Understanding How and Why

The science of human development seeks to understand how and why people—

Each aspect of this definition above merits explanation.

The Need for Science

Developmental study is a science. It depends on theories, data, analysis, critical thinking, and sound methodology, just like every other science. All scientists ask questions and seek answers in order to ascertain “how and why.” In this process, scientists gather evidence on whatever they are studying, be it chemical elements, rays of light, or, here, child behavior.

One hallmark of the science of human development is that it is interdisciplinary; that is, scientists from many academic disciplines (biology, psychology, sociology, anthropology, economics, and history among them) contribute to our understanding of how and why people grow.

Science is especially useful when we study children: Lives depend on it. What should pregnant women eat and drink? How much should babies cry? When and how should children be punished? What should 5-

People have disagreed about almost every question in child development—

The Scientific Method

To discard unexamined opinions and to rein in personal biases, we follow the five steps of the scientific method (see Figure 1.1):

Process, Not Proof Built into the scientific method—

Begin with curiosity. On the basis of theory, prior research, or personal observation, pose a question.

Develop a hypothesis. Shape the question into a hypothesis, a specific prediction to be examined.

Test the hypothesis. Design and conduct research to gather empirical evidence (data).

Page 5Analyze data and draw conclusions. Determine whether the evidence supports the hypothesis.

Report the results. Share the data, procedures, statistics, conclusions, and alternative explanations.

The Need for Replication

As you see, scientists begin with curiosity and then seek the facts, drawing conclusions only after careful research. Replication—repeating the procedures and methods of a study with different participants—

This method is not foolproof. Scientists sometimes draw conclusions too quickly, misinterpret data, or ignore alternative perspectives, as discussed at the end of this chapter. Something that is valid for one group of children in one time and place may not be valid elsewhere or in another time. Scientists continually refine methods, question the conclusions drawn by others, and occasionally discover—

Always, however, asking questions and testing hypotheses by gathering data is the foundation of science; always, scientists seek facts, not untested assumptions.

The Nature–Nurture Controversy

A great puzzle of development—

The nature–

Some people believe that most traits are inborn, that children are innately good (“an innocent child”) or bad (“beat the devil out of them”). Others stress nurture, crediting or blaming parents, neighborhoods, drugs, or even food when someone is good or bad, a hero or a criminal.

Neither belief is accurate. The question is “how much,” not “which,” because both genes and the environment affect every characteristic: Nature always affects nurture, and then nurture affects nature. Even “how much” is misleading if it implies that nature and nurture each contribute a fixed amount (Eagly & Wood, 2013; Lock, 2013).

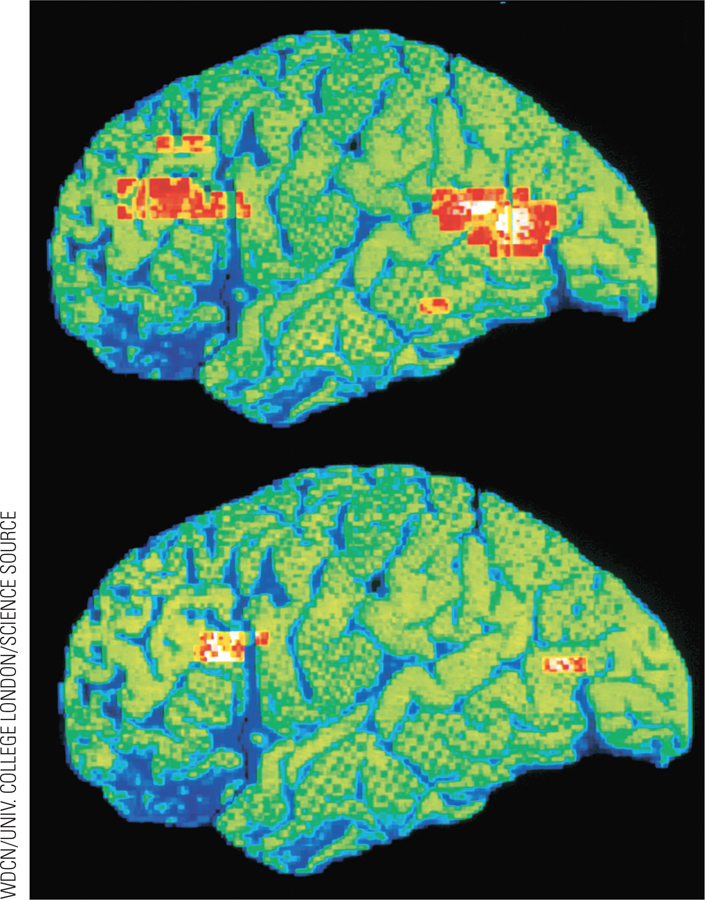

A complex nature–

Some People Are Vulnerable

Each aspect of nature and nurture depends on other aspects of nature and nurture, in ways that vary for each individual (Manuck & McCaffery, 2014). For instance, the negative impact of a beating, or of any other experience, might be magnified because of the particular versions of genes that a person has. The opposite is true as well: Some genes are protective, making people less vulnerable to difficult or traumatic experiences. Similarly, differences in nurture can either protect against or worsen the impact of a person’s genetic make-

For example, some people inherit genes (nature) for diabetes but never get that disease because nurture (in this case, diet and exercise) protects them. Or a person could be overweight and sedentary (both risk factors for diabetes and many other ailments) but never become diabetic because their genes buffer the effects of their habits.

Sometimes protective factors, in either nature or nurture, outweigh liabilities. As one review explains, “there are, indeed, individuals whose genetics indicate exceptionally high risk of disease, yet they never show any signs of the disorder” (Friend & Schadt, 2014, p. 970).

This is called differential susceptibility (or differential sensitivity)—that is, how sensitive a person is to any particular environmental experience differs from one person to another because of the particular genes each person has inherited. Some people are like dandelions—

For example, in one study, depression in pregnant women was assessed and then the emotional maturity of their children was measured. Those children who had a particular version of the serotonin transporter gene (5-

The Baby with Colic

An example of differential susceptibility comes from the 10 to 20 percent of all infants who cry for hours at a time in the first 3 months of life, presumably as a result of genes. They are said to have colic, and their frustrated parents cannot comfort them (J.S. Kim, 2011).

A colicky baby is like an orchid, and future development depends on nurture. For some, their inconsolable crying makes the parents unusually responsive. Then the children become better than average (more outgoing, generous, high–

One study of colicky babies confirms that parents react in many ways (Landgren et al., 2012). One mother said:

There were moments … when she was apoplectic and howling so much that I almost got this thought, ‘now I’ll take a pillow and put it over her face just until she quietens down, until the screaming stops.’

By contrast, another mother said:

In some way, it made me stronger, and made my relationship with my son stronger…. Because I felt that he had no one else but me. ‘If I can’t manage, no one can.’ So I had to cope.

As two developmental experts explain:

Differential susceptibility implies … that it may be mistaken to regard some children—

[Belsky & Pluess, 2012, p. 3]

These experts find that genetic vulnerability (in this case, the DRD4 gene) does not disappear. During adolescence even well-

The specifics of differential susceptibility require complex and extensive empirical data, as thousands of scientists seeks to understand exactly how nature and nurture interact to produce each particular human trait with each version of each gene. But the simple conclusion remains: Neither genes nor upbringing alone make a child amazingly good or incredibly bad (Masten, 2014). Both nature and nurture matter.

The Three Domains

Obviously, it is impossible to examine nature and nurture on every aspect of human development at once. Typically therefore, individual scientists study one characteristic at a time. A century ago, physical development (such as tooth eruption or running speed) was the main focus of developmental research, but scientists now realize that not only the body but also the intellect and emotions develop throughout life. To understand the whole person, an interdisciplinary approach to human development has replaced the old silo approach of the past.

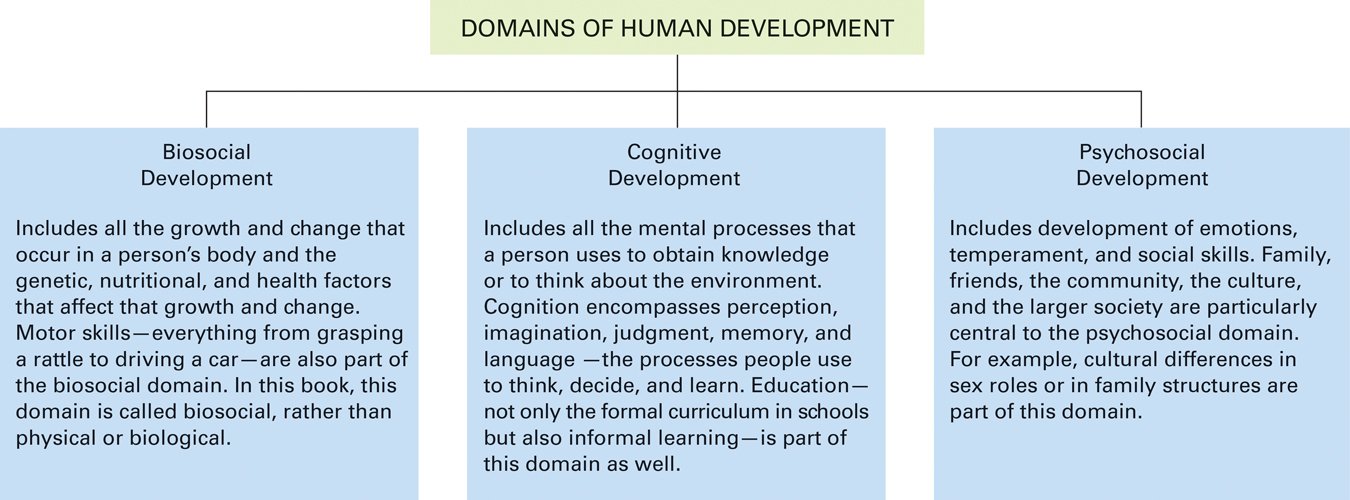

To make it easier to study, development is often considered in three domains—

The Three Domains The division of human development into three domains makes it easier to study, but remember that very few factors belong exclusively to one domain or another. Development is not piecemeal but holistic: Each aspect of development is related to all three domains.

However, since every person is a whole tapestry of multi-

This constant interaction of domains presents a problem: Words and pages follow in sequence and the mind thinks one thought at a time. That makes it impossible to describe or grasp all domains simultaneously. The scientific method weaves disparate threads together, as evidence-

Childhood and Adulthood

Are children more important than adults? For decades, because the focus of developmentalists was on physical growth, the answer to this question was yes. Consequently, the study of human development was the study of child development, with a nod to the physical declines of old age. That produced, as a famous critic described, “a curiously broken trajectory of knowledge … [with] a brave beginning, a sad ending, and an empty middle (Bronfenbrenner, 1977, p. 525).

Since people were not thought to develop over the years of adulthood, developmentalists did not study adults. The opposing giants of developmental theory, Sigmund Freud and Jean Piaget, agreed on one thing: The final stage of development began in early adolescence and then continued without significant change until death.

Recently, however, that empty middle has been filled. Scientists now gather data about adulthood, discovering many developmental changes. For example, sexual appetites, cognitive perspectives, and employment attitudes all change markedly from ages 15 to 65.

No one now thinks that development stops at age 15. Although many scholars still focus on one part of the lifespan, every developmentalist considers what happened before, and what will happen after, each particular period. For instance, one influential scholar believes infancy is “the foundation and catalyst of human development” (Bornstein, 2014, p. 121). In other words, he studies infancy to understand the rest of life.

Is childhood more important, influential, and determinative than adulthood? If a person is, say, malnourished from age 30 to 33, is that as harmful as if that same person had been malnourished from birth to age 3? The answer to that specific question is no. Neuroscientists have proven that early malnutrition can stunt brain growth and have long-

But scientists are not certain about the cognitive and psychosocial domains. If you had to choose only one developmental period in which to invest billions of education dollars, should you choose preschools or colleges? Or if you were a psychologist who wanted to treat people who would benefit most, would they be children or adults?

The answer is not obvious. Some research suggests that the first years of life are the most crucial for intellectual or emotional development, but other research finds the opposite: Educating parents, or even grandparents, may be the best way to help children. Some researchers find that the adolescent years are more pivotal for later development than those of early childhood (Falconi et al., 2014).

Political debates need solid data. Should the U.S. Congress protect fetuses and infants (e.g., WIC, mother/infant food supplements), or preschoolers (e.g. Head Start), or older children (e.g., public schools), or emerging adults (e.g., college subsidies), or employees (e.g., raising the minimum wage) or seniors (e.g., Social Security and Medicare)?

All of these age groups need help, but government programs are expensive. If we knew that a particular investment in one age group would have greater impact overall than the same money invested at another age, that would guide policy. But developmentalists disagree, even on who needs financial support most, much more on who most needs education, or family support. More science is needed. This leads us to the second phase of our definition.

SUMMING UP The scientific study of human development follows five steps: curiosity, hypothesis, data collection, conclusions, and reporting. Scientists build on prior studies, examining procedures and replicating results—

For instance, scientists no longer assume that development is either totally genetic or totally environmental. Instead, nature and nurture always interact, with variations between one person and another, as highlighted by differential susceptibility. Colic is one example.

The scientific method is followed within many disciplines and in all three domains—

Once developmental scientists focused almost exclusively on children. Then adult development was recognized. Now researchers seek to understand which interventions at what ages are most effective for optimal development.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 1.1

What makes the study of human development a science?

Just like every other science, developmental study depends on theories, data, analysis, critical thinking, and sound methodology.Question 1.2

Why is replication sometimes considered an essential follow-

up to the five steps of the scientific method? ReplicationReplication involves repeating a study, usually with different participants. Scientists learn from each other, building on what has gone before. They hesitate to draw conclusions or to believe the results of others' research until replication has occurred.Question 1.3

Why is it a mistake to ask whether a human behavior stems from nature or nurture?

Both genes and the environment affect every human characteristic: Nature always affects nurture, and nurture always affects nature.Question 1.4

Why are some children more affected by their environment than others?

Differential susceptibility is the idea that people vary in how sensitive they are to particular environmental experiences. Susceptibility differs from one child to the next because of the particular genes each person has inherited. Some people are like dandelions—hardy, growing and thriving in good soil or bad, with or without ample sun and rain. Others are like orchids— quite wonderful but only when ideal growing conditions are met. Question 1.5

What is the difference between each of the three domains—

biosocial, cognitive, and psychosocial? The biosocial domain includes all of the growth and change that occur in a person's body and the genetic, nutritional, and health factors that affect that growth and change. The cognitive domain includes all the mental processes that a person uses to obtain knowledge or to think about the environment. The psychosocial domain includes development of emotions, temperament, and social skills.Question 1.6

Why do some people believe that the years of childhood are more crucial for development than the years of adulthood?

For decades, because the focus of developmentalists was on physical growth, many believed that the childhood years were more crucial for development than the adulthood years. Today, researchers recognize the importance of child, adolescent, and adult development.