Low Birthweight: Causes and Consequences

Some newborns are small and immature. With modern hospital care, tiny infants usually survive, but it would be better for everyone—

The World Health Organization defines low birthweight (LBW) as under 2,500 grams. LBW babies are further grouped into very low birthweight (VLBW), under 1,500 grams (3 pounds, 5 ounces), and extremely low birthweight (ELBW), under 1,000 grams (2 pounds, 3 ounces). It is possible for a newborn to weigh as little as 500 grams, and they are the most vulnerable—

Remember that fetal weight normally doubles in the last trimester of pregnancy, with 900 grams (about 2 pounds) of that gain occurring in the final three weeks. Thus, a baby born preterm (three or more weeks early; no longer called premature) is usually, but not always, LBW. In addition, some fetuses gain weight slowly throughout pregnancy and are small-

Mothers and Small Babies

Maternal or fetal illness might cause SGA, but maternal drug use is a more common cause. Every psychoactive drug slows fetal growth, with tobacco implicated in 25 percent of all low-

Another common reason for slow fetal growth as well as preterm birth is malnutrition. Women who begin pregnancy underweight, who eat poorly during pregnancy, or who gain less than 3 pounds (1.3 kilograms) per month in the last six months more often have underweight infants.

Unfortunately, many risk factors—

What About the Father?

The causes of low birthweight just mentioned rightly focus on the pregnant woman. However, fathers—

As already explained in Chapter 1, each person is embedded in a social network. Since the future mother’s behavior impacts the fetus, everyone who affects her also affects the fetus. She may be stressed because of her boss, her mother, her mother-

Not only fathers but also the entire social network and culture are crucial (Lewallen, 2011). This is most apparent in what is called the immigrant paradox. Many immigrants have difficulty getting education and well-

This paradox was first called the Hispanic paradox, because, although U.S. residents born in Mexico or South America average lower SES than people of Hispanic descent born in the United States, their newborns have fewer problems. The same discrepancy has now been demonstrated for immigrants from the Caribbean, Africa, Eastern Europe, and Asia. Why? The crucial factor may be fathers and grandmothers, who keep pregnant immigrant women drug-

Consequences of Low Birthweight

You have already read that life itself is uncertain for the smallest newborns. Ranking worse than most developed nations—

For survivors born very low birthweight, every developmental milestone—

Longitudinal research from many nations finds that children who were at the extremes of SGA or preterm have many neurological problems in middle childhood, including smaller brain volume, lower IQs, and behavioral difficulties (Clark et al., 2013; Hutchinson et al., 2013; van Soelen et al., 2010). Even in adulthood, risks persist: Adults who were LBW are more likely to develop diabetes and heart disease, partly because they are more often obese.

Longitudinal data provide both hope and caution. Remember that risk analysis gives probabilities, not certainties—

Comparing Nations

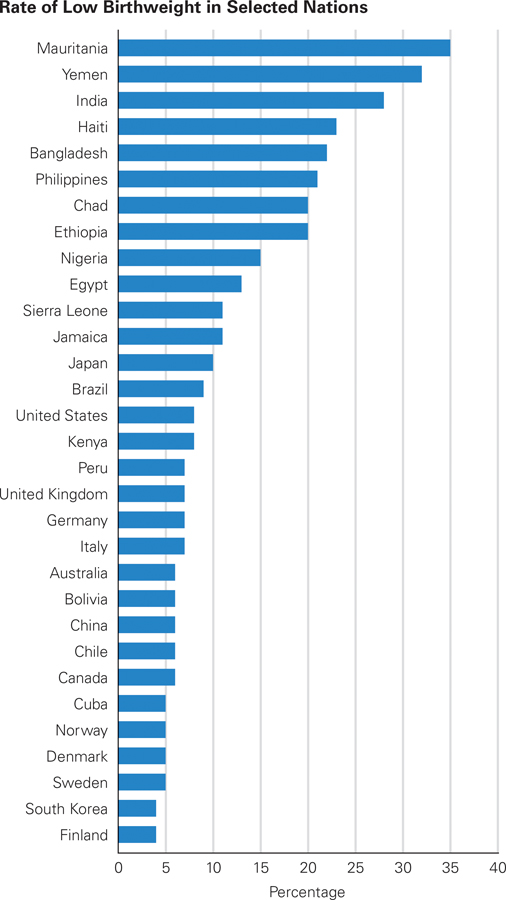

In some northern European nations, only 4 percent of newborns weigh under 2,500 grams; in several South Asian nations, including India, Pakistan, and the Philippines, more than 20 percent do. Worldwide, far fewer low-

Some nations, China and Bangladesh among them, have improved markedly. In 1970, an estimated half of Chinese newborns were LBW; recent estimates put that number at 6 percent (Chen et al., 2013). In 1990, half of newborns in Bangladesh were LBW (World Bank, 1994, p. 214); now the rate is 22 percent (UNICEF, 2014). In some nations, community health programs aid the growth of the fetus. That has an effect, according to a study provocatively titled Low birth weight outcomes: Why better in Cuba than Alabama? (Neggers & Crowe, 2013).

In some nations, notably in sub-

Getting Better Some public health experts consider the rate of low birthweight to be indicative of national health, since both are affected by the same causes. If that is true, the world is getting healthier, since the LBW world average was 28 percent in 2009 but 16 percent in 2012. When all nations are included, 47 report LBW at 6 percent or less (United States and United Kingdom are not among them).

Many scientists have developed hypotheses to explain the U.S. rates. One logical possibility is assisted reproduction, since ART often leads to low-

Added to the puzzle is the fact that several changes in maternal ethnicity, age, and health since 1990 should have decreased LBW, not increased it. For example, African Americans have LBW newborns much more often than the national average (almost 13.2 percent compared with 8 percent), and younger teenagers have smaller babies than do women in their 20s. However, since 1990 the birth rate among both groups has decreased markedly, so average LBW should decrease, not increase. Furthermore, maternal obesity and diabetes have increased since 1990; both lead to heavier babies. Nonetheless, more underweight babies are born.

Something must be amiss. One possibility is nutrition. Nations with many small newborns are also nations where hunger is prevalent. In both Chile and China, LBW fell as nutrition improved.

As for the United States, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (2014) reports an increase in the rate of food insecurity (measured by skipped meals, use of food stamps, and outright hunger) between the first 7 years of the twenty-

Another possibility is drug use. For example, the rate of smoking and drinking among high school girls reached a low in 1992, then increased, then decreased. Most U.S. women giving birth in the first decade of the twenty-

Watch Video: Low Birthweight in India, which discusses the causes of low birthweight among babies in India.

Another possible cause of LBW is pollution. Air pollution is decreasing in the United States. If pollution is the cause, fewer LBW babies will be born. On the other hand, many chemicals are more common in the maternal blood stream than they were. Looking at food, drug, pollution, and chemical trends in various nations will help developmentalists understand how to prevent LBW in the future.

SUMMING UP Low birthweight, either because of slow prenatal growth or preterm birth, increases vulnerability and may slow down development lifelong. Causes are many, from drug use to hunger, and vary markedly from nation to nation. The birth process itself can worsen the effects of any prenatal risk, with the smallest newborns at particular risk for early death or lifetime impairment. In general, low SES increases the risk for low birthweight, but some international data as well as the immigrant paradox suggest that it is not simply poverty that causes underweight newborns.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 4.18

What are the differences among LBW, VLBW, and ELBW?

Low birthweight (LBW) is defined as weight less than 2,500 grams (5 pounds, 8 ounces). LBW babies are further grouped into very low birthweight (VLBW), which is less than 1,500 grams (3 pounds, 5 ounces), and extremely low birthweight (ELBW), which is less than 1,000 grams (2 pounds, 3 ounces).Question 4.19

What are four reasons a baby might be born LBW?

Being born preterm, maternal or fetal illness, maternal psychoactive drug use, and maternal malnutrition can cause a baby to be born LBW.Question 4.20

What are the national and international trends in low birthweight?

In some northern European nations, only 4 percent of newborns weigh under 2,500 grams; in several South Asian nations, including India, Pakistan, and the Philippines, more than 20 percent do. Worldwide, far fewer low–birthweight babies are born than two decades ago; as a result, neonatal deaths have been reduced by one– third. Some nations, China and Bangladesh among them, have improved markedly. In 1970, an estimated half of Chinese newborns were LBW; recent estimates put that number at 6 percent. In 1990, half of newborns in Bangladesh were LBW; now the rate is 22 percent. Another nation with a troubling rate of LBW is the United States, where the rate fell throughout most of the twentieth century, reaching a low of 7 percent in 1990. But then it rose again, with the 2012 rate at 7.99 percent, ranging from under 6 percent in Alaska to over 12 percent in Mississippi. The U.S. rate is higher than that of virtually every other developed nation. Question 4.21

How might the father’s role be one reason for immigration paradox?

The causes of low birthweight rightly focus on the pregnant woman. However, fathers are often crucial. As an editorial in a journal for obstetricians explains: “Fathers' attitudes regarding the pregnancy, fathers' behaviors during the prenatal period, and the relationship between fathers and mothers . . . may indirectly influence risk for adverse birth outcomes.” Not only fathers but also the entire social network and culture are crucial. This is most apparent in what is called the immigrant paradox. Many immigrants have difficulty getting education and well–paid jobs; their socioeconomic status is low. Low SES correlates with low birthweight. Thus, newborns born to immigrants are expected to be underweight. But, paradoxically, they are generally healthier in every way, including birthweight, than newborns of U.S. born women of the same gene pool This paradox was first called the Hispanic paradox because, although U.S. residents born in Mexico or South America average lower SES than people of Hispanic descent born in the United States, their newborns have fewer problems. The same discrepancy has now been demonstrated for immigrants from the Caribbean, Africa, Eastern Europe, and Asia. The crucial factor may be fathers and grandmothers who keep pregnant immigrant women drug– free and healthy, counteracting the stress of poverty. Question 4.22

What is the prediction for the future of an ELBW newborn who survives?

When compared with newborns conceived at the same time but born later, low–birthweight (LBW) infants are older when they first smile, hold a bottle, walk, and communicate. As the months go by, cognitive difficulties as well as visual and hearing impairments may emerge. Survivors who were high– risk newborns tend to become infants and children who cry more, pay attention less, disobey, and experience language delays. Even in adulthood, some risks persist. Low– birthweight infants have higher rates of obesity, heart disease, and diabetes. The data provide hope as well as caution: Some LBW infants develop normally, overcoming their early problems if they receive excellent early care in the hospital and then at home.