Body Changes

In infancy, growth is so rapid and the consequences of neglect so severe that gains are closely monitored. Medical checkups, including measurement of height, weight, and head circumference, provide the first clues as to whether an infant is progressing as expected—

Body Size

Video: Physical Development in Infancy and Childhood offers a quick review of the physical changes that occur in a child’s first two years.

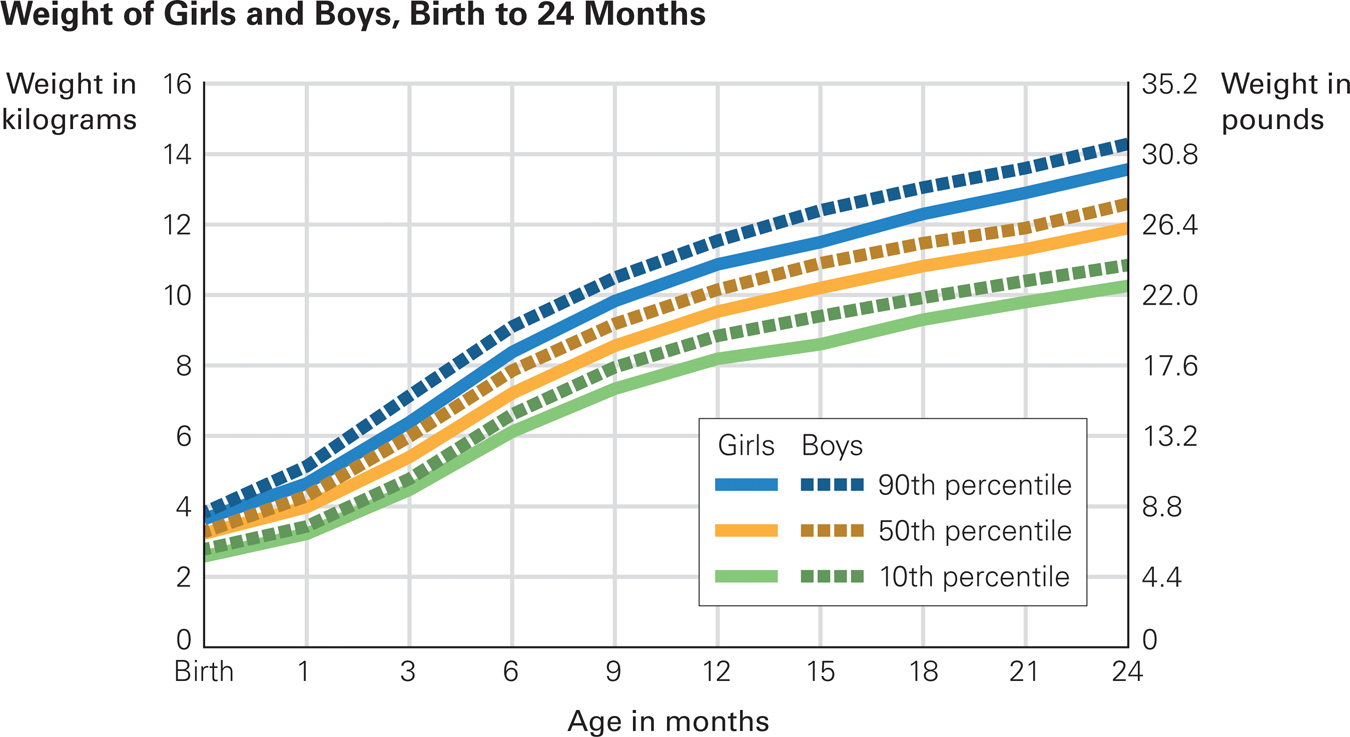

Newborns lose several ounces in the first three days and then gain an ounce a day for months. Birthweight typically doubles by 4 months and triples by a year. On average, a 7-

Physical growth then slows, but not by much. Most 24-

Eat and Sleep The rate of increasing weight in the first weeks of life makes it obvious why new babies need to be fed day and night.

At each well-

Thus, a 3-

For any baby, however, an early sign of trouble occurs when a percentile moves 20 percent or more, either up or down. If an average baby suddenly grows more slowly, that could be the first sign of a medical condition called failure to thrive. If weight gain is accelerated, as when a baby at the 30th percentile is at the 60th percentile a month later, that may signal later obesity.

A dramatic shift in percentile in either direction was once blamed solely on parents. For small babies, it was thought that parents made feeding stressful, leading to “nonorganic failure to thrive.” Now dozens of medical conditions have been discovered that cause failure to thrive. Thus, organic causes may impede growth. Pediatricians consider it “outmoded” to blame parents (Jaffe, 2011, p. 100).

Sleep

Throughout childhood, regular and ample sleep correlates with normal brain maturation, learning, emotional regulation, academic success, and psychological adjustment (Maski & Kothare, 2013). Lifelong, sleep deprivation can cause poor health, and vice versa. As with many health habits, sleep patterns begin in the first year.

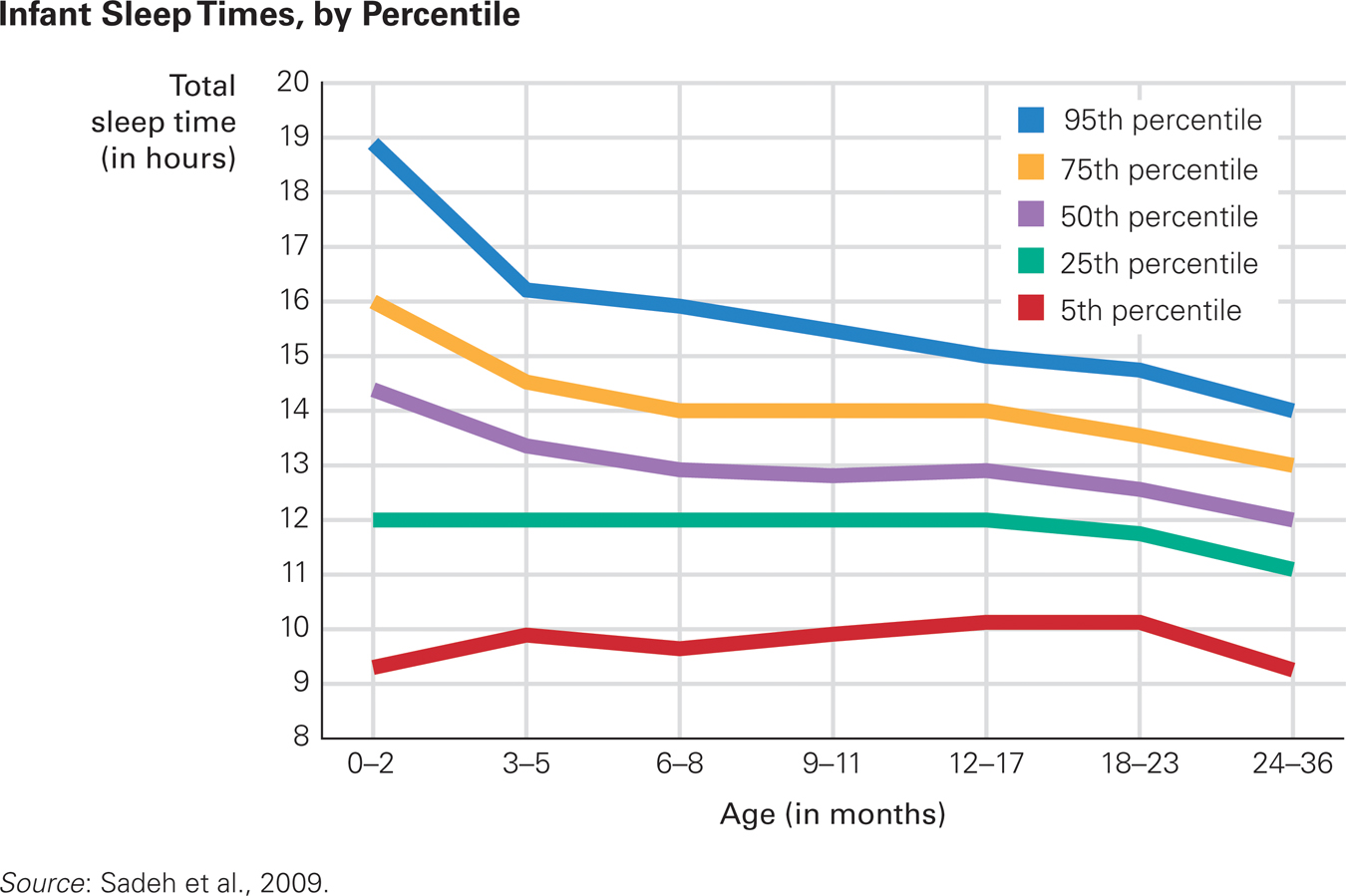

Newborns spend most of their time sleeping, about 15 to 17 hours a day. Hours of sleep decrease rapidly with maturity: The norm per day for the first 2 months is 14¼ hours; for the next 3 months, 13¼ hours; for 6 to 17 months, 12¾ hours. Remember that norms are simply averages. Among every 20 newborns in the United States, parents report that one sleeps only nine hours per day and one sleeps 19 hours (Sadeh et al., 2009) (see Figure 5.2).

Good Night, Moon Average sleep per 24-

Cultural differences are apparent. By age 2, the typical toddler in New Zealand sleeps 15 percent more than the typical Japanese one, 13.3 hours a day compared to 11.6 (Sadeh et al., 2010). Everywhere, full-

Infants also vary in how long they sleep at a stretch. If “sleeping through the night” means sleeping from midnight to 5 a.m., half of all babies sleep through the night at least once by 3 months, but if a night is from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., some 1-

Over the first months, the relative amount of time spent in each type or stage of sleep changes. Babies born preterm may always seem to be dozing. Full-

By about 3 months, all the various states of waking and sleeping become more evident. Thus, although newborns often seem half asleep, neither in deep sleep nor wide awake, by 3 months most babies have periods of alertness and periods of deep sleep (when noises do not rouse them).

Sleep varies not only because of biology (age and genes) but also because of caregiver actions. Babies who are fed cow’s milk and cereal sleep longer and more soundly—

Insufficient sleep may become a serious problem for parents as well as for infants, because “[p]arents are rarely well-

opposing perspectives

Where Should Babies Sleep?

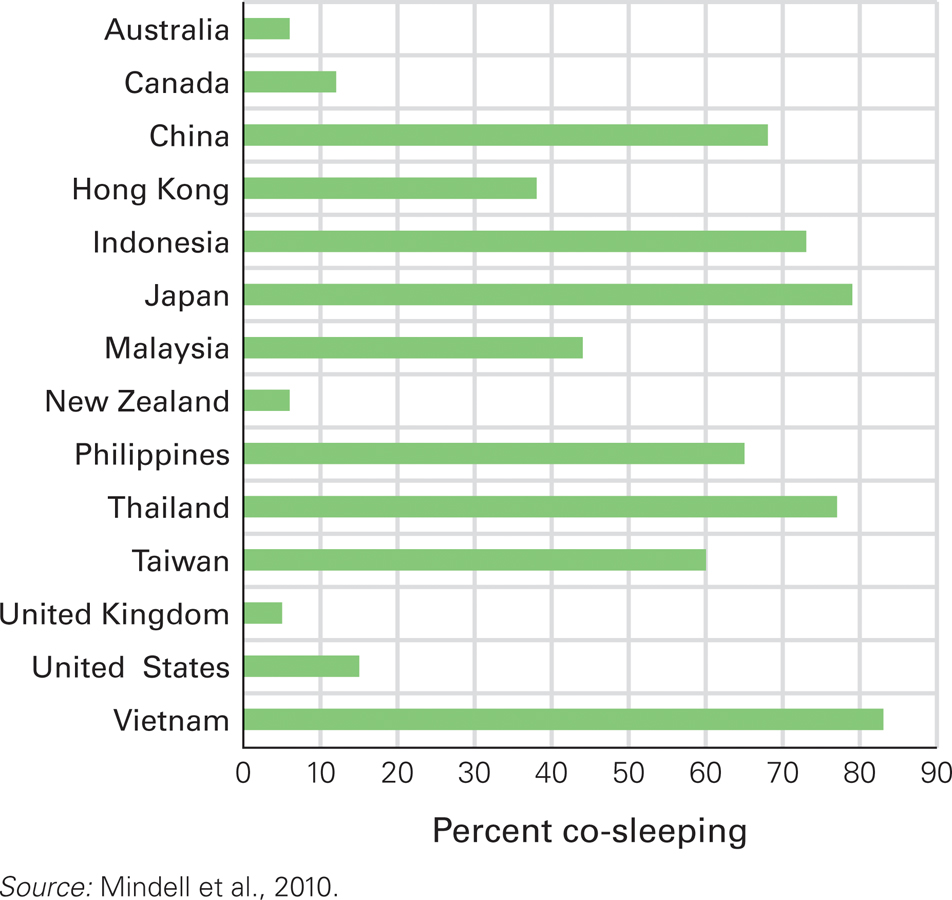

Traditionally, most middle-

Even today, at baby’s bedtime, Asian and African mothers worry more about separation, whereas European and North American mothers worry more about privacy. A survey found that parents act on these fears: The extremes were 82 percent of Vietnam babies co-

This difference in practice may seem related to income since low-

Awake at Night Why the disparity between Asian and non-

The argument for bed-

Yet the argument against bed-

Since many ethnic groups co-

One reason for opposite practices is that adults are affected by their own early experiences. This phenomenon is called ghosts in the nursery because new parents bring decades-

For example, compared with Israeli adults who, as infants, had slept near their parents, those who had slept communally with other infants (as sometimes occurred on kibbutzim) were more likely to interpret their own infants’ nighttime cries as distress, requiring comfort (Tikotzky et al., 2010). That is how a ghost affects current behavior: If parents think their crying babies are frightened, lonely, and distressed, they want to respond. Quick responses are easier with co-

But remember that infants learn from experience. If babies become accustomed to bed-

Developmentalists hesitate to declare either co-

An Internet study of more than 5,000 North American children under age 3 found that, according to their parents, sleep was a problem for 25 percent (Sadeh et al., 2009). Of course, parents are more troubled by their baby’s difficulty going to sleep, or staying asleep, than the baby is. This does not render sleep difficulties insignificant; overtired parents are less patient and responsive.

Parents will be frustrated if they expect their infant to conform to the parents’ sleep–

Especially for New Parents You are aware of cultural differences in sleeping practices, which raises a very practical issue: Should your newborn sleep in bed with you?

From the psychological and cultural perspectives, babies can sleep anywhere as long as the parents can hear them if they cry. The main consideration is safety: Infants should not sleep on a mattress that is too soft, nor beside an adult who is drunk or drugged. Otherwise, each family should decide for itself.

Parent reactions shape infant sleep patterns, which in turn affect the parents (Sadeh et al., 2010). Ideally, mutual adaptations allow everyone’s needs to be met, but, as the Opposing Perspectives feature explains, this is more controversial than it seems.

SUMMING UP Birthweight doubles, triples, and quadruples by 4 months, 12 months, and 24 months, respectively. Height increases by about a foot (about 30 centimeters) in the first two years. Such norms are useful as general guidelines, but personal percentile rankings over time are more telling. They indicate whether a particular infant’s brain and body are growing appropriately. With maturation, sleep becomes regular, dreaming becomes less common, and distinct sleep–

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 5.1

What specific facts indicate that infants grow rapidly in the first year?

Birthweight typically doubles by 4 months and triples by a year. On average, a 7–pound newborn will be 21 pounds at 12 months (9,525 grams, up from 3,400 grams at birth). Height increases, too. A typical baby grows 10 inches (24 centimeters) in a year. Question 5.2

Why are pediatricians not troubled when an infant is consistently small, say at the 20th percentile in height and weight?

At each well–baby checkup (monthly at first), growth is compared to the baby's previous numbers. Often, measurements are expressed as a percentile, from 0 to 100, that indicates where an individual ranks on a particular measure. Percentiles are often used for school achievement; here they are used to indicate how an infant's growth compares to other babies of the same age. Thus, a 3– month– old's weight at the 20th percentile means that 20 percent of 3– month– old babies weigh less and 80 percent weigh more. If the percentile were 60, then 60 percent weigh less and 40 percent weigh more. The fact that the first baby is a little smaller and the second a little bigger than average is not a problem, since humans vary on every dimension. Only one baby in 100 is exactly average at the 50th percentile. Question 5.3

How much do newborns usually sleep and dream?

Newborns spend most of their time sleeping, about 15 to 17 hours a day. Hours of sleep decrease rapidly with maturity. The norm per day for the first 2 months is 14¼ hours; for the next 3 months, 13¼ hours; for 6 to 17 months, 12¾ hours. However, norms are simply averages. Among every 20 newborns in the United States, parents report that one sleeps only nine hours per day and one sleeps 19 hours. Full–term newborns dream a lot; about half their sleep is REM sleep (rapid eye movement sleep), with flickering eyes and rapid brain waves. That indicates dreaming. REM sleep declines over the early weeks, as does “transitional sleep,” the dozing, half– awake stage. At 3 or 4 months, quiet sleep (also called slow– wave sleep) increases markedly. Question 5.4

How do sleep patterns change from birth to 18 months?

Hours of sleep decrease rapidly with maturity. The norm per day for the first two months is 14¼ hours; for the next three months, 13¼ hours; for six to 17 months, 12¾ hours.