Cautions and Challenges from Science

The scientific method illuminates and illustrates human development as nothing else does. Facts, hypotheses, and possibilities have all emerged that would not be known without science—

For example, infectious diseases in children, illiteracy in adults, depression in late adulthood, and racism and sexism at every age are much less prevalent today than a century ago. Science deserves credit for all these advances. Even violent death is less likely, with scientific discoveries and universal education considered likely reasons (Pinker, 2011).

Developmental scientists have also discovered unexpected sources of harm. Video games, cigarettes, television, shift work, and asbestos are all less benign than people first thought. Although the benefits of science are many, so are the pitfalls. We now discuss three potential hazards: misinterpreting correlation, depending too heavily on numbers, and ignoring ethics.

Correlation and Causation

Probably the most common mistake in interpreting research is confusing correlation with causation. A correlation exists between two variables if one variable is more—

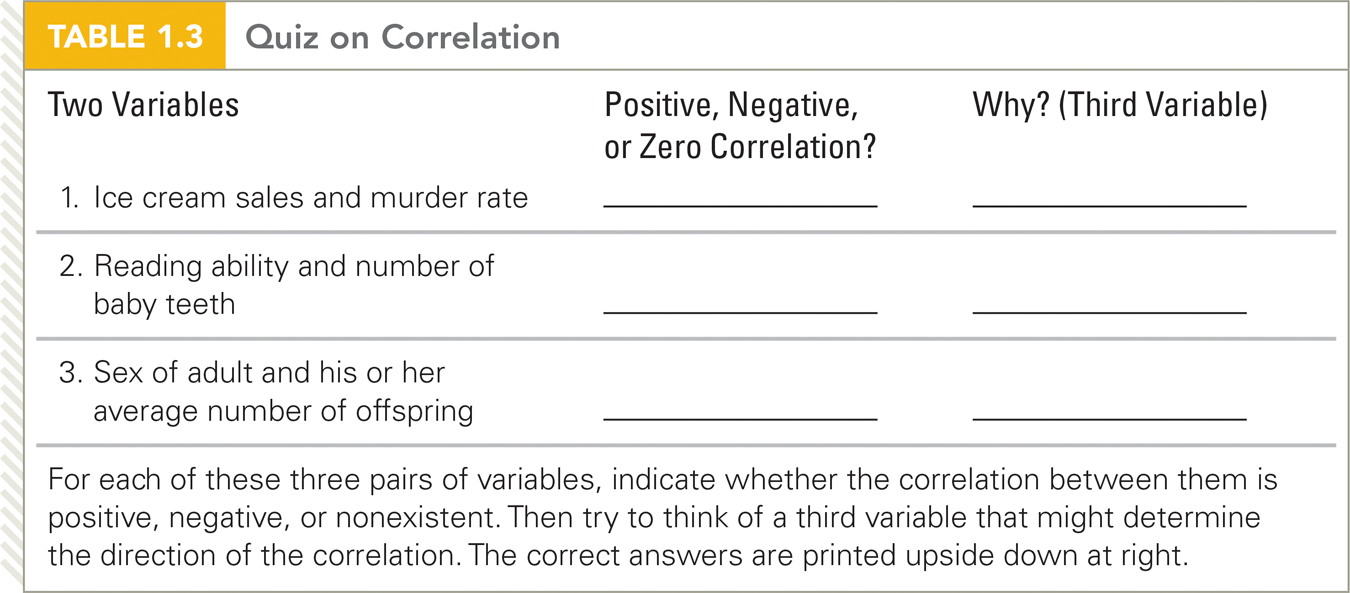

To illustrate: From birth to age 9, there is a positive correlation between age and height (children grow taller as they grow older), a negative correlation between age and napping (children nap less often as they grow older), and zero correlation between age and number of toes (children do not grow new toes with age). (Now try the quiz on correlation in Table 1.3.)

Positive; third variable: heat

Negative; third variable: age

Zero; each child must have a parent of each sex; no third variable

Many correlations are unexpected. For instance, first-

However, correlation is not causation. Just because two variables are correlated does not mean that one causes the other—

Many mistaken and even dangerous conclusions are drawn because people misunderstand correlation, as the following A View from Science explains.

a view from science*

Vaccination and Autism

The most recent confusion of correlation and causation regards autism spectrum disorders. Generally, the first signs of autism occur early in life, when a parent notices something wrong with how their baby responds to people. For instance, the infant might not smile, laugh, or even listen to voices or look at faces the way most babies do. Then talking is delayed, abnormal, or even absent, and the baby cries at sensations that don’t bother most infants.

Thirty years ago some psychologists blamed mothers’ child care for autism (the “refrigerator mom”) but now most experts believe something genetic or prenatal disrupted normal social connections in the brain. That implies either that the parents carry the genes for autism or that the mother harmed the fetal brain when she was pregnant, or both (Persico & Merelli, 2014). Understandably, some parents seek a cause elsewhere. Among the possibilities are pollution, pesticides, or drugs administered during birth. But the easiest target has been immunization.

From birth to 18 months, the United States Centers for Disease Control recommends that babies get 25 doses of vaccine, sometimes in combination such as MMR (mumps, measles, and rubella) and DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis). As a result, when a parent first notices symptoms of autism, almost always she or he will remember a recent immunization.

Another correlation is evident: The rate of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders has risen dramatically over the past two decades, from about one child in a thousand to one in 88, and the number of vaccines has risen as well. Many parents are convinced that this proves causation.

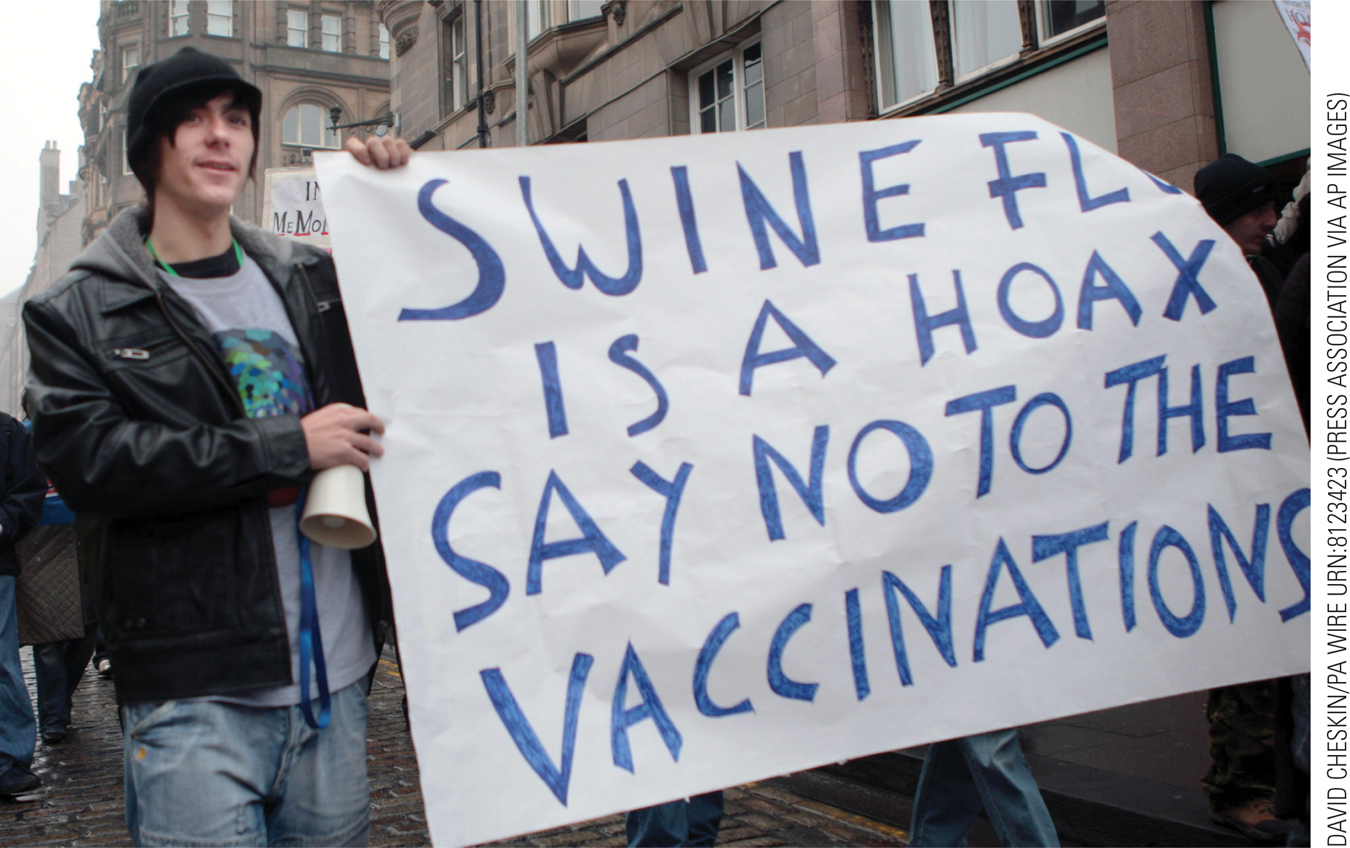

No scientist who has examined the evidence agrees. But a decade ago, state legislators heeded the fears of their constituents to allow some parents to enroll their children in school without required immunization. Every U.S. state allows some parents to refuse to vaccinate their children for medical reasons (two states), for medical or religious reasons (29 states), or for medical, religious, or personal belief reasons (19 states).

Colorado and California have the most unvaccinated children (about 20 percent) and the highest rates of childhood diseases. In 2010, California had an epidemic of whooping cough (pertussis). Ten babies died (Seppa, 2014).

That horrifies some doctors and scientists (Offit, 2011). Immunization is a major reason that 99 percent of all infants in developed nations survive at least until adolescence, compared to the nineteenth century when half of all babies died. That also illustrates why the scientific method is so important.

Fearful parents do not deserve all the blame. Almost twenty years ago, the leading medical journal in England (the Lancet) published a study of 12 children by a British doctor, linking the MMR to autism (Wakefield et al., 1998). A flurry of research followed, but his results were not replicated—

By 2005, longitudinal, prospective, and retrospective studies of thousands of children in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Denmark found no correlation between vaccination and autism or any other disease (Andrews et al., 2004; Madsen et al., 2003; Institute of Medicine (U.S). Safety Review Committee, 2004). Since then, researchers confirmed that unvaccinated children are more likely to become seriously ill. The Wakefield study was “retracted,” which means that the editors of the Lancet found such faulty data collection that the conclusions are invalid.

Sadly, that does not convince all the parents. Suspicion of science and of the federal government has led to suspicion of vaccination. Fortunately, infectious diseases spread slowly if most children are immunized, a phenomena called “herd immunity.” As a result, even non-

Unfortunately, if immunization rates fall lower than about 90 percent, social protection wanes. That explains why five times as many U.S. children had measles in 2014 than in the average of the previous 15 years. As fewer children are immunized, more will contract measles, chickenpox, mumps, or other preventable diseases. Even some immunized children will get sick, because no vaccine is always effective.

The other tragedy is that fewer research dollars will be spent on finding the genes and toxins that cause autism. Too many parents misunderstand correlation and causation, and then try to protect their own child while increasing the risk for everyone.

Ethics

Video Activity: Eugenics and the Feebleminded: A Shameful History illustrates what can happen when scientists fail to follow a code of ethics.

The most important caution for all scientists, especially for those studying humans, is to uphold ethical standards in their research. Each academic discipline and every professional society involved in the study of human development has a code of ethics (a set of moral principles) delineating specific practices to protect the integrity of research.

Ethical standards and codes are increasingly stringent. In the United States, most educational and medical institutions have an Institutional Review Board (IRB), a group that permits only research that follows certain guidelines. IRBs often slow down scientific study, but they are necessary: Some research conducted more than 50 years ago, before IRBs were established, was clearly unethical, especially when the participants were children, members of minority groups, prisoners, or animals (Blum, 2002; Washington, 2006).

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Diverse Complexities

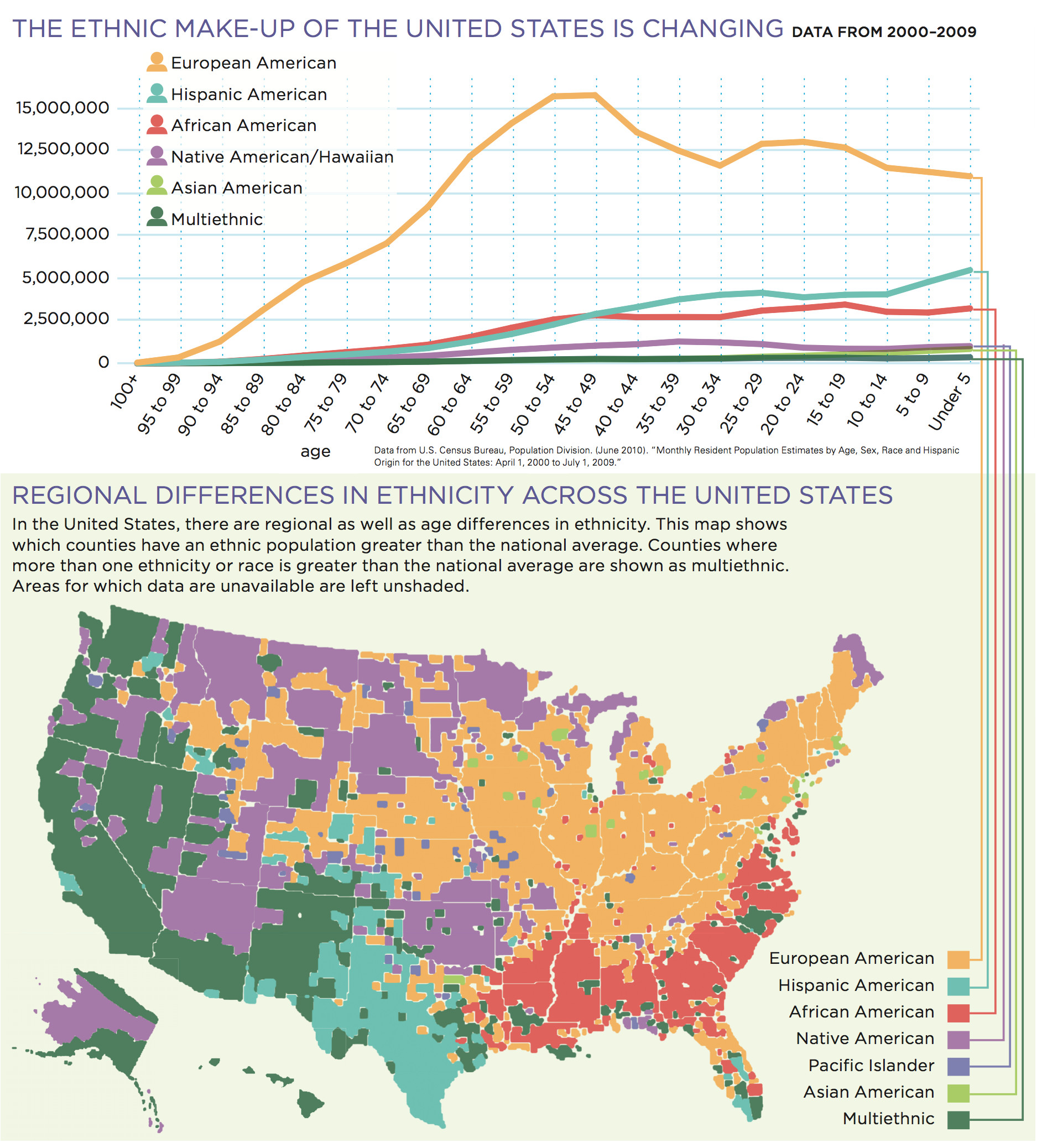

It is often repeated that “the United States is becoming more diverse,” a phrase that usually refers only to ethnic diversity and not to economic and religious diversity (which are also increasing and merit attention). From a developmental perspective, two other diversities are also important—

Scientists—

Protection of Research Participants

Especially for Future Researchers and Science Writers Do any ethical guidelines apply when an author writes about the experiences of family members, friends, or research participants?

Yes. Anyone you write about must give consent and be fully informed about your intentions. They can be identified by name only if they give permission. For example, family members gave permission before anecdotes about them were included in this text. My nephew David read the first draft of his story (see page 21) and is proud to have his experiences used to teach others.

The most important safeguards are those that ensure no one is harmed by the study. Participation must be voluntary and confidential. This entails the informed consent of the participants—

When the study is over, the participants must be “debriefed”—told what the study was about and what the results were.

Integrity of Scientific Study

Scientists are obligated to “promote accuracy, honesty, and truthfulness” (American Psychological Association, 2010) in their methods and conclusions.

Deliberate falsification is unusual. When it does occur, it leads to ostracism from the scientific community, dismissal from a teaching or research position, and, sometimes, criminal prosecution. This occurred recently with Diederik Stapel, a Dutch social psychologist. He created data that was not actually collected. Unfortunately, he is one of several prominent scientists, in both the physical and the social sciences, who have committed fraud. Almost always, other scientists are the first to notice the deception and sound the alarm (W. Stroebe et al., 2012).

Another obvious breach of ethics is to “cook” the data, or distort one’s findings, in order to make a particular conclusion seem to be the only reasonable one. This is not as rare as it should be. Tenure, promotion, and funding all encourage scientists to publish, and publishers seek remarkable findings. Awareness of this danger is leading to increased calls for replication (Carpenter, 2012).

Scientists are rewarded for publishing surprising results. When a hypothesis is not confirmed, that may lead to the “file drawer problem”; that is, a study is filed away and never published because the results are not exciting.

Ethical standards cannot be taken for granted. As stressed in the beginning of this chapter, researchers, like all other humans, have strong opinions, and they expect research to confirm their opinions. Therefore, sometimes without even realizing it, they might try to achieve the results they want. As one team explains:

Our job as scientists is to discover truths about the world. We generate hypotheses, collect data, and examine whether or not the data are consistent with those hypotheses…. [But we] often lose sight of this goal, yielding to pressure to do whatever is justifiable to compile a set of studies we can publish. This is not driven by a willingness to deceive but by the self-

[Simmons et al., 2011, pp. 1359, 1365]

Obviously, collaboration, replication, and transparency are essential ethical safeguards for all scientists.

Science as a Way to Help Humankind

Science can be a catalyst for social change, improving the lives of millions of people, as you will see often in this text. For example, the spread of preschool education, or the acceptance of children with disabilities, arose directly from research in child development.

In this chapter, changed attitudes about sexual orientation (page 22) and about marijuana (page 21) have followed new research on those topics. For both of these issues, and many others, the passions of people on opposite sides make evidence-

The ultimate purpose of the science of human development is to help “all kinds of people, everywhere, of every age” live satisfying and productive lives. Consider these questions:

Do we know enough about prenatal drug use to protect every fetus?

Do we know enough about poverty to enable everyone to be healthy?

Do we know enough about various family structures to understand the impact on children of marriage, or divorce, or single parenthood?

Do we know enough about television, video games, the Internet, and cell phones to use these to enhance learning, not harm children?

The answer to all these questions is a resounding NO. Few funders are eager to support scientific studies of drug abuse, poverty, nonstandard families, or technology, partly because people have strong opinions and economic motives that may conflict with scientific findings and conclusions.

The next cohort of developmental scientists will build on what is known, mindful of what needs to be explored, answering the questions just posed and many more. Remember that the goal is to help all 7 billion people on Earth fulfill their potential. Much more needs to be learned. The rest of this book is a start.

SUMMING UP Although science has improved human development in many ways, caution is needed in interpreting results and in designing research. Sometimes people think that correlation indicates cause. It does not.

Research on human development must subscribe to high ethical standards. Participants must be respected and must give informed consent. Political and publishing concerns can interfere with objective research. Scientists must study and report data on issues that affect the development of all people.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 1.26

Why does correlation not prove causation?

A correlation looks at the relationship between two variables, such as age and height. As children age, they generally get taller. However, correlation is not causation. Just because two variables are correlated does not mean that one causes the other. Correlation proves only that the variables may be connected.Question 1.27

Why do most colleges and hospitals have an IRB?

An Institutional Review Board (IRB) is a group that permits only research that follows certain ethical guidelines. Some research conducted in the past was unethical, especially when the participants were children, members of minority groups, prisoners, or animals.Question 1.28

What are the primary ethical principles used when scientists study humans?

The most important safeguards are those that ensure no one is harmed by the study. Participation must be voluntary and confidential. This entails informed consent of the participants—that is, they must understand and agree to the research procedures, knowing that risks are involved. For children, consent must be obtained from parents as well, and the children must be allowed to end their participation at any time. When the study is over, participants must also be debriefed— told what the study was about and what the results were. Question 1.29

Why are some important questions about human development not yet answered?

Do we know enough about prenatal drug abuse to protect every fetus?

Do we know enough about poverty to enable everyone to be healthy?

Do we know enough about various family structures to understand the impact on children of marriage, or divorce, or single parenthood?

Do we know enough about television, video games, the Internet, and cell phones to use these to enhance learning and not harm children?