wide-

Secondary education—traditionally grades 7 through 12—

Even cigarette-

These cigarette data are typical: Data on almost every condition, from every nation and ethnic group, confirm that high school and college graduation correlates with better health, wealth, and family life. Some reasons are indirectly related to education (e.g., income and place of residence), but even when poverty and toxic neighborhoods are equalized, education confers benefits.

Partly because political leaders recognize that educated adults advance national wealth and health, every nation is increasing the number of students in secondary schools. Education is compulsory until at least age 12 almost everywhere, and new high schools and colleges open daily in developing nations.

The two most populous countries, China and India, are characterized by massive growth in education. In India, for example, less than 1 percent of the population graduated from high school in 1950; the 2002 rate was 37 percent; the 2010 rate was 50 percent; now it is even higher (Bagla & Stone, 2013).

In many nations, two levels of secondary education are provided. Traditionally, secondary education was divided into junior high (usually grades 7 and 8) and senior high (usually grades 9 through 12). As the average age of puberty declined, middle schools were created for grades 6 to 8, and sometimes for grades 5 to 8.

Middle School

Adjusting to middle school is bound to be stressful, as teachers, classmates, and expectations all change. Regarding learning, “researchers and theorists commonly view early adolescence as an especially sensitive developmental period” (McGill et al., 2012, p. 1003). Yet many developmentalists find middle schools to be “developmentally regressive” (Eccles & Roeser, 2010, p. 13), which means learning goes backward.

Increasing Behavioral Problems

Especially for Teachers You are stumped by a question your student asks. What do you do?

Praise a student by saying, “What a great question!” Egos are fragile, so it’s best to always validate the question. Seek student engagement, perhaps asking whether any classmates know the answer or telling the student to discover the answer online or saying you will find out. Whatever you do, don’t fake it; if students lose faith in your credibility, you may lose them completely.

For many middle school students, academic achievement slows down and behavioral problems increase. Puberty itself is part of the problem. At least for other animals studied, especially when they are under stress, learning is reduced at puberty (McCormick et al., 2010).

For people, the biological and psychological stresses of puberty are not the only reason learning suffers in early adolescence. Cognition matters, too: How much new middle school students like their school affects how much they learn (Riglin et al., 2013).

A longitudinal study found a decline in school interests and grades from age 7 to 16, with a notable dip in the transition to middle school (Dotterer et al., 2009). African American and Latino middle school students particularly seem less engaged in school (McGill et al., 2012; Hayes et al., 2014). Students become aware of expectations for them in the larger community. This makes the decline in academics particularly steep for young adolescents of ethnic minorities.

Unfortunately, many students of every group have reasons to dislike middle school compared to elementary school. Bullying is common in middle school, particularly in the first year (Baly et al., 2014). Middle schools undercut student–

Unlike primary school, when each classroom has one teacher all year, middle school teachers may have hundreds of students. They become impersonal and distant, opposite to the direct, personal engagement that young adolescents need.

a case to study

James, the High-

A longitudinal study in Massachusetts followed children from preschool through high school. James was one of the most promising. In his early school years, he was an excellent reader whose mother took great pride in him, her only child. Once James entered middle school, however, something changed:

Although still performing well academically, James began acting out. At first his actions could be described as merely mischievous, but later he engaged in much more serious acts, such as drinking and fighting, which resulted in his being suspended from school.

[Snow et al., 2007, p. 59]

Family problems increased. James and his father blamed each other for their poor relationship, and his mother bragged “about how independent James was for being able to be left alone to fend for himself,” while James “described himself as isolated and closed off” (Snow et al., 2007, p. 59).

James said, “The kids were definitely afraid of me but that didn’t stop them” from associating with him (Snow et al., 2007, p. 59). James’s experience is not unusual. Generally, aggressive and drug-

This is not true only for African American boys like James. There is “an abundance of evidence of middle school declines on a number of academic outcomes” (McGill et al., 2012). There is also evidence that middle school achievement predicts which students will graduate from high school and then who will go to college (Center for Education Policy, 2012).

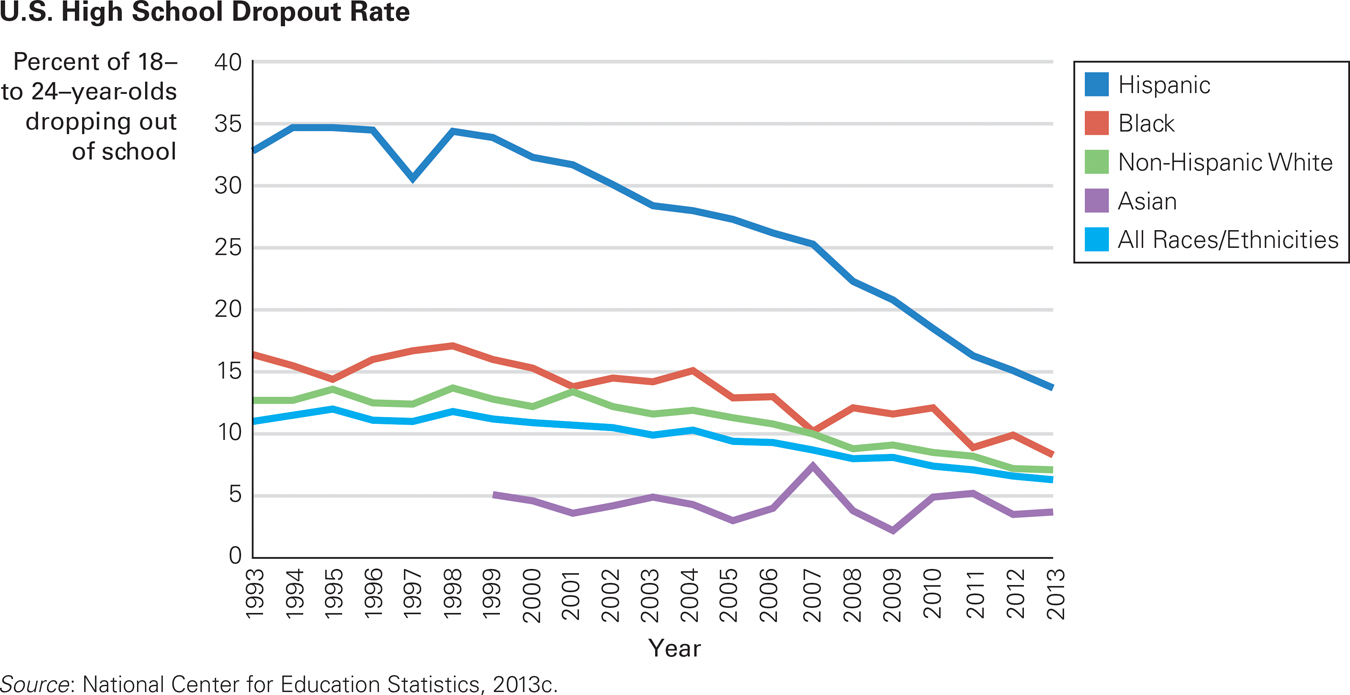

Although girls’ achievement also declines in middle school, they are less likely to quit than boys. For the past four decades (since 1977) in the United States and in many other nations, fewer boys have graduated from high school than girls. As a result, according to U.S. data for 2011, males ages 16 to 24 were 18 percent more likely than females to leave high school before graduation (National Center for Education Statistics, 2013c).

At the end of primary school, James planned to go to college; in middle school, he said he had “a complete lack of motivation”; in tenth grade, he dropped out.

As was true for James, the early signs of a future high school dropout are found in middle school. Those students most at risk of leaving before graduation are low-

Finding Acclaim

To pinpoint the developmental mismatch between students’ needs and the middle school context, note that just when egocentrism leads young people to feelings of shame or fantasies of stardom (the imaginary audience), schools typically require them to change rooms, teachers, and classmates every 40 minutes or so. That makes both public acclaim and supportive new friendships difficult to achieve.

Recognition for academic excellence is especially elusive because middle school teachers mark more harshly than their primary school counterparts. Effort without accomplishment is not recognized, and achievement that was earlier “outstanding” is now only average. Acclaim for after-

Many middle school students seek acceptance from their peers. Bullying increases, physical appearance becomes more important, status symbols are displayed (from gang colors to trendy sunglasses), expensive clothes are coveted, and sexual conquests are flaunted. Of course, much depends on the cultural context, but almost every middle school student seeks peer approval in ways that adults disapprove (Véronneau & Dishion, 2010), a topic further discussed in the next chapter.

Coping with Middle School

One way to cope with stress is directly cognitive, that is, to blame classmates, teachers, parents, or governments for any problems. This may explain the surprising results of a Los Angeles study: Students in schools that were more ethnically mixed felt safer and less lonely. They did not necessarily have friends from other groups, but students who felt rejected could “attribute their plight to the prejudice of other people” rather than blame themselves (Juvonen et al., 2006, p. 398). Furthermore, since each group was a minority, the students tended to support and defend other members of their group, giving each individual some ethnic allies.

Another way middle school students avoid failure is to quit trying. Then they can blame a low grade on their choice (“I didn’t study”) rather than on their ability. Pivotal is how they think of their potential.

If they hold to the entity theory of intelligence (i.e., that ability is innate, a fixed quantity present at birth), then they conclude that nothing they do can improve their academic skill. If they think they are innately incompetent at math, or reading, or whatever, they mask that self-

By contrast, if adolescents adopt the incremental theory of intelligence (i.e., that intelligence can increase if they work to master whatever they seek to understand), they will pay attention, participate in class, study, complete their homework, and learn. That is also called mastery motivation, an example of intrinsic motivation. (Developmental Link: Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation are discussed in Chapter 10; stereotype threat in the epilogue.)

Especially for Middle School Teachers You think your lectures are interesting and you know you care about your students, yet many of them cut class, come late, or seem to sleep through it. What do you do?

Students need both challenge and involvement; avoid lessons that are too easy or too passive. Create small groups; assign oral reports, debates, and role-

This is not hypothetical. In the first year of middle school, students with entity beliefs do not achieve much, whereas those with mastery motivation improve academically, as found in many nations including Norway (Diseth et al., 2014), China (Zhao & Wang, 2014), and the United States (Burnette et al., 2013).

The implicit belief that skills can be mastered is crucial for learning social skills as well as academic ones (Dweck, 2013). Students are highly motivated to improve their peer relationships. Adults need to convince them that improvement is possible, and then guide them. That advances academic as well as social skills.

The contrast between the entity and incremental theories is apparent not only for individual adolescents but also for teachers, parents, schools, and cultures. If the hidden curriculum endorses competition among students and tells some students they are not “college material,” then everyone believes the entity theory, and students are unlikely to help each other (Eccles & Roeser, 2011). If a teacher believes that some children cannot learn much, then they won’t.

International comparisons reveal that educational systems that track students into higher or lower classes, that expel low-

High School

Many of the patterns and problems of middle school continue in high school, although with puberty over, adolescents are better able to cope. As we have seen, adolescents become increasingly able to think abstractly, analytically, hypothetically, and logically (all formal operational thought) as well as subjectively, emotionally, intuitively, and experientially. High school curricula and teaching methods often require the former mode.

The College-Bound

From a developmental perspective, the fact that high schools emphasize formal thinking makes sense, since many older adolescents are capable of abstract logic.

In several nations, attempts are underway to raise standards so that all high school graduates will be ready for college. For that reason, U.S. schools are increasing the number of students who take classes that are assessed by externally scored exams, either the IB (International Baccalaureate) or the AP (Advanced Placement).

Such classes satisfy some college requirements if the student scores well. More and more students are taking AP and IB classes: 33 percent of high school graduates did so in 2013, compared to 19 percent in 2003 (Adams, 2014).

Some students are discouraged from taking the AP exams, and those who avoid taking AP classes are often African or Latino American. Some students who might pass do not enroll—

Another problem is that taking an AP class does not necessarily lead to college readiness (Sadler et al., 2010). One study showed that overall, almost a third of those who took the exam failed. Failure rates were higher among African Americans, lower among Latino and Asian Americans (Adams, 2014). The IB is less common, but again, few receive the highest scores.

Especially for High School Teachers You are much more interested in the nuances and controversies than in the basic facts of your subject, but you know that your students will take high-

It would be nice to follow your instincts, but the appropriate response depends partly on pressures within the school and on the expectations of the parents and administration. A comforting fact is that adolescents can think about and learn almost anything if they feel a personal connection to it. Look for ways to teach the facts your students need for the tests as the foundation for the exciting and innovative topics you want to teach. Everyone will learn more, and the tests will be less intimidating to your students.

Students who score well on AP or IB tests tend to do well in college. Since students who are capable and motivated, and who have college-

Of course, AP and IB exams are not the only measure of high school rigor. Another indicator is an increase in the requirements to receive an academic diploma. (In many U.S. schools, no one is allowed to earn a vocational or general diploma unless parents request it.) Graduation requirements usually include two years of math beyond algebra, two years of laboratory science, three years of history, and four years of English. Learning a language other than English is often required as well. Standards within those classes have often been raised by the Common Core, accepted by some, not all, high schools.

In addition to mandated courses, 24 U.S. states now also require students to pass a high-

opposing perspectives

Testing

Secondary students in the United States take many more tests than they did even a decade ago. This includes many high-

Testing begins long before high school: Many students take high-

All tests may be high stakes for teachers, who can earn extra pay or lose their job based on how their students score, and for schools, which may gain resources or be closed because of test scores. Even entire school systems are rated on test scores, and this is said to be one reason widespread cheating occurred in Atlanta beginning in 2009 (Severson & Blinder, 2014).

Opposing perspectives on testing are voiced within many schools, parent groups, and state legislatures. In 2013, Alabama dropped its high-

Overall, high school graduation rates in the United States have increased every year for the past decade, reaching 80 percent in 2012 (see Figure 15.6). Some say that tests and standards are part of the reason, but the data suggest that the high-

Mostly Good News This depicts wonderful improvements in high school graduation rates, especially among Hispanic youth, who drop out only half as often as they did twenty years ago. However, since high school graduation is increasingly necessary for lifetime success, even the rates shown here may not have kept pace with the changing needs of the economy. Future health, income, and happiness for anyone who drops out may be in jeopardy.

Students who fail exams are often those with designated learning disabilities, one-

A panel of experts found that too much testing reduces learning rather than advances it (Hout & Elliot, 2011). But how much is “too much”?

One expert recommends “using tests to motivate students and teachers” (Walberg, 2011, p. 7). He believes that well-

Ironically, just when U.S. schools are raising requirements, many East Asian nations, including China, Singapore, and Japan (all with high scores on international tests), are moving in the opposite direction. Particularly in Singapore, national high-

By contrast, other nations, including Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom, have instituted high-

A team of Australian educators reviewed all the evidence and concluded:

What emerges consistently across this range of studies are serious concerns regarding the impact of high stakes testing on student health and well-

[Polesel et al., 2012, p. 5]

International data support both sides of this controversy. One nation whose children generally score well is South Korea, where high-

On the opposite side of the globe, students in Finland also score very well on international tests, and yet they have no national tests until the end of high school. Nor do they spend much time on homework or after-

The most recent international data suggest that U.S. high school students are not doing well, despite more high-

A third set of international tests, the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment, to be explained soon), places U.S. students even lower. The 2012 results from the 65 nations that took the tests puts the U.S. 36th in math, 28th in science, and 24th in reading—

Again in 2012 as in former years, China, Japan, Singapore, and Korea were at the top. Tellingly, the results for the United States lagged behind the nation most similar in ethnicity and location—

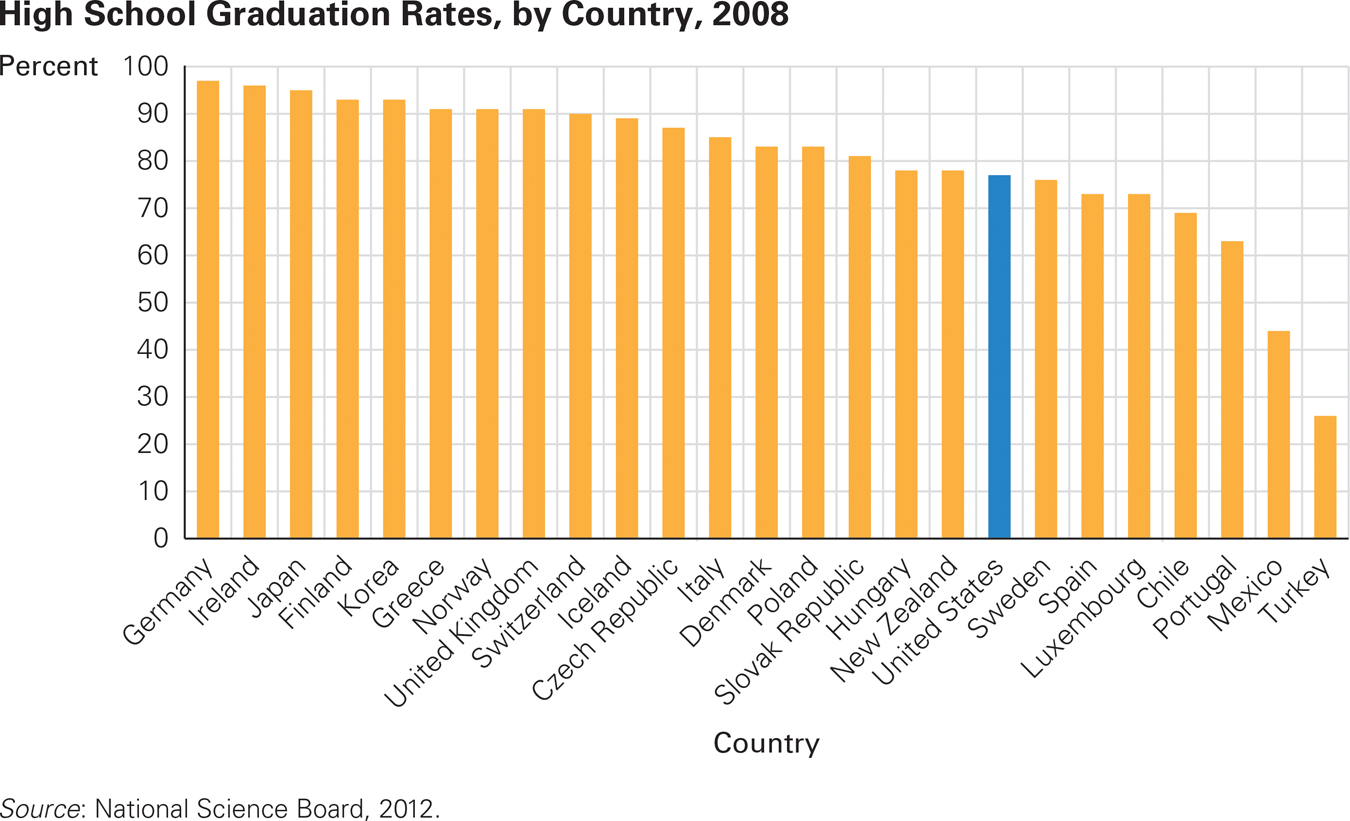

In many nations, scores on those three international tests as well as other metrics compel reexamination of school policies and practices. That certainly is true in the United States, which trails other developed nations in high school graduation rate (see Figure 15.7). Whether tests will change that is controversial: Many legislators believe so; many educators disagree.

Children Left Behind High school graduation rates in almost every nation and ethnic group are improving. However, the United States still lags behind other nations, and ethnic differences persist, with the rate among Native Americans lowest and among Asian Americans highest. High school diplomas are only one sign of educational accomplishment: Nations at the top of this chart tend also to rank highest in preschool attendance, in middle school achievement, and in college graduation. Raising the graduation rate involves the entire educational system, not simply more rigorous or more lenient graduation standards.

College for Everyone?

In the United States, a sizable minority (about 30 percent) of high school graduates do not enter college. Moreover, of those who enter public community colleges, most (about three-

Rates are even lower in many of the largest cities. For example, only 18 percent of the approximately 60,000 students entering ninth grade public schools in the district of Philadelphia managed to graduate on time from high school and then complete at least two years of college (Center for Education Policy, 2013).

The 82 percent who fell off track are often a disappointment to their parents: In Philadelphia and nationwide, almost all parents hope their children will graduate from college. The students may be a disappointment to themselves as well. Many quit high school before their senior year, but among the Philadelphia seniors, 84 percent plan to go to college but only 47 percent enroll the following September. Some will begin college later, but their chance of college completion is low.

These sobering statistics underlie another debate among educators. Should students be encouraged to “dream big” early in high school, aspiring for tertiary learning? This suggestion originates from studies that find a correlation between dreaming big in early adolescence and going to college years later (Domina et al., 2011a, 2011b). Others suggest that college is a “fairy tale dream” that may lead to low self-

Business leaders have another concern: that high school graduates are not ready for the demands of work because their education has been too abstract. They have not learned enough through discussion, emotional maturation, and real-

Internationally, vocational education that explicitly prepares students for jobs via a combination of academic classes and practical experience seems to succeed better than a general curriculum (Eichhorst et al., 2012). On the other hand, in the United States, many students whose test scores suggest they could succeed at a four-

For example, students who entered high school with high scores in two major cities in neighboring states (Albuquerque, New Mexico and Fort Worth, Texas) had markedly different college enrollment rates (Albuquerque was 83 percent, compared to 58 percent in Fort Worth) (Center for Education Policy, 2012).

Overall, the data present a dilemma for educators. Suggesting that a student should not go to college may be racist, classist, sexist, or worse. On the other hand, many students who begin college do not graduate, so they lose time and gain debt when they could have advanced in a vocation. Everyone agrees that adolescents need to be educated for life as well as employment, but it is difficult to decide what that means.

Measuring Practical Cognition

Employers usually provide on-

As one executive of Boeing (which hired 33,000 new employees in two years) wrote:

We believe that professional success today and in the future is more likely for those who have practical experience, work well with others, build strong relationships, and are able to think and do, not just look things up on the Internet.

[Stephens & Richey, 2013]

Those skills are hard to measure, especially on national high-

The third set of international tests mentioned above, the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment), was designed to measure students’ ability to apply what they have learned. The PISA is taken by 15-

The tests are designed to generate measures of the extent to which students can make effective use of what they have learned in school to deal with various problems and challenges they are likely to experience in everyday life.

[PISA, 2009, p. 12]

For example, among the 2012 math questions is this one:

Chris has just received her car driving license and wants to buy her first car. The table below shows the details of four cars she finds at a local car dealer.

|

Model |

Alpha |

Bolte |

Castel |

Dezal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

2003 |

2000 |

2001 |

1999 |

|

Advertised price (zeds) |

4800 |

4450 |

4250 |

3990 |

|

Distance travelled (kilometers) |

105 000 |

115 000 |

128 000 |

109 000 |

|

Engine capacity (liters) |

1.79 |

1.796 |

1.82 |

1.783 |

What car’s engine capacity is the smallest?

A. Alpha B. Bolte C. Castel D. Dezal

For that and the other questions on the PISA, the calculations are quite simple—

As noted in Opposing Perspectives, overall the U.S. students perform lower on the PISA compared to many other nations. International analysis finds that the following items correlate with high achievement (OECD, 2010, p. 6):

Leaders, parents, and citizens value education overall, with individualized approaches to learning so that all students learn what they need.

Standards are high and clear, so every student knows what he or she must do, with a “focus on the acquisition of complex, higher-

order thinking skills.” Teachers and administrators are valued, and they are given “considerable discretion … in determining content” and sufficient salary as well as time for collaboration.

Learning is prioritized “across the entire system,” with high-

quality teachers working in the most challenging environments.

The PISA and international comparisons of high school dropout rates suggest that U.S. secondary education can be improved, especially for those who do not go to college. Surprisingly, students who are capable of passing their classes, at least as measured on IQ tests, drop out almost as often as those who are less capable. Persistence, engagement, and motivation seem more crucial than intellectual ability alone (Archambault et al., 2009; Tough, 2012).

An added complication is that adolescents themselves vary: Some are thoughtful, some are impulsive, some are ready for analytic challenges, some are egocentric. All of them, however, need personal encouragement.

A study of student emotional and academic engagement from the fifth to the eighth grade found that, as expected, the overall average was a slow and steady decline of engagement. However, about 18 percent were highly engaged throughout while about 5 percent dramatically reduced engagement year by year (Li & Lerner, 2011). The 18 percent do well in high school. The 5 percent usually drop out, but some of them are late bloomers who could succeed in college if given time and encouragement. Thus, schools and teachers need many strategies if they hope to reach every adolescent.

Now let us seek practical, general conclusions for this chapter. The cognitive skills that boost national economic development and personal happiness are creativity, flexibility, relationship building, and analytic ability. Whether or not an adolescent is college-

SUMMING UP Worldwide, nations realize that high school education adds to national health and wealth, and thus many nations have increased the number of students in high schools. The United States is no longer the leader in the rate of high school graduation.

Middle schools tend to be less personal, less flexible, and more tightly regulated than elementary schools, which may contribute to a general finding: declining student achievement. Teachers grade more harshly, students are more rebellious, and because teachers specialize in a particular subject, every teacher has far more students overall than the typical primary school teacher. All of this works against what young adolescents need most, an adult who cares about their personal education.

Ideally, secondary education advances formal operational thinking, but this is not always the case. Variations in the structure of testing in high schools are vast, nationally and internationally. On international tests and measures, the United States is far from the top. Most high school graduates try college, but many do not graduate. The idea that high schools should prepare students to enter the workforce is controversial, with college attendance and then graduation the goal for many, but not the reality.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 15.21

Why have most junior high schools disappeared?

The age of puberty onset has decreased, shifting the appropriate age groupings for adolescents. Junior high has been replaced with middle school, and ninth grade has moved into the high school.Question 15.22

What characteristics of middle schools make them more diffi cult for students than elementary schools?

Having different teachers for each subject can make middle school teachers seem impersonal and distant; unlike elementary school, no one teacher is aware of a student's overall academic performance and social behavior. Changing classes for each period can make personal recognition from authority figures difficult at a time when such recognition is important. This can contribute to students developing a feeling of alienation from school and teachers. Students already at risk for emotional problems may react to the transition by experiencing intense anxiety or depression.Question 15.23

Why does puberty affect a person’s ability to learn?

For many middle school students, as academic achievement slows down, behavioral problems arise. Puberty itself is part of the problem. At least for other animals, especially when under stress, learning slows down at puberty.Question 15.24

How do beliefs about intelligence affect motivation and learning?

If they hold to the entity theory of intelligence, students believe that nothing they do can improve their academic skill. Entity belief can reduce motivation and learning. If they hold to the incremental theory of intelligence, students believe that effort is important to achievement. Incremental belief is associated with higher motivation and learning.Question 15.25

What are the advantages and disadvantages of high-

stakes testing? The effect of such tests on education is in dispute. High school graduation rates in the United States are inching upward, with 72 percent of ninth–grade students staying in school to graduate four years later. The concern is that those who do not graduate become very discouraged about education and the tests may, in fact, have a negative impact on continuing education. Research also shows that too much testing reduces overall learning rather than increasing it. Question 15.26

What are the problems with Advanced Placement classes and tests?

Some students are discouraged from taking the AP exams, and those who avoid taking AP classes are often African or Latino American. Some students who might pass do not enroll—because the class is not offered, the student is not motivated or encouraged, or the cost of the test is prohibitive. Another problem is that taking an AP class does not necessarily lead to college readiness. One study showed that overall, almost a third of those who took the exam failed. Failure rates were higher among African Americans, lower among Latino and Asian Americans. Question 15.27

Should high schools prepare everyone for college? Why or why not?

Overall, the data concerning college preparation presents a dilemma for educators. Suggesting that a student should not go to college may be racist, classist, sexist, or worse. On the other hand, many students who begin college do not graduate, so they lose time and gain debt when they could have advanced in a vocation. Everyone agrees that adolescents need to be educated for life as well as employment, but it is difficult to decide what that means.Question 15.28

How does the PISA differ from other international tests?

The PISA measures the students' ability to use skills they learned in school to cope with real–life problems, rather than testing facts as the TIMSS does.