Sensorimotor Intelligence

Video: Sensorimotor Intelligence in Infancy and Toddlerhood@2016 MACMILLAN

As you remember from Chapter 2, Jean Piaget was a Swiss scientist who earned his doctorate in 1918, when most scientists thought infants ate, cried, and slept but did not yet learn. When Piaget became a father, he used his scientific observation skills with his own babies. Contrary to conventional wisdom, he realized that infants are active learners, adapting to experience. His theories and observations have earned Piaget the admiration of developmentalists ever since. (Developmental Link: Piaget’s theory of cognitive development is introduced in Chapter 2.)

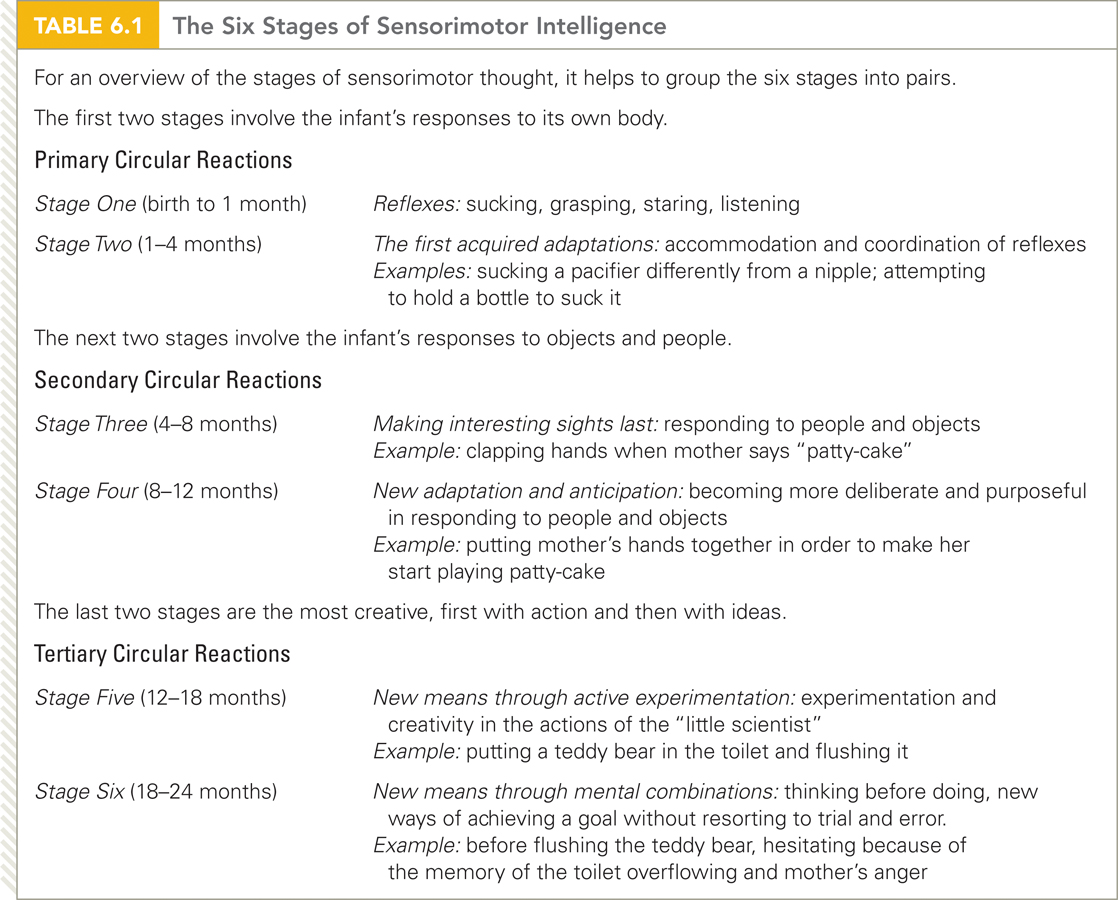

Piaget called cognition in the first two years sensorimotor intelligence, named about the early senses and motor skills described in Chapters 4 and 5. Those early reflexes and body movements are used by infants to develop their minds, adapting to experience. Sensorimotor intelligence is subdivided into six stages (see Table 6.1).

Stages One and Two: Primary Circular Reactions

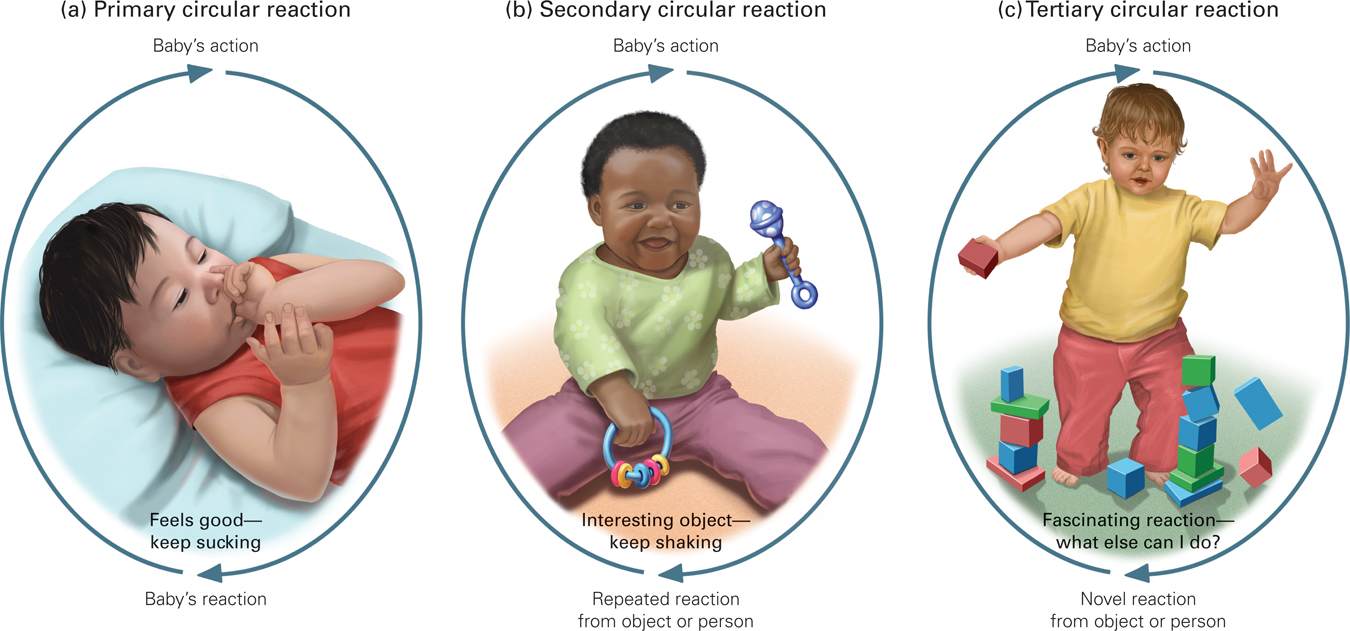

In every aspect of sensorimotor intelligence, the brain and the senses interact with experiences, each shaping the other as part of a dynamic system (Ambady & Bharucha, 2009). Piaget described the interplay of sensation, perception, and cognition as circular reactions, emphasizing that, as in a circle, there is no beginning and no end. Each experience leads to the next, which loops back (see Figure 6.1). The first two stages of sensorimotor intelligence are primary circular reactions, involving the infant’s body.

Never Ending Circular reactions keep going because each action produces pleasure that encourages more action.

Stage one, called the stage of reflexes, lasts only a month. It includes senses as well as motor reflexes, the foundations of sensorimotor thought. Soon reflexes become deliberate actions; sensation leads to perception, perception leads to cognition, and then cognition leads back to sensation.

Stage two, first acquired adaptations (also called stage of first habits), begins because reflexes adjust to whatever responses they elicit. Adaptation is cognitive; it includes both assimilation and accommodation. (Developmental Link: Assimilation and accommodation are explained in Chapter 2.) Infants adapt their reflexes as their responses teach them about what the body does and how each action feels.

Here is one example. In a powerful reflex, full-

During the first stage, in the first month, infants adapt their sucking reflex to bottles or breasts, pacifiers or fingers, each requiring specific types of tongue pushing. This adaptation signifies that infants have begun to interpret sensations; as they accommodate, they are “thinking.”

During stage two, which Piaget pegged from about 1 to 4 months of age, additional adaptation of the sucking reflex begins. Infant cognition leads babies to suck in some ways for hunger, in other ways for comfort—

Adaptation is quite specific. For instance, 4-

Stages Three and Four: Secondary Circular Reactions

In stages three and four, development advances from primary to secondary circular reactions. Those reactions extend beyond the infant’s body; this circular reaction is between the baby and something else.

During stage three (4 to 8 months), infants attempt to produce exciting experiences, making interesting sights last. Realizing that rattles make noise, for example, they wave their arms and laugh whenever someone puts a rattle in their hand. The sight of something delightful—

Especially for Parents When should parents decide whether to feed their baby only by breast, only by bottle, or using some combination of the two? When should they decide whether or not to let their baby use a pacifier?

Both decisions should be made within the first month, during the stage of reflexes. If parents wait until the infant is 4 months or older, they may discover that they are too late. It is difficult to introduce a bottle to a 4-

Next comes stage four (8 months to 1 year), new adaptation and anticipation (also called the means to the end). Babies may ask for help (fussing, pointing, gesturing) to accomplish what they want. Thinking is more innovative because adaptation is more complex. For instance, instead of always smiling at Grandpa, an infant might first assess his mood. Stage-

Pursuing a Goal

An impressive attribute of stage four is that babies work hard to achieve their goals. A 10-

At that age, babies indicate that they are hungry—

With a combination of experience and brain maturation, babies become attuned to the goals of others, an ability much more evident at 10 months than 8 months (Brandone et al., 2014). It seems that at Piaget’s fourth stage of sensorimotor intelligence, personal understanding begins to extend to social understanding.

Object Permanence

Piaget thought that, at about 8 months, babies first understand the concept of object permanence—the realization that objects or people continue to exist when they are no longer in sight. As Piaget discovered, not until about 8 months do infants search for toys that have fallen from the crib, rolled under a couch, or disappeared under a blanket. Blind babies also acquire object permanence toward the end of their first year, reaching for an object that they hear nearby (Fazzi et al., 2011).

As a recent statement of this phenomenon explains:

Many parents in our typical American middle-

[Xu, 2013, p. 167]

This excerpt describes Piaget’s classic experiment to measure object permanence: An adult shows an infant an interesting toy, covers it with a lightweight cloth, and observes the response. The results:

Infants younger than 8 months do not search for the object by removing the cloth.

At about 8 months, infants search removing the cloth immediately after the object is covered but not if they have to wait a few seconds.

At 18 months, they search quite well, even after a wait, but not if they have seen the object put first in one place and then moved to another. They search in the first place, not the second, a mistake called the A-

not- . Thus they search where they remember seeing it put (A), somehow not understanding that they saw it moved (to B). When a healthy, bright toddler exhibits this obvious failing, observers usually agree with Piaget: A-B error not- B is a sign of immature brain development, not a lack of innate intelligence. By 2 years, children fully understand object permanence, progressing through several stages of ever-

advanced cognition (Piaget, 1954/2013).

This research provides many practical suggestions. If young infants fuss because they see something they cannot have (keys, a cell phone, candy), caregivers are advised to put that coveted object out of sight. Fussing stops if object permanence has not yet appeared.

By contrast, for toddlers, hiding a forbidden object is not enough. It must be securely locked up or discarded, lest the child later retrieve it, climbing onto the kitchen counter or under the bathroom sink to do so. Since object permanence develops gradually, peek-

Piaget believed that failure to search before 8 months meant that infants had no concept of object permanence—

A series of clever experiments in which objects seemed to disappear behind a screen while researchers traced babies’ eye movements and brain activity revealed that long before 8 months, infants are surprised if an object vanishes (Baillargeon & DeVos, 1991; Spelke, 1993). The idea that such surprise indicates object permanence is accepted by some scientists, who believe that “infants as young as 2 and 3 months of age can represent fully hidden objects” (Cohen & Cashon, 2006, p. 224). Other scientists are not convinced (Mareschal & Kaufman, 2012).

Especially for Parents One parent wants to put all the breakable or dangerous objects away when the toddler is able to move around independently. The other parent says that the baby should learn not to touch certain things. Who is right?

It is easier and safer to babyproof the house because toddlers, being “little scientists,” want to explore. However, it is important for both parents to encourage and guide the baby. If having untouchable items prevents a major conflict between the adults, that might be the best choice.

Further research on object permanence continues to raise questions and produce surprises. For instance, many other creatures (cats, monkeys, dogs, birds) develop object permanence at younger ages than Piaget found. The animal ability seems to be innate, not learned, as wolves can develop it as well as dogs—

Stages Five and Six: Tertiary Circular Reactions

In their second year, infants start experimenting in thought and deed—

Tertiary circular reactions begin when 1-

Piaget’s stage five (ages 12 to 18 months), new means through active experimentation, builds on the accomplishments of stage four. Now goal-

Toddlers delight in squeezing all the toothpaste out of the tube, drawing on the wall, or uncovering an anthill—

Finally, in the sixth stage (ages 18 to 24 months), toddlers use mental combinations, intellectual experimentation via imagination that can supersede the active experimentation of stage five. Because they combine ideas, stage-

Thus, the stage-

Video: Event-

The ability to combine ideas allows stage six toddlers to pretend. For instance, they know that a doll is not a real baby, but they can belt it into a stroller and take it for a walk. At 22 months, my grandson gave me imaginary “shoe ice cream” and laughed when I pretended to eat it.

Piaget describes another stage-

who got into a terrible temper. He screamed as he tried to get out of a playpen and pushed it backward, stamping his feet. Jacqueline stood watching him in amazement, never having witnessed such a scene before. The next day, she herself screamed in her playpen and tried to move it, stamping her foot lightly several times in succession.

[Piaget, 1962, p. 63].

a view from science

Piaget and Modern Research

As detailed by hundreds of developmentalists, many infants reach the stages of sensorimotor intelligence earlier than Piaget predicted (Oakes et al., 2011). Not only do 5-

First, Piaget’s original insights were based on his own infants. Direct observation of three children is a start, and Piaget was an extraordinarily meticulous and creative observer, but no contemporary researcher would stop there. Given the immaturity and variability of babies, dozens of infants must be studied.

For instance, as evidence for early object permanence, Renée Baillargeon (2000) listed 30 studies involving more than a thousand infants younger than 6 months old. She and her collaborators continued to study object permanence with hundreds of infants, learning when and in what circumstances babies understand the concept, based not on one infant but on many infants of various backgrounds (e.g., Baillargeon et al., 2012).

Second, infants are not easy to study; there are problems with “fidelity and credibility” (Bornstein et al., 2005, p. 287). To overcome these problems, modern researchers use innovative statistics, research designs, sample sizes, and strategies that were not available to Piaget. As a result, contemporary scientists often find that object permanence, deferred imitation, and other sensorimotor accomplishments occur earlier, and with more variation, than Piaget had assumed (Carey, 2009). For instance, if an infant looks a few milliseconds longer when an object seems to have vanished, is that evidence of object permanence? Many researchers believe the answer is yes—

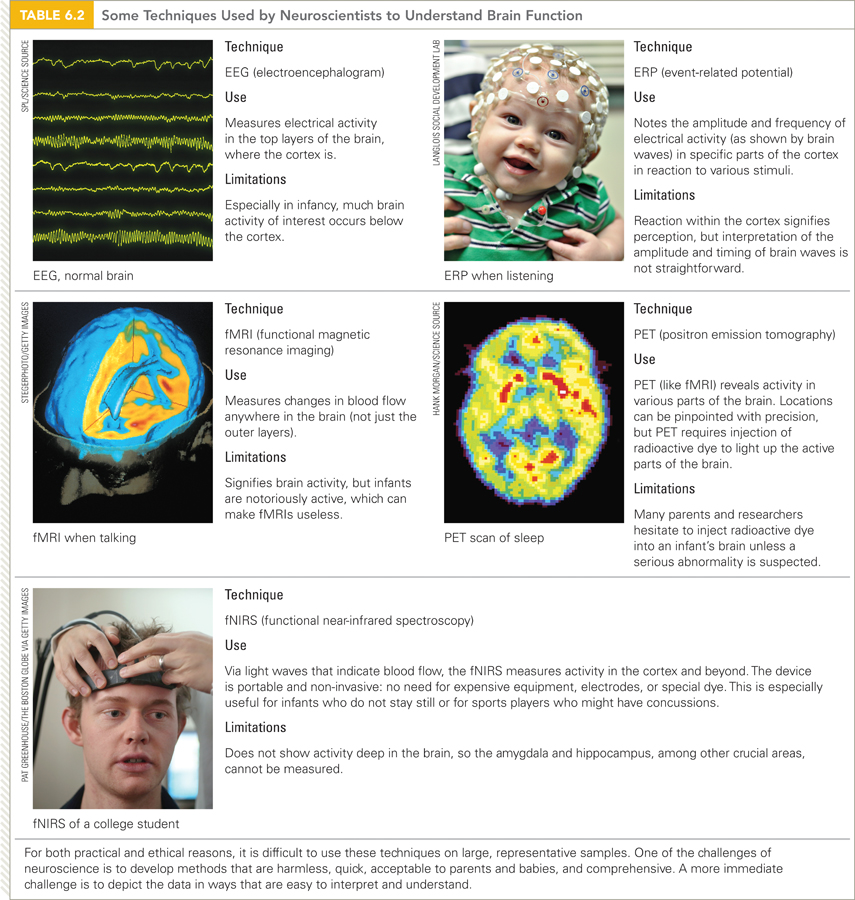

More to Come Hundreds of neuroscientists are developing new ways to perceive and analyze infant brain activity, as part of a $300 million dollar investment President Obama announced in 2014 as part of BRAIN (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies).

One particular research strategy has been a boon to scientists, confirming the powerful curiosity of very young babies. That research method is called habituation (from the word habit). Habituation refers to getting accustomed to an experience after repeated exposure, as when the school cafeteria serves macaroni day after day or when infants repeatedly encounter the same sound, sight, toy, or so on. Evidence of habituation is loss of interest (or, for macaroni, loss of appetite).

Using habituation as a research strategy with infants involves repeating one stimulus until babies lose interest and then presenting another, slightly different stimulus (a new sound, sight, or other sensation). Babies indicate that they detect a difference between the two stimuli with a longer or more focused gaze; a faster or slower heart rate; more or less muscle tension around the lips; a change in the rate, rhythm, or pressure of suction on a nipple. Such subtle indicators are recorded by technology that was unavailable to Piaget (such as eye-

By inducing habituation and then presenting a new stimulus, scientists have learned that even 1-

Third, several ways of measuring brain activity now allow scientists to record infant cognition before even subtle observable evidence is found (see Table 6.2) (Johnson, 2011). In fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging), a burst of electrical activity measured by blood flow within the brain is recorded, indicating that neurons are firing. This leads researchers to conclude that a particular stimulus has been noticed and processed. Scientists now know exactly which parts of the brain signify what sensations or thoughts, so electrical activity in the face area, for instance, means that the infants is processing a face. The current push to map the brain will make such discoveries more precise, allowing us to understand when the infant sees one face as rewarding and another as merely interesting.

Conclusions about early cognition are not accepted by every scientist, in part because brain imagery of normal infants is difficult and expensive. Brain scans may provide crucial information if an infant is seriously ill or injured, but many parents refuse to allow such measures on healthy infants. Further, infants fuss or move when neurological tests are underway, and hundreds of scans are needed for accurate conclusions. All this slows down neurological confirmation of infant cognition.

Nonetheless, as detailed in Chapter 5, early brain growth is rapid and wide-

For instance, one experiment found that when infants hear speech, their brains begin to react more notably (registered on ERPs, or event-

Despite several valid criticisms of Piaget’s work, he was correct in many ways. Infancy is a time for several distinct advances in cognition, and each new stage described by Piaget coincides with significant new connections in brain networks and functions. Piaget was right to describe babies as avid and active learners who “learn so fast and so well” (Xu & Kushnir, 2013, p. 28). His main mistake was underestimating how rapidly their learning occurs.

SUMMING UP Piaget discovered, studied, and then celebrated active infant learning, which he described in six stages of sensorimotor intelligence. Babies use senses and motor skills to understand their world, first with reflexes and then by adapting through assimilation and accommodation. Piaget’s detailed descriptions contrasted with earlier assumptions that babies did not think until they could talk. Thousands of researchers followed his lead, using advanced technology to demonstrate cognitive development of the early months.

We now know that object permanence, pursuit of goals, and deferred imitation all develop before the ages that Piaget assigned to his stages. The infant is a “little scientist” not only at 1 year, as Piaget described, but months earlier. Thinking develops before infants have the motor skills to demonstrate their thoughts; eye movements and brain scans find that babies have active minds. Nonetheless, the avid curiosity of the toddler, with the ability to imagine, pretend, and remember, is as notable and impressive today as it was for Piaget with his own children almost a century ago.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 6.1

Why did Piaget call his first stage of cognition sensorimotor intelligence?

Piaget called cognition in the first two years sensorimotor intelligence because infants learn through their senses and motor skills.Question 6.2

How do the first two sensorimotor stages illustrate primary circular reactions?

In every aspect of sensorimotor intelligence, the brain and the senses interact with experiences, each shaping the other. Sensation, perception, and cognition cycle in what Piaget called circular reactions. The first two stages of sensorimotor intelligence involve primary circular reactions, which involve the infant's own body.

Stage one, called the stage of reflexes, lasts only for a month. It includes senses as well as motor reflexes, the foundations of infant thought. Reflexes become deliberate; sensation leads to perception and then to cognition. Sensorimotor intelligence begins.

As reflexes adjust, the one–month– old enters stage two, first acquired adaptations (also called the stage of first habits). Adaptation is cognitive; it includes both assimilation and accommodation, which people use to understand their experience. Infants adapt their reflexes as repeated responses provide information about what the body does and how that action feels. Question 6.3

What is one example of how a stage-

three infant might make interesting events last? One example is a baby clapping her hands when her mother says “patty–cake.” Another example is a baby waving his arms and hands whenever someone puts a rattle in his hand. Question 6.4

How is object permanence an example of stage four of sensorimotor intelligence?

Piaget thought that at about 8 months babies first understand the concept of object permanence, the realization that objects or people continue to exist when they are no longer in sight. As Piaget predicted, not until about 8 months do infants search for toys that have fallen from the crib, rolled under a couch, or disappeared under a blanket. As they grow older, toddlers become better at seeking hidden objects, which Piaget again considered symptomatic of their sensorimotor intelligence.

If very young infants fuss because they want something they see but cannot have (your keys or a piece of candy), all an adult needs to do is put it out of sight. Fussing stops. By contrast, for toddlers, merely hiding the forbidden object is not enough. It must be securely locked or thrown away, or else a young child might remember where it is hidden and retrieve it.Question 6.5

In sensorimotor intelligence, what is the difference between stages five and six?

Stage five (ages 12 to 18 months) is called new means through active experimentation. This builds on the accomplishments of stage four. Now goal–directed and purposeful activities become more expansive and creative. Toddlers delight in squeezing all the toothpaste out of the tube, taking apart an iPod, and uncovering the anthill. Piaget referred to stage– five toddlers as “little scientists” who create “experiments in order to see.” Their scientific method is trial and error. Their devotion to discovery is familiar to every adult scientist and to every parent.

Also in the sixth stage, children are able to combine ideas. For instance, they know that a doll is not a real baby but can instead be a pretend baby, placed into a stroller and taken for a walk. Two words can be combined by this point as well, an impressive intellectual accomplishment.Question 6.6

What is now known about the sequence of object permanence, from before 6 months to after 2 years?

We now know that object permanence develops before the ages that Piaget assigned to his stages. The infant is a “little scientist” not only at 1 year as Piaget described but months earlier. Thinking develops before infants have the motor skills to demonstrate their thoughts; eye movements and brain scans find that babies have active minds.