Including All Kinds of People

Developmentalists study everyone—

Difference or Deficit?

One reason to study people of all kinds is to combat the human inclination to think that anyone who is different is also deficient, i.e., lacking in something that is important for a good life. We are amused when young girls say, “Boys stink,” or their male classmates say, “Girls are stupid,” but adults have the same tendency: to judge people unlike themselves as inferior.

For example, although males and females are similar in almost every trait, humans tend to look for sex differences, not similarities, and then to make sexist judgments. Most research finds far more similarities than differences between the sexes. One of the very few proven gender differences is that women are more tenderhearted and men more sexually driven (Hyde, 2014). If you are male, do you think that women are weak because they are too emotional; if you are female, do you think men are too obsessed with sex? If you answer yes, how human of you. And how wrong.

Negative judgments are too readily made about people who raise their children differently or who believe in an unfamiliar religion. Have you heard people criticize teenagers, middle-

The human tendency to observe differences and then conclude that people are inferior if they are unlike the observer is called the difference-

Sexual Orientation

The importance of accepting diversity is apparent when considering sexual orientation. Most teenagers are powerfully attracted to members of the other sex, but some—

Video: Research of Geoffrey SaxeFOOTAGE BY GEOFFREY SAXE

This perceived deficit led school bullies to target classmates thought to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) (Juvonen & Graham, 2014), and many LGBT teenagers themselves felt inferior. As a result, LGBT teenagers committed suicide at a much higher rate than did their heterosexual peers (Herek, 2010).

Over time, however, activism, scientific data, and other factors combined to cause a dramatic change in the culture. In the 1970s, psychiatrists and psychologists declared, “Homosexuality per se implies no impairment in judgment, stability, reliability” (Conger, 1975, p. 633), and by 2014, same-

As this difference is less assumed to be a deficit, serious depression and crippling anxiety among LGBT youth has become less common. This is true generally, as well as within each family and community, although certainly there are some areas and families that reject such teens. Their rate of psychological problems is half as high in jurisdictions with policies that indicate acceptance (e.g., laws against hate crimes) compared to communities where same-

Culture, Ethnicity, and Race

To include “all kinds of people” requires that researchers study children of many cultures, ethnicities, and races. Yet each of these three terms is often confused, by scientists as well as non-

Culture, ethnicity, and race are social constructions, which means that they are created by society. Social constructions are powerful, affecting thoughts and behavior (as evident with people’s ideas regarding sexual orientation), but since they arise from society, they can be changed by society. Because the study of development focuses on change over time, it is crucial that the fluidity and distinct meaning of each of these words be understood.

A System of Shared Beliefs

For social scientists, culture is “the system of shared beliefs, conventions, norms, behaviors, expectations and symbolic representations that persist over time and prescribe social rules of conduct” (Bornstein et al., 2011, p. 30). Culture is far more than eating certain foods or practicing certain rituals; it is a powerful social construction.

Each family, community, and college has a particular culture. For instance, Jamaicans in the United States are said to be tri-

OBSERVATION QUIZ How many children are sleeping here in this photograph?

Nine—

Furthermore, individuals within each culture sometimes rebel against their culture’s expected “beliefs, conventions, norms, behaviors.” Cultural influences must be recognized, but not slavishly: Culture is powerful, but also fluid and changing.

Watch Video: Interview with Barbara Rogoff to learn more about the role of culture in the development of Mayan children in Guatemala.

To appreciate that culture is a matter of beliefs and values, not superficial differences, consider language. Of course, people speak distinct languages, but that in itself is not a cultural difference. However, among some English-

One of my East Indian students remembered:

My mom was outside on the porch talking to my aunt. I decided to go outside; I guess I was being nosey. While they were talking I jumped into their conversation which was very rude. When I realized what I did it was too late. My mother slapped me in my face so hard that it took a couple of seconds to feel my face again.

[C., personal communication]

Notice that my student continues to reflect her culture; she labels her own behavior “nosey” and “very rude.” She later wrote that she expects children to be seen but not heard and that her own son makes her “very angry” when he interrupts.

As in this case, cultural values, learned in childhood, tend to persist even when the overall culture has shifted. Culture is not a straightjacket, however. In fact, many parents (including many of Asian ancestry) allow their children more freedom of expression than their parents allowed them. And many parents who have been in North America all their lives nonetheless teach their children not to interrupt adults.

Heritage

People of an ethnic group share certain attributes, almost always including ancestral heritage and usually national origin, religion, and language (Whitfield & McClearn, 2005). Ethnic group is not the same as cultural group: People of a particular ethnicity need not share a culture (compare people of Irish descent in Ireland and in Illinois), and some cultures include people of several ethnic groups (consider British culture).

Ethnicity is a social construction, affected by the social context. For everyone, ethnic identity is strengthened if (1) other members of the same group are nearby, and (2) other groups consider the person an outsider. Thus, ethnicity depends partly on context.

For example, people born in Africa who are longtime residents of North America typically consider themselves African, unless they are with many other African-

Similar particular identities are evident everywhere: Ethnic identity becomes more specific and more salient (Sicilian, not just Italian; South Korean, not just East Asian) under certain circumstances. Many Americans are puzzled by distant civil wars (e.g., in Syria, or Sri Lanka, or the Ukraine) because people who look alike seem to be bitter enemies. However, those on opposing sides see many ethnic differences between them.

Physical appearance is sometimes a marker for ethnicity. The most visible example is skin color, often taken to indicate race. However, race is also a social construction—

opposing perspectives*

*

Using the Word Race

The term race is used to categorize people via physical markers, particularly outward appearance. Historically, most North Americans believed that race was the outward manifestation of inborn biological differences. Fifty years ago, races were categorized by skin color: white, black, red, and yellow (Coon, 1962).

It is obvious now, but was not a few decades ago, that no one’s skin is really white or black or red or yellow. Social scientists are convinced that race is a social construction, that society used color terms to exaggerate differences in skin tones.

Genetic analysis confirms that the biological concept of race is inaccurate. Although most genes are identical in every human, those few genetic differences that distinguish one person from another are poorly indexed by appearance (Race, Ethnicity, and Genetics Working Group of the American Society of Human Genetics, 2005).

Skin color is particularly misleading because dark-

Race is more than a flawed concept; it is a destructive one. It is used to justify racism: Slavery, lynching, and segregation were directly connected to the conviction that race was inborn. Racism continues today in less obvious ways (some highlighted later in this book), impeding the goal of our study—

Since race is a social construction that leads to racism and distracts us from recognizing other social problems, some social scientists believe that the term should be abandoned (Gilroy, 2000). It is no longer used in many nations.

A study of 141 nations found that 85 percent never use the word race on their census forms (Morning, 2008). Only in the United States does the census still distinguish between race and ethnicity, stating that Hispanics “may be of any race.”

Because of the way human cognition works, such labels encourage stereotyping (Kelly et al., 2010). As one scholar explains:

The United States’ unique conceptual distinction between race and ethnicity may unwittingly support the longstanding belief that race reflects biological difference and ethnicity stems from cultural difference. In this scheme, ethnicity is socially produced but race is an immutable fact of nature. Consequently, walling off race from ethnicity on the census may reinforce essentialist interpretations of race and preclude understanding of the ways in which racial categories are also socially constructed.

[Morning, 2008, p. 255]

Perhaps to avoid racism, the word race should not be used.

But consider the opposite perspective (Bliss, 2012). In a society with a history of racial discrimination, reversing that cultural heritage may require recognizing race. Although race is a social construction, not a biological distinction, it is powerful nonetheless. Particularly in adolescence, people who are proud of their racial identity are likely to achieve academically, resist drug addiction, and feel better about themselves (Crosnoe & Johnson, 2011; Zimmerman et al., 2013).

Many medical, educational, and economic conditions—

Indeed, many social scientists argue that pretending that race does not exist allows racism to thrive (e.g., sociologists Marvasti & McKinney, 2011; anthropologist McCabe, 2011). Two political scientists studying criminal justice found that people who claim to be color-

According to some scholars the election of President Obama revealed racial prejudice, and uninformed anti-

Socioeconomic Status

Some social scientists believe that when studying “all kinds of people,” differences in socioeconomic status (SES) are more potent than cultural or ethnic differences. SES affects every moment of development, from whether or not a zygote is conceived (rates of sexual activity and contraception vary by SES) to when a person dies (wealthy people live longer).

Like culture, ethnicity, and race, SES is a complicated category. Income is part of socioeconomic status, but only part: For children, their neighborhood and their parents’ level of education is often more influential. This is reflected when people speak of social class, as in “the shrinking middle class” or “working class values.” Such phrases imply habits and attitudes as much as income (Stephens et al., 2012).

Consider a U.S. family comprised of an infant, an unemployed mother, and a father who earns $18,000 a year. Their SES would be low if the wage earner were an illiterate dishwasher living in an urban slum, but it would be high if the wage earner were a PhD student living on campus and teaching part-

However, when governments categorize people they rely almost exclusively on income. The U.S. federal poverty line is based primarily on food cost and family size. That standard was set in 1965 and is still used, although economists find that shelter and medical costs are better indicators of income adequacy than food. According to 2014 federal cutoffs, a household of three people with a combined annual income under $19,790 (in Alaska, $24,730) is officially poor.

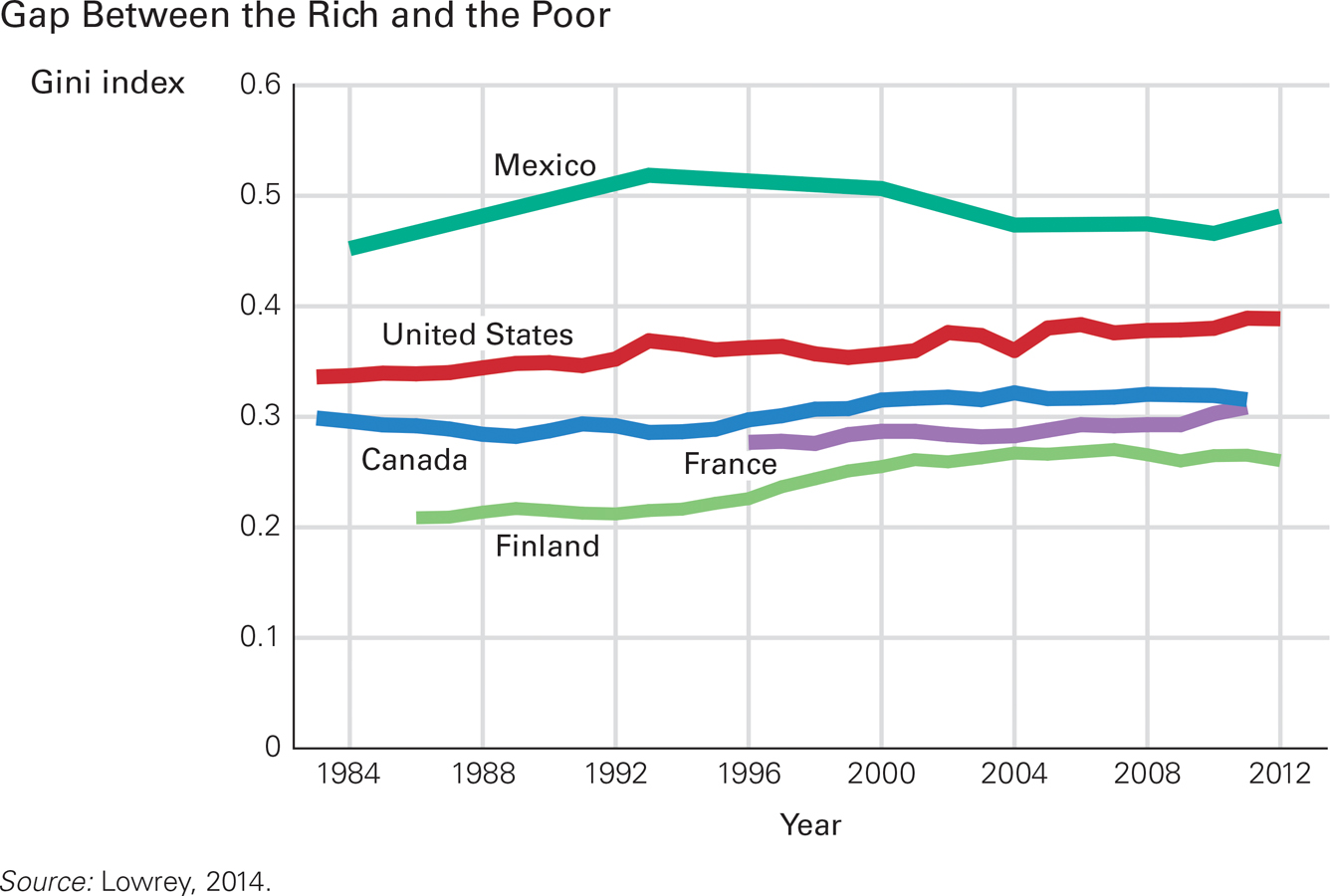

The Rich Get Richer The Gini index is a measure of income equality, ranging from zero (everyone equal) to one (one person has all the money). Values here are after taxes, which shows that the gap between rich and poor is widening in the United States and Finland but not in other countries. Worldwide, the gap between the richest people and the poorest is even wider, estimated at about 0.63 on the Gini.

Policies and practices regarding poverty vary from nation to nation. In the United States, the gap between rich and poor, and between young and old, has increased in the past three decades (Lowrey, 2014) (see Figure 1.3). That has resulted in increased disparities in health, education, and neighborhood between those at the top and bottom.

For example, the life expectancy gap between the rich and poor has widened in the United States. Wealthy people live about six years longer than they did thirty years ago, but poor people die at almost the same age, on average, as their parents did.

SES affects almost every aspect of life in every nation and in every region of each nation, as illustrated in Visualizing Development (see the inside cover). That fact is known to everyone who examines the data, although not everyone agrees about the specifics or the implications (Chambers et al., 2014).

Finding the Balance

All humans are the same. Yet as sex, culture, ethnicity, and SES make clear, every group is different. Furthermore, genetically each individual is unique. Is that a paradox, a dilemma, or a challenge? How general, and how specific, should developmentalists be? A leading scholar wrote:

Psychologists and psychiatrists are fond of writing sentences such as “individuals with the short allele of the serotonin transporter [the 5-

[Kagan, 2011, p. 111]

Kagan’s suggestion is meant to be an exaggeration: The right balance between generalizations and specifics is not obvious, but Kagan insists that developmental conclusions should never be “contextually naked” (2011, p. 112). In other words, variations in background and circumstances should always be considered. Not only are neither nature nor nurture determinative, but also making simple predictions, across or within groups, is a mistake.

Both dismissing the impact of SES, culture, and so on, and taking it too much to heart, are mistakes. One of my students did the former, saying, “That’s just a statistic, it doesn’t apply to me,” and another did the latter, saying “Now that I know all the risks for a woman like me, I will never have children.” I tried to dissuade them both.

Remember that differences are not necessarily deficits, racial and ethnic categories are social constructions, and income does not trump education. Yet all differences, categories, and incomes have an effect on everyone, an effect that is neither intractable nor irrelevant. Effects change over time. This leads to the third aspect of our definition.

SUMMING UP Persons of every age, culture, and background teach us what is universal and what is unique in human development. Differences among people are not necessarily deficits, although some people mistakenly assume that their own path and choices are best for everyone.

Each person grows up with an ethnic identity and within several cultures. As social constructions, culture and ethnicity can change, but they have an impact. Race is no longer considered a biological category, but it is nonetheless a potent factor in development. Finally, socioeconomic status, which includes parents’ income and education, powerfully affects the development of a child: SES affects medical care, schooling, and neighborhood, each shaping every child’s body and brain. Taking all the contextual influences on child development into account, while recognizing that each child is unique, not determined by their SES or any social construction, is a challenge for developmentalists.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 1.7

How are opinions on sexual orientation an example of the difference-

equals- deficit error? The difference–equals– deficit error is the human tendency to observe differences and then conclude that people are inferior if they are unlike the observer. Because some teenagers (fewer than 1 in 20) are attracted to people of their own sex, they can be perceived as inferior, leading to discrimination and bullying. Question 1.8

How can cultural values been seen as a social construction?

Similar to ethnicity and race, cultural values are a social construction, which means they are created by society. Specifically, culture is the system of shared beliefs, conventions, norms, behaviors, expectations, and symbolic representations that persist over time and prescribe social rules of conduct.Question 1.9

What is the relationship between ethnic group and culture?

Ethnic group is not the same as cultural group: People of a particular ethnicity need not share a culture (for example, compare people of Irish decent in Ireland and in Illinois), and some cultures include people of several ethnic groups (for example, consider British culture).Question 1.10

Why is it more useful to consider ethnicity and culture instead of the differences in appearance that are used to indicate race?

Race is a social construction and a misleading one. Historically, society has used color terms to exaggerate differences in skin tones. It has also been used to justify racism. Considering ethnicity and culture is a less biased approach than judging people on the basis of skin color.Question 1.11

What factors are used to indicate a person’s SES?

Socioeconomic status (SES) includes one's income, occupation, education, and place of residence.