Drug Use and Abuse

Hormonal surges, the brain’s reward centers, and cognitive immaturity make adolescents particularly attracted to the sensations produced by psychoactive drugs. But their immature bodies and brains make drug use especially hazardous.

Variations in Drug Use

Most teenagers try psychoactive drugs, that is, drugs that activate the brain. Cigarettes, alcohol, and many prescription medicines are as addictive and damaging as illegal drugs such as cocaine and heroin.

Age Trends

For many developmental reasons, adolescence is a sensitive time for experimentation, daily use, and eventual addiction to psychoactive drugs (Schulenberg et al., 2014). Both prevalence and incidence of drug use increase from about ages 10 to 25 and then decreases, as adult responsibilities and experiences make drugs less attractive.

Video: Risk-taking in Adolescence: Substance UseGANG LIU/SHUTTERSTOCK

Most worrisome is drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes before age 15, because early use escalates. That makes depression, sexual abuse, bullying, and later addiction more likely (Merikangas & McClaire, 2012; Mennis & Mason, 2012).

Although drug use increases as adolescents mature, we need to mention one exception: inhalants (fumes from aerosol containers, glue, cleaning fluid, etc.). Sadly, the youngest adolescents are most likely to try inhalants, because they find it easy to get and they are least able, cognitively, to understand the risk of one time use—

Variations by Place, Generation, and Gender

Nations vary markedly. Consider the most common drugs: alcohol and tobacco.

Especially for Police Officers You see some 15-

Avoid both extremes: Don’t let them think this situation is either harmless or serious. You might take them to the police station and call their parents. These adolescents are probably not life-

In most European nations, alcohol is part of every dinner, and children as well as adults partake. The opposite is true in much of the Middle East, where alcohol is illegal and teenagers almost never drink. The only alcohol available is concocted illegally; it is dangerous—

Cigarettes are available everywhere, but national differences are dramatic. In many Asian nations, anyone anywhere may smoke cigarettes; in the United States, adolescents are forbidden to buy or smoke, and smoking by anyone of any age is prohibited in many places. Nonetheless, 48 percent of U.S. high school seniors have tried smoking (MMWR, June 13, 2014).

In Canada, cigarette advertising is outlawed. Cigarettes packs have graphic pictures of diseased lungs, rotting teeth, and so on; fewer Canadian 15-

Variations within nations are also marked. In the United States, three-

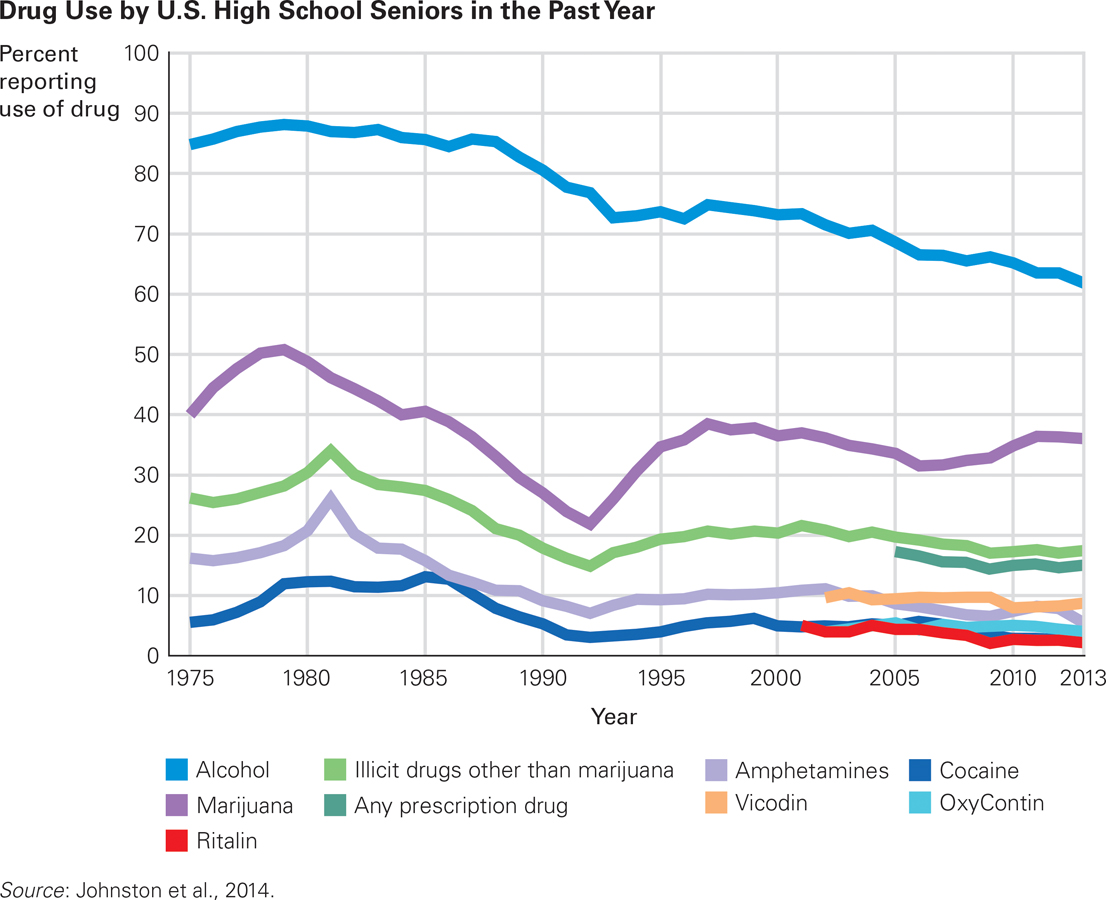

Cohort differences are evident, even over a few years. Use of most drugs has decreased in the United States since 1976 (see Figure 16.6), with the most notable decreases in marijuana and the most recent decreases in synthetic narcotics and prescription drugs (Johnston et al., 2014). As mentioned in Chapter 1, vaping (using e-

Rise and Fall By asking the same questions year after year, the Monitoring the Future study shows notable historical effects. It is encouraging that something in society, not in the adolescent, makes drug use increase and decrease and that the most recent data show a decline in use. However, as Chapter 1 emphasized, survey research cannot prove what causes change.

Longitudinal data show that the availability of drugs does not have much impact on use: Most high school students say they could easily get alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana if they wish. However, perception of risks varies from cohort to cohort, and that has a large effect on use.

With some exceptions, adolescent boys use more drugs and use them more often than girls do, especially outside the United States (Mennis & Mason, 2012). In Asia and South America, about four times as many boys as girls smoke. Although the exact proportion varies by nation, in Asia adolescent girls never smoke nearly as much as boys (Giovino et al., 2012).

These gender differences are reinforced by social constructions about proper male and female behavior. In Indonesia, for instance, 38 percent of the boys smoke cigarettes, but only 5 percent of the girls do. One Indonesian boy explained, “If I don’t smoke, I’m not a real man” (quoted in Ng et al., 2007).

In the United States, females smoke cigarettes about as often as males (for high school seniors the rates of smoking in the past month are 19 and 20 percent, respectively), but they drink alcohol at younger ages (MMWR, June 13, 2014). Body image is important for both sexes, which is why boys use more steroids and girls use more diet drugs. (Developmental Link: Body image is discussed in Chapter 14.)

Harm from Drugs

Many researchers find that drug use before maturity is particularly likely to harm body and brain growth, as well as predict addiction. However, adolescents typically deny that they ever could become addicted. Few adolescents notice when they move past use (experimenting) to abuse (experiencing harm) and then to addiction (needing the drug to avoid feeling nervous, anxious, sick, or in pain).

Each drug is harmful in a particular way. An obvious negative effect of tobacco is that it impairs digestion and nutrition, slowing down growth. This is true not only for cigarettes but also for bidis, cigars, pipes, and chewing tobacco, and probably e-

opposing perspectives

E-

Controversial is the use of e-

However, the fear is that adolescents who try e-

A victory of North American public health campaigns has been a marked reduction in smoking regular cigarettes. Not only are there only half as many adult smokers as there were in 1950, there are numerous public places where smoking is forbidden, and many people now forbid anyone to smoke in their homes.

In the United States, such homes were the majority (83 percent) in 2010, an increase from almost zero in 1970 and 43 percent in 1992. Many of those homes have no smoking residents, but cigarettes are banned at 46 percent of the homes where a smoker lives (MMWR, September 5, 2014). Adolescent smoking has markedly declined.

That is clearly a victory for public health, one to celebrate. Therein lies the danger. If e-

The argument from distributers of e-

Especially for Parents Who Drink Socially You have heard that parents should allow their children to drink at home, to teach them to drink responsibly and not get drunk elsewhere. Is that wise?

No. Alcohol is particularly harmful for young brains. It is best to drink only when your children are not around. Children who are encouraged to drink with their parents are more likely to drink when no adults are present. Adolescents are rebellious, and they may drink even if you forbid it. But if you allow alcohol, they might rebel with other drugs.

Alcohol is the most frequently abused drug in the United States. Heavy drinking impairs memory and self-

Adolescence is a particularly sensitive period, because the regions of the brain that are connected to pleasure are more strongly affected by alcohol during adolescence than at later ages. That makes teenagers less conscious of the “intoxicating, aversive, and sedative effects” of alcohol (Spear, 2013, p. 155). Brain damage by alcohol during adolescence has been proven with controlled research on mice, with the results seeming to extend to humans as well.

Marijuana seems harmless to many people (especially teenagers), partly because users seem more relaxed than inebriated. Yet adolescents who regularly smoke marijuana are more likely to drop out of school, become teenage parents, be depressed, and later be unemployed. Marijuana affects memory, language proficiency, and motivation—

Marijuana is often the drug of choice among wealthier adolescents, who then become less motivated to achieve in school and more likely to develop other problems (Ansary & Luthar, 2009). It seems as if, rather than lack of ambition leading to marijuana use, marijuana destroys ambition.

Twenty-

Some researchers wonder whether these are correlations, not causes. It is true that depressed and abused adolescents are more likely to use drugs, and that later these same people are likely to be more depressed and further abused. Maybe the stresses of adolescence lead to drug use, not vice versa.

However, longitudinal research suggests that drug use causes more problems than it solves, often preceding anxiety disorders, depression, and rebellion (Maslowsky et al., 2014). Further, adolescents who use alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana recreationally as teenagers are more likely to abuse these and other drugs after age 20 (Moss et al., 2014). Longitudinal studies of twins (which allow control for genetics and family influences) find that, although many problems predate drug use, drugs themselves add to the problems (Lynskey et al., 2012; Korhonen et al., 2012).

Most adolescents covet the drugs that slightly older youth use. Many 18-

New Zealand lowered the age for legal purchase of alcohol from 20 to 18 in 1999, and experienced more hospital admissions for intoxication, car crashes, and injuries from assault in both 18-

Preventing Drug Abuse: What Works?

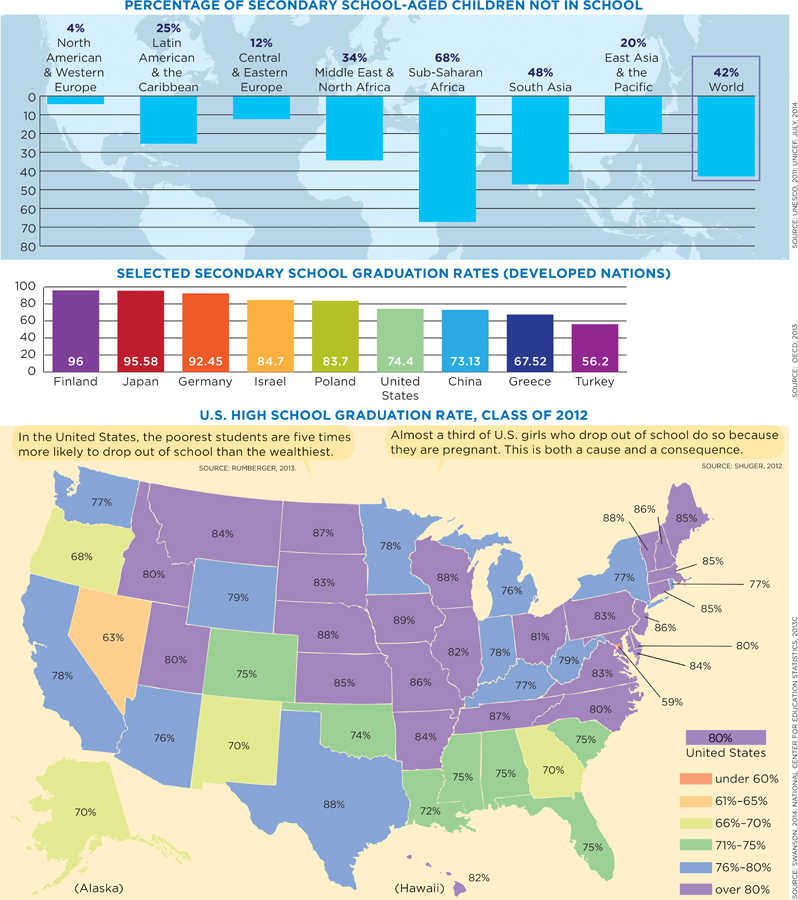

Drug abuse is progressive, beginning with a social occasion and ending alone. The first use usually occurs with friends; occasional use seems to be a common expression of friendship or generational solidarity. An early sign of trouble is lower school achievement, but few notice that as early as they should (see Visualizing Development, p. 536, for school dropout rates).

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

How Many Adolescents Are in School?

Attendance in secondary school is a psychosocial topic as much as a cognitive one. Whether or not an adolescent is in school reflects every aspect of the social context, including national policies, family support, peer pressures, employment prospects, and other economic concerns. Rates of teenage violence, delinquency, poverty, and pregnancy increase as school attendance decreases.

However, the Monitoring the Future study found that in 2013:

22 percent of high school seniors reported having had five drinks in a row in the past two weeks.

9 percent smoked cigarettes every day for the past month.

6.5 percent smoked marijuana every day.

[Johnston et al., 2014]

These figures are ominous, suggesting that addiction is the next step. Another problem is synthetic marijuana (“spice”), which was not widely available until 2009 and was used by 11 percent of high school seniors in 2012 (Johnston et al., 2014). And although prescription drug use may seem harmless since the source originally was a physician, many adolescents are addicted to prescription drugs.

Remember that most adolescents think they are exceptions, sometimes feeling invincible, sometimes extremely fearful of social disapproval, but almost never worried that they themselves will become addicts. They rarely realize that every psychoactive drug excites the limbic system and interferes with the prefrontal cortex.

Because of these neurological reactions, drug users are more emotional (varying from euphoria to terror, from paranoia to rage) than they would otherwise be. They are also less reflective. Moodiness and impulsivity are characteristic of adolescents, and drugs make them worse. Every hazard—

With harmful drugs, as with many other aspects of life, each generation prefers to learn things for themselves. A common phenomenon is generational forgetting, the idea that each new generation forgets what the previous generation learned (Chassin et al., 2014; Johnston et al., 2012). Mistrust of the older generation, added to loyalty to one’s peers, leads not only to generational forgetting but also to a backlash. When adults forbid something, that is a reason to try it, especially if the adolescent realizes that some adults exaggerated the dangers. If a friend passes out from drug use, adolescents may hesitate to get medical help.

Some antidrug curricula and advertisements actually make drugs seem exciting. Antismoking announcements produced by cigarette companies (such as a clean-

This does not mean that trying to halt early drug use is hopeless. Massive ad campaigns by public health advocates in Florida and California cut adolescent smoking almost in half, in part because the publicity appealed to the young. Public health advocates have learned that teenagers respond to graphic images. In one example:

A young man walks up to a convenience store counter and asks for a pack of cigarettes. He throws some money on the counter, but the cashier says “that’s not enough.” So the young man pulls out a pair of pliers, wrenches out one of his teeth, and hands it over…. A voiceover asks: “What’s a pack of smokes cost? Your teeth.”

[Krisberg, 2014]

Parental example and social changes also make a difference. Throughout the United States, higher prices, targeted warnings, and better law enforcement have led to a marked decline in cigarette smoking among younger adolescents. In 2012, only 5 percent of eighth-

Looking broadly at the past three chapters and the past 40 years in the United States, we see that universal biological processes do not lead to universal psychosocial problems. Sharply declining rates of teenage births and abortions (Chapter 14), increasing numbers graduating from high school (Chapter 15), and less misuse of legal and illegal drugs are apparent in many nations. Adolescence starts with puberty; that much is universal. But what happens next depends on parents, peers, schools, communities, and cultures.

SUMMING UP Most adolescents worldwide try drugs, most commonly cigarettes and alcohol. Drug use and abuse vary depending on age, culture, cohort, laws, and gender, with most adolescents in some nations using drugs that are never tried in other nations. Drug use early in adolescence is especially risky, since many drugs reduce learning and growth, harm the developing brain, and make later addiction more likely. Every cohort is offered new drugs, with e-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 16.27

Why are psychoactive drugs particularly attractive in adolescence?

Hormonal surges, the brain's reward centers, and cognitive immaturity make adolescents particularly attracted to the sensations produced by drugs.Question 16.28

Why are psychoactive drugs particularly destructive in adolescence?

Adolescents' immature bodies and brains make drug use especially hazardous. Many researchers find that drug use before maturity is particularly likely to harm body and brain growth. However, adolescents are especially likely to deny that they ever could become addicted to drugs. Few adolescents notice when they or their friends move past use to abuse and then to addiction. Each drug is harmful in a particular way. Psychoactive drugs can damage the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, both of which are still developing during adolescence. In addition, the younger the adolescent user, the less likely he or she is to comprehend the risks related to drug abuse. Cigarettes, alcohol and, prescription medicines can be as addictive and damaging as marijuana, cocaine, and heroin.Question 16.29

What specific harm occurs with tobacco products?

An obvious negative effect of tobacco products is that they impair digestion and nutrition, slowing down growth. This is true not only for cigarettes but also for bidis, cigars, pipes, and chewing tobacco, and probably e–cigarettes. Since internal organs continue to mature after the height spurt, drug– using teenagers who appear to be fully grown may damage their developing hearts, lungs, brains, and reproductive systems. Question 16.30

Why are developmentalists particularly worried about e-

cigarettes? Developmentalists are concerned that e–cigarettes may lead adolescents to become addicted to nicotine. In addition, e– cigarettes likely result in similar negative outcomes as other tobacco products— impaired digestion and nutrition, slowing down of growth, and damage to the heart, lungs, brain, and reproductive system. Question 16.31

What methods to reduce adolescent drug use are successful?

Massive ad campaigns by public health officials have been shown to decrease adolescent smoking by almost half. Parental example and social changes also make a difference. Throughout the United States, higher prices, targeted warnings, and better law enforcement have led to a marked decline in cigarette smoking among younger adolescents. In 2012, only 5 percent of eighth-graders had smoked cigarettes in the past month, compared with 21 percent in 1996.