Chromosomal and Genetic Problems

Video: Genetic DisordersMONKEY BUSINESS IMAGES/SHUTTERSTOCK

We now focus on conditions caused by an extra chromosome or a single destructive gene. Three factors make these conditions relevant to human development:

They provide insight into the complexities of nature and nurture.

Knowing their origins helps limit their effects.

Information combats prejudice: Difference is not always deficit.

Not Exactly 46

As you know, each sperm or ovum usually has 23 chromosomes, creating a zygote with 46 chromosomes and eventually a person. However, cells do not always split exactly in half to make those reproductive cells.

One variable known to correlate with chromosomal abnormalities is the parents’ age, particularly the age of the mother. A suggested explanation is that, since ova begin to form before a girl is born, older mothers have older ova. When the 46 chromosomes of the mother make ova, usually the split is even, 23/23. But older women are more likely to have some ova that have 22 or 24 chromosomes. Sperm also are diminished in quantity and normality as men age.

Miscounts are not rare. One estimate is that 5 to 10 percent of all zygotes have more or fewer than 46 chromosomes (Brooker, 2009); another estimate suggests that the rate is as high as 50 percent (Fragouli & Wells, 2011). Estimates vary because no one knows for certain. Almost all abnormal zygotes fail to duplicate, divide, differentiate, and implant, or are spontaneously aborted before a woman even knows she is pregnant. Thus an accurate count of zygotes with extra chromosomes is impossible to obtain.

If implantation does occur, many zygotes with chromosomal miscounts are aborted, either spontaneously (miscarried) or by choice. It is estimated that the abortion rate for such zygotes is about 5 percent. Ninety-

About 5 percent of stillborn (dead at birth) babies have 47 chromosomes (Miller & Therman, 2001), and many other babies with 47 chromosomes die within the first few days. Only once in about every 200 births does a newborn survive with 45, 47, or, rarely, 48 or 49 chromosomes.

Survival is much more common if some of the cells have 46 chromosomes and some 47, a condition called mosaicism, or if the problem does not involve a whole chromosome but only a missing or extra piece of a chromosome. Overall, advanced analysis suggests mosaicism “may represent the rule rather than the exception” (Lupski, 2013, p. 358). We may all be mosaics, some more than others. Usually this has no detectable effect on development, although it seems as if cancer is more likely if a person has extra or missing genetic material.

Down Syndrome

If an entire chromosome is missing or added, that leads to a recognizable syndrome, a cluster of distinct characteristics that tend to occur together. Usually the cause is three chromosomes at a particular location instead of the usual two (a condition called a trisomy). The most common extra-

Some 300 distinct characteristics can result from that third chromosome 21. No individual with Down syndrome is identical to another, but trisomy-

OBSERVATION QUIZ How many characteristics can you see that indicate that Daniel has Down syndrome?

Individuals with Down syndrome vary in many traits, but visible here are five common ones. Compared to most children his age, including his classmate beside him, Daniel has a rounder face, narrower eyes, shorter stature, larger teeth and tongue, and—

Many people with Down syndrome also have hearing problems, heart abnormalities, muscle weakness, and short stature. They are usually slower to develop intellectually, especially in language, and they reach their maximum intellectual potential at about age 15 (Rondal, 2010). Some are severely intellectually disabled; others are of average or above-

Problems of the 23rd Pair

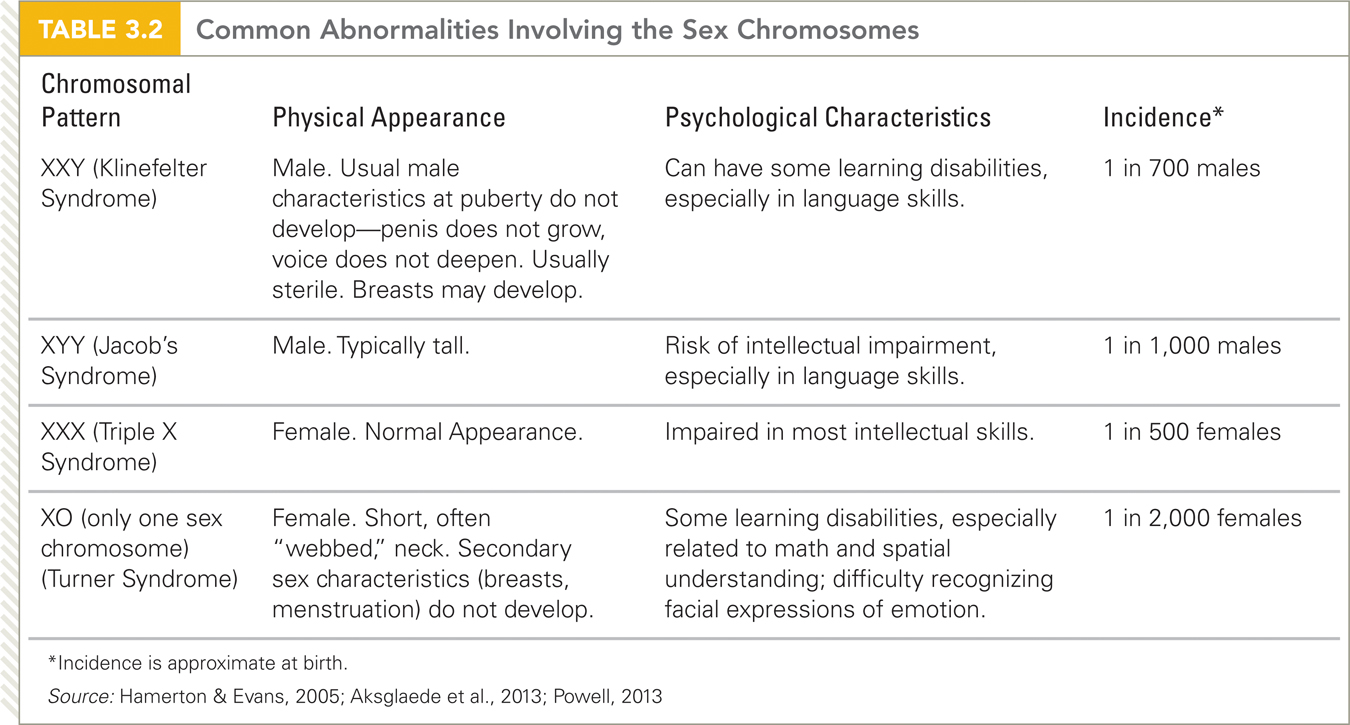

Every human has at least 44 autosomes and one X chromosome; an embryo cannot develop without those 45. However, about 1 in every 500 infants is born with only one sex chromosome (no Y) or with three or more (not just two) (Hamerton & Evans, 2005); the particular combination of sex chromosomes results in specific syndromes (see Table 3.2).

Especially for Teachers Suppose you know that one of your students has a sibling who has Down syndrome. What special actions should you take?

As the text says, “information combats prejudice.” Your first step would be to read about Down syndrome. You would learn, among other things, that it is not usually inherited (your student need not worry about his or her progeny) and that some children with Down syndrome need extra medical and educational attention. You might need to pay special attention to your student, whose parents might focus on the sibling.

Having an odd number of sex chromosomes impairs cognition and sexual maturation, with varied specifics depending on epigenetics (Hong & Reiss, 2014). It is not unusual for an affected person to seem to be developing normally until they find they are infertile. Then diagnosis reveals the undetected problem.

Gene Disorders

Especially for Future Doctors Might a patient who is worried about his or her sexuality have an undiagnosed abnormality of the sex chromosome?

That is highly unlikely. Chromosomal abnormalities are evident long before adulthood. It is quite normal for adults to be worried about sexuality for social, not biological, reasons. You could test the karyotype, but that may be needlessly alarmist.

Everyone carries alleles that could produce serious diseases or handicaps in the next generation. Most such genes have no serious consequences because they are recessive. The phenotype is affected only when the inherited gene is dominant or when a zygote is homozygous for a particular recessive condition, that is, when the zygote has received the recessive gene from both parents.

Dominant Disorders

Most of the 7,000 known single-

Severe dominant disorders become common only when they are latent in childhood, manifest in adulthood. That is the case with Huntington disease, a fatal central nervous system disorder caused by a copy number variation—

Another exception to the general rule that serious dominant diseases are not inherited is a rare but severe form of Alzheimer’s disease. It causes dementia before age 60. Most forms of Alzheimer’s, which begin after age 70, are not dominant.

Recessive Disorders

Severe recessive diseases are more numerous because they are passed down from one generation to the next by carriers who do not know they carry the recessive gene. Some such recessive conditions are X-

Fragile X syndrome is caused by more than 200 repetitions on one gene (Plomin et al., 2013). (Some repetitions are normal, but not this many.) The cognitive deficits caused by fragile X syndrome are the most common form of inherited intellectual disability (many other forms, such as trisomy-

Most recessive disorders are on the autosomes, not the X or Y (Milunsky, 2011). Carrier detection is possible for about 500 of them, and diagnosis of the actual disorder is possible for thousands of them, creating an ethical dilemma. Should someone be told about a genetic disorder if no treatment is available and if the knowledge will not change anything?

The Most Common Disorders

Some recessive diseases are very common, and that has led to research and effective treatment. About 1 in 12 North American men and women carries an allele for cystic fibrosis, thalassemia, or sickle-

To explain this benefit, consider the most studied example: sickle-

Video: Genetic Testing explores the pros and cons of knowing what diseases may eventually harm us or our unborn children.

Selective adaptation allowed the gene to become widespread because it protected more people (the carriers) than it killed (those who inherited the recessive gene from both parents). Odds were that if a couple were both carriers and had four children, one would die of sickle cell, one would not be a carrier and thus might die of malaria, but two would be carriers. These carriers would not only develop normally but they would also have added protection against a common, fatal disease, and thus they would be likely to become parents themselves. In that way, the recessive trait became widespread.

Almost every disease and risk of death is more common in one ethnic group than in another (Weiss & Koepsell, 2014). About 11 percent of Americans with African ancestors are carriers of the sickle-

Furthermore, almost every infectious disease is more or less common because of particular alleles (McLaren et al., 2013). For example, an allele provides protection against HIV. That allele is not yet common because, unlike malaria and cholera, HIV has become widespread only in the past decades. However, many scientists are working to artificially provide exactly the chemical protection that a few people have naturally.

Genetic Counseling and Testing

Until recently, after the birth of a child with a severe disorder, couples blamed witches or fate, not genes or chromosomes. That has changed, with many young adults concerned about their genes long before parenthood. Virtually everyone has a relative with a serious condition and wonders what their children will inherit. People are also curious about their own future health. Many pay for commercial genetic testing, which often provides misleading information.

Psychological Disorders

Misinformation and mistaken fears are particularly destructive for psychological disorders, such as depression, schizophrenia, and autism. No doubt genes are a factor in all of these conditions (Plomin et al., 2013). Yet, as with addiction and vision, the environment is crucial for every disorder—

This was confirmed by a study of the entire population of Denmark, where good medical records and decades of free public health allow accurate research on mental health. If both Danish parents developed schizophrenia, 27 percent of their children developed it; if one parent had it, 7 percent of their children developed it. These same statistics can be presented another way: Even if both parents developed the disease, almost three-

Even more persuasive is evidence pertaining to monozygotic twins. If one identical twin develops schizophrenia, often—

Numerous studies have identified environmental influences on schizophrenia, including fetal malnutrition, birth in the summer, adolescent use of psychoactive drugs, emigration in young adulthood, and family emotionality during adulthood. Because environment is crucial, few scientists advocate genetic testing for schizophrenia or any mental condition. They fear that a positive test would lead to depression and stress, factors that might cause a disorder that would not have appeared without the test. Further, a positive genetic diagnosis might add to the prejudice against people who become mentally ill (Mitchell et al., 2010).

The Need for Counseling

The problems with testing for genes that cause mental disorders are only one of several complications that might emerge from a societal uptick in genetic testing. Scientists—

One complication is that science has revealed much more than anyone imagined a decade ago. Laws and ethics have not kept up with the possibilities, and very few prospective parents can interpret their own genetic history or laboratory results without help. Some seek abortion or sterilization without needing such a drastic step; others blithely give birth to one impaired child after another.

Professionals trained to provide genetic counseling help prospective parents understand their genetic risk so that they can make informed decisions. The genetic counselor’s task is complicated, for many reasons. One is that testing is now possible for hundreds of conditions, but it is not always accurate.

Moreover, a particular gene might increase the risk of a problem by only a tiny amount, perhaps 0.1 percent. Further, every adult is a carrier for something. It is crucial to explain test results carefully, since many people misinterpret words such as risks and probability, especially when considering personal and emotionally charged information (O’Doherty, 2006).

Even doctors do not always understand genetics. Consider the experience of one of my students. A month before she became pregnant, Jeannette was required to have a rubella vaccination for her job. Hearing that she had had the shot, her prenatal care doctor gave her the following prognosis:

My baby would be born with many defects, his ears would not be normal, he would be intellectually disabled…. I went home and cried for hours and hours….

I finally went to see a genetic counselor. Everything was fine, thank the Lord, thank you, my beautiful baby is okay.

[Jeannette, personal communication]

It is possible that Jeannette misunderstood what she was told, but that is exactly why the doctor should not have spoken. Genetic counselors are trained to make information clear. If sensitive counseling is available, then preconception, prenatal, or even prenuptial (before marriage) testing is especially useful for:

individuals who have a parent, sibling, or child with a serious genetic condition

couples who have had several spontaneous abortions or stillbirths

couples who are infertile

couples from the same ethnic group, particularly if they are relatives

women over age 35 and men over age 40

Genetic counselors follow two ethical rules: (1) tests are confidential, beyond the reach of insurance companies and public records, and (2) decisions are made by the clients, not by the counselors.

However, these guidelines are not always easy to follow (Parker, 2012). One quandary arises when parents already have a child with a recessive disease, but tests reveal that the husband does not carry that gene. Should the counselor tell the couple that their next child will not have this disease because the husband is not the biological father of the first?

Another quandary arises when DNA is collected for one purpose—

The current consensus is that information should be shared if:

the person wants to hear it

the risk is severe and verified

an experienced counselor explains the data

treatment is available (Couzin-

Frankel, 2011)

But not everyone accepts that consensus. Scientists and physicians disagree about severity, certainty, and treatment. A group of experts recently advocated informing patients of any serious genetic disorder, even when the person does not want to know, and when the information might be harmful (Couzin-

An added complication is that individuals differ in their willingness to hear bad news. What if one person wants to know, but other family members—

Sometimes couples make a decision (such as to begin or to abort a pregnancy) that reflects a mistaken calculation of the risk, at least as the professional interprets it (Parker, 2012). Even with careful counseling, people with identical genetic conditions often make opposite choices.

For instance, 108 women who already had one child with fragile X syndrome were told they had a 50 percent chance of having another such child. Most (77 percent) decided to avoid pregnancy with sterilization or excellent contraception, but some (20 percent) deliberately had another child (Raspberry & Skinner, 2011). Always the professional explains facts and probabilities; always the clients decide.

Many developmentalists stress that changes in the environment, not in the genes, are more likely to improve health. In fact, some believe that the twenty-

As you have read many times in this chapter, genes are part of the human story, influencing every page, but they do not determine the plot or the final paragraph. The remaining chapters describe the rest of the story.

SUMMING UP Often a zygote does not have 46 chromosomes. Such zygotes rarely develop to birth. Two primary exceptions are those with Down syndrome (trisomy-

Every person is a carrier for some serious genetic conditions. Most of these conditions are rare and polygenetic. A few recessive-

For all chromosomal and genetic problems, counseling helps couples clarify their values and understand probabilities and consequences. However, the decision to conceive or abort involves personal and ethical values, so the final decision is made by those directly involved.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 3.21

Why does this textbook on normal development include abnormal development?

Studying abnormal development provides us with three things: 1) Insight into the complexities of nature and nurture; 2) Knowledge of disorders' origins to help limit their negative effects; and 3) Information to combat prejudice by demonstrating that difference is not always deficit.Question 3.22

What usually happens when a zygote has fewer or more than 46 chromosomes?

Usually, each sperm and each ovum have 23 chromosomes, and the zygote they create has 46. However, some gametes have more or less than 46 chromosomes. About 5 to 10 percent of all zygotes have more or less than 46 chromosomes. Few of these zygotes develop to birth ( less than 1 percent) , primarily because most such zygotes never duplicate, divide, and differentiate. Many of the rest are aborted spontaneously or by choice. Birth itself is hazardous; about 5 percent of stillborn babies have 47 chromosomes. Once in about every 200 births, a newborn survives with 45, 47, or rarely, 48 or 49 chromosomes. Each abnormality leads to a recognizable syndrome, a cluster of distinct characteristics that tend to occur together. Usually the cause is three chromosomes at a particular location instead of the usual two ( a condition called a trisomy) .Question 3.23

What are the consequences if a baby is born with trisomy-

21? No individual born with trisomy–21 or Down syndrome is identical to another, but most have specific facial characteristics including a thick tongue, round face, and slanted eyes. Many infants with trisomy– 21 also have hearing problems, heart abnormalities, muscle weakness, and short stature. They are usually slower to develop intellectually, especially in language, though their eventual intellect varies in part because of epigenetics and partly because of family support. Question 3.24

Why are a few recessive traits (such as sickle-

cell) quite common? The reason is evolutionary—carriers of certain recessive disorders were protected from deadly diseases. For example, sickle– cell carriers are unlikely to die from malaria, which was a major killer of those living in Africa. Question 3.25

Why are relatively few genetic conditions dominant?

Severe dominant disorders are rare because children with such disorders rarely live long enough to pass on the gene.Question 3.26

Why do people need counselors, not merely fact sheets about genetic conditions?

The counselor' s job is to make sure the person understands the facts and treatment options as well as possible outcomes of not treating a condition. It allows them to understand the difference between probabilities and certainties and to make decisions accordingly.