Cognitive Theory: Piaget and Information Processing

Social scientists sometimes write about the “cognitive revolution,” which occurred in about 1980 when psychoanalytic and behaviorist research and therapy were overtaken by a focus on cognition. That does not mean that behaviorism and psychoanalysis are no longer relevant: The cognitive revolution adds another aspect to our understanding of children without demolishing previous conceptions of development (Watrin & Darwich, 2012).

According to cognitive theory, thoughts and expectations profoundly affect attitudes, beliefs, values, assumptions, and actions. This revolution was the result of an increasing awareness of the power of the mind. Cognitive theory dominated psychology for decades, becoming a grand theory.

Piaget’s Stages of Development

The first major cognitive theorist was the Swiss scientist Jean Piaget (1896–

Although he did his job, noting when children knew, for example, that a bicycle had two wheels and a hand had five fingers, it was the children’s wrong answers that intrigued him. How children think is much more revealing, Piaget concluded, than what they know.

In the 1920s, most scientists believed that babies could not yet think. But Piaget used scientific observation with his own three infants, finding them curious and thoughtful.

Later he studied hundreds of schoolchildren. From this work, Piaget formed the central thesis of cognitive theory: How children think changes with time and experience, and their thought processes affect their behavior. According to cognitive theory, to understand humans of any age, one must understand intellectual processes.

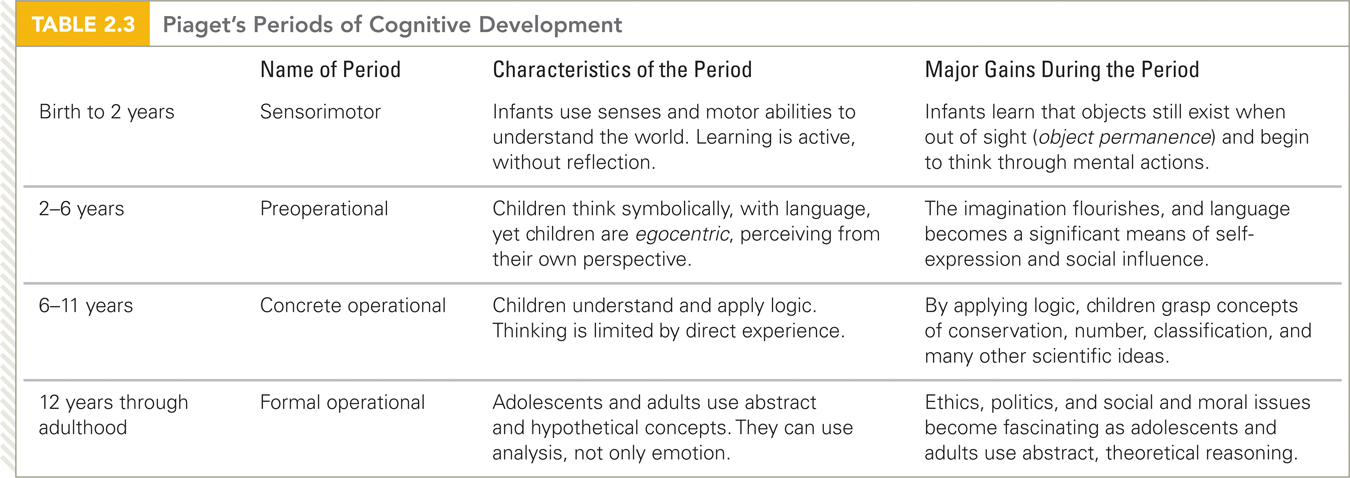

Piaget maintained that cognitive development occurs in four age-

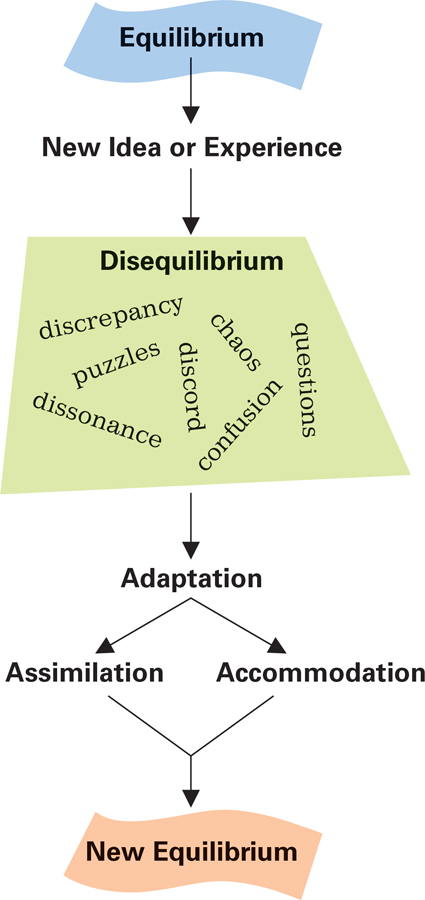

Piaget found that intellectual advancement occurs because humans at every age seek cognitive equilibrium—a state of mental balance. The easiest way to achieve this balance is to interpret new experiences through the lens of preexisting ideas. For example, infants grab new objects in the same way that they grasp familiar objects, a child’s first concept of God is as a loving—

Achieving equilibrium is not always easy, however. Sometimes a new experience or question is jarring or incomprehensible. Then the individual experiences cognitive disequilibrium, an imbalance that creates confusion. As Figure 2.1 illustrates, disequilibrium can cause cognitive growth if people adapt their thinking. Piaget describes two types of cognitive adaptation:

Assimilation: New experiences are reinterpreted to fit, or assimilate, into old ideas.

Accommodation: Old ideas are restructured to include, or accommodate, new experiences.

Challenge Me Most of us, most of the time, prefer the comfort of our conventional conclusions. According to Piaget, however, when new ideas disturb our thinking, we have an opportunity to expand our cognition with a broader and deeper understanding. Living in another country, attending college far from home, or even a deep conversation with someone who disagrees with you—

Accommodation is more difficult than assimilation, but it advances thought. Children—

Ideally, when two people disagree, or when they surprise each other by what they say, adaptation is mutual. For example, when parents are startled by their children’s opinions, the parents may revise their concepts of their children and even of reality, accommodating to new perceptions. If an honest discussion occurs, the children, too, might accommodate. Cognitive growth is an active process; clashing concepts require new thought.

Information Processing

Piaget is credited with discovering that people’s assumptions and perceptions affect their development, an idea now accepted by most social scientists. However, many think Piaget’s theories were limited. Neuroscience, cross-

As one admirer explains, Piaget’s “claims were too narrow and too broad” (Hopkins, 2011, p. 35). The narrowness comes from his focus on science, ignoring that people can be advanced in their understanding of physics and biology but not in other aspects of thought. The broadness is in his description of stages. Contrary to Piaget’s ideas, “intelligence is now viewed more as a modular system than as a unified system of general intelligence” (Hopkins, 2011, p. 35).

Now consider a newer version of cognitive theory, information-

Information processing is “a framework characterizing a large number of research programs” (Miller, 2011, p. 266). Instead of interpreting responses by infants and children, as Piaget did, this cognitive theory focuses on the processes of thought—

Information-

According to this perspective, cognition begins when input is picked up by the five senses. It proceeds to brain reactions, connections, and stored memories, and it concludes with some form of output. For infants, output consists of moving a hand, making a sound, or staring a split second longer at one stimulus than at another. As a person develops, information-

The latest techniques to study the brain have produced insights from neuroscience on the sequence and strength of neuronal communication and have discovered patterns beyond those traced by early information-

However, the basic tenet of cognitive theory is true for neuroscience, information processing, and for Piaget: Ideas matter. For example, how children interpret a future social situation, such as whether they anticipate welcome or rejection, affects the quality of their actual friendships. Positive information processing correlates with positive friendships.

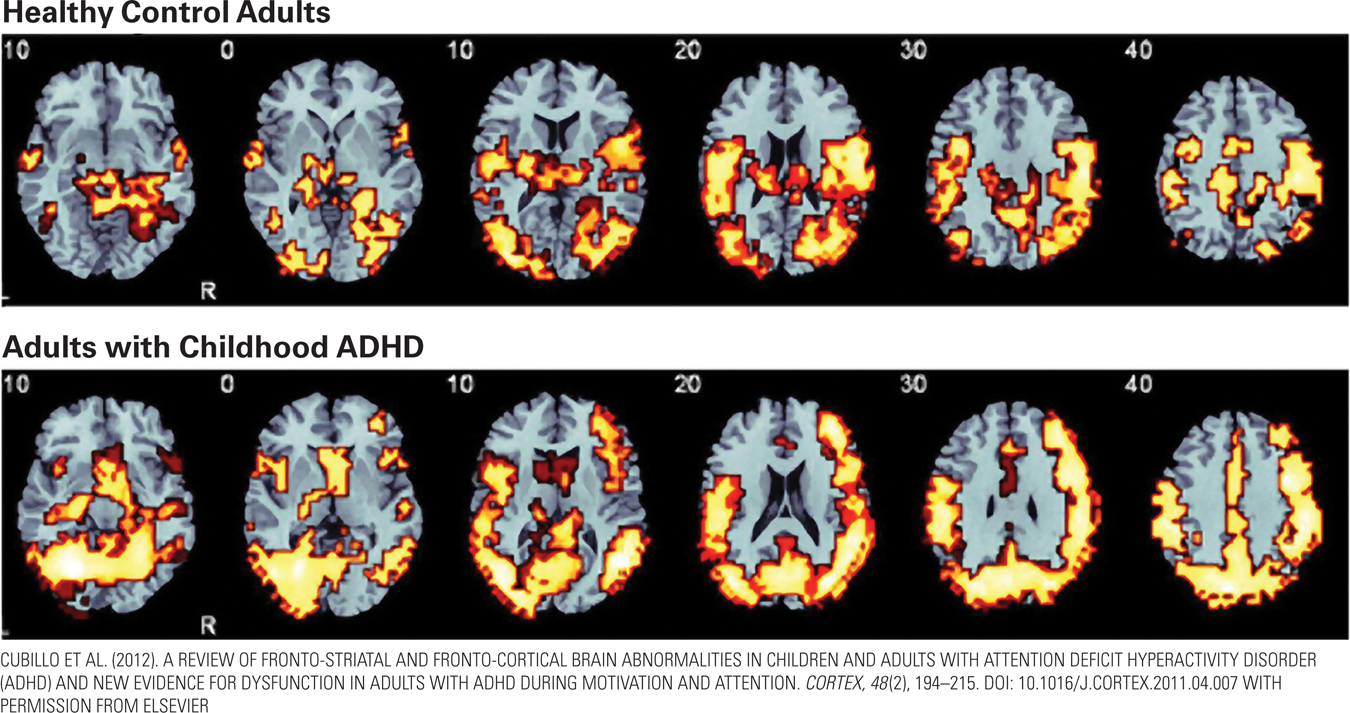

This approach to understanding cognition has many applications. For instance, it has long been recognized that children with ADHD (attention-

This means that children with ADHD may not know whether their father’s “Come here” is an angry command or a loving suggestion. Nor do they immediately know if a classmate is hostile or friendly. Information processing helps in remediation: If a specific brain function can be improved, children may learn more, obey more, and gain friends.

Remember that all theories are designed to be useful. The Opposing Perspectives feature is one illustration of the way psychoanalytic, behaviorist, and cognitive theory might apply to common parental concerns—

opposing perspectives

Toilet Training—

Parents hear opposite advice about when to respond to an infant’s cry. Some experts tell them that ignoring the cry will reduce the infant’s future happiness (psychoanalytic theory—

Meanwhile, cognitive theory seeks to understand the reason for the cry. Is it a reflexive wail of hurt and hunger, or is it an expression of social pain? According to this theory, when people understand what a particular action means to the actor, then effective response is possible. Thus all three theories have led to advice for parents—

Another practical example is toilet training. In the nineteenth century, many parents believed that bodily functions should be controlled as soon as possible in order to distinguish humans from lower animals. Consequently, they began toilet training in the first months of life (Accardo, 2006). Then psychoanalytic theory pegged the first year as the oral stage (Freud) or the time when trust was crucial (Erikson), before the toddler’s anal stage (Freud) began or autonomy needs (Erikson) emerged.

Consequently, psychoanalytic theory led to postponing toilet training to avoid serious personality problems later on. Soon this was part of many manuals on child rearing. For example, a leading pediatrician, Barry Brazelton, wrote a popular book for parents advising that toilet training should not begin until the child is cognitively, emotionally, and biologically ready—

As a society, we are far too concerned about pushing children to be toilet trained early. I don’t even like the phrase “toilet training.” It really should be toilet learning.

[Brazelton & Sparrow, 2006, p. 193]

By the middle of the twentieth century, many U.S. psychologists had rejected psychoanalytic theory and become behaviorists. Since they believed that learning depends primarily on conditioning, some suggested that toilet training occur whenever the parent wished, not at a particular age. In one application of behaviorism, children drank quantities of their favorite juice, sat on the potty with a parent nearby to keep them entertained, and then, when the inevitable occurred, the parent praised and rewarded them—

Rejecting both of these theories, some Western parents prefer to start potty training very early. One U.S. mother began training her baby just 33 days after birth. She noticed when her son was about to defecate, held him above the toilet, and had trained him by 6 months (Sun & Rugolotto, 2004). Such early training is criticized by all of the grand theories, although each theory has a particular critique, as now explained.

Psychoanalysts would wonder what made her such an anal person, with a need for cleanliness and order that did not consider the child’s needs. Behaviorists would say that the mother was trained, not the son. She taught herself to be sensitive to his body; she was reinforced when she read his clues correctly. Cognitive theory would wonder what the mother was thinking. For instance, did she have an odd fear of normal body functions?

What is best? Dueling theories and diverse parental practices have led the authors of an article for pediatricians to conclude that “despite families and physicians having addressed this issue for generations, there still is no consensus regarding the best method or even a standard definition of toilet training” (Howell et al., 2010, p. 262). One comparison study of toilet-

That conclusion arises from cognitive theory, which holds that each person’s assumptions and ideas determine their actions. Therefore, since North American parents are from many cultures with diverse assumptions, marked variation is evident in beliefs regarding toilet training.

Contemporary child-

What values are embedded in each practice? Psychoanalytic theory focuses on later personality, behaviorism stresses conditioning of body impulses, and cognitive theory considers variation in the child’s intellectual capacity and in adult values. Even the idea that each child is different, making no one method best, is the outgrowth of a theory. There is no easy answer, but many parents are firm believers in one approach or another. That confirms the statement at the beginning of this chapter: We all have theories, sometimes strongly held, whether we know it or not.

SUMMING UP Cognitive theory holds that to understand a person, one must learn how that person thinks. According to Piaget, cognition develops in four distinct, age-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 2.12

What is the basic idea of cognitive theory?

According to cognitive theory, our thoughts shape our attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.Question 2.13

How do the processes of assimilation and accommodation lead to more advanced thinking?

Assimilation allows us to reinterpret new experiences to fit into old ideas. Accommodation is the restructuring of old ideas to include new experiences. Accommodation is more difficult than assimilation, but it advances thought. According to Piaget, children construct ideas based on their experiences.Question 2.14

In what ways are assimilation and accommodation similar?

Assimilation is the process by which new ideas or experiences are interpreted in a way that fits with prior knowledge, and accommodation is modifying prior knowledge based on new experiences. Both processes are similar in that they are used to ease the cognitive disequilibrium created by new experiences.Question 2.15

How does information processing connect to neuroscience, the study of the brain?

Recent techniques to study the brain have produced insights from neuroscience on the sequence and strength of neuronal communication and have discovered patterns beyond those traced by early information–processing theory. With the aid of sensitive technology, information– processing research has also overturned some of Piaget's findings. Question 2.16

What do all the cognitive theories have in common?

All cognitive theories recognize that thoughts and expectations profoundly affect attitudes, beliefs, values, assumptions, and actions.