Surviving in Good Health

Although precise worldwide statistics are unavailable, the United Nations estimates that more than 8 billion children were born between 1950 and 2015. Almost a billion of them died before age 5.

Although most of those 1 billion deaths could have been prevented, far more would have died without recent public health measures. In 1950 1 young child in 5 died, but only about 1 child in 20 is projected to die in 2014 (United Nations, 2015). In earlier centuries, more than half of all newborns died in infancy. Those are official statistics; probably millions more died without being counted.

Better Days Ahead

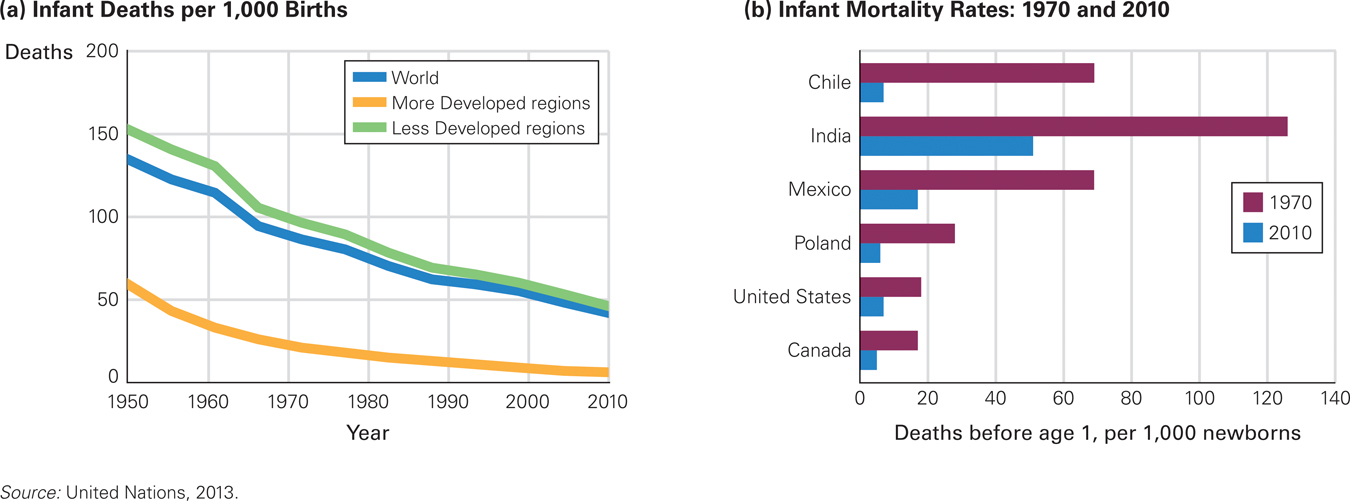

In the twenty-

More Babies Are Surviving Improvements in public health–

The world death rate in the first five years of life has dropped about 2 percent per year since 1990, (Rajaratnam et al., 2010) with the rate in developed nations less than 1 in 1,000, and in least developed nations about 1 in 200. Public health measures (clean water, nourishing food, immunization) deserve most of the credit.

As children survive, parents focus more effort and income on each child, having fewer children overall. That advances the national economy, which allows for better schools and health care. Infant survival and maternal education are the two main reasons the world’s fertility rate in 2010 was half the 1950 rate. This is found in data from numerous nations, especially developing ones, where educated women have far fewer children than those who are uneducated (de la Croix, 2013).

If there were enough public health professionals, the current newborn and child death rate could be cut in half again. Public health measures help parents as well as children, via better food distribution, less violence, more education, cleaner water, and more widespread immunization (Farahani et al., 2009).

a case to study

Scientist at Work

Susan Beal, a young scientist with four children, studied SIDS deaths in Australia for years, responding to phone calls, often at 5 or 6 a.m., that another baby had died. At first she felt embarrassed to question the parents, sometimes arriving before the police or the coroner. But parents were grateful to know that someone was trying to understand the puzzle that had just killed their infant. She realized that parents tended to blame themselves and each other, so she sought to get them talk to each other, as she reassured them that scientists shared their bewilderment. (Click on the video above to watch a short interview with Susan Beal.)

As a scientist, she noted dozens of circumstances at each death. Some things did not matter (such as birth order), others increased the risk (maternal smoking and lambskin blankets). A breakthrough came when Beal noticed an ethnic variation: Australian babies of Chinese descent died of SIDS far less often than did those of European descent. Genetic? Most experts thought so. But Beal noticed that almost all SIDS babies were sleeping on their stomachs, contrary to the Chinese custom of placing infants on their backs to sleep. She developed a new hypothesis: Sleeping position mattered.

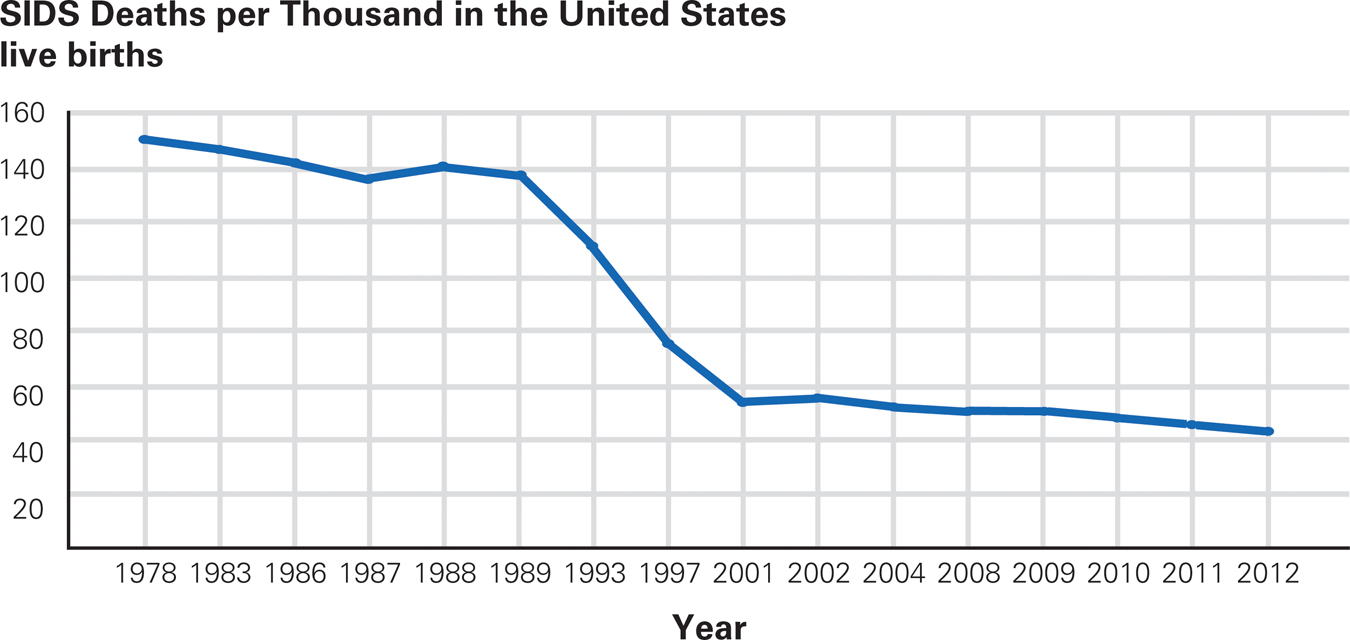

Alive Today As more parents learn that a baby should be on his or her “back to sleep,” the SIDS rate continues to decrease. Other factors are also responsible for the decline—

To test her hypothesis, Beal convinced a large group of non-

Replication and application spread. By 1994, a “Back to Sleep” campaign in nation after nation cut the SIDS rate dramatically (Kinney & Thach, 2009; Mitchell, 2009). In the United States in 1984 SIDS killed 5,245 babies; in 1996, that number was down to 3,050; in 2011 it was 1,910 (see Figure 5.8). Such results indicate that, in the United States alone, about 40,000 children and young adults are alive today who would be dead if they had been born before 1990. The campaign has been so successful that physical therapists report that babies now crawl later than they used to; they therefore advocate tummy time—putting awake infants on their stomachs to develop their muscles (Zachry & Kitzmann, 2011).

Stomach-

That does not surprise Susan Beal, who quickly realized that SIDS victims are found in many kinds of households, rich and poor, native-

Considering Culture

Often cultural variations are noted in infant care. There are many ways to care for a baby, with all the experience-

Sometimes, however, one mode of infant care is much better than another, and here a cross-

Every year until the mid-

Immunization

Immunization primes the body’s immune system to resist a particular disease. Immunization (often via vaccination) may have had “a greater impact on human mortality reduction and population growth than any other public health intervention besides clean water” (J. P. Baker, 2000, p. 199). Within the past 50 years, immunization eliminated smallpox and dramatically reduced chickenpox, flu, measles, mumps, pneumonia, polio, rotavirus, tetanus, and whooping cough. Now scientists seek to immunize against HIV/AIDS, malaria, Ebola, and other viral diseases.

Immunization protects not only from temporary sickness but also from complications, including deafness, blindness, sterility, and meningitis. Sometimes the damage from illness is not apparent until decades later. Having mumps in childhood, for instance, can cause sterility and doubles the risk of schizophrenia in adulthood (Dalman et al., 2008).

Some people cannot be safely immunized, including the following:

Embryos, who may be born blind, deaf, and brain-

damaged if their pregnant mother contracts rubella (German measles) Newborns, who may die from a disease that is mild in older children

People with impaired immune systems (HIV-

positive, aged, or undergoing chemotherapy), who can become deathly ill

Fortunately, each vaccinated child stops transmission of the disease and thus protects others, a phenomenon called herd immunity (mentioned in Chapter 1). Although specifics vary by disease, usually if 90 percent of the people in a community (a herd) are immunized, the disease does not spread. Without herd immunity, some community members die of a “childhood” disease.

Everywhere parents can refuse to vaccinate their children for medical reasons, but in 19 states of the United States, parents are able to opt out of vaccination because of “personal belief” (Blad, 2014). In Colorado, for instance, 15 percent of all kindergartners have never been immunized against measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, tetanus, or whooping cough. That is below herd immunity, and an epidemic could occur—

Problems with Immunization

Especially for Nurses and Pediatricians A mother refuses to have her baby immunized because she wants to prevent side effects. She wants your signature for a religious exemption, which in some jurisdictions allows the mother to refuse vaccination. What should you do?

It is difficult to convince people that their method of child rearing is wrong, although you should try. In this case, listen respectfully and then describe specific instances of serious illness or death from a childhood disease. Suggest that the mother ask her grandparents if they knew anyone who had polio, tuberculosis, or tetanus (they probably did). If you cannot convince this mother, do not despair: Vaccination of 95 percent of toddlers helps protect the other 5 percent. If the mother has genuine religious reasons, talk to her clergy adviser.

Infants may react to immunization by being irritable or even feverish for a day or so, to the distress of their parents. However, parents do not notice if their child does not get polio, measles, or so on. Before the varicella (chicken pox) vaccine, more than 100 people in the United States died each year from that disease, and 1 million were itchy and feverish for a week. Now almost no one dies of varicella, and far fewer get chicken pox.

Many parents are concerned about the potential side effects of vaccines. Whenever something seems to go amiss with vaccination, the media broadcast it, which frightens parents. This has occurred particularly as rates of autism have risen. (Developmental Link: The link between fear of immunization and increased rates of autism is discussed in A View from Science in Chapter 1.) As a result, the rate of missed vaccinations in the United States has been rising over the past decade. This horrifies public health workers, who, taking a longitudinal and society-

Video: Nutritional Needs of Infants and Children: Breast Feeding Promotion shows UNICEF’s efforts to educate women on the benefits of breastfeeding.

Concerns about safety are greatest for newer vaccines, including the annual flu shot. Pregnant women and young children are particularly likely to be seriously affected by flu, which has led the United States Centers for Disease Control to recommend vaccination. However, most pregnant women and about 30 percent of parents do not follow that recommendation (MMWR, March 7, 2014).

In 2012, two states, Connecticut and New Jersey, required flu vaccination for all 6-

Nutrition

As already explained, infant mortality worldwide has plummeted in recent years for several reasons: fewer sudden infant deaths, advances in prenatal and newborn care, and, as you just read, immunization. One more measure is making a huge difference: better nutrition.

Breast Is Best

Ideally, nutrition starts with colostrum, a thick, high-

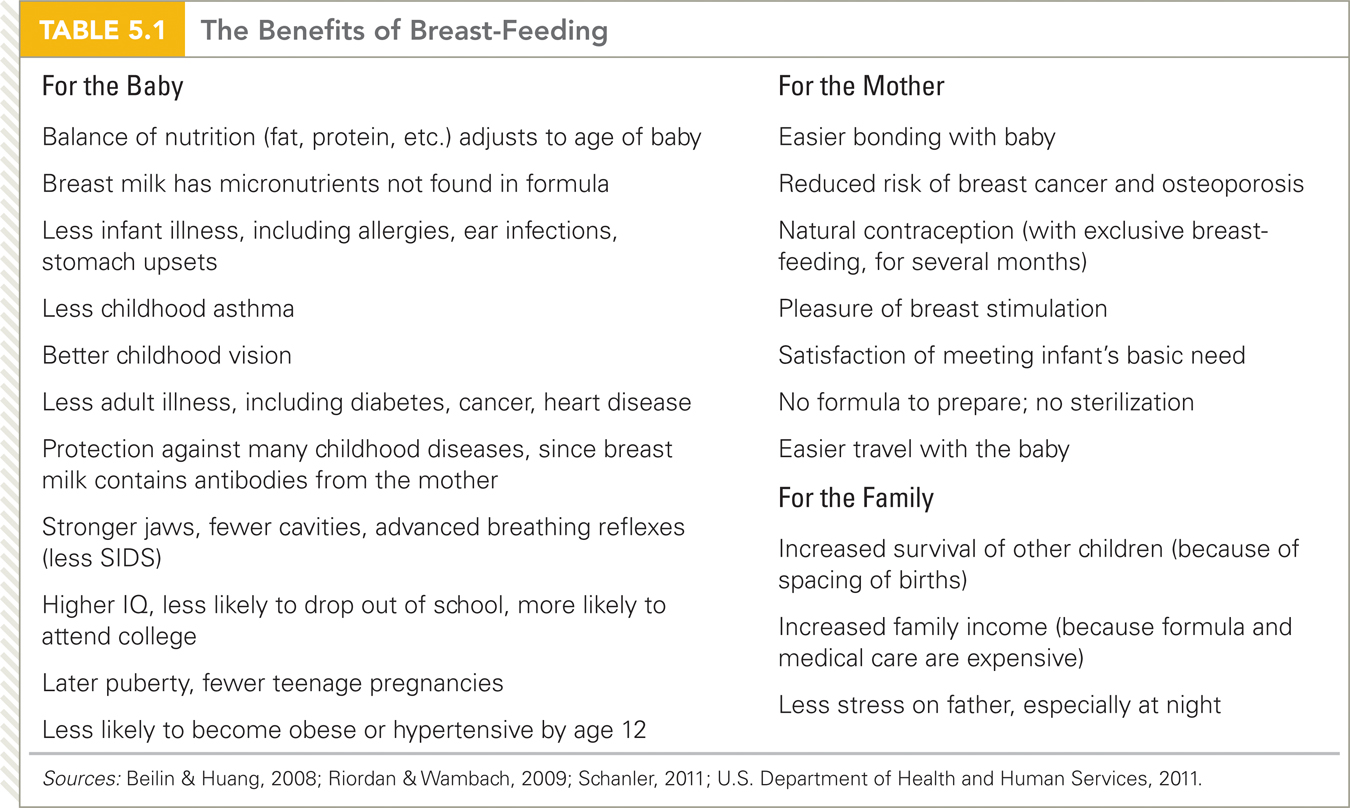

Compared with formula based on cow’s milk, human milk is sterile, always at body temperature, and rich in many essential nutrients for brain and body (Wambach & Riordan, 2014; Drover et al., 2009). Babies who are exclusively breast-

Breast-

The specific fats and sugars in breast milk make it more digestible and better for the brain than any substitute (Drover et al., 2009; Wambach & Riordan, 2014). The composition of breast milk adjusts to the age of the baby, with milk for premature babies distinct from that for older infants. Quantity increases to meet the demand: Twins and even triplets can be exclusively breast-

Formula is preferable only in unusual cases, such as when the mother is HIV-

Doctors worldwide recommend breast-

Do You Believe It?

This table lists so many advantages that some skepticism seems warranted. However, every item on this list arises from research that considers confounding factors, such as the mother’s health and education. It may be that breast milk is truly a miracle food.

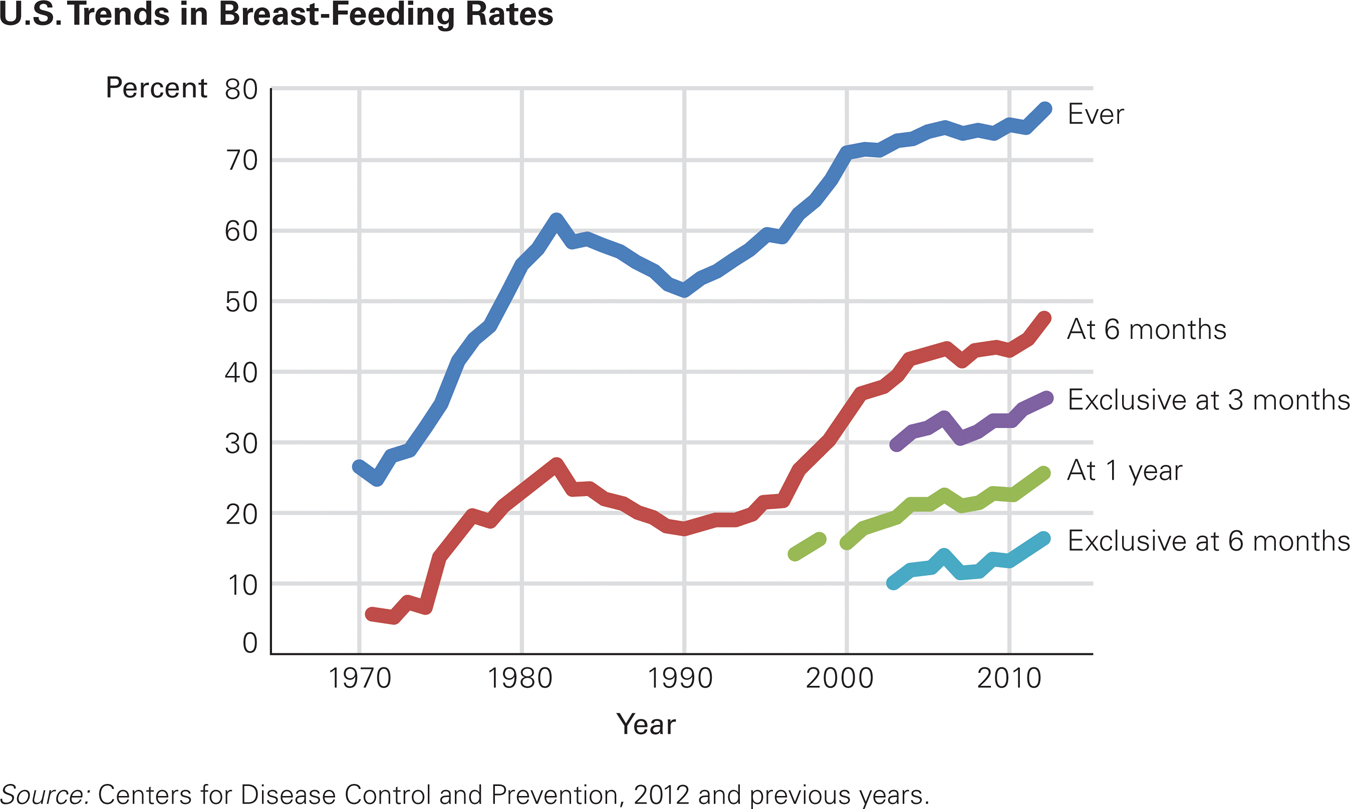

A Smart Choice In 1970, educated women were taught that formula was the smart, modern way to provide nutrition—

Breast-

Encouragement of breast-

Malnutrition

Protein-

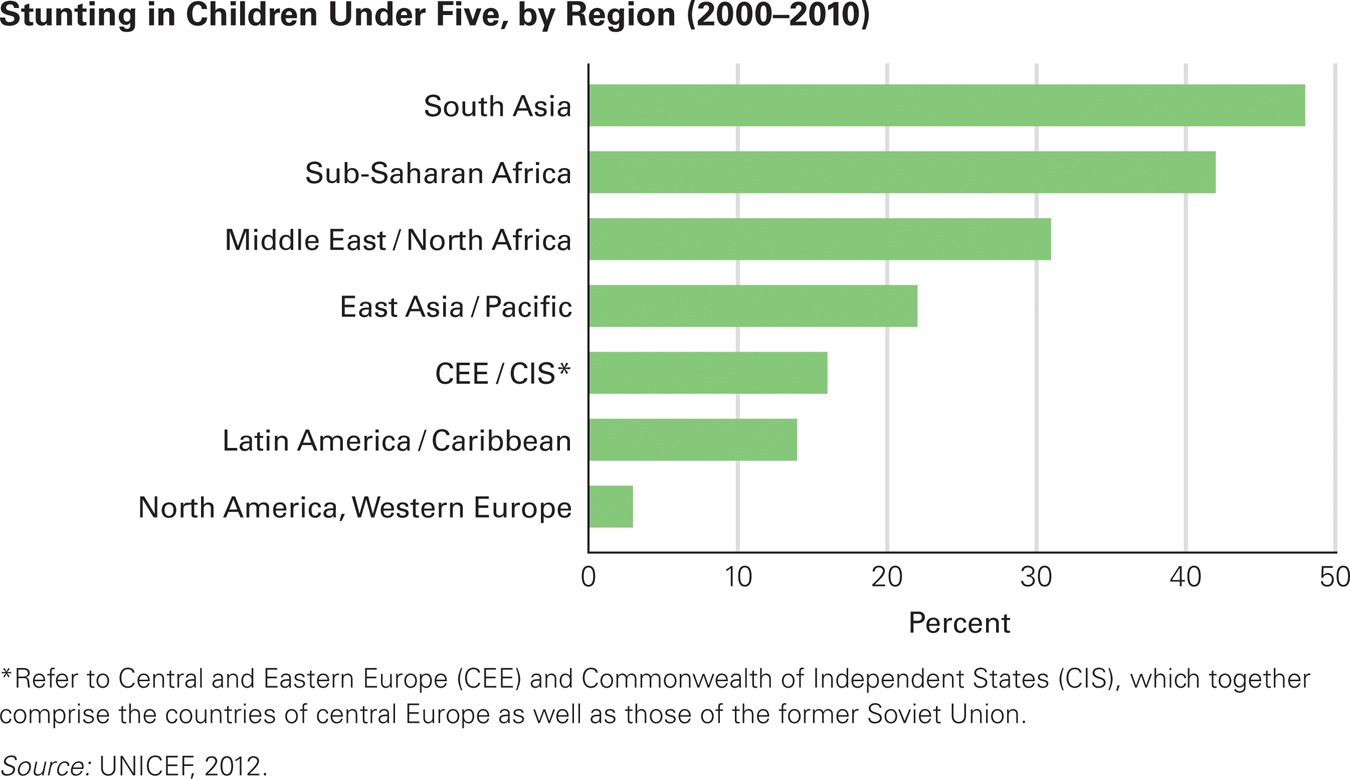

Even worse is wasting, when children are severely underweight for their age and height (2 or more standard deviations below average). Many nations, especially in East Asia, Latin America, and central Europe, have seen improvement in child nutrition in the past decades, with an accompanying decrease in wasting and stunting.

In some other nations, however, primarily in Africa, wasting has increased. And in several nations in South Asia, about one-

Chronically malnourished infants and children suffer in three additional ways:

Their brains may not develop normally. If malnutrition has continued long enough to affect height, it may also have affected the brain.

Malnourished children have no body reserves to protect them against common diseases. About half of all childhood deaths occur because malnutrition makes a childhood disease lethal.

Some diseases result directly from malnutrition—

both marasmus during the first year, when body tissues waste away, and kwashiorkor after age 1, when growth slows down, hair becomes thin, skin becomes splotchy, and the face, legs, and abdomen swell with fluid (edema).

Prevention, more than treatment, is needed. Sadly, some children hospitalized for marasmus or kwashiorkor die even after feeding because their digestive systems are already failing (M. Smith et al., 2013). Ideally, prenatal nutrition, then breast-

Some severely malnourished children still die. Researchers believe that for them, a combination of factors—

A study of two very poor African nations (Niger and Gambia) found several specific factors that reduced the likelihood of wasting and stunting: breast-

Several items on this list are taken for granted by readers of this book. However, two themes apply to everyone at any age: (1) Prevention is better than treatment, and (2) people with some knowledge tend to protect their health and that of their family. The next chapters continue these themes.

Genetic? The data show that basic nutrition is still unavailable to many children in the developing world. Some critics contend that Asian children are genetically small and therefore that Western norms make it appear as if India and Africa have more stunted children than they really do. However, children of Asian and African descent born and nurtured in North America are as tall as those of European descent. Thus, malnutrition, not genes, accounts for most stunting worldwide.

Video: Malnutrition and Children in Nepal shows the plight of children in Nepal who suffer from protein energy malnutrition (PEM).

SUMMING UP Various public health measures have saved billions of infants in the past century. Immunization protects those who are inoculated and also halts the spread of contagious diseases (via herd immunity). Smallpox has been eliminated, and many other diseases are rare except in regions of the world where public health professionals have not been able to establish best practices. In the United States, success at reducing childhood diseases have led some parents to refuse immunization completely, which may lead to an epidemic if herd immunity falls too low.

Breast milk is the ideal infant food, improving development for decades and reducing infant malnutrition and death. Fortunately, rates of breast-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 5.17

Why are immunization rates low in some African and South Asian nations?

Lack of access to vital immunizations contributes to low rates in some parts of these nations.Question 5.18

Why do doctors worry about immunization rates in the United States?

Parents' fears that immunizations can cause autism have led to a reluctance to immunize infants. Any negative effects of an immunization get reported in the media, fueling parents' concerns. However, several studies have refuted the link between immunization and autism, and the risk of a negative side effect of an immunization is minute compared to the risks associated with contracting the disease.Question 5.19

What are the reasons for and against breast-

feeding until a child is at least 1 year old? Breast–feeding has many benefits, including the fact that babies who are exclusively breast– fed are less often sick. In infancy, breast milk provides antibodies against any disease to which the mother is immune and decreases allergies and asthma. Babies who are exclusively breast– fed for six months are less likely to become obese and thus less likely to develop diabetes or heart disease. Formula feeding is preferable only in unusual cases, such as when the mother is HIV– positive or uses toxic or addictive drugs. Question 5.20

What is the relationship between malnutrition and disease?

Chronically malnourished children have no body reserves to protect them against common diseases, and some diseases result directly from malnutrition, including marasmus during the first year and kwashiorkor after age 1.Question 5.21

As an indication of malnutrition, which is better, stunting or wasting? Why?

Stunting is the failure of children to grow to a normal height for their age due to severe and chronic malnutrition. Even worse is wasting, the tendency for children to be severely underweight for their age as a result of malnutrition. Wasting can have a negative effect on brain development and often leads to disease, which is often times lethal.