Information Processing

As explained in Chapter 2, Piaget’s sweeping overview of four periods of cognition contrasts with information-

For infants, output might be moving a hand to uncover a toy (object permanence), saying a word to signify recognition (e.g., mama), or looking at one photo longer than another (habituation). Some recent studies examine changes in brain waves when infants see a picture (Kouider et al., 2013); such research both confirms and refutes Piaget’s theory.

To understand the many aspects of information processing in infancy, consider the baby’s reaction to an empty stomach. A newborn simply cries as a reflex to hunger pangs, but an older hungry infant hears Mother’s voice, looks for her, reaches to be picked up, and then nuzzles at her breast. Or, at an even older age, the toddler signs or says something to indicate hunger.

Each step of this process requires information to be processed. Older infants are more thoughtful and effective because of advanced information processing. Advances occur weekly or even day-

The information-

Especially for Computer Experts In what way is the human mind not like a computer?

In dozens of ways, including speed of calculation, ability to network across the world, and vulnerability to viruses. In at least one crucial way, the human mind is better: Computers become obsolete or fail within a few years, while human minds keep advancing for decades.

This perspective helps tie together many aspects of infant cognition. In earlier decades, infant intelligence was measured via age of sitting up, grasping, and so on, but we now know that age of achieving motor skills does not predict later intellectual achievement, although when an infant is way behind schedule (e.g., not sitting up at 8 months) that may indicate cognitive delay.

However, information-

Now let us look at two specific aspects of infant cognition that illustrate the information-

Affordances

Perception, remember, is the processing of information that arrives at the brain from the sense organs. Decades of thought and research led Eleanor and James Gibson to conclude that perception is far from automatic (E. J. Gibson, 1969; J. J. Gibson, 1979). Perception—

The environment (people, places, and objects) affords, or offers, many opportunities to interact with whatever is perceived (E. J. Gibson, 1997). Each of these opportunities is called an affordance. Which particular affordance is perceived and acted on depends on four factors: sensory awareness, immediate motivation, current level of development, and past experience.

As an example, imagine that you are lost in an unfamiliar city. You need to ask directions. Of whom? Not the first person you see. You want someone knowledgeable and approachable. Affordance is what you seek, and you scan the facial expression, body language, gender, dress, etc. of passersby (Miles, 2009). They, in turn, assess the affordance of your request. Are you genuinely lost, and do they know how to direct you? If they judge that your request is a scam, or they decide that your question is beyond them, their judgment of the affordance will force you to find another person.

Developmentalists studying children emphasize that age of the perceiver affects what affordances are perceived. For example, since toddlers enjoy running as soon as their legs allow it, every open space affords running: a meadow, a building’s long hall, a highway. To adults, affordance of running is much more limited: They worry about a bull grazing in the meadow, neighbors behind the hallway doors, or traffic on the road. Furthermore, because motivation is pivotal in affordances, toddlers move when most adults prefer to stay put.

Selective perception of affordances depends not only on age, motivation, and context but also on culture. Just as a baby might be oblivious to something adults consider crucial—

Variation in affordance is also apparent within cultures. City-

Research on Early Affordances

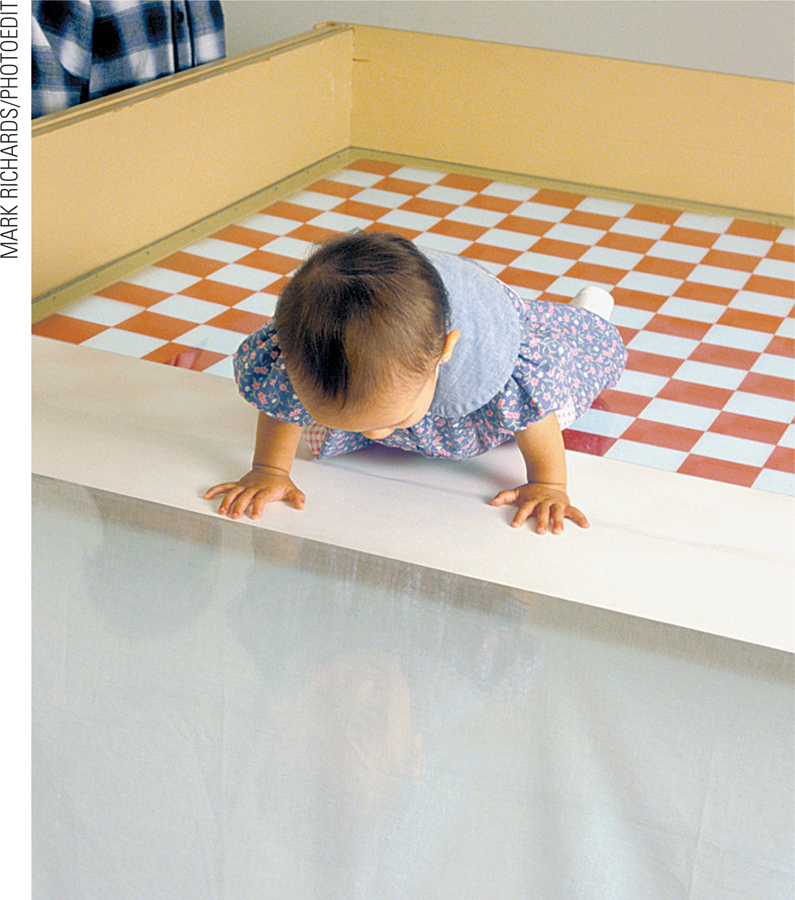

Experience affects which affordances are perceived. This is obvious in studies of depth perception. Research demonstrating this began with an apparatus called the visual cliff, designed to provide the illusion of a sudden drop-

Scientists once thought that a visual deficit—

Later research (using advanced technology) disproved that interpretation. Some 3-

Reaction to the visual-

Especially for Parents of Infants When should you be particularly worried that your baby will fall off the bed or down the stairs?

Constant vigilance is necessary for the first few years of a child’s life, but the most dangerous age is from about 4 to 8 months, when infants can move but do not yet fear falling over an edge.

A similar sequence happens with fear of many objects. By 9 months, infants attend to snakes and spiders more readily than to other similar images, but they do not yet fear them. A few months later, perhaps because they have learned from others, they are afraid of such creatures. Thus, perception is a prerequisite, but it does not always lead to affordance (LoBue, 2013).

Movement and People

Despite the variations from one infant to another in the particular affordances they perceive, all babies are attracted to two kinds of affordances. Babies pay close attention to things that move and to people.

Dynamic perception focuses on movement. Infants love motion. As soon as they can, they move their bodies—

It’s almost impossible to teach a baby not to chase and grab any moving creature, including a dog, a cat, or even a cockroach. Infants’ interest in motion was the inspiration for another experiment that sought to learn what affordances were perceived by babies too young to talk or walk (van Hof et al., 2008). A ball was moved at various speeds in front of infants aged 3 to 9 months. Most tried to touch or catch the ball as it passed within reach. However, marked differences appeared in their perception of the affordance of “catchableness.”

Sometimes younger infants did not reach for slow-

Another universal principle of infant perception is people preference. This follows from evolutionary psychology: Over the millennia, humans survived by learning to attend to, and rely on, one another. You just read that the affordance of the visual cliff depends partly on the tone of the mother’s voice. Infants soon recognize their caregivers and expect certain affordances (comfort, food, entertainment) from them.

Very young babies are particularly interested in emotional affordances, using their limited perceptual abilities and intellectual understanding to respond to smiles, shouts, and so on. Indeed, in one study, babies watched a three-

Given that infants are frequently exposed to their caregivers’ emotional displays and further presented with opportunities to view the affordances (Gibson, 1959, 1979) of those emotional expressions, we propose that the expressions of familiar persons are meaningful to infants very early in life.

[Kahana-

Building on earlier research design, these researchers tested their hypothesis by presenting infants with two moving images side by side on one video screen (Kahana-

Previous studies had found that 7-

These researchers first replicated the earlier experiments, again finding that 3½-month-

The researchers noticed something else as well. When infants saw and heard their happy mothers, they smiled twice as fast, seven times as long, and much more brightly (cheeks raised and lips upturned) than for the happy strangers. Experience had taught them that a smiling mother affords joy. The affordances of a smiling stranger are more difficult to judge.

Memory

Information-

There are several distinct types of memories, each in a particular part of the brain that is developing in its own way. That means that, even though infants already remember some things, other kinds of memory build and emerge throughout childhood. Instead of noting the many “faults and shortcomings relative to an adult standard,” it may be more appropriate to realize that children of all ages remember what they need to remember (Bjorklund & Sellers, 2014, p. 142). Sensory and caregiver memories are apparent in the first month, motor memories by 3 months, and then, at about 9 months, more complex memories (Mullally & Maguire, 2014).

Forget About Infant Amnesia

Video: Contingency Learning in Young Infants shows Carolyn Rovee-

The evidence suggests that infant amnesia, which is the belief that infants remember nothing, is mistaken. It is true that adults rarely remember events that occurred before they were 3. Children do somewhat better, remembering what happened at age 2. But the fact that memories fade with time does not mean that memory is absent.

If you forgot your third grade teacher’s name, for example, that does not mean that you had no memory when you were 9; it just means that you do not now remember what you could easily remember many years ago. And memory itself may be inaccessible, but not completely gone. If you saw a photo of your third grade teacher, and a list of four possible names for her or him, you probably could choose correctly.

No doubt memory is fragile in the first months of life and improves with age over the first months and years. Apparently a certain amount of experience and a certain amount of brain maturation are required in order to process and recall what happens (Bauer et al., 2010). But some of that experience happens on day one—

One reason for the apparent fragility is linguistic: People use words to store (and sometimes distort) memories, so preverbal children have difficulty with recall (Richardson & Hayne, 2007), while adults cannot access their infant memories because they did not yet have words to solidify them. Another probable reason is that memories fade over time: Adults cannot remember what happened when they were 1, but 2-

Conditions of Memory

Many studies seek to understand what infants can remember, even if they cannot later put memories into words. Memories are particularly evident if:

Motivation and emotion are high.

Retrieval is strengthened by reminders and repetition.

The most dramatic proof of infant memory comes from innovative experiments in which 3-

When some infants had the mobile-

Reminders and Repetition

The lead researcher in the mobile experiments, Carolyn Rovee-

In this particular reminder session, two weeks after the initial training, the infants watched the mobile move but were not tied to it and were positioned so that they could not kick. The next day, when they were again connected to the mobile and positioned so that they could move their legs, they kicked as they had learned to do two weeks earlier.

Apparently, watching the mobile move on the previous day had revived their faded memory. The information about making the mobile move was stored in their brains, but they needed processing time to retrieve it. The reminder session provided that time. Other research similarly finds that repeated reminders are more powerful than single reminders and that context is crucial, especially for infants younger than 9 months old: Being tested in the same room as the initial experience aids memory (Rovee-

A Little Older, a Little More Memory

After about 6 months of age, infants retain information for a longer time than younger babies do, with less training or reminding. Many researchers find that by 9 months, memory markedly improves, although it is not clear if this is purely maturational or if it is the result of locomotion, since 9-

Memory researchers now believe that several kinds of memory, lodged in various parts of the brain, reach an important level of maturation at about 9 months. For example, linguistic memory is evident when a baby’s vocalizations begin to sound like the speech he or she has heard. Motor memory is evident when an infant first watches someone else play with a new toy and, the next day, plays with it in the same way as he or she had observed. Infants younger than 9 months do not usually do this.

Many experiments show that 1-

The dendrites and neurons of the brain change to reflect remembered experiences during infancy. (Developmental Link: Experience-

The crucial insight from information processing is that the brain is a very active organ, changing with each day’s events. Therefore, the particulars of early experiences and memory are critically important in determining what a child knows or does not know.

Generalization becomes possible. At every age “people perceive more of a visual scene than was presented to them.” Even infants develop expectancies for what they observe and fill in the unseen parts (Mullally & Maguire, 2014).

Especially for Teachers People of every age remember best when they are active learners. If you had to teach fractions to a class of 8-

Remember the three principles of infant memory: real life, motivation, and repetition. Find something children already enjoy that involves fractions—

Many studies show that infants remember not only specific events and objects but also patterns and general goals (Keil, 2011). Some examples come from research, such as memory of what syllables and rhythms are heard and how objects move in relation to other objects. Additional examples arise from close observations of babies at home, such as what they expect from a parent or a babysitter, or what details indicate bedtime. Every day of their young lives, infants are processing information and storing conclusions.

SUMMING UP Information processing analyzes each component of how thoughts begin: how they are organized, remembered, and expressed, and how cognition builds, day by day. Infants’ perception is powerfully influenced by particular experiences and motivation; affordances perceived by one infant differ from those perceived by another. Memory depends on brain maturation and on experience. For that reason, memory is fragile in the first year (though it can be triggered by reminders) and becomes more robust, although still somewhat fragile, in the second year. In both perception and memory, babies are similar to adults in many ways—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 6.7

How do the affordances of this book, for instance, differ for someone at 1 month, 12 months, and 20 years of age?

The affordance of this book at 1 month is minimal at best; perhaps it offers the affordance of propping a baby up. At 12 months, the book's corners might make a great thing to chew on for a child who is teething or the pictures might engage a child briefly. At 20, the affordances are comprehending developmental psychology materials.Question 6.8

What are several hypotheses to explain why infants refuse to crawl over visual cliffs?

Initially, researchers assumed that younger infants were willing to cross the visual cliff because they could not perceive the difference in depth. Older infants refused to cross the cliff because their depth perception had developed adequately. Newer theories suggest that the infant's awareness of the affordance of the visual cliff depends on past experience. The difference is in processing, not input; in affordance, not mere stimulus. Further research on affordances of the visual cliff included the social context, with the tone of the mother's encouragement being a significant indicator of whether the cliff affords crawling or not.Question 6.9

What two preferences show that infants are selective in early perception?

Dynamic perception which is primed to focus on movement and change, and people preference, a universal principle of infant perception that reflects an innate attraction to other humans, reveals that infants are selective in their early perceptual skills.Question 6.10

What conditions help 3-

month- olds remember something? Researchers find that reminders help infants remember. In addition, the context is crucial, especially for infants younger than 9 months old.Question 6.11

How is infant memory similar to, and unlike, adult memory?

Information–processing research, with detailed behavioral and neurological measures, finds that memory is evident in very young babies. Within the first weeks after birth, infants recognize their caregivers by face, voice, and smell. Memory improves month by month. There are several distinct types of memories, each in a particular part of the brain that is developing in its own way. That means that, even though infants already remember some things, other kinds of memory build and emerge throughout childhood. Instead of noting the many “faults and shortcomings relative to an adult standard,” it may be more appropriate to realize that children of all ages remember what they need to remember. Sensory and caregiver memories are apparent in the first month, motor memories by 3 months, and then, at about 9 months, more complex memories.