Birth

About 38 weeks (266 days) after conception, the fetal brain signals the release of hormones, specifically oxytocin, to prepare the fetus and mother for labor. The average baby is born after 12 hours of active labor for first births and 7 hours for subsequent births, although often birth takes twice or half as long, with biological, psychological, and social circumstances all significant. The definition of “active” labor varies, which is one reason some women believe they are in active labor for days and others say 10 minutes.

Birthing positions also vary—

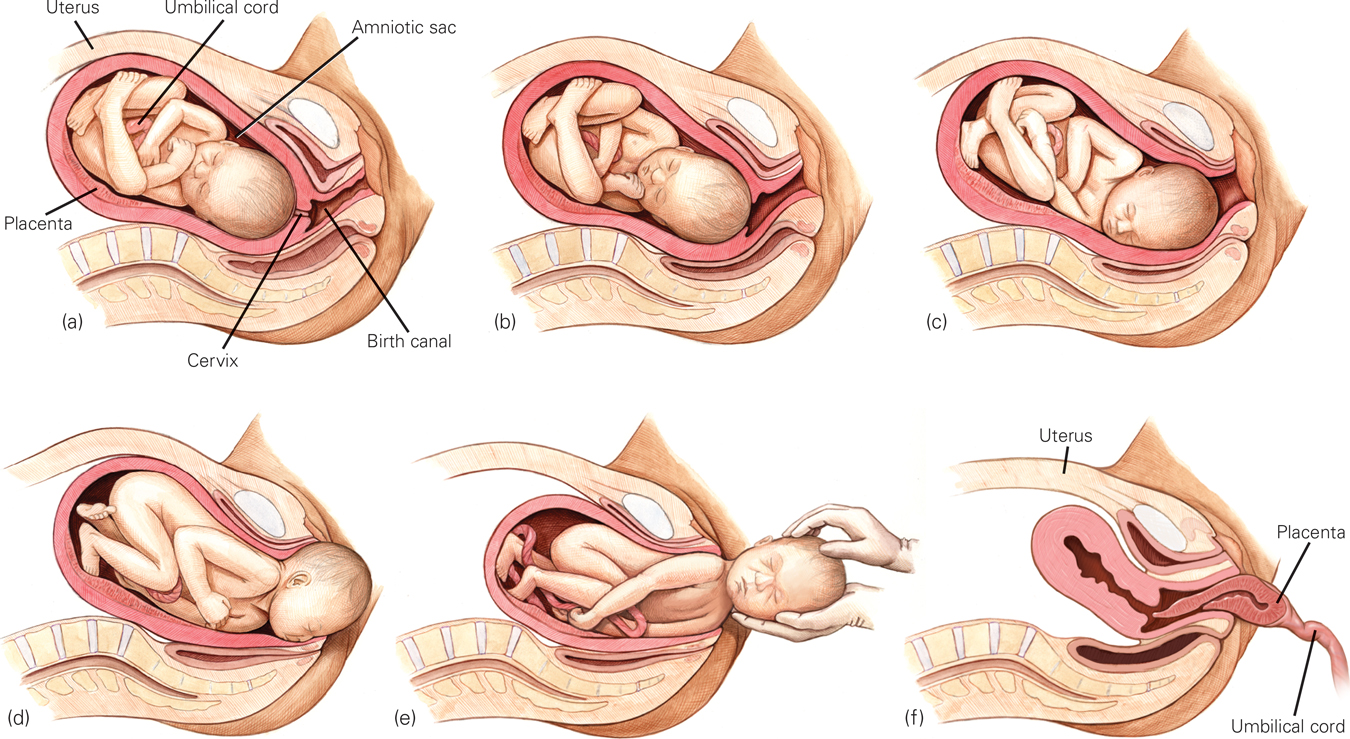

A Normal, Uncomplicated Birth (a) The baby’s position as the birth process begins. (b) The first stage of labor: The cervix dilates to allow passage of the baby’s head. (c) Transition: The baby’s head moves into the “birth canal,” the vagina. (d) The second stage of labor: The baby’s head moves through the opening of the vagina (the baby’s head “crowns”) and (e) emerges completely. (f) The third stage of labor is the expulsion of the placenta. This usually occurs naturally, but the entire placenta must be expelled, so birth attendants check carefully. In some cultures, the placenta is ceremonially buried, to commemorate its life-

The Newborn’s First Minutes

Newborns usually breathe and cry on their own. Between spontaneous cries, the first breaths of air bring oxygen to the lungs and blood, and the infant’s color changes from bluish to pinkish. (Pinkish refers to blood color, visible beneath the skin, and applies to newborns of all hues.) Eyes open wide; tiny fingers grab; even tinier toes stretch and retract. The newborn is instantly, zestfully, ready for life.

Nevertheless, there is much to be done. If birth occurs with a trained professional, mucus in the baby’s throat is removed, especially if the first breaths seem shallow or strained. The umbilical cord is cut to detach the placenta, leaving an inch or so of the cord, which dries up and falls off several days later to leave the belly button. The infant is often given to the mother to preserve its body heat and to breast-

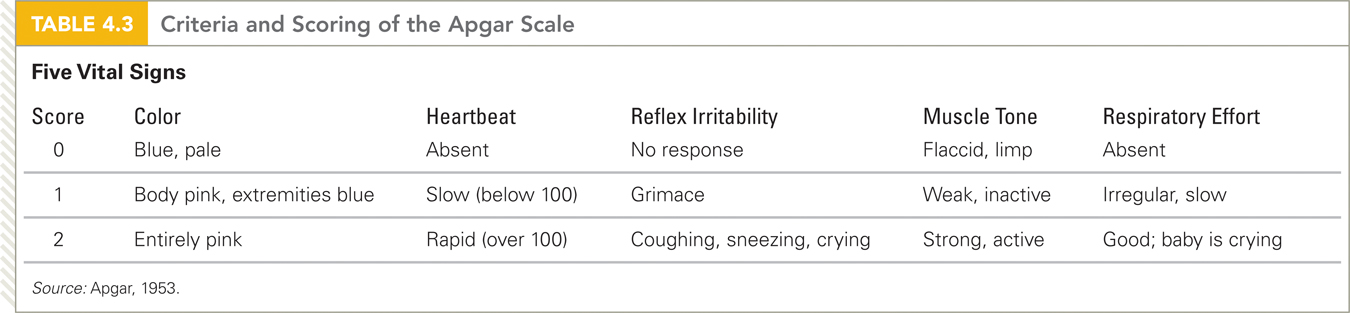

One widely used assessment of infant health is the Apgar scale (see Table 4.3), first developed by Dr. Virginia Apgar. When she earned her MD from Columbia Medical School in 1933, Apgar wanted to become a surgeon but was told that only men did surgery. Consequently, she became an anesthesiologist. She saw that “delivery room doctors focused on mothers and paid little attention to babies. Those who were small and struggling were often left to die” (Beck, 2009, p. D-

To save those young lives, Apgar developed a simple rating scale of five vital signs—

If the five-

Medical Assistance

How closely any particular birth matches the foregoing description depends on the parents’ preparation, the position and size of the fetus, and the customs of the culture.

The Cesarean

Midwives are as skilled at delivering babies as physicians, but in the United States only medical doctors are licensed to perform surgery. One-

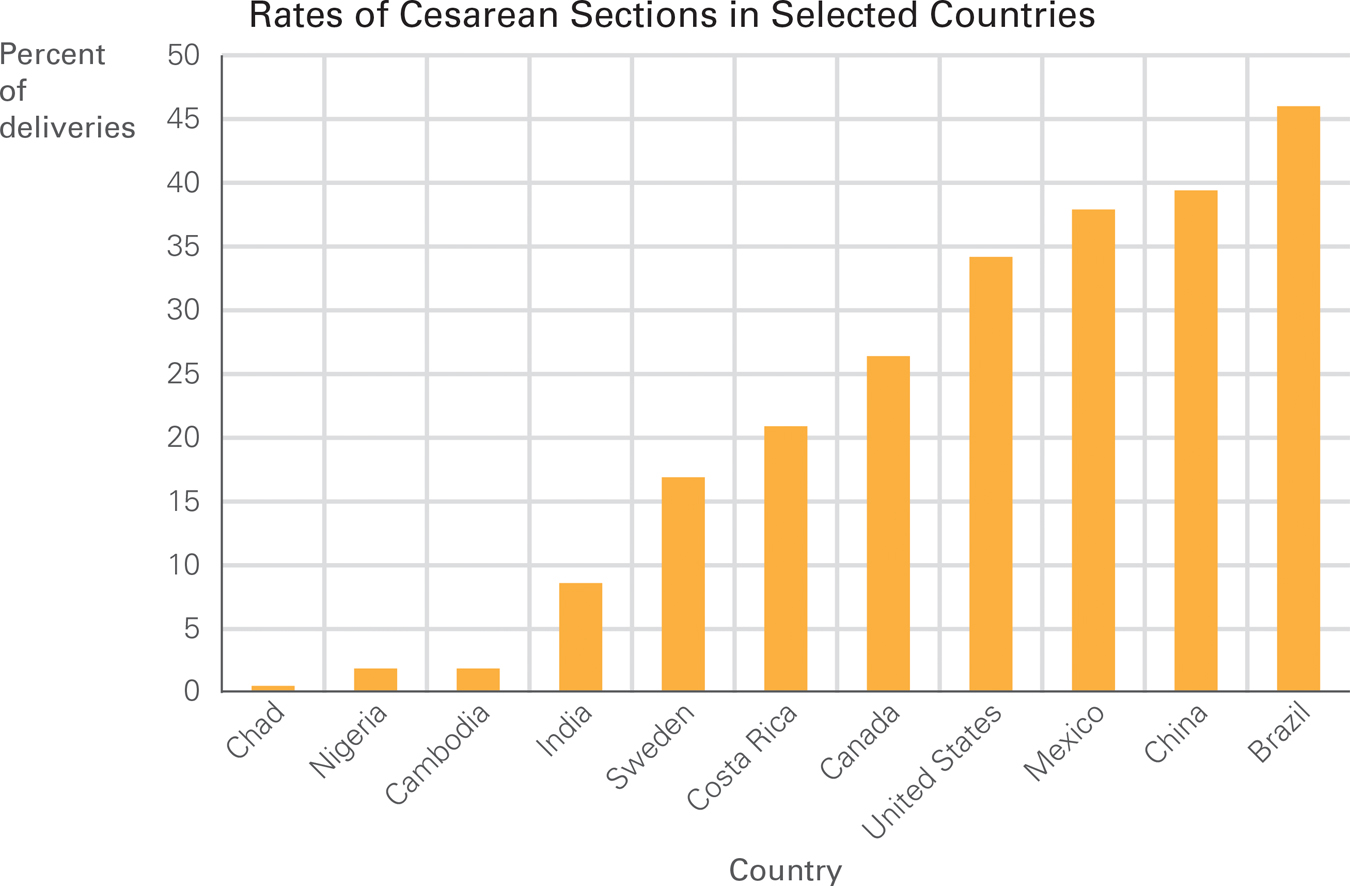

Most nations have fewer cesareans than the United States, but some—

Too Many Cesareans or Too Few? Rates of cesarean deliveries vary widely from nation to nation. Latin America has the highest rates in the world (note that 45 percent of all births in Brazil are by cesarean), and sub-

In the United States, the rate rose between 1996 and 2008 (from 21 percent to 34 percent) before stabilizing. Variation is dramatic from one hospital to another—

One reason for the rise in c-

Resch felt “a lot of rough pushing and pulling” and “a painless suction sensation” as if her body were “a tar pit the baby was wrestled from.” She heard the doctor say to the resident: “Hold her up by the hips,” and Resch peered down. She saw her daughter for the first time, wet and squirming… Resch’s husband held the baby next to Resch’s cheek. Resch felt “overwhelmed by emotions … joy, awe, anxiety, relief, surprise.” She gave thanks for her healthy baby, and for modern obstetrical care.

[Lake, 2012, p. 23]

The disadvantages appear later. C-

Newborn Survival

A century ago, at least 5 of every 100 newborns in the United States died (De Lee, 1938), as did more than half of newborns in developing nations. In the least developed nations, the rate of newborn death is now about 1 in 20, although an accurate count is not available as some rural newborn deaths are not tallied. One estimate is that worldwide almost 2 million newborns (1 in 70) die each year (Rajaratnam et al., 2010).

Every year, an estimated 273,500 women die in pregnancy or birth, almost all of them in nations with very poor medical care (Alkire et al., 2012). A suggested solution is to increase training of doctors or midwives so that cesarean sections could be more available when women were unable to deliver vaginally.

Currently in the United States, newborn mortality (when a baby is born alive but dies in the first day) is about 1 in 250—

Critics point out, however, that survival should not be the only measure of success. Several aspects of birth arise from custom or politics, not from necessity.

A particular issue in medically-

Questions of costs—

Especially for Conservatives and Liberals Do people’s attitudes about medical intervention at birth reflect their attitudes about medicine at other points in their life span, in such areas as assisted reproductive technology (ART), immunization, and life support?

Yes, some people are much more likely to want nature to take its course. However, personal experience often trumps political attitudes about birth and death; several of those who advocate hospital births are also in favor of spending one's final days at home.

A rare complication (uterine rupture), which sometimes happens when women give birth vaginally after a cesarean, has caused most doctors to insist that, after one cesarean, subsequent births must be cesarean. Many women and some experts think this is too cautious, but juries blame doctors for inaction more than for action. To avoid lawsuits, doctors intervene (Schifrin & Cohen, 2013).

Most U.S. births now take place in hospital labor rooms with high-

Compared with the United States, planned home births are more common in many other developed nations (2 percent in England, 30 percent in the Netherlands) where midwives are paid by the government. In the Netherlands, special ambulances called flying storks speed mother and newborn to a hospital if needed. Dutch research finds home births better for mothers and no worse for infants than hospital births (de Jonge et al., 2013).

A crucial question is how supportive the medical professionals are. One committee of obstetricians decided that planned home births are acceptable because women have “a right to make a medically informed decision about delivery,” but they also insisted that a trained midwife or doctor be present, that the woman not be high-

Historically, women in hospitals labored by themselves until birth was imminent; fathers and other family members were kept away. No longer, as the opening anecdote illustrates. Almost everyone now agrees that a laboring woman should never be alone.

Many women have a doula, a person trained to support the laboring woman. Doulas time contractions, use massage, provide encouragement, and do whatever else is helpful. Every comparison study finds that the rate of medical intervention is lower when doulas are part of the birth team. Doulas have proven to be particularly helpful for immigrant, low-

OBSERVATION QUIZ What evidence shows that even in Hanoi, technology is part of this birth?

The computer print–

SUMMING UP Most newborns score at least 7 out of 10 on the Apgar scale and thrive without medical assistance. If necessary, neonatal surgery and intensive care save lives. Although modern medicine has reduced maternal and newborn deaths, many critics deplore treating birth as a medical crisis rather than a natural event. Responses to this critique include women choosing to give birth in hospital labor rooms rather than operating rooms, in birthing centers instead of hospitals, or even at home. The assistance of a doula is another recent practice that reduces medical intervention.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 4.6

Why has the Apgar scale increased newborns’ survival rate?

The Apgar scale alerts doctors to the condition of a newborn who needs medical attention.Question 4.7

Why has the rate of cesarean sections increased?

Cesareans make scheduling a baby's delivery easier than the unpredictable vaginal birth, and the actual delivery is quicker than a vaginal birth. Cesareans also carry an added bonus for the hospital since they are quite expensive.Question 4.8

Why are developmentalists concerned that surgery is often part of birth?

C–sections are warranted in only about 15 percent of births. While they are generally safe, they are often performed for convenience's sake. However, they result in more complications after birth and reduce breast– feeding. By age 3, children born by cesarean have double the rate of childhood obesity compared to those born vaginally. Question 4.9

Why are home births more common in some nations than others?

Most U.S. births now take place in hospital labor rooms with high–tech operating rooms nearby in case they are needed. Another 5 percent of U.S. births occur in birthing centers (not in a hospital), and less than 1 percent occur at home (home births are illegal in some jurisdictions). About half of the home births are planned and half not because of unexpectedly rapid labor. The unplanned ones are hazardous if no one is nearby to rescue a newborn in distress. Compared with the United States, planned home births are more common in many other developed nations (2 percent in England, 30 percent in the Netherlands) where midwives are paid by the government. In the Netherlands, special ambulances called flying storks speed mother and newborn to a hospital if needed. Dutch research finds home births better for mothers and no worse for infants than hospital births. Question 4.10

Why do women choose to have a doula in addition to a midwife or doctor?

Many women have a doula, a person trained to support the laboring woman. Doulas time contractions, use massage, provide encouragement, and do whatever else is helpful. Every comparison study finds that the rate of medical intervention is lower when doulas are part of the birth team. Doulas have proven to be particularly helpful for immigrant, low–income, or unpartnered women who may be intimidated by doctors.