Perceiving and Moving

You learned in Chapter 2 that Piaget called the first period of intelligence the sensorimotor stage, emphasizing that cognition develops from the senses and motor skills. The same concept—

The Senses

Every sense functions at birth. Newborns have open eyes, sensitive ears, and responsive noses, tongues, and skin. Indeed, very young babies use all their senses to attend to everything. For instance, in the first months of life, they smile at strangers and suck almost anything in their mouths.

Why are new infants not more discriminating? Because sensation precedes perception. Then perception leads to cognition. Thus, in order to learn, babies begin by responding to every sensation that might be significant; they will learn which sensations are meaningful.

Sensation occurs when a sensory system detects a stimulus, as when the inner ear reverberates with sound or the eye’s retina and pupil intercept light. Thus, sensations begin when an outer organ (eye, ear, nose, tongue, or skin) meets anything that can be seen, heard, smelled, tasted, or touched.

Genetic selection over more than 100,000 years affects all the senses. Humans cannot hear what mice hear, or see what bats see, or smell what puppies smell; humans do not need those sensory abilities. However, survival requires babies to respond to people, and newborns innately do so with every sense they have (Konner, 2010; Zeifman, 2013).

Perception occurs when the brain processes a sensation. This happens in the cortex, usually as the result of a message from one of the sensing organs, such as from the eye to the visual cortex. If a particular sensation occurs often, it connects with past experience, making a particular sight worth interpreting (M. E. Diamond, 2007).

Some sensations are beyond a baby’s comprehension at first. A newborn has no idea that the letters on a page might have significance, that Sister’s face should be distinguished from Brother’s, or that the smells of roses and garlic have different connotations. Perceptions require experience.

Infants’ brains are especially attuned to their own repeated social experiences. Thus, a newborn named Emily has no concept that Emily is her name, but she has the brain and auditory capacity to hear sounds in the usual speech range (not the high sounds that only dogs can hear) and an inborn preference for repeated patterns and human speech, so she attends to people saying her name. At about 4 months, when her auditory cortex is rapidly creating and pruning dendrites, the repeated word Emily is perceived as well as sensed, especially because that sound emanates from the people Emily has learned to love. Before 6 months, Emily may open her eyes and turn her head when her name is called. It will take many more months before she tries to say “Emmy” and still longer before she knows that Emily is indeed her name.

Thus, perception follows sensation, when sensory stimuli are interpreted in the brain. Then cognition follows perception, when people think about what they have perceived. (Later, cognition no longer depends on sensation: People imagine, fantasize, hypothesize.) The sequence from sensation to perception to cognition requires that an infant’s sense organs function. No wonder the parts of the cortex dedicated to hearing, seeing, and so on develop rapidly. Now some specifics.

Hearing

Especially for Nurses and Pediatricians The parents of a 6-

Urge the parents to begin learning sign language and investigate the possibility of cochlear implants. Babbling has a biological basis and begins at a specified time, in deaf as well as hearing babies. If their infant can hear, sign language does no harm. If the child is deaf, however, noncommunication may be destructive.

The sense of hearing develops during the last trimester of pregnancy and is already quite acute at birth, when certain sounds trigger reflexes, even without conscious perception. Sudden noises startle newborns, making them cry. Familiar, rhythmic sounds such as a heartbeat are soothing: That is one reason kangaroo care reduces newborn stress, because the infant’s ear rests on the mother’s chest. (Developmental Link: Kangaroo care is explained in Chapter 4.)

A newborn’s hearing can be checked with advanced equipment; this is routinely done at most hospitals in North America and Europe, since early remediation benefits deaf infants. Screening is needed later as well because some infants develop hearing losses in the early months (Harlor & Bower, 2009). Normally, even in the first days of life, infants turn their heads at a sound. Soon they can pinpoint the source of the noise.

Because of maturation of the language areas of the cortex, even 4-

Infants become accustomed to their native language, such as which syllable is stressed (dialects vary), if changing inflection matters (as in Chinese), whether certain sound combinations are repeated, and so on. All this is based on very careful listening to human speech, including speech not directed toward them with words they do not yet understand (Buttelmann et al., 2013).

Seeing

By contrast, vision is immature at birth. Although in mid-

Almost immediately, experience combines with maturation of the visual cortex to improve the ability to see shapes and notice details. Vision improves so rapidly that researchers are hard-

By 2 months, infants not only stare at faces, but also, with perception, smile. (Smiling can occur earlier but not because of perception.) As perception builds, visual scanning improves. Thus, 3-

Because binocular vision (coordinating both eyes to see one image) is impossible in the womb (nothing is far enough away), many newborns seem to use their two eyes independently, momentarily appearing wall-

This ability aids in the development of depth perception, which has been demonstrated in 3-

Tasting and Smelling

As with vision and hearing, smell and taste function at birth and rapidly adapt to the social world. Infants learn to appreciate what their mothers eat, first through breast milk and then through smells and spoonfuls of the family dinner.

Some herbs and plants contain natural substances that are medicinal. The foods of a particular culture may aid survival: For example, bitter foods provide some defense against malaria, hot spices help preserve food and thus work against food poisoning, and so on (Krebs, 2009). Thus, for 1-

Families who eat foods that protected their community pass on those preferences to their children throughout childhood. Taste preferences endure when a person migrates to another culture or when historical circumstances change so that a particular food that was once protective is no longer so. Indeed, one reason for the obesity epidemic is that, when starvation was a threat, families sought high-

Adaptation also occurs for the sense of smell. When breast-

As babies learn to recognize each person’s scent, they prefer to sleep next to their caregivers, and they nuzzle into their caregivers’ chests—

Touch and Pain

The sense of touch is acute in infants. Wrapping, rubbing, massaging, and cradling are each soothing to many new babies. Even when their eyes are closed, some infants stop crying and visibly relax when held securely by their caregivers. The newborn’s ability to be comforted by touch is tested in the Brazelton NBAS, described in Chapter 4. In the first year of life, their heart rate slows and babies relax when stroked gently and rhythmically on the arm (Fairhurst et al., 2014).

Pain and temperature are not among the traditional five senses, but they are often connected to touch. Some babies cry when being changed, distressed at the sudden coldness on their skin. Some touches are unpleasant—

Scientists are not certain about infant pain. Some experiences that are painful to adults (circumcision, setting of a broken bone) are much less so to newborns, although that does not mean that newborns never feel pain (Reavey et al., 2014). For many newborn medical procedures, from a pinprick to minor surgery, a taste of sugar right before the event is an anesthetic. An empirical study conducted with an experimental group and a control group found that newborns typically cry lustily when their heel is pricked (to get a blood sample, routine after birth) but not if they have had a drop of sucrose beforehand (Harrison et al., 2010).

Some people imagine that the fetus feels pain; others say that the sense of pain does not mature until months after birth. Many young infants cry inconsolably, at times; digestive pain is the usual explanation. Often, infants fuss before their first tooth erupts: Teething is said to be painful. However, these explanations are unproven; infant crying may not indicate pain, and absence of crying does not necessarily mean absence of pain (true for adults, too).

Physiological measures, including stress hormones, erratic heartbeats, and rapid brain waves, are studied to assess pain in preterm infants, who typically undergo many procedures that would be painful to an adult (Holsti et al., 2011). Infants’ brains are immature: We cannot assume that they do, or do not, feel pain, or feel it in the way that we do.

Motor Skills

The most dramatic motor skill (any movement ability) is independent walking, which explains why I worried when Bethany did not take a step (as described in the introduction to this chapter). All the basic motor skills, from the newborn’s head-

The first evidence of motor skills is in the reflexes, explained in Chapter 4. Although the definition of reflexes implies that they are automatic, their strength and duration vary from one baby to another. Many newborn reflexes disappear by 3 months, but some morph into more advanced motor skills.

Caregiving and culture matter. Reflexes become skills if they are practiced and encouraged. As you saw in the chapter’s beginning, Mrs. Todd set the foundation for my fourth child’s walking when Sarah was only a few months old. Similarly, some very young babies can swim—

Gross Motor Skills

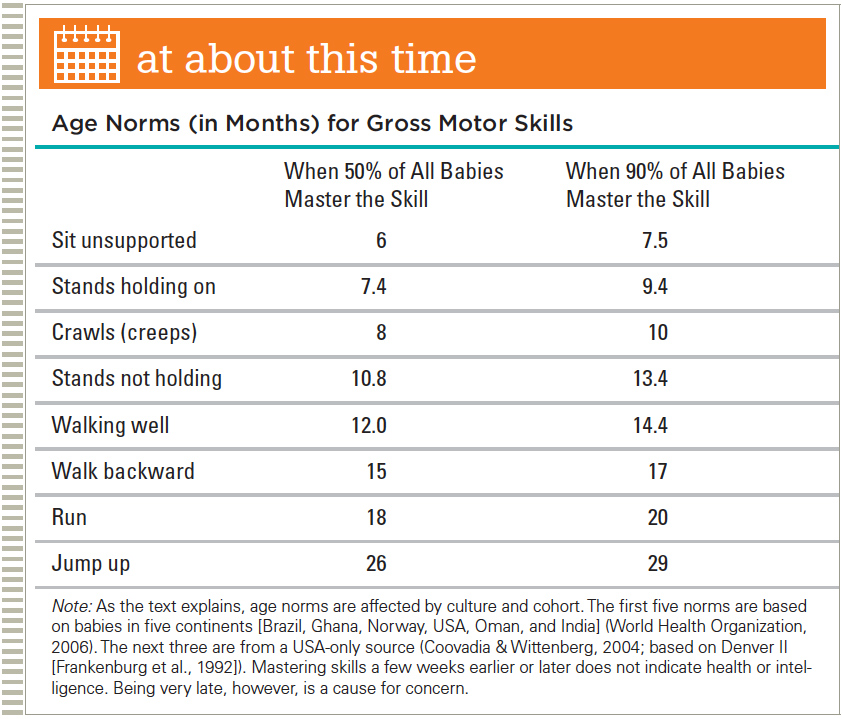

Deliberate actions that coordinate many parts of the body, producing large movements, are called gross motor skills. These skills emerge directly from reflexes and proceed in a cephalocaudal (head-

Sitting develops gradually; it requires developing the muscles to steady the top half of the body. By 3 months, most babies can sit propped up in a lap. By 6 months, they can usually sit unsupported. Babies never propped up (as in some institutions for abandoned babies) sit much later.

Question 5.11

OBSERVATION QUIZ Which of these skills has the greatest variation in age of acquisition? Why?

Jumping up, with a three–

Crawling is another example of the head-

Usually by 5 months, infants add their legs to this effort, inching forward (or backward) on their bellies. Exactly when this occurs depends partly on how much “tummy time” the infant has had to develop the muscles, and that, of course, is affected by the caregiver’s culture (Zachry & Kitzmann, 2011).

Between 8 and 10 months after birth, most infants can lift their midsections and crawl (or creep, as the British call it) on “all fours,” coordinating the movements of their hands and knees. Crawling depends on experience as well as maturation. Some normal babies never do it, especially if the floor is cold, hot, or rough, or if they have always lain on their backs (Pin et al., 2007). It is not true that babies must crawl to develop normally.

All babies find some way to move before they can walk (inching, bear-

The dynamic system underlying every motor skill has three interacting elements: strength, maturation, and practice. We illustrate these three here with walking.

Muscle strength. Newborns with skinny legs and 3-

month- olds buoyed by water make stepping movements, but 6- month- olds on dry land do not; their legs are too chubby for their underdeveloped muscles. As they gain strength, they stand and then walk. Brain maturation. The first leg movements—

kicking (alternating legs at birth and then both legs together or one leg repeatedly at about 3 months)—occur without much thought. As the brain matures, deliberate leg action becomes possible. Practice. Unbalanced, wide-

legged, short strides become a steady, smooth gait.

This last item, practice, is powerfully affected by caregiving before the first independent step. Some adults spend hours helping infants walk (holding their hands or the back of their shirts) or providing walkers (dangerous if not supervised).

Once toddlers are able to walk by themselves, they practice obsessively, barefoot or not, at home or in stores, on sidewalks or streets, on lawns or in mud. They fall often, but that does not stop them; “they average between 500 and 1,500 walking steps per hour so that by the end of each day, they have taken 9,000 walking steps and traveled the length of 29 football fields” (Adolph et al., 2003, p. 494).

Fine Motor Skills

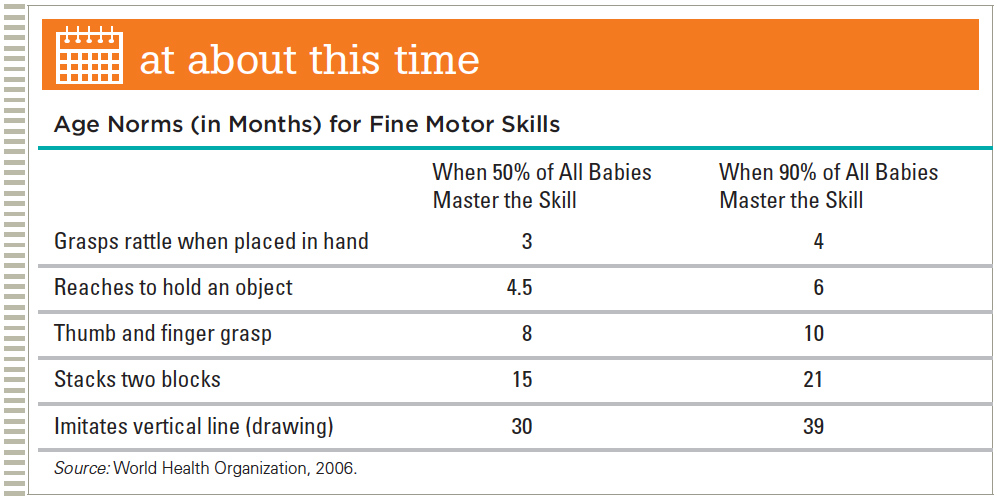

Small body movements are called fine motor skills. The most valued fine motor skills are finger movements, enabling humans to write, draw, type, tie, and so on. Movements of the tongue, jaw, lips, and toes are fine movements, too.

Video: Fine Motor Skills in Infancy and ToddlerhoodAMI PARIKH/SHUTTERSTOCK

Actually, mouth skills precede finger skills by many months (newborns can suck; chewing precedes drawing by a year or more). Since every culture encourages finger dexterity, children practice finger movements, and adults teach how to use spoons, or chopsticks, or markers.

By contrast, mouth skills such as spitting or biting are not praised. (Only other children admire blowing bubbles with gum.) Eventually, most children try to whistle, an advanced skill that some adults have not mastered. One mouth skill, pronunciation, develops gradually without special encouragement, although some older children and bilingual adults need focused practice to say difficult sounds.

Regarding hand skills, newborns have a strong reflexive grasp but lack control. During their first 2 months, babies excitedly stare and wave their arms at objects dangling within reach. By 3 months, they can usually touch such objects, but because of limited eye–

By 4 months, infants sometimes grab, but their timing is off: They close their hands too early or too late. Finally by 6 months, with a concentrated, deliberate stare, most babies can reach, grab, and grasp almost any object that is of the right size. Some can even transfer an object from one hand to the other. Almost all can hold a bottle, shake a rattle, and yank a sister’s braids.

Toward the end of the first year and throughout the second, finger skills improve as babies master the pincer movement (using thumb and forefinger to pick up tiny objects). They can feed themselves first with hands, then fingers, then utensils (Ho, 2010). (See At About This Time.)

As with gross motor skills, fine motor skills are shaped by culture and opportunity. For example, when given “sticky mittens” (with Velcro) that allow grabbing, infants master hand skills sooner than usual. Their perception advances as well (Libertus & Needham, 2010; Soska et al., 2010). More generally, all senses and motor skills expand the baby’s cognitive awareness, with practice advancing both skill and cognition (Leonard & Hill, 2014).

In the second year, grasping becomes more selective, as experience sculpts the brain. Toddlers learn when not to pull at a sister’s braids or an adult’s earrings or glasses. (Wise adults remove accessories before holding a baby.)

Dynamic Sensory-Motor Systems

Young human infants are, physiologically, an unusual combination of motor ineptness (they cannot walk for many months), sensory acuteness (all senses function at birth), and curiosity (Konner, 2010). What a contrast to kittens, for instance, who are born deaf, with eyes sealed shut, and who stay beside their mother although they can walk.

Human newborns listen and look from day 1, eager to practice every skill as soon as possible. An amusing example is rolling over. At about 3 months, infants can roll over from their stomachs to their backs, but not vice versa because their arms are no help when they are flat on their backs. Once they can roll from stomach to back, many babies do so and then fuss, turtle-

The most important experiences are perceived with interacting senses and skills, in dynamic systems. Breast milk, for instance, is a mild sedative, so the newborn literally feels happier at Mother’s breast, connecting that pleasure with taste, touch, smell, and sight. But in order for all those joys to occur, the infant must actively suck at the nipple (an inborn motor skill, which becomes more efficient with practice).

Because of brain immaturity, cross-

Infants respond to motion as well as to sights and sounds. Many new parents soothe their baby’s distress by rocking, carrying, or even driving (with the baby in a safety seat) while crooning a lullaby; here again, infant comfort is dynamically connected with social interaction. Massage is especially calming when infants realize that the touch comes from a familiar caregiver who simultaneously provides auditory and visual stimulation. Even vacuuming the carpet with the baby in a sling may quiet a fussy baby because steady noise, changing sights, and carrying combine to soothe distress.

By 6 months, babies have learned to coordinate senses and skills, expecting another person’s lip movements to synchronize with speech, for instance (Lewkowicz, 2010). Grabbing, crawling, and walking are dynamic systems that allow exploration, which in turn fosters cognition (Leonard & Hill, 2014).

The time at which walking occurs is a better predictor than age of a child’s verbal ability, perhaps because walking children elicit more language from caregivers than crawling ones do (Walle & Campos, 2014). No wonder Piaget linked cognitive and physical development, as Chapter 6 describes.

Cultural Variations

Culture affects every infant move. All healthy infants develop skills in the same sequence, but the age of acquisition varies because each culture encourages certain kinds of practice. When U. S. infants are grouped by ethnicity, generally African American babies are ahead of Latino babies when it comes to walking. In turn, Latino babies are ahead of those of European descent.

Internationally, the earliest walkers are in Africa, where many well-

What accounts for normal variation? The power of genes is suggested not only by ethnic differences but also by identical twins, who begin to walk on the same day more often than fraternal twins do. Striking individual differences are apparent in infants’ strategies, effort, and concentration in mastering motor skills, again suggesting something inborn (Thelen & Corbetta, 2002).

But much more than genes contribute to variations, as the example that opened this chapter shows. Cultural patterns affect acquisition of every sensory and motor skill, with the important of practice evident in hundreds of studies on infant walking (Adolph and Robinson, 2013).

Early reflexes may not fade if culture and conditions allow extensive practice. This has been demonstrated with legs (the stepping reflex), hands (the grasping reflex), and crawling (the swimming reflex). Senses and motor skills are part of a complex and dynamic system in which practice counts (Thelen & Corbetta, 2002). Nutrition makes a difference as well: Both malnourished and overweight children are slower to develop motor skills.

Cross-

The people of Bali, Indonesia, never let their infants crawl, because babies are considered divine and crawling is for animals (Diener, 2000). Similar reasoning appeared in colonial America, where “standing stools” were designed for children so they could strengthen their legs without sitting or crawling (Calvert, 2003).

By contrast, traditionally the Beng people of the Ivory Coast are proud when their babies start to crawl but do not let them walk until at least 1 year. Although the Beng do not recognize the connection, one reason for this prohibition may be birth control: Beng mothers do not resume sexual relations until their baby takes a first step (Gottlieb, 2000). Another culture with late walkers are the Ache, who live in the jungles of Paraguay, where poisonous snakes could kill a young child. The Ache hold their babies near them day and night; the children first walk on their own at about two years (Adolph & Robinson, 2013).

Although variation in the timing of the development of motor skills is normal, slow development relative to the norm within an infant’s culture suggests that attention should be paid: Early visual, auditory, and motor difficulties are much easier to remedy than the same problems discovered later in childhood.

Remember the dynamic systems of senses and motor skills: If one aspect of the system lags behind, the other parts may be affected as well. On the other hand, early walkers are thrilled to have within reach dozens of objects they were unable to explore before—

SUMMING UP All the senses function at birth, with hearing the most acute sense and vision the least developed. Every sense allows perception to develop and furthers social understanding. Caregivers are soon recognized by sight, touch, smell, and voice. Using both eyes in coordination to understand depth takes several weeks. Pain perception seems less acute for newborns than for older children and adults.

Gross motor skills follow a genetic timetable for maturation; they are also affected by practice and experience. Caregivers and cultures that encourage movement of the infant body in the first months of life are likely to have babies who walk before a year. Fine motor skills also develop with time and experience, combining with the senses as part of dynamic systems. Mouth skills precede finger skills, although both are immature in the early months and years. All the skills are practiced relentlessly as soon as possible, advancing learning and thinking.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 5.12

What is the relationship between perception and sensation?

Sensation is when a sensory system detects a stimulus. It precedes perception, which is the processing of a sensation.Question 5.13

What particular sounds and patterns do infants pay attention to?

Because of maturation of the language areas of the cortex, even 4–month– old infants attend to voices, developing expectations of the rhythm, segmentation, and cadence of spoken words long before comprehension. Soon, sensitive hearing combines with the maturing brain to distinguish patterns of sounds and syllables. Infants also become accustomed to their native language, such as which syllable is stressed (dialects vary), if changing inflection matters (as in Chinese), whether certain sound combinations are repeated, and so on. All this is based on very careful listening to human speech, including speech not directed toward them with words they do not yet understand. Question 5.14

How does an infant’s vision change over the first year?

Newborns are legally blind. Almost immediately, experience combines with maturation of the visual cortex to improve the ability to see shapes and then notice details. By 2 months, infants not only stare at faces but also, after perception and then cognition, smile. As perception builds, visual scanning improves. Thus, 3–month– old babies look closely at the eyes and mouth of a person, smiling more at smiling faces than at angry or expressionless ones. Binocular vision also develops between 2 and 4 months. Question 5.15

What is universal and what is cultural in the development of gross motor skills in infancy?

Universally, gross motor skills emerge directly from reflexes and proceed in a cephalocaudal (head–down) and proximodistal (center– out) direction. Infants first control their heads, lifting them up to look around. Then they control their upper bodies, their arms, and finally their legs and feet. Sitting develops gradually; it requires developing the muscles to steady the top half of the body. By 3 months, most babies can sit propped up in a lap. By 6 months, they can usually sit unsupported. Crawling is another example of the head– down and center– out direction of skill mastery. When placed on their stomachs, many newborns reflexively try to lift their heads and move their arms as if they were swimming. As they gain muscle strength, infants wiggle, attempting to move forward by pushing their arms, shoulders, and upper bodies against whatever surface they are lying on. Between 8 and 10 months after birth, most infants can lift their midsections and crawl on “all fours,” coordinating the movements of their hands and knees. All babies find some way to move before they can walk.

Despite universal trends in gross motor development, practice is powerfully affected by caregiving before the first independent step. Some adults spend hours helping infants walk (holding their hands or the back of their shirts) or providing walkers.Question 5.16

Why do infants develop fine motor skills using their fingers later than gross motor skills?

Many gross motor skills require less precision than fine motor skills, such as use of the fingers. In addition, gross motor development is often related to fine motor development.

Regarding hand skills, newborns have a strong reflexive grasp but lack control. During their first 2 months, babies excitedly stare and wave their arms at objects dangling within reach. By 3 months, they can usually touch such objects, but because of limited eye–hand coordination, they cannot yet grab and hold on unless an object is placed in their hands. By 4 months, infants sometimes grab, but their timing is off: They close their hands too early or too late. Finally by 6 months, with a concentrated, deliberate stare, most babies can reach, grab, and grasp almost any object that is of the right size. Some can even transfer an object from one hand to the other. Almost all can hold a bottle, shake a rattle, and yank a sister's braids. Toward the end of the first year and throughout the second, finger skills improve as babies master the pincer movement (using thumb and forefinger to pick up tiny objects). They can feed themselves first with hands, then fingers, then utensils.