Sociocultural Theory: Vygotsky and Beyond

New theories have emerged that are multicultural and multidisciplinary, unlike the first three theories. These theories are “new” in that their applications to human development are relatively recent, although their roots are ancient.

The central thesis of sociocultural theory is that human development results from the dynamic interaction between developing persons and their surrounding society. Culture is viewed not as something external that impinges on developing persons but as integral to their development every day via the social context (all the dynamic systems described in Chapter 1).

Social Interaction

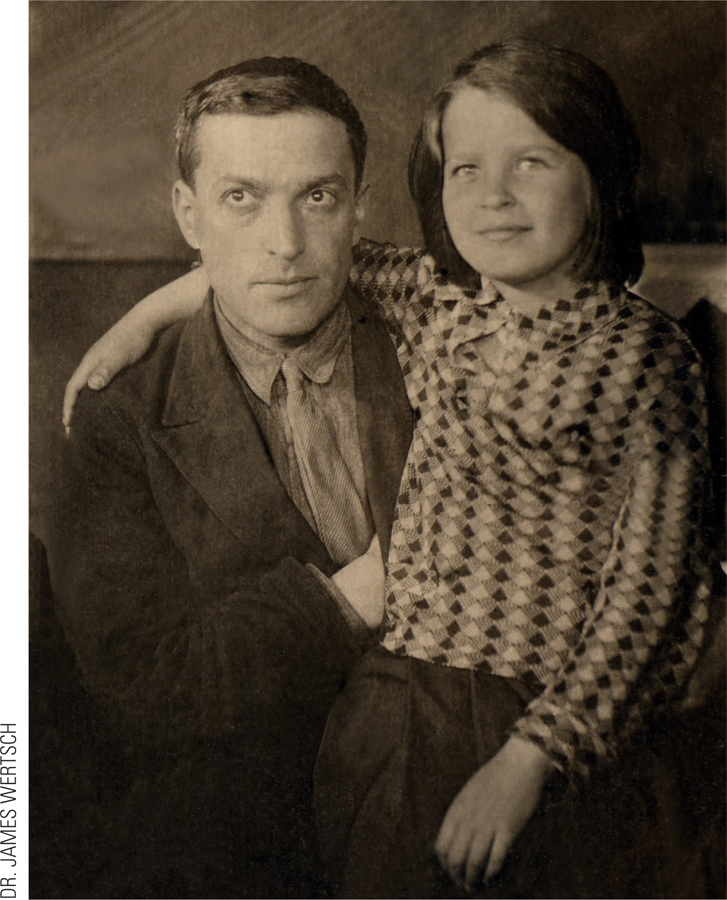

The pioneer of the sociocultural perspective was Lev Vygotsky (1896–

Vygotsky noted that each community in his native land (comprising Asians and Europeans of many faiths and many languages) taught children whatever beliefs and habits they valued. For example, his research included how farmers used tools, how illiterate people thought of abstract ideas, and how children learned in school.

In his view, each person, schooled or not, develops with the guidance of more skilled members of his or her society, who are tutors or mentors in an apprenticeship in thinking (Vygotsky, 2012). Just as, in earlier centuries, a young person might become an apprentice to an experienced artisan, learning the trade, Vygotsky believed that adults teach children how to think by explaining ideas, asking questions, and repeating values.

To describe this process, Vygotsky developed the concept of guided participation, the method used by parents, teachers, and entire societies to teach novices the skills and habits expected within their culture. Tutors engage learners (also called apprentices) in joint activities, offering instruction and “mutual involvement in several widespread cultural practices with great importance for learning: narratives, routines, and play” (Rogoff, 2003, p. 285). Active apprenticeship and sensitive guidance are central to sociocultural theory because each person depends on others to learn. This process is informal, pervasive, and social.

All cultural patterns and beliefs are social constructions, not natural laws, according to sociocultural theorists. These theorists find customs to be powerful, shaping the development of every person, and they contend that some assumptions need to shift to allow healthier development. Vygotsky stressed this point, arguing that disabled children should be educated (Vygotsky, 1994b). This is a cultural belief that has become law in the United States but is not yet accepted in many other nations.

The Zone of Proximal Development

According to sociocultural theory, all learning is social, whether people are learning a manual skill, a social custom, or a language. As part of the apprenticeship of thinking, a mentor (parent, peer, or professional) finds the learner’s zone of proximal development, an imaginary area surrounding the child, which contains the skills, knowledge, and concepts that the learner is close (proximal) to acquiring but cannot yet master without help.

The Magic Middle Somewhere between the boring and the impossible is the zone of proximal development, where interaction between teacher and learner results in knowledge never before grasped or skills not already mastered. The intellectual excitement of that zone is the origin of the joy that both instruction and study can bring.

Through sensitive assessment of each learner, mentors engage mentees within that zone. Together, in a “process of joint construction,” new knowledge is attained (Valsiner, 2006). The mentor must avoid two opposite dangers: boredom and failure. Some frustration is permitted, but the learner must be actively engaged, never passive or overwhelmed (see Figure 2.2).

To make this seemingly abstract process more concrete, consider an example: a father teaching his daughter to ride a bicycle. He begins by rolling her along, supporting her weight while telling her to keep her hands on the handlebars, to push the right and left pedals in rhythm, and to look straight ahead. As she becomes more comfortable and confident, he begins to roll her along more quickly, praising her for steadily pumping. Within a few lessons, he is jogging beside her, holding only the handlebars.

When the father senses that his daughter can balance, he urges her to pedal faster while he loosens his grip. Without realizing it, she rides on her own.

Note that this is not instruction by preset rules or reinforcement. Sociocultural learning is active: No one learns to ride a bike by reading and memorizing written instructions, and no good teacher merely repeats a prepared lesson. Also note that the father is not the only teacher here. The culture also teaches, via the child having seen other people on bikes, and via special bikes for young children. All such bikes are smaller, of course, but some have no pedals and some have training wheels, both of which are cultural artifacts that can help guide participation in bike riding.

Because each learner has personal traits and experiences, education must be individualized. Learning styles vary: Some people need more assurance; some learn best by looking, others by hearing.

A mentor must sense when support or freedom is needed and how peers can help (they may be the best mentors). Skilled teachers know when the zone of proximal development expands and shifts.

Excursions into and through the zone of proximal development are everywhere. At the thousand or so science museums in the United States, children ask numerous questions, and adults guide their scientific knowledge (Haden, 2010). Physical therapists tailor exercises to the particular patient and the surrounding context. For example, when physical therapists provide exercise for patients in intensive care, they not only take into account the illness but also the culture of the ICU (Pawlik & Kress, 2013).

In another example that occurs for every Western child, learning to sit at the table and eat with a knife and fork is a long process, with many steps of guided participation. Parents do not “spoon-

In general, mentors, attuned to ever-

Taking Culture into Account

The sociocultural perspective has led contemporary scientists to consider social context in every study. Earlier theorists and researchers are criticized for failing to do so. This newer approach considers not only differences between one nation and another, but also differences between one region and another, between one cohort and another, between one ethnic group and another, and so on.

This approach has led to a wealth of provocative findings, many of which are described later. A sociocultural perspective has been particularly helpful in early childhood education (Woodrow, 2014), as children have diverse cultural experiences by the time they enter preschool.

Culture is not a monolith, with every child in a particular community, or even a particular family, experiencing the same influences. Instead, culture needs to be considered person by person: Each individual participates in some aspects of the community culture while rejecting or modifying others.

Consider two sisters:

When the local constables knocked on Chona’s parents’ door with their wooden staffs, searching for children to send to the school, her parents hid their children under the wooden bed just inside the door and told the constables that the children did not exist. But Chona’s sister Susana, ever rebellious, leaped out from under the bed and yelled … “I want to go to school.”

[Rogoff, 2011, p. 5]

Especially for Adoptive Families Does the importance of attachment mean that adopted children will not bond securely with nonbiological caregivers?

Not at all. Attachment is the result of responsiveness, not biology. In some cultures, many children are adopted from infancy, and the emotional ties to their caregivers are no less strong than for other children.

These two sisters, both speaking a local language, raised in the same tribal culture (Mayan, in San Pedro, Guatemala), nevertheless followed distinct cultural paths. Later Susana refused an arranged marriage and moved to a nearby town, unlike her unschooled sister who married a man she did not like and stayed close to her childhood home all her life. Culture shapes everyone, but each person experiences it differently.

SUMMING UP Sociocultural theory is more multicultural than the theories described earlier in this chapter. The pioneer of sociocultural theory was Lev Vygotsky, who said that each learner is an apprentice, guided by a more skilled or knowledgeable person. Learning occurs within a zone a proximal development, that region that the learner is almost able to learn—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 2.17

How is “apprenticeship in thinking” an example of sociocultural theory?

Vygotsky's work focuses on the relationship between education and culture. His “apprenticeship in thinking” refers to the idea that children and adults develop with the help, or apprenticeship, of more skilled members of society after whom they model themselves.Question 2.18

How does the teacher encourage learning in the zone of proximal development?

Through sensitive assessment of each learner, the teacher engages the student within that zone. Together, in a process of joint construction, new knowledge is attained. The teacher must avoid two opposite dangers: boredom and failure. Some frustration is permitted, but the learner must be actively engaged, never passive or overwhelmed.Question 2.19

What is an example of a cultural difference in the expectations a child might have about school?

A child from a middle–class, Western nation is likely to value education and perceive it as important to the fulfillment of long– term goals. A child from a tribal culture, in contrast, may focus more on learning a trade through careful observation of adults. He may place much less value on formal education than the first child described.