Harm to the Fetus

The early days of life place the developing human on the path toward health and success—

Harmful Substances

A cascade may begin before a woman realizes she is pregnant, as many toxins, illnesses, and experiences can cause harm early in pregnancy. Every week, scientists discover an unexpected teratogen, which is anything—

One of my students told me that she now knew all the things that can go wrong, so she never wanted to have a baby. As I explained to her and as you will now read, most problems can be avoided, mitigated, or remedied. Prenatal life is not a dangerous period to be feared; it is a natural process to be protected. The outcome is usually a wonderfully formed newborn.

Behavioral Teratogens

Some teratogens cause no physical defects but affect the brain, making a child hyperactive, antisocial, or learning-

I was nine years old when my mother announced she was pregnant. I was the one who was most excited…. My mother was a heavy smoker, Colt 45 beer drinker and a strong caffeine coffee drinker.

One day my mother was sitting at the dining room table smoking cigarettes one after the other. I asked “Isn’t smoking bad for the baby? She made a face and said “Yes, so what?”

I said “So why are you doing it?”

She said, “I don’t know.”…

During this time I was in the fifth grade and we saw a film about birth defects. My biggest fear was that my mother was going to give birth to a fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) infant…. My baby brother was born right on schedule. The doctors claimed a healthy newborn…. Once I heard healthy, I thought everything was going to be fine. I was wrong, then again I was just a child….

My baby brother never showed any interest in toys…. [H]e just cannot get the right words out of his mouth…. [H]e has no common sense….

Why hurt those who cannot defend themselves?

[J., personal communication]

Especially for Judges and Juries How much protection, if any, should the legal system provide for fetuses? Should pregnant women with alcoholism be jailed to prevent them from drinking? What about people who enable them to drink, such as their partners, their parents, bar owners, and bartenders?

Some laws punish women who jeopardize the health of their fetuses, but a developmental view would consider the micro-

As you remember from Chapter 1, one case proves nothing. J. blames her mother, although genes, postnatal experiences, and lack of preventive information and services may be part of the cascade as well. Nonetheless, J. rightly wonders why her mother took a chance.

Behavioral teratogens can be subtle, yet their effects may last a lifetime. That is one conclusion from research on the babies born to pregnant women exposed to flu during the pandemic of 1918. By middle age, although some of these babies became wealthy, happy, and brilliant, on average those born in flu-

Risk Analysis

Life requires risks: We analyze which chances to take and how to minimize harm. To pick an easy example: Crossing the street is risky. Knowing that, we cross carefully; it would be much more harmful to stay on our block.

Risk analysis is crucial throughout human development (Sheeran et al., 2014). You read in Chapter 3 that pregnancy after age 35 increases the chance of many disorders, but mature parents are more likely to have many assets, psychological as well as material, that benefit their children. Depending on many aspects of the social context, it may be wise to have a baby at age 18 or 42 or any other age. Always, risk analysis is needed; many problems can be prevented or overcome.

Although all teratogens increase the risk of harm, none always causes damage; risk analysis involves probabilities, not certainties, and resilient and protective influences are relevant (Aven, 2011). The impact of teratogens depends on the interplay of many factors, both destructive and constructive, an example of the dynamic-

The Critical Time

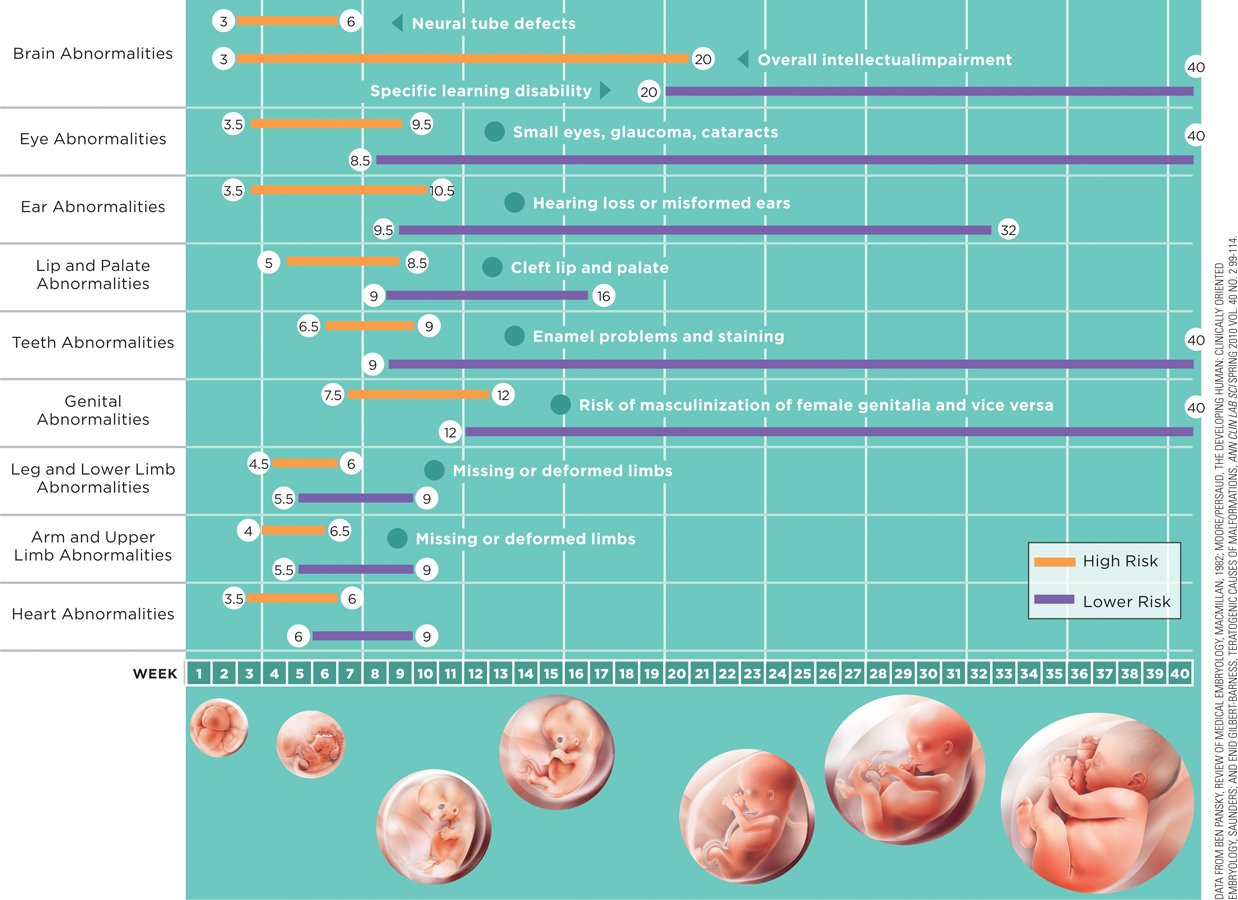

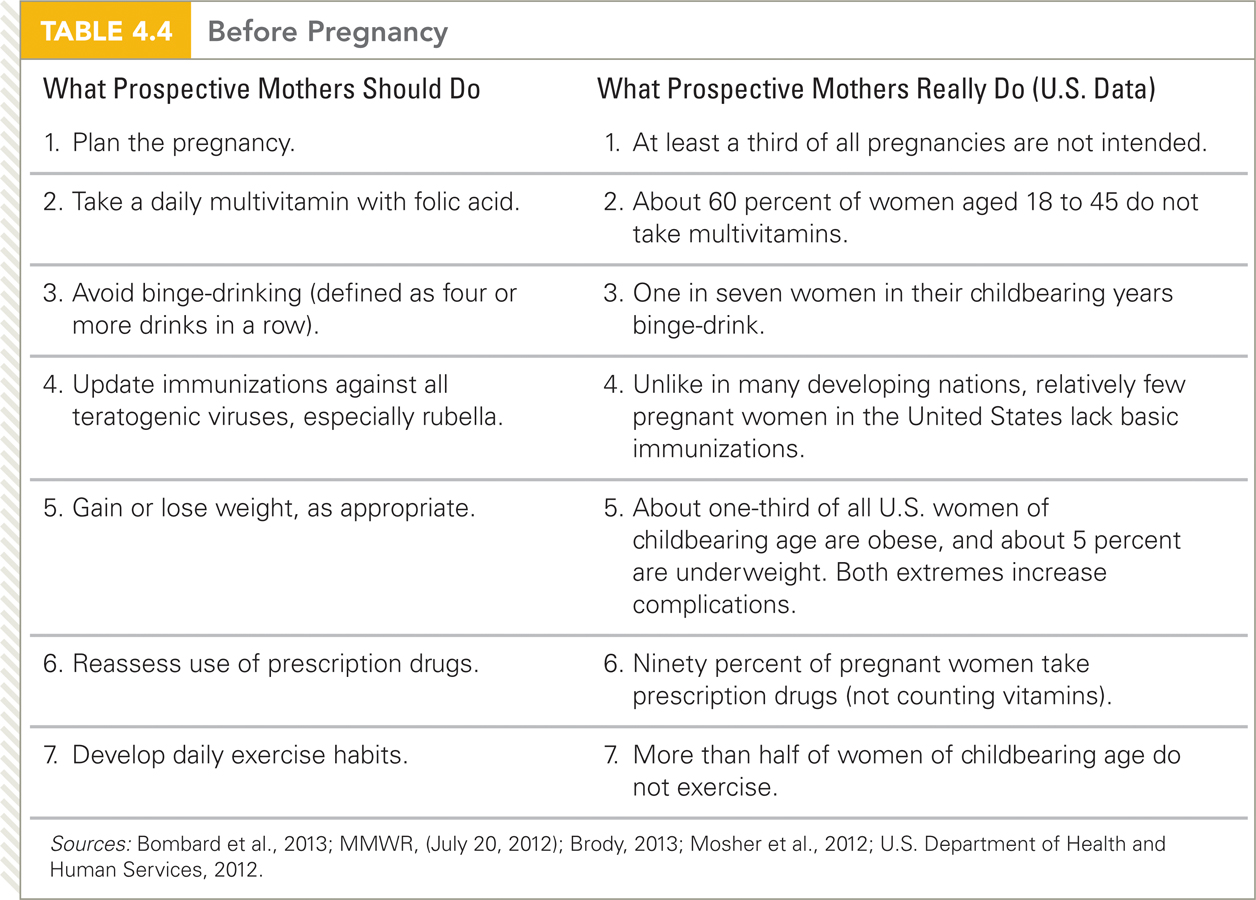

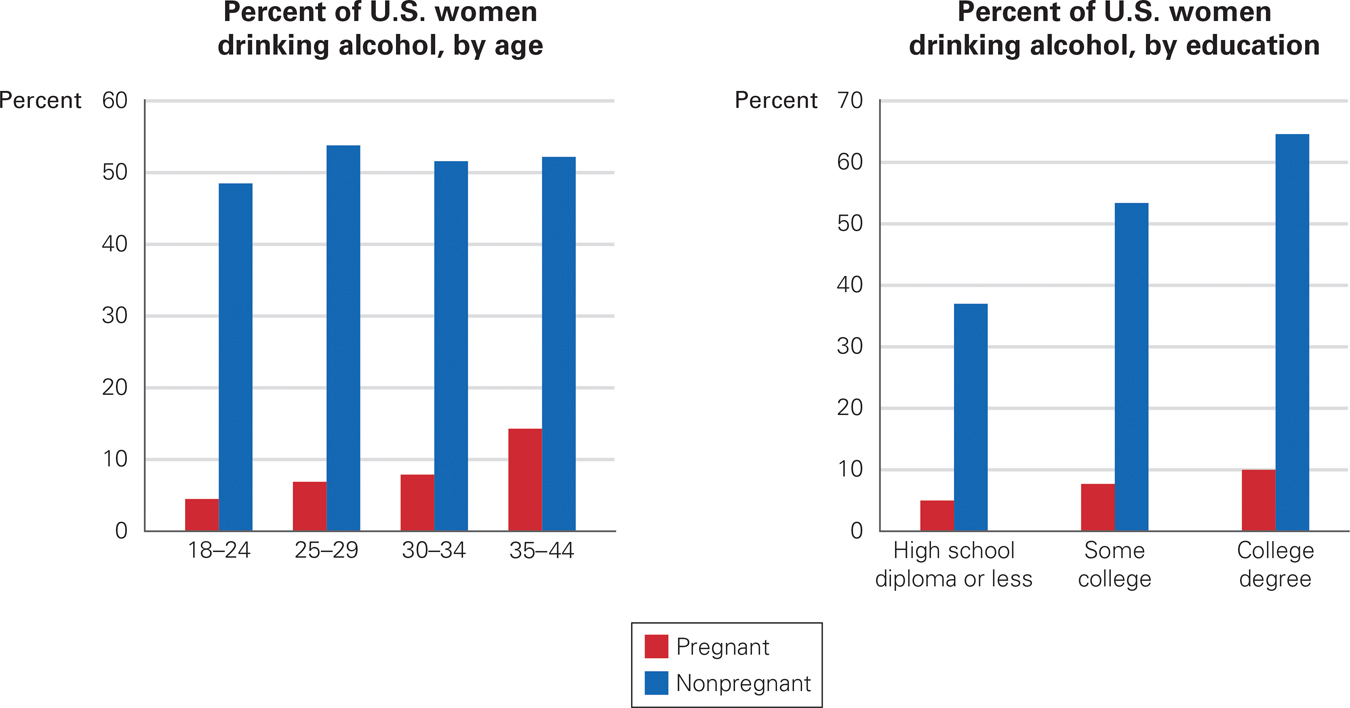

Timing is crucial. Some teratogens cause damage only during a critical period (see Figure 4.5). (Developmental Link: Critical and sensitive periods are described in Chapter 1.) Obstetricians recommend that before pregnancy occurs, women should avoid drugs (especially alcohol), supplement a balanced diet with extra folic acid and iron, update their immunizations, and gain or lose weight if needed. Indeed, pre-

The embryonic period (from the third to the eight week) is the most sensitive time for causing structural birth defects. Organs have different periods of sensitivity to birth defects: Some are vulnerable for a long time (e.g., the brain), others for a shorter time (e.g., the arms). The embryonic period (weeks 3 to 8) is the most sensitive time for structural birth defects. During the fetal period, the brain is the most at risk for defects. Sometimes teratogens can affect multiple organs at the same time. Individual differences in susceptibility to teratogens may be caused by a fetus’s genetic makeup or peculiarities of the mother, including the effectiveness of her placenta or her overall health. The dose and timing of the exposure are both important.

The first days and weeks after conception (the germinal and embryonic periods) are critical for body formation, but health during the entire fetal period affects the brain, and thus behavioral teratogens affect the fetus at any time. Some teratogens that cause preterm birth or low birthweight are particularly harmful in the second half of pregnancy.

In fact, one study found that although smoking cigarettes throughout prenatal development can harm the fetus, smokers who quit early in pregnancy had no higher risks of birth complications than did women who never smoked (McCowan et al., 2009). Another longitudinal study of 7-

How Much Is Too Much?

A second factor affecting the harm from teratogens is the dose and/or frequency of exposure. Some teratogens have a threshold effect they are virtually harmless until exposure reaches a certain level, at which point they “cross the threshold” and become damaging. This threshold is not a fixed boundary: Dose, timing, frequency, and other teratogens affect when the threshold is crossed (O’Leary et al., 2010).

A few substances are beneficial in small amounts but fiercely teratogenic in large quantities. Vitamin A, for instance, is essential for healthy development but causes abnormalities if the dose is 50,000 units per day or higher (obtained only in pills, don’t worry about eating carrots) (Naudé et al., 2007). Experts rarely specify thresholds, partly because one teratogen may affect the threshold of another. Alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana are more teratogenic, with a lower threshold for each, when all three are combined.

Is there a safe dose for psychoactive drugs? Consider alcohol. During the period of the embryo, a mother’s heavy drinking can cause fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which distorts the facial features of a child (especially the eyes, ears, and upper lip). Later in pregnancy, alcohol is a behavioral teratogen.

However, alcohol during pregnancy does not always result in evident harm. If it did, almost everyone born in Europe before 1980 would be affected, since wine or beer was part of most Europeans’ daily diet.

Currently, pregnant women are advised to avoid alcohol, but women in the United Kingdom receive conflicting advice about drinking an occasional glass of wine (Raymond et al., 2009). French women are told to abstain, but many (between 12 and 63 percent, depending on specifics of the research) do not heed that message (Dumas et al., 2014). Should all women who might become pregnant refuse a legal substance that men use routinely? Wise? Probably. Necessary? Maybe not.

Innate Vulnerability

Genes are a third factor that influence the effects of teratogens. When a woman carrying dizygotic twins drinks alcohol, for example, the twins’ blood alcohol levels are equal; yet one twin may be more severely affected than the other because their alleles for the enzyme that metabolizes alcohol differ. Differential susceptibility is evident for fetal alcohol disorders, and probably for many other problems as well (McCarthy & Eberhart, 2014).

The Y chromosome may make male fetuses more vulnerable to many problems. Boys are more likely to be spontaneously aborted or stillborn and also more likely to be harmed by teratogens than female fetuses are. This is true overall, but the male/female hazard rate differs from one teratogen to another (Lewis & Kestler, 2012).

Genes are important not only at conception but also during pregnancy. One maternal allele results in low levels of folic acid in a woman’s bloodstream and hence in the embryo, which can produce neural-

Especially for Nutritionists Is it beneficial that most breakfast cereals are fortified with vitamins and minerals?

Useful, yes; optimal, no. Some essential vitamins are missing (too expensive), and individual nutritional needs differ, depending on age, sex, health, genes, and eating habits. The reduction in neural-

Since 1998 in the United States, manufacturers have had to add folic acid to every packaged cereal, an intervention that reduced neural-

Applying the Research

Results of teratogenic exposure cannot be predicted precisely in individual cases. However, much is known about destructive and damaging teratogens, including what individuals and society can do to reduce the risks. Table 4.5 lists some teratogens and their possible effects, as well as preventive measures.

General health during pregnancy is at least half the battle. Women who maintain good nutrition and avoid drugs and teratogenic chemicals (which are often found in pesticides, cleaning fluids, and cosmetics) usually have healthy babies. Some medications are necessary (e.g., for women with epilepsy, diabetes, and severe depression), but consultation should begin before conception.

Many women assume that herbal medicines or over-

Sadly, a cascade of teratogens is most likely to begin with women who are already vulnerable. For example, cigarette smokers are more often drinkers (as was J.’s mother), and those whose jobs require exposure to chemicals and pesticides (such as migrant workers) are more often malnourished and lack access to medical care (McLaurin, 2014).

a view from science

Conflicting Advice

Pregnant women want to know about the thousands of drugs, chemicals, and diseases that might harm the fetus, yet, as explained in Chapter 1, the scientific method is designed to be cautious. It takes years for replication, data from alternate designs, and exploration of various hypotheses to reach sound conclusions.

On almost any issue, scientists disagree until the weight of evidence is unmistakable. It took decades before all researchers agreed on such (now obvious) teratogens as rubella and cigarettes.

One current dispute is whether pesticides should be allowed on the large farms that produce most of the fruits and vegetables for consumption in the United States. No biologist doubts that pesticides harm frogs, fish, and bees, but the pesticide industry insists that careful use (e.g., spraying on plants, not workers) does not harm people. Developmentalists, however, worry that pregnant women who breathe these toxins might have children with brain damage. As one scientist said “pesticides were designed to be neurotoxic. Why should we be surprised if they cause neurotoxicity?” (Lambhear, quote in Mascarelli, 2013, p. 741).

Scientists have convinced the U.S. government to ban one pesticide, chlorpyrifos, from household use (it once was commonly used to kill roaches and ants), but that drug is still widely used in agriculture and is used in homes in other nations. There is evidence from analyzing blood in the umbilical cord that many fetuses are exposed to chlorpyrifos, and longitudinal research finds that these children have lower intelligence and more behavior problems than other children (Horton et al., 2012). However, Dow Chemical Company, which sells the pesticide, argues that the research does not take into account all the confounding factors, such as the living conditions of farm-

In this dispute, developmentalists choose to protect the fetal brain, which is why this chapter advises pregnant women to avoid pesticides. However, on many other teratogens, developmentalists themselves are conflicted. Fish consumption and exposure to plastics are examples.

Pregnant women in the United States are told to eat less fish, but those in the United Kingdom are told to eat more fish. The reason for these opposite messages is that fish contains mercury (a teratogen) and DHA (an omega-

Another dispute involves bisphenol A (commonly used in plastics), banned in Canada but allowed in the United States. Traces of the substance are found in the urine of most pregnant women, but most scientists think that very low amounts are harmless. The question is, where is the threshold?

Many experiments on rodents find bisphenol A teratogenic. For example, when pregnant rats are exposed to bisphenol A, even low doses affect sexual organs (Christiansen et al., 2014).

Confirmation regarding the effects of exposure on humans is difficult. Controlled experiments are unethical: No one would deliberately raise bisphenol A levels in pregnant women to see if it harmed their offspring. Surveys give conflicting results, partly because other key variables—

To make all this more difficult, pregnant women are, ideally, happy and calm: Stress and anxiety affect the fetus. Pregnancy often increases fear and anxiety (Rubertsson et al., 2014); scientists do not want to add to the worry. Prospective parents want clear, immediate answers, yet scientists cannot always provide them.

Advice from Doctors

Video Activity: Teratogens explores the factors that enable or prevent teratogens from harming a developing fetus.

Although prenatal care is helpful in protecting the developing fetus, even doctors are not always careful. One concern is pain medication. Opioids (narcotics) may do damage to the fetus and aspirin may cause excessive bleeding during birth. Yet a recent study found that 23 percent of pregnant women on Medicaid are given a prescription for a narcotic (Desai et al., 2014).

Worse still is that some doctors do not ask women about harmful life patterns. For example, one Maryland study found that almost one-

To learn what medications are safe in pregnancy, women often consult the Internet. However, a study of 25 websites that together listed 235 medications as safe, found that only 103 of those 235 had been assessed by TERIS (a respected national panel of teratologists who evaluate the impact of drugs on prenatal development). Further, of those 103, only 60 were considered safe. The rest were not proven harmful, but the experts felt there was not enough evidence to state they were safe (Peters et al., 2013). Many of these 25 Internet sites used unreliable evidence, and sometimes the same drug was on the safe list of one site and the danger list of another.

What Do We Know?

Now we know that prenatal teratogens can cause structural problems during the embryonic period and several diseases throughout pregnancy, as well as behavioral problems and reproductive impairment later in life. But it is not easy to know which teratogens, at what doses, when, and for whom. Almost every common disease, almost every food additive, most prescription and nonprescription drugs (even caffeine and aspirin), many minerals and chemicals in the air and water, emotional stress, exhaustion, and poor nutrition might impair prenatal development—

Most research is conducted with mice; harm to humans is rarely proven to everyone’s satisfaction. That is not surprising, since hundreds of thousands of drugs, diseases, and pollutants are now evident, many of them newly developed or newly diagnosed. It takes careful, replicated research before scientists reach a consensus, and then wide communication before women are aware of risks.

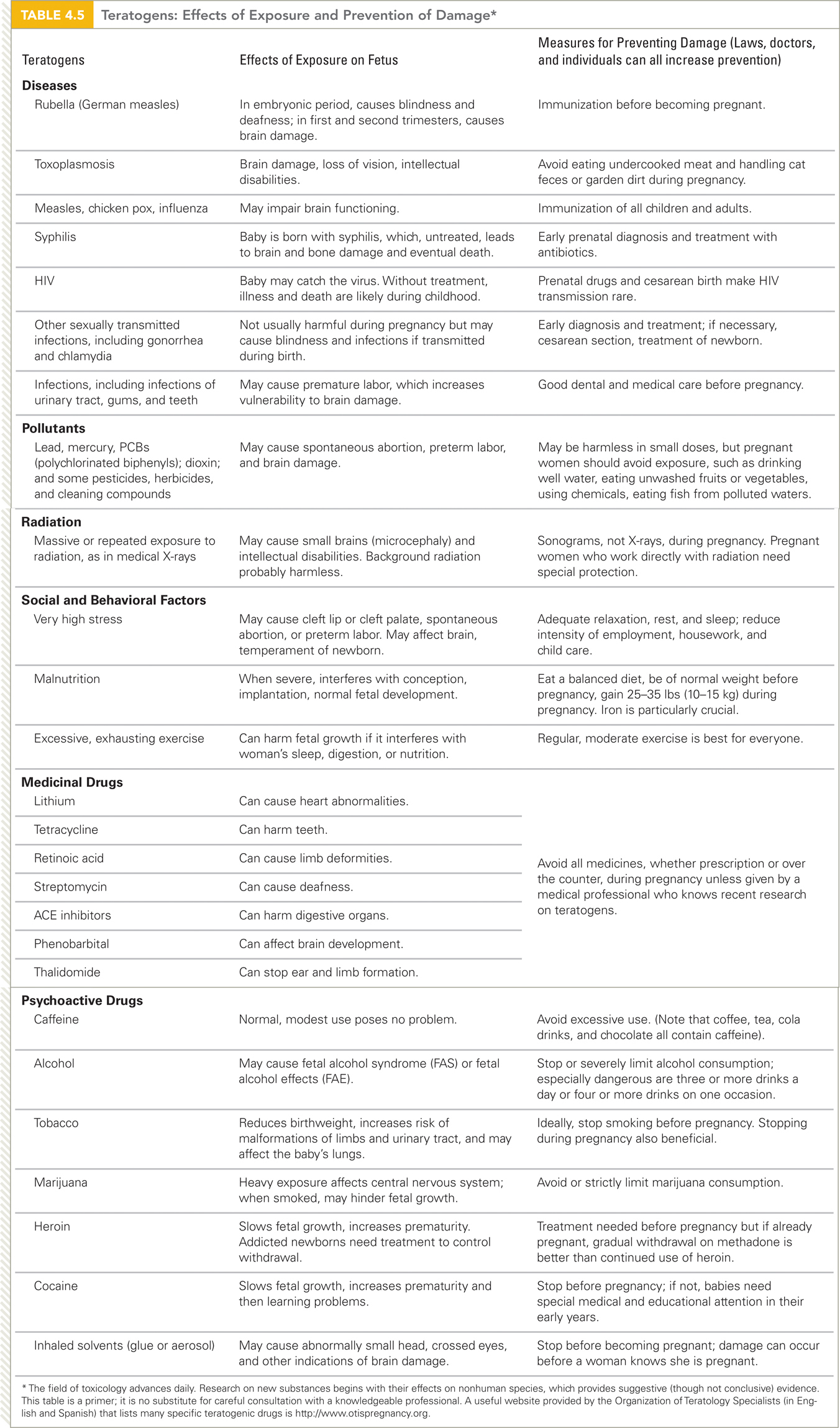

Even for proven risks, as with alcohol and cigarettes, many pregnant women are not convinced. In the United States, from 2006 to 2010, nearly 8 percent of pregnant women drank alcohol, with rates higher (10 percent) among women with a college degree (see Figure 4.6).

Trouble Ahead About half of U.S. women drink alcohol. That is not troubling, since occasional drinking in adulthood seems harmless. Most women stop drinking when they are pregnant. This is what almost all experts recommend, since drinking increases the risk of facial abnormalities in the first trimester and of brain damage throughout. The pregnant rates here are of women still reporting “any use” of alcohol in the third trimester. The data is frightening, since most neurons of the prefrontal cortex develop in the final months of pregnancy. Apparently, older is not wiser, and education does not lead to abstinence—

Furthermore, even when evidence seems clear, the proper social response is controversial. It is legal to arrest and jail pregnant women who use alcohol or other psychoactive drugs in six states (Minnesota, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Wisconsin).

If a baby is stillborn and the mother used meth, she may be convicted of murder, as occurred for an Oklahoma woman, Theresa Hernandez, who was sentenced to 15 years (Fentiman, 2009). Alabama jailed several new mothers because their babies had illegal substances in their bloodstream (Eckholm, 2013). Many doctors and developmentalists worry that such penalties make women reluctant to see a doctor when they are pregnant, or even to have the baby in a hospital.

Prenatal Care

Especially for Social Workers When is it most important to convince women to be tested for HIV: before pregnancy, after conception, or immediately after birth?

Testing and then treatment are useful at any time because women who know they are HIV-

Seeing a medical professional in the first trimester has many benefits: Women learn what to eat, what to do, and what to avoid. Some serious conditions, syphilis and HIV among them, can be diagnosed and treated before they harm the fetus. Prenatal tests (of blood, urine, and fetal heart rate as well as ultrasound) reassure parents, facilitating the crucial parent-

In general, early care protects fetal growth, makes birth easier, and renders parents better able to cope. When complications (such as twins, gestational diabetes, and infections) arise, early recognition increases the chance of a healthy birth. As birth approaches, prospective parents often attend classes where they learn about the birth process, including what they can do in the final weeks and hours, and that itself reduces confusion and increases the odds of a healthy newborn.

Unfortunately, however, about 20 percent of early pregnancy tests raise anxiety instead of reducing it. For instance, the level of alpha-

opposing perspectives

“What Do People Live to Do?”

John and Martha, both under age 35, were expecting their second child. Martha’s initial prenatal screening revealed low alpha-

Another blood test was scheduled…. John asked:

“What exactly is the problem?” …

“We’ve got a one in eight hundred and ninety-

John smiled, “I can live with those odds.”

“I’m still a little scared.”

He reached across the table for my hand. “Sure,” he said, “that’s understandable. But even if there is a problem, we’ve caught it in time…. The worst-

“I might have to have an abortion?” The chill inside me was gone. Instead I could feel my face flushing hot with anger. “Since when do you decide what I have to do with my body?”

John looked surprised. “I never said I was going to decide anything,” he protested. “It’s just that if the tests show something wrong with the baby, of course we’ll abort. We’ve talked about this.”

“What we’ve talked about,” I told John in a low, dangerous voice, “is that I am pro-

“You used to be,” said John.

“I know I used to be.” I rubbed my eyes. I felt terribly confused. “But now … look, John, it’s not as though we’re deciding whether or not to have a baby. We’re deciding what kind of baby we’re willing to accept. If it’s perfect in every way, we keep it. If it doesn’t fit the right specifications, whoosh! Out it goes.”…

John was looking more and more confused. “Martha, why are you on this soapbox? What’s your point?”

“My point is,” I said, “that I’m trying to get you to tell me what you think constitutes a ‘defective’ baby. What about … oh, I don’t know, a hyperactive baby? Or an ugly one?”

“They can’t test for those things and—

“Well, what if they could?” I said. “Medicine can do all kinds of magical tricks these days. Pretty soon we’re going to be aborting babies because they have the gene for alcoholism, or homosexuality, or manic depression…. Did you know that in China they abort a lot of fetuses just because they’re female?” I growled. “Is being a girl ‘defective’ enough for you?”

“Look,” he said, “I know I can’t always see things from your perspective. And I’m sorry about that. But the way I see it, if a baby is going to be deformed or something, abortion is a way to keep everyone from suffering—

“… And what is it,” I said softly, more to myself than to John, “what is it that people do? What do we live to do, the way a horse lives to run?”

[Beck, 1999, pp. 132–

The second AFP test was in the normal range, “meaning there was no reason to fear … Down syndrome” (p. 137).

As you read in Chapter 3, genetic counselors help couples discuss their choices before becoming pregnant. John and Martha had had no counseling because the pregnancy was unplanned and their risk for Down syndrome was low. The opposite of a false positive is a false negative, a mistaken assurance that all is well. Amniocentesis later revealed that the second AFP was a false negative. Their fetus had Down syndrome after all.

Complications During Birth

Any birth complication usually has multiple causes: A fetus is low birthweight, preterm, genetically vulnerable, or exposed to teratogens, and a mother is unusually young, old, small, stressed, or ill. As an example, cerebral palsy (a disease marked by difficulties with movement) was once thought to be caused solely by birth procedures (excessive medication, slow breech birth, or use of forceps to pull the fetal head through the birth canal). However, we now know that cerebral palsy results from genetic sensitivity, teratogens, and maternal infection (Mann et al., 2009), worsened by insufficient oxygen to the fetal brain at birth.

A lack of oxygen is anoxia. Anoxia often occurs for a second or two during birth, indicated by a slower fetal heart rate, with no harm done. To prevent prolonged anoxia, the fetal heart rate is monitored during labor and the Apgar is used immediately after birth.

Again, however, anoxia is only part of a cascade. How long anoxia can continue without harming the brain depends on genes, birthweight, gestational age, drugs in the bloodstream (either taken by the mother before birth or given during birth), and many other factors. Thus, anoxia is part of a cascade of factors that may cause cerebral palsy. Almost every birth complication is the result of a similar cascade.

SUMMING UP Risk analysis is complex but necessary to protect every fetus. Many factors reduce risk, including the mother’s health and nourishment before pregnancy, her early prenatal care and drug use, and the father’s support. Each teratogen may harm the fetus, although, as risk analysis implies, the impact varies from none at all to very serious. The timing of exposure, the amount of toxin ingested, and the genes of the mother and fetus are crucial factors.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 4.11

Why is risk analysis more crucial than targeting any one teratogen?

Risk analysis is crucial throughout human development. For example, pregnancy after age 35 increases the chance of many disorders, but mature parents are more likely to have many assets, psychological as well as material, that benefit their children. Depending on many aspects of the social context, it may be wise to have a baby at age 18 or 42 or any other age. Always, risk analysis is needed; many problems can be prevented or overcome. Although all teratogens increase the risk of harm, none always causes damage; risk analysis involves probabilities, not certainties, and resilient and protective influences are relevant. The impact of teratogens depends on the interplay of many factors, both destructive and constructive.Question 4.12

When are teratogens most harmful to the future baby?

Timing is crucial. Some teratogens cause damage only during a critical period. The first days and weeks after conception (the germinal and embryonic periods) are critical for body formation, but health during the entire fetal period affects the brain, and thus behavioral teratogens affect the fetus at any time. Some teratogens that cause preterm birth or low birthweight are particularly harmful in the second half of pregnancy. In fact, one study found that although smoking cigarettes throughout prenatal development can harm the fetus, smokers who quit early in pregnancy had no higher risks of birth complications than did women who never smoked. Another longitudinal study of 7–year– olds found that, although alcohol is a teratogen at every period of pregnancy, binge drinking in the last trimester was more harmful to the brain. Question 4.13

Why is it difficult to pin down the impact of behavioral teratogens?

Behavioral teratogens can have subtle effects that may not be apparent or may not impact an individual until later childhood.Question 4.14

What is a specific example of the impact of genes on birth defects?

Genes are important not only at conception but also during pregnancy. One maternal allele results in low levels of folic acid in a woman's bloodstream and hence in the embryo, which can produce neural–tube defects— either spina bifida, in which the tail of the spine is not enclosed properly (enclosure normally occurs at about week 7), or anencephaly, when part of the brain is missing. Question 4.15

How do doctors protect the fetus, and when might a doctor do harm?

Although prenatal care is helpful in protecting the developing fetus, even doctors are not always careful. One concern is pain medication. Opioids (narcotics) may do damage to the fetus and aspirin may cause excessive bleeding during birth. Yet a recent study found that 23 percent of pregnant women on Medicaid are given a prescription for a narcotic. Worse still is that some doctors do not ask women about harmful life patterns. For example, one Maryland study found that almost one–third of pregnant women were not asked about their alcohol use. Those who were over age 35 and college educated were least likely to be queried. Question 4.16

What factors increase or decrease the risk of spina bifida?

One maternal allele results in low levels of folic acid in a woman's bloodstream and hence in the embryo, which can produce neural–tube defects, including spina bifida, in which the tail of the spine is not enclosed properly. Neural– tube defects are more common in certain ethnic groups (Irish, English, and Egyptian), but the crucial maternal allele is rare among Asians and sub– Saharan Africans. Since 1998 in the United States, manufacturers have had to add folic acid to every packaged cereal, an intervention that reduced neural– tube defects by 26 percent in the first three years after the law went into effect. But some women rarely eat cereal and do not take vitamins. Data by region is not always available, but in 2010 in Appalachia (where many women are of British descent), about 1 newborn in 1,000 had a neural– tube defect. Question 4.17

How do anoxia and cerebral palsy illustrate the need for risk analysis?

Any birth complication usually has multiple causes, which is why risk analysis is crucial. As an example, cerebral palsy (a disease marked by difficulties with movement) was once thought to be caused solely by birth procedures (excessive medication, slow breech birth, or use of forceps to pull the fetal head through the birth canal). However, we now know that cerebral palsy results from genetic sensitivity, teratogens, and maternal infection worsened by insufficient oxygen to the fetal brain at birth. In another example, lack of oxygen can cause anoxia. Anoxia often occurs for a second or two during birth, indicated by a slower fetal heart rate, with no harm done. To prevent prolonged anoxia, the fetal heart rate is monitored during labor and the Apgar is used immediately after birth. Again; however, anoxia is only part of a cascade. How long anoxia can continue without harming the brain depends on genes, birthweight, gestational age, drugs in the bloodstream (either taken by the mother before birth or given during birth), and many other factors. Thus, anoxia is part of a cascade of factors that may cause cerebral palsy.