The Universal Perspective: Humanism and Evolution

No developmentalist doubts that each person is unique, yet many social scientists contend that the sociocultural focus on differences (cultural, ethnic, sexual, economic) depicts a fractured understanding of development.

Moreover, no developmentalist doubts that nonhuman animals can help us understand humans. However, many think that the psychoanalytic emphasis on sexual needs, and the behaviorist stress on laws of behavior, ignore aspects of development that characterize all humans but not all animals.

Universal theories hold that people share impulses and motivations, which they express in ways most other animals cannot. A universal perspective has been articulated in many developmental theories, each expressed in particular ways but always contending that humans have much in common with each other.

Here we describe two of the most prominent of such perspectives: humanism and evolutionary theory. These two may seem to be opposite, in that humanism emphasizes the heights of human striving and evolutionary theory begins with consideration of quite simple instincts, but several recent scholars have found many similarities in these theories, contending that the “hierarchy of human motives” (humanism) can be anchored “firmly in the bedrock of modern evolutionary theory” (Kenrick et al., 2010, p. 292).

Humanism

Many scientists are convinced that there is something hopeful, unifying, and noble in the human spirit, something ignored by psychoanalytic theory (which envisions self-

Maslow and Rogers had witnessed the Great Depression and two world wars and concluded that traditional psychological theories underrated human potential by focusing on evil, not good. They founded a theory called humanism that became prominent after World War II, as millions read Maslow’s Toward a Psychology of Being (1999) and Rogers’s On Becoming a Person (2004).

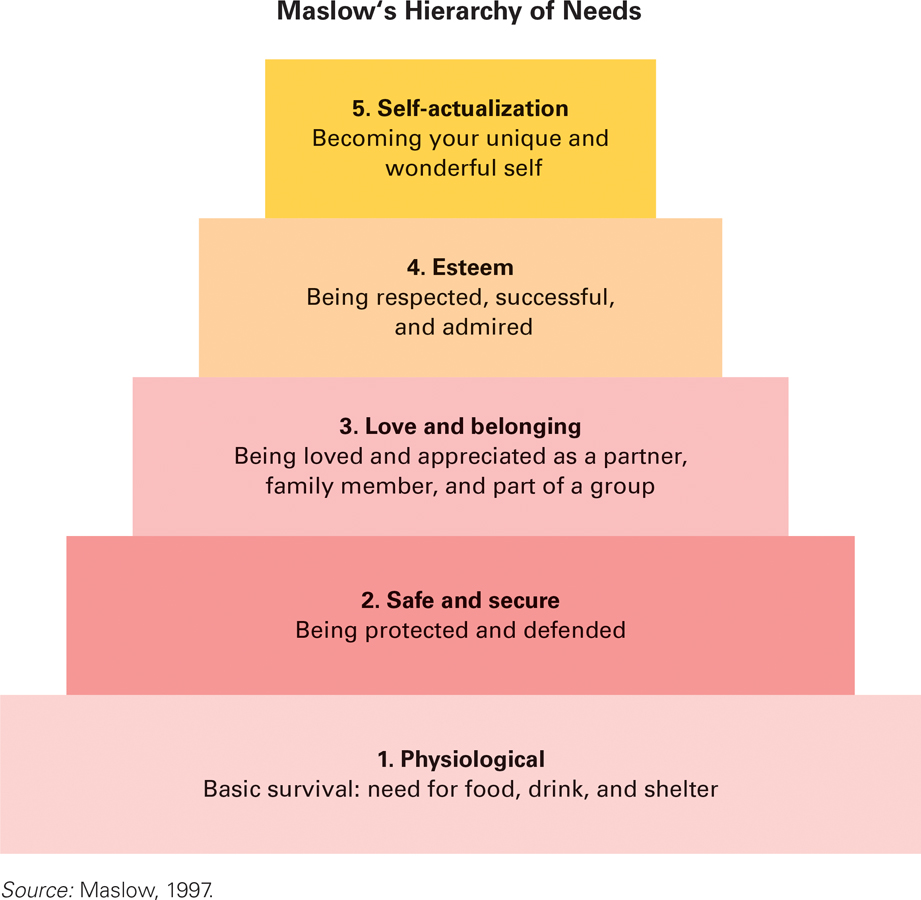

Maslow believed that all people—

Moving Up, Not Looking Back Maslow’s hierarchy is like a ladder: Once a person stands firmly on a higher rung, the lower rungs are no longer needed. Thus, someone who has arrived at step 4 might devalue safety (step 2) and risk personal safety to gain respect.

Physiological: needing food, water, warmth, and air

Safety: feeling protected from injury and death

Love and belonging: having friends, family, and a community (often religious)

Esteem: being respected by the wider community as well as by oneself

Self-

actualization: becoming truly oneself, fulfilling one’s unique potential while appreciating all of humanity

This pyramid caught on almost immediately; it was one of the most “contagious ideas of behavioral science” because it seemed insightful about human psychology (Kenrick et al., 2010, p. 292). This theory is not a developmental theory in the traditional sense, in that Maslow did not believe that the levels were connected to a particular stage or age. However, his levels are sequential: Lower levels need to be satisfied before the higher levels.

Thus meeting a child’s needs for basic care, for safety, and for friendship was a prerequisite for self-

Rogers also stressed the need to accept and respect one’s own personhood as well as that of everyone else. He thought that people should give each other unconditional positive regard, which means that they should see (regard) each other with appreciation (positive) without conditions (unconditional). This is what parents often do for their children: they love and cherish them even when the child cries, disobeys, or encounters trouble.

If parents do not have unconditional positive regard for their children, the danger is that the children will have long-

As you can see, humanists emphasize what all people have in common, not their national, ethnic, or cultural divisions. Maslow contended that everyone, universally, must satisfy each lower level of the hierarchy of needs before moving higher. A starving man, for instance, may not be concerned for his own safety when he seeks food (level 1 precedes level 2), or an unloved woman might not care about self-

Maslow thus was more accepting of people who others see as hostile to their nation, or religion, or group. Destructive and inhumane actions may be the consequence of unmet lower needs, which may be met later if a child was neglected or abused. Recovery is possible.

Notice the relevance for child development. Babies seek food and comfort, children seek approval, and not until adulthood can a person focus wholeheartedly on success and esteem, beyond the immediate approval of friends and family. Satisfaction of early needs is crucial for later self-

Rogers agreed that adults who were deprived of unconditional positive regard in childhood might become selfish and antisocial. He developed a method of psychological therapy widely used to help people become more accepting of themselves and therefore of other people, overcoming early deprivation.

Especially for Nurses Maslow’s hierarchy is often taught in health sciences because it alerts medical staff to the needs of patients. What specific hospital procedures might help?

Reassurance from nurses (explaining procedures, including specifics and reasons) helps with the first two, and visitors, cards, and calls might help with the next two. Obviously, specifics depend on the patient, but everyone needs respect as well as physical care.

Humanism is still prominent among medical professionals because they recognize that pain is not always physical (the first two levels) but can also be social (the next two) (Majercsik, 2005; Zalenski & Raspa, 2006). Even the very sick need love and belonging (friends and family) and esteem (the dying need respect).

Evolutionary Theory

You are familiar with Charles Darwin and his ideas, first published 150 years ago: Essentially he showed that plants, insects, birds, and animals developed over billions of years, as life evolved from primitive cells to humans (Darwin, 1859).

But you may not realize that serious research on human development inspired by this theory does not focus on lower creatures, but instead studies the history of human characteristics. Evolutionary psychology is quite recent (Simpson & Kenrick, 2013). As two leaders in this field write:

During the last two decades, the study of the evolutionary foundations of human nature has grown at an exponential rate. In fact, it is now a booming interdisciplinary scientific enterprise, one that sits at the cutting edge of the social and behavioral sciences.

[Gangestad & Simpson, 2007, p. 2]

Why Adults Protect Their Children

Evolutionary theory has intriguing explanations for many issues in human development, including a pregnant woman’s nausea, 1-

To understand human development, this theory contends that humans should understand the lives of our early ancestors. For example, many people are terrified of snakes; they scream and break into a cold sweat upon seeing one. However, virtually no one is terrified of automobiles. Yet for current deaths in the United States, the ratio of snake to car deaths is 1 to 10,000. In 2014, only two people died from snake bites: a Kentucky man in a snake-

evolutionarily, ancient dangers such as snakes, spiders, heights, and strangers appear on lists of common phobias far more often than do evolutionarily modern dangers such as cars and guns, even though cars and guns are more dangerous to survival in the modern environment.

[Confer et al., 2010, p. 111]

Since our fears have not caught up to modern inventions, we use our minds to pass laws regarding infant seats, child safety restraints, seat belts, red lights, and speed limits. Humanity is succeeding in such measures: The U.S. motor-

Especially for Teachers and Counselors of Teenagers Teen pregnancy is destructive of adolescent education, family life, and sometimes even health. According to evolutionary theory, what can be done about this?

Evolutionary theory stresses the basic human drive for reproduction, which gives teenagers a powerful sex drive. Thus, merely informing teenagers of the difficulty of caring for a newborn (some high school sex-

Other modern killers—

According to evolutionary theory, every species has two long-

Later chapters will explain these, but here is one example. Adults consider babies cute—

A competing instinct is to perpetuate one’s progeny, even at the expense of other people’s children. That might lead to infanticide, again explained by evolutionary theory. Chimpanzee males who take over a troop kill babies of the deposed male; humans, of course, have created laws against such practices (Hrdy, 2009).

Genetic Links

A basic idea from evolutionary theory—

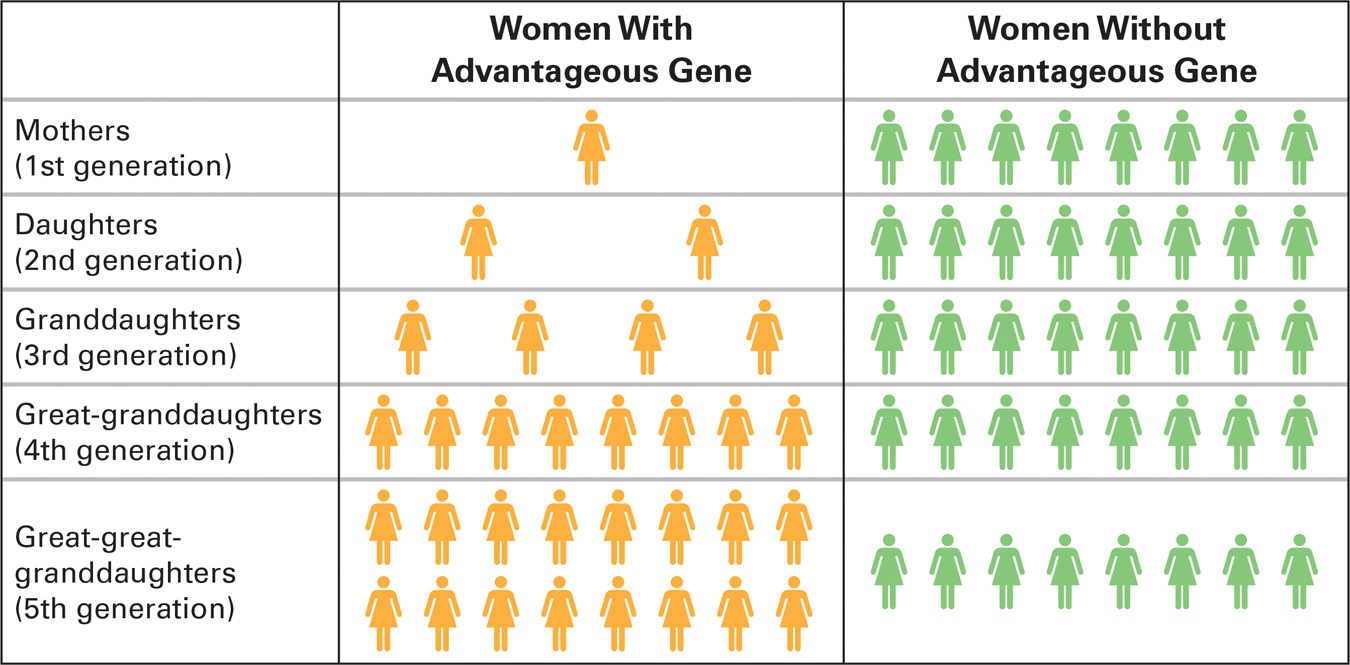

Selective Adaptation Illustrated Suppose only one of nine mothers happened to have a gene that improved survival. The average woman had only one surviving daughter but this gene mutation might mean more births and more surviving children, such that each woman who had the gene bore two girls who survived to womanhood instead of one. As you see, in 100 years, the “odd” gene becomes more common, making it a new normal.

Some of the best qualities of people—

The process of selective adaptation works as follows: If one person happens to have a trait that makes survival more likely, the gene (or combination of genes) responsible for that trait is likely to be passed on to the next generation because that person is likely to survive long enough to reproduce. Anyone who inherits a beneficial gene (or combination of genes) has an increased chance of growing up, finding a mate, and bearing children—

For example, originally almost all human babies could digest lactose in their mother’s milk but probably became lactose intolerant as they grew older, and therefore unable to digest too much cow’s milk (Suchy et al., 2010). In a few regions thousands of years ago cattle were domesticated and raised for their meat. In those places, “killing the fatted calf” provided a rare feast for the entire community when a major celebration occurred.

In cattle-

This process of selective adaptation continues over many generations. The fact that the odd gene for lactose tolerance became more common, providing survival in cattle-

Once it was understood that milk might make some children sick, better ways to relieve hunger were found. Although malnutrition is still a global problem, about a third fewer children are malnourished than was the case in 1990 (UNICEF, 2012). One reason is that nutritionists now know which foods are digestible, nourishing, and tasty for whom. Evolutionary psychology has helped with that.

For groups as well as individuals, evolutionary theory notices how the interaction of genes and environment affects survival and reproduction. Genetic variations are particularly beneficial when the environment changes, which is one reason genetic diversity benefits humanity as a whole.

If a species’ gene pool does not include variants that allow survival in difficult circumstances (such as exposure to a new disease or to an environmental toxin), the entire species becomes extinct. One recent example is HIV/AIDS, deadly in most untreated people but not in a few who are genetically spared. No wonder biologists worry when a particular species becomes inbred—

Evolution and Culture

Genetic variation among humans, differential sensitivity, and plasticity (explained in Chapter 1) enable humans to survive and multiply. This variation applies not only to biological traits (such as digestion of milk) but also to psychological traits that originate in the brain and then are shaped by culture (Confer et al., 2010; Tomasello, 2009).

Evolutionary theory contends that certain epigenetic factors foster socialization, parenthood, communication, and language, all of which helped humans a hundred thousand years ago and allowed societies a few thousand years ago to develop writing, then books, and then universities. As a result, humans learn from history and from strangers in distant continents. The fact that you are reading this book, accepting some ideas and rejecting others, is part of the human heritage that will aid future generations, according to evolutionary theory.

In recent years, “evolutionary psychology has grown from being viewed as a fringe theoretical perspective to occupying a central place within psychological science” (Confer et al., 2010). This theory is insightful and intriguing, but some interpretations are hotly disputed.

For instance, an evolutionary account of mental disorders suggests that some symptoms (such as an overactive imagination or crushing anxiety) are normal extremes of adaptive traits, and that few people should be considered mentally ill. In this view, depression particularly can be seen to have been adaptive in ancient times, and now is seen as a mood that needs to be treated with respect and by making changes in life circumstances rather than treating it with drugs (Rothenberg, 2014).

This perspective is rejected by many psychologists and by neuroscientists who consider many forms of mental illness to be caused by an imbalance of neurotransmitters or a deficit in some particular parts of the brain. Also controversial are explanations of sex differences, as the following explains.

a view from science

If Your Mate Were Unfaithful

Men seek more sexual partners than women do. Brides are younger, on average, than grooms. These are norms, not followed in every case, but apparent in every culture. Why?

An evolutionary explanation begins with biology. Since females, not males, become pregnant and breast-

A man was more able to father many children if he removed his rivals and had multiple sexual partners—

The evolutionary reasons for men to become faithful partners to one woman despite their impulse included the fact that men needed to keep other men away in order to protect their children (Lukas & Clutton-

Does this interpretation have empirical research support? Evolutionary scientists have asked people of many ages, nationalities, and religions to imagine their romantic partner either “forming a deep emotional attachment” or “enjoying passionate sexual intercourse” with another man or woman. Then the participants are asked which of those two possibilities is more distressing. The men generally are more upset at sexual infidelity while the women are more upset with emotional infidelity (Buss et al., 2001).

For example, one study involved 212 college students, all U.S. citizens, whose parents were born in Mexico (Cramer et al., 2009). As with other populations, more women (60 percent) were distressed at the emotional infidelity and more men (66 percent) at the sexual infidelity.

A meta-

Evolutionary theory explains this oft-

Many women reject the evolutionary explanation for sex differences. They contend that hypothetical scenarios do not reflect actual experience and that patriarchy and sexism, not genes, produce mating attitudes and patterns (Vandermassen, 2005; Varga et al., 2011).

Similar controversies arise with other applications of evolutionary theory. People do not always act as evolutionary theory predicts: Parents sometimes abandon their newborns, adults sometimes handle snakes, and so on. In the survey of Mexican American college students that was cited in A View from Science, more than one-

Nonetheless, evolutionary theorists contend that humans need to understand the universal, biological impulses within our species in order to control destructive reactions (e.g., we need to make “crimes of passion” illegal) and to promote constructive ones (to protect against newer dangers by manufacturing safer cars and guns).

SUMMING UP Universal theories include humanism and evolutionary theory, both of which stress that all people have the same underlying needs. Humanism holds that everyone merits respect and positive regard in order to become self-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 2.20

Why is humanism considered a hopeful theory?

Many scientists are convinced that there is something hopeful, unifying, and noble in the human spirit, something ignored by psychoanalytic theory and behaviorism. Humanism stresses free will and self–determination. It emphasizes that people are good and want to do what is right. Question 2.21

How does Maslow’s hierarchy of needs differ from Erikson’s stages?

Maslow's hierarchy is not age–specific and doesn't involve any specific task to achieve. It simply states basic human needs required for all ages and postulates that having unmet needs prevents a person from progressing any further in the hierarchy, thus limiting his or her capabilities and contributions to society. Question 2.22

How does evolutionary psychology explain human instincts?

Evolutionary theory states that human instincts are based on selective adaptation, which proposes that humans today react in ways that helped their survival and reproduction long ago. This may be why people fear snakes and spiders. It also explains why someone spits out something that is spoiled or bitter.Question 2.23

What is the evolutionary explanation of why parents protect their children?

According to evolutionary theory, every species has two long–standing, biologically– based drives: survival and reproduction. In order to maintain the survival of our species, parents must look out for the health and well– being of their offspring. Question 2.24

What does the idea of selective adaptation imply about genetics?

It implies that nature (genetics) is more important than nurture since traits and behaviors that have benefitted the species' survival have been preserved over the generations.Question 2.25

Why do many women disagree with the evolutionary explanation of sex differences?

Many women disagree with the evolutionary perspective because they contend that hypothetical scenarios do not reflect actual experience and that patriarchy and sexism, not genes, produce mating attitudes and patterns.