Language: What Develops in the First TwoYears?

The brains of other species have nothing like the neurons and networks that support the 6,000 or so human languages. Many other animals communicate, but their language is primitive. The human linguistic ability at age 2 far surpasses that of full-

The Universal Sequence

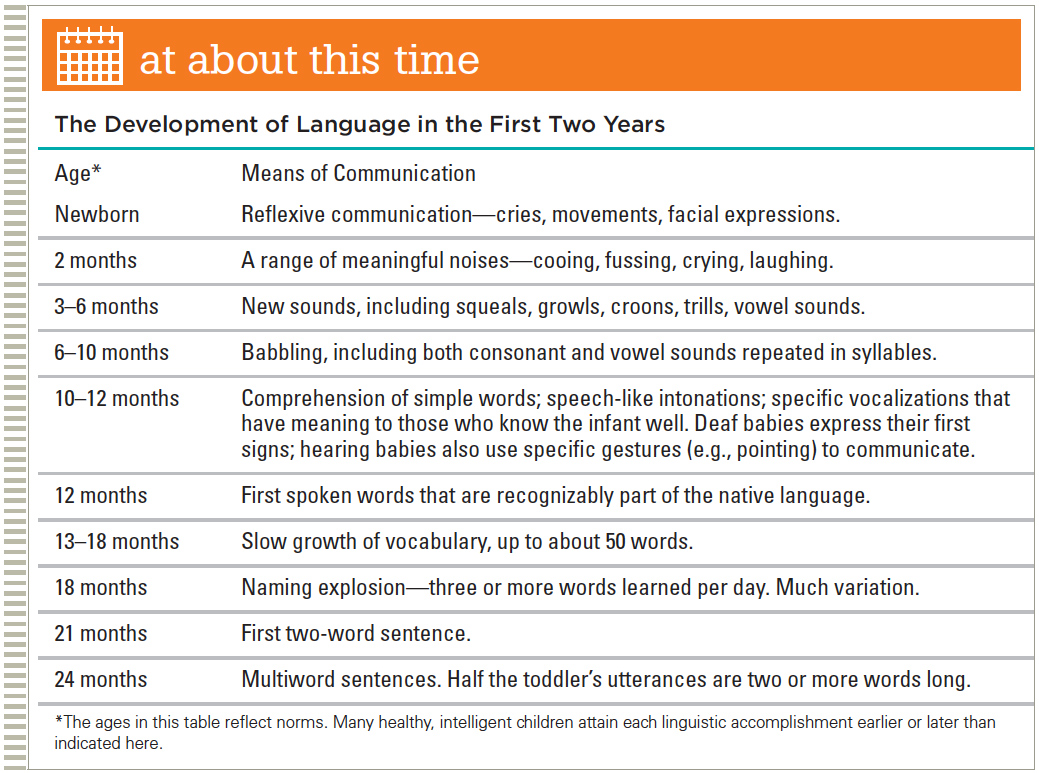

The sequence of language development is the same worldwide (see At About This Time). Some children learn several languages, some only one; some learn rapidly and others slowly, but they all follow the same path. Even deaf infants who become able to hear (thanks to cochlear implants) follow the sequence, catching up to their age-

Listening and Responding

Newborns prefer to listen to the language their mother spoke when they were in the womb, not because they understand the words, of course, but because they are familiar with the rhythm, the sounds, and the cadence.

Surprisingly, newborns of bilingual mothers differentiate between both languages (Byers-

The infants in all three groups sucked on a pacifier connected to a recording of 10 minutes of English or Tagalog matched for pitch, duration, and number of syllables. As evident in the frequency and strength of their sucking, most of the infants with bilingual mothers preferred Tagalog, presumably because their mothers were likely to speak English in formal settings but Tagalog when with family and friends, whereas those with monolingual mothers preferred English.

The Chinese bilingual babies (who had never heard Tagalog) nonetheless preferred it. The researchers believe that they liked Tagalog because the rhythm of that language is more similar to Chinese than to English (Byers-

Similar results, showing that babies like to hear familiar language, come from everyday life. Young infants attend to voices more than to mechanical sounds (a clock ticking) and look closely at the facial expressions of someone talking to them (Minagawa-

Infants’ ability to distinguish sounds they hear improves, whereas the ability to hear sounds never spoken in their native language (such as how an “r” or an “l” is pronounced) deteriorates (Narayan et al., 2010). If parents want a child to be fluent in two languages, they should speak both of them to their baby.

In every language, adults use higher pitch, simple words, repetition, varied speed, and exaggerated emotional tone when talking to infants (Bryant & Barrett, 2007). This special language form is sometimes called baby talk, since it is directed to babies, and sometimes called motherese, since mothers universally speak it. Nonmothers speak it as well. For that reason, scientists prefer the more formal term, child-

Especially for Nurses and Pediatricians The parents of a 6-

Urge the parents to learn sign language and investigate cochlear implants. Babbling has a biological basis and begins at a specified time, in deaf as well as in hearing babies. However, deaf babies eventually begin to use gestures more and to vocalize less than hearing babies. If their infant can hear, sign language does no harm. If the child is deaf, however, lack of communication may be devastating.

No matter what term is used, child-

Not only do infants prefer child-

Babbling and Gesturing

Between 6 and 9 months, babies repeat certain syllables (ma-

Toward the end of the first year, babbling begins to sound like the infant’s native language; infants imitate accents, cadence, consonants, and so on. Videos of deaf infants whose parents sign to them show that 10-

Many caregivers, recognizing the power of gestures, teach “baby signs” to their 6-

One early gesture is pointing, an advanced social gesture that requires understanding another person’s perspective. Most animals cannot interpret pointing; most 10-

Babbling and gesturing before speech vary from infant to infant—

First Words

Finally, at about 1 year, the average baby utters a few words, understood by caregivers if not by strangers. For example at 13 months, a child named Kyle knew standard words such as mama, but he also knew da, ba, tam, opma, and daes, which his parents knew to be, respectively, “downstairs,” “bottle,” “tummy,” “oatmeal,” and “starfish.” He also had a special sound that he used to call squirrels (Lewis et al., 1999).

Gradual Beginnings

In the first months of the second year, spoken vocabulary increases gradually (perhaps one new word a week). A 12-

Initially, the first words are merely labels for familiar things (mama and dada are common), but early words are soon accompanied by gestures, facial expressions, and nuances of tone, loudness, and cadence (Saxton, 2010). Imagine meaningful communication in “Dada,” “Dada?,” and “Dada!” Each is a holophrase, a single word that expresses an entire thought.

Intonation (variation in tone and pitch) is extensive in both babbling and holophrases, but there sometimes is a lull between the age of babbling and the age of recognizable words. Apparently at about 1 year, infants reorganize their vocalization from universal to language-

Uttering meaningful words takes all their attention—

The Naming Explosion

Spoken vocabulary builds rapidly once the first 50 words are mastered, with 21-

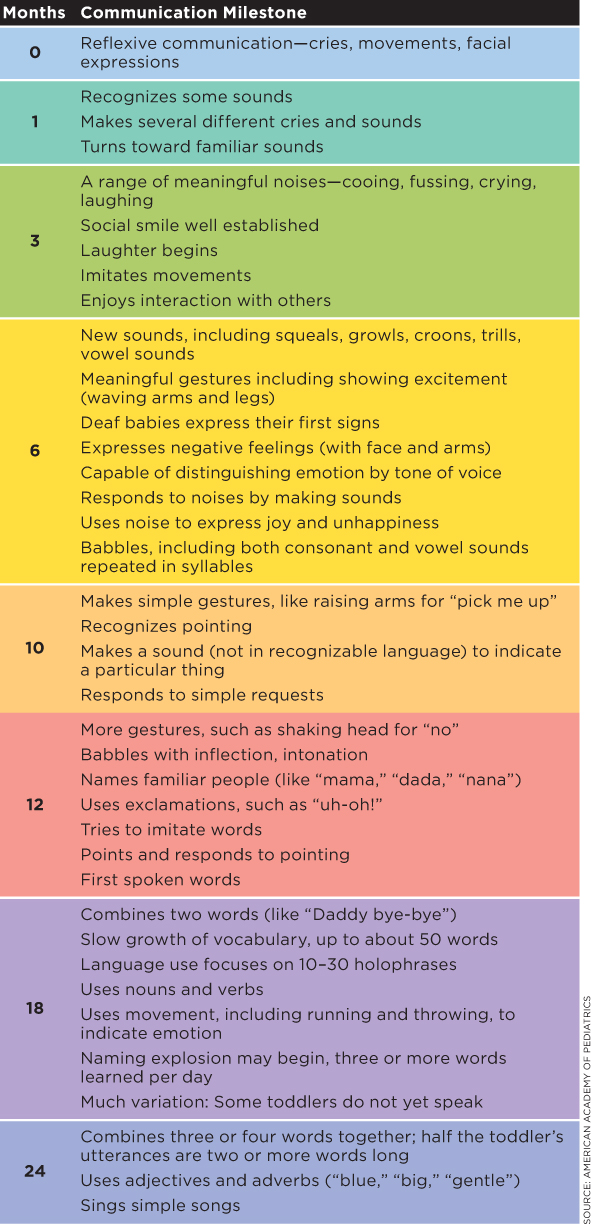

Between 12 and 18 months, almost every infant learns the name of each significant caregiver (often dada, mama, nana, papa, baba, tata) and sibling (and sometimes each pet). Other frequently uttered words refer to the child’s favorite foods (nana can mean “banana” as well as “grandma”) and to elimination (pee-

Notice that all these words have two identical syllables, each a consonant followed by a vowel. Many words follow that pattern—

Cultural Differences

Especially for Caregivers A toddler calls two people “Mama.” Is this a sign of confusion?

Not at all. Toddlers hear several people called “Mama” (their own mother, their grandmothers, their cousins’ and friends’ mothers) and experience mothering from several people, so it is not surprising if they use “Mama” too broadly. They will eventually narrow the label down to one person, unless both their parents are women. Usually such parents differentiate, with one called Mama and the other Mom, or both by their first names.

Cultures and families vary in how much child-

By 5 months, babies prefer adults who often use child-

Cultural differences are readily apparent in what linguistic sounds capture attention. Infants soon favor the words, accents, and linguistic patterns of their home language. For instance, a study of preverbal Japanese and French infants found that words with the first consonant at the front of the mouth and the second consonant at the back (as in “bat”) was preferred by infants in France, but the opposite (as in “tap”) was true in Japan. This was the case because of the language (French or Japanese) the babies had heard (Gonzalez-

The traditional idea that children should be “seen but not heard” is contrary to what developmentalists recommend and many contemporary families do—

Parts of Speech

Although all new talkers say names, use similar sounds, and prefer nouns more than other parts of speech, the ratio of nouns to verbs and adjectives varies from place to place (Waxman et al., 2013). For example, by 18 months, English-

One explanation goes back to the language itself. The Chinese and Korean languages are “verb-

An alternative explanation considers the entire social context: Playing with a variety of toys and learning about dozens of objects are routine in North America, whereas East Asian cultures emphasize human interactions—

Thus, Chinese toddlers might learn the equivalent of come, play, love, carry, run, and so on earlier. Indeed, 14-

A simpler explanation is that young children are sensitive to sounds. Verbs are learned more easily if they sound like the action (Imai et al., 2008), and such verbs are more common in some languages than others.

English does not have many onomatopoeic verbs, which makes verb-

Every language has some words and concepts that are difficult. English-

Putting Words Together

Grammar includes all the methods that languages use to communicate meaning. Word order, prefixes, suffixes, intonation, verb forms, pronouns and negations, prepositions and articles—

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Early Communication and Language Development

![]() COMMUNICATION MILESTONES: THE FIRST TWO YEARS

COMMUNICATION MILESTONES: THE FIRST TWO YEARS

These are norms. Many intelligent and healthy babies vary in the age at which they reach these milestones.

![]() UNIVERSAL FIRST WORDS

UNIVERSAL FIRST WORDS

Across cultures, babies’ first words are remarkably similar. The words for mother and father are recognizable in almost any language. Most children will learn to name their immediate family and caregivers between the ages of 12 and 18 months.

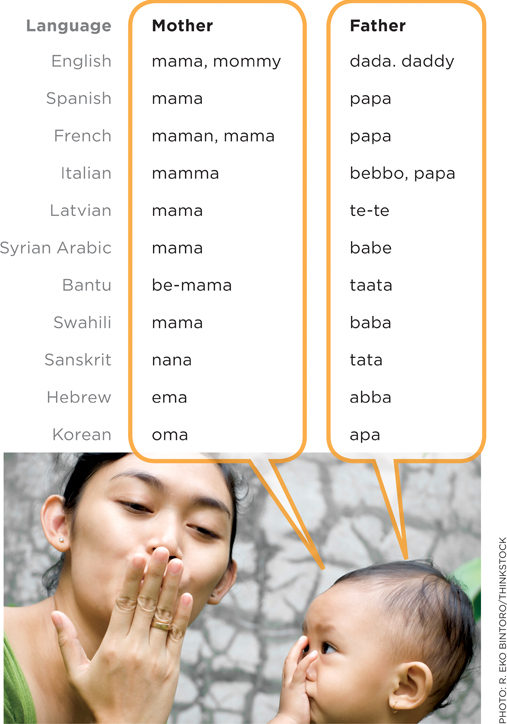

![]() MASTERING LANGUAGE (MLU)

MASTERING LANGUAGE (MLU)

Children’s use of language becomes more complex as they acquire more words and begin to master grammar and usage. A child’s spoken words or sounds (utterances) are broken down into the smallest units of language to determine their length and complexity:

For example, “Baby cry” and “More juice” follow grammatical word order. No child asks, “Juice more,” and even toddlers know that “cry baby” is not the same as “baby cry.” By age 2, children combine three words. English grammar uses subject–

Children’s proficiency in grammar correlates with the length of their sentences, which is why in every language mean length of utterance (MLU) is considered an accurate way to measure a child’s language progress (e.g., Miyata et al., 2013). The child who says “Baby is crying” is advanced compared with the child who says “Baby crying” or simply the holophrase “Baby.” (See Visualizing Development, p. 192.)

Young children can master two languages, not just one. Children are statisticians: They implicitly track the number of words and phrases and learn those expressed most often, in one, two, or more languages (Johnson & Tyler, 2010). (Developmental Link: Bilingual learning is discussed in detail in Chapter 9.) The toddler who often hears two languages will soon speak two languages.

Theories of Language Learning

Worldwide, people who are not yet 2 years old already speak their native language, or two or three languages if that is what they hear. They can express hopes, fears, and memories, and they continue to learn rapidly: All teenagers communicate with nuanced words and gestures, and some compose lyrics or deliver orations that move thousands of their co-

Answers come from three schools of thought, each connected to a theory introduced in Chapter 2: behaviorism, sociocultural theory, and evolutionary psychology. The first theory says that infants are directly taught, the second that social impulses propel infants to communicate, and the third that infants understand language because of brain advances several millennia ago that allowed survival of our species.

Theory One: Infants Need to Be Taught

The seeds of the first perspective were planted more than 50 years ago, when the dominant theory in North American psychology was behaviorism, or learning theory. The essential idea was that all learning is acquired, step-

B. F. Skinner (1957) noticed that spontaneous babbling is usually reinforced. Typically, every time the baby says “ma-

Skinner believed that most parents are excellent instructors, responding to their infants’ gestures and sounds, thus reinforcing speech (Saxton, 2010). Even in preliterate societies, parents use child-

The core ideas of this theory are the following:

Parents are expert teachers, although other caregivers help.

Frequent repetition is instructive, especially when linked to daily life.

Well-

taught infants become well- spoken children.

Behaviorists note that some 3-

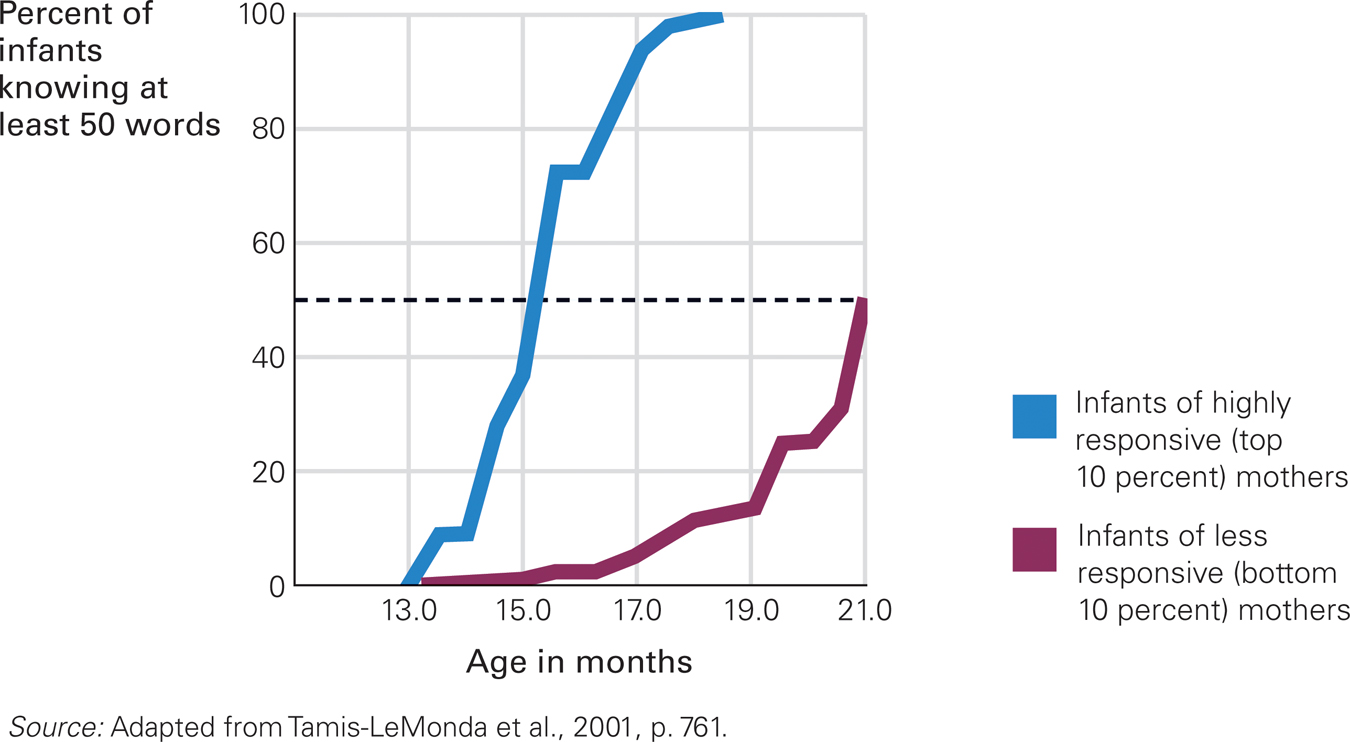

Maternal Responsiveness and Infants’ Language Acquisition Learning the first 50 words is a milestone in early language acquisition, as it predicts the arrival of the naming explosion and multiword sentences a few weeks later. Researchers found that half the 9-

In one detailed U.S. study, researchers analyzed a 10-

The frequency of maternal responsiveness at 9 months predicted language acquisition at 17 months. It was not that noisy infants, whose genes might soon make them verbal, elicited more talk. Some quiet infants had mothers who frequently suggested play activities, described things, and asked questions. Quiet infants with talkative mothers usually became more verbal toddlers than their peers.

Especially for Educators An infant daycare center has a new child whose parents speak a language other than the one the teachers speak. Should the teachers learn basic words in the new language, or should they expect the baby to learn the majority language?

Probably both. Infants love to communicate, and they seek every possible way to do so. Therefore, the teachers should try to understand the baby and the baby’s parents, but they should also start teaching the baby the majority language of the school.

According to behaviorists, if adults want children who speak, understand, and (later) read well, they must talk to their infants. A recent application of this theory comes from commercial videos, designed to advance toddlers’ vocabulary. Typically, such videos use repetition and attention-

opposing perspectives

Language and Video

Toddlers can learn to swim in the ocean, throw a ball into a basket, walk on a narrow path beside a precipice, call on a cell phone, cut with a sharp knife, play a guitar, say a word on a flashcard, recite a poem, utter a curse, and much more—

Commercial companies recognize that toddlers love learning and that parents are eager to teach. Infants are fascinated by dynamic activity, especially when it includes movement, sound, and people. This explains the popularity of child-

They are advertised with testimonials. Scientists consider such advertisement deceptive, since one case proves nothing and only controlled experiments prove cause and effect.

In fact, many scientists believe the truth is opposite the commercial claims. A famous study found that infants watching Baby Einstein were delayed in language compared to other infants (Zimmerman et al., 2007). The American Association of Pediatricians suggests no screen time (including television, tablets, smartphones, and commercial videos) for children under age 2.

These conclusions are not “robust.” That means that some interpretations of the evidence endorse prohibition, but others do not. Some scientists argue that the data are open to many conclusions, depending on the particular statistical analysis used (Ferguson & Donnellan, 2014).

An author of the original critique defended the anti-

Overall, most developmentalists find that, although some educational videos may help older children, videos during infancy are no “substitute for loving, face-

More specifically, there is a “transfer deficit” when infants learn from books and video screens, meaning they are less likely to understand and apply what they have learned than if they learned directly from another person (Barr, 2013). One solution is for caregivers to interact more with their infants and ban or limit videos. Another solution, if the parents want the child to learn vocabulary or other material from a book or video, is to let the child see the same two-

One product, My Baby Can Read, was pulled off the market in 2012 because experts repeatedly attacked its claims, and the cost of defending lawsuits was too high (Ryan, 2012). But many such products are still sold, and new ones appear continually. The owners of Baby Einstein lost a lawsuit in 2009, promised not to claim it was educational, and offered a refund, yet, as one critic notes:

The bottom line is that this industry exists to capitalize on the national preoccupation with creating intelligent children as early as possible, and it has become a multi-

[Ryan, 2012, p. 784]

Another study gave videos to one group of parents and none to a control group. They found no evidence that videos could actually teach young babies to read, or even recognize letters, although many parents in this study were enthusiastic about the videos (Neuman et al., 2014).

Is science too cautious or are parents too quick to be swayed by commercial testimony? If a video-

What is your opinion? More importantly, how does your opinion connect to your bias about scientists, or about corporations, or about parents?

Theory Two: Social Impulses Foster Infant Language

The second theory is called social-

According to this perspective, it is the emotional messages of speech, not the words, that propel communication. In one study, people who had never heard English (Shuar hunter-

Suppose an 18-

Evidence for social learning comes from educational programs for children. Many 1-

According to theory two, then, social impulses, not explicit teaching, lead infants to learn language. According to this theory, people differ from the great apes in that they are social, driven to communicate (Tomasello & Herrmann, 2010).

Theory Three: Infants Teach Themselves

A third theory holds that language learning is genetically programmed to begin at a certain age; adults need not teach it (theory one), nor is it a by-

As already explained in the research on memory, infants and toddlers observe what they see and they apply it—

This theory is buttressed by research that finds that variations in children’s language ability correlate with differences in brain activity and perceptual ability, evident months before the first words are spoken and apart from the particulars of parental input (Cristia et al., 2014). Some 5-

Especially for Nurses and Pediatricians Eric and Jennifer have been reading about language development in children. They are convinced that because language develops naturally, they need not talk to their 6-

Although humans may be naturally inclined to communicate with words, exposure to language is necessary. You may not convince Eric and Jennifer, but at least convince them that their baby will be happier if they talk to him.

This perspective began soon after Skinner proposed his theory of verbal learning. Noam Chomsky (1968, 1980) and his followers felt that language is too complex to be mastered merely through step-

Noting that all young children master basic grammar according to a schedule, Chomsky cited this universal grammar as evidence that humans are born with a mental structure that prepares them to seek some elements of human language. For example, everywhere, a raised tone indicates a question, and infants prefer questions to declarative statements (Soderstrom et al., 2011). This suggests that infants are wired to have conversations, and caregivers universally ask them questions long before they can answer back.

Chomsky labeled this hypothesized mental structure the language acquisition device (LAD). The LAD enables children, as their brains develop, to derive the rules of grammar quickly and effectively from the speech they hear every day, regardless of whether their native language is English, Thai, or Urdu. On their part, adults, because of their own LAD, instinctively help children learn whatever superficial differences appear between one language and another.

Other scholars agree with Chomsky that all infants are primed, naturally, to understand and speak whatever language they hear. They are eager learners, and speech becomes one more manifestation of neurological maturation (Wagner & Lakusta, 2009). This idea does not strip languages and cultures of their differences in sounds, grammar, and almost everything else, but the basic idea is that “language is a window on human nature, exposing deep and universal features of our thoughts and feelings” (Pinker, 2007, p. 148).

According to theory three, language is experience-

Research supports this perspective as well. As you remember, newborns are primed to listen to speech (Vouloumanos & Werker, 2007), and all infants babble ma-

Nature even provides for deaf infants. All 6-

A Hybrid Theory

Which of these three perspectives is correct? Perhaps all of them are true, to some extent. In one monograph that included details and results of 12 experiments, the authors presented a hybrid (which literally means “a new creature, formed by combining other living things”) of previous theories (Hollich et al., 2000). Since infants learn language to do numerous things—

Although originally developed to explain acquisition of first words, mostly nouns, this theory also explains learning verbs: Perceptual, social, and linguistic abilities combine to make that possible (Golinkoff & Hirsh-

One study supporting the hybrid theory began, as did the study previously mentioned, with infants looking at pairs of objects that they had never seen and never heard named. One of each pair was fascinating to babies and the other was boring, specifically “a blue sparkle wand … [paired with] a white cabinet latch … a red, green, and pink party clacker … [paired with] a beige bottle opener” (Pruden et al., 2006, p. 267). The experimenter said a made-

Unlike the similar study already described, which involved 18-

Current thinking is that children are not exclusively social learners or behaviorists and that learning a new word or grammar form is not an all-

This may be easier to understand with an example. Suppose a 1-

But then, a week later, the child might see Tom again, hear that his name is Tom, and immediately say “Tom.” The likely explanation is that partial learning occurred the first time, so the second time it became evident. Such experiences are common: A toddler might surprise everyone by saying a word that was heard earlier. Learning is more likely if all three factors (reinforcement, social impulses, maturation) combine.

After intensive study, yet another group of scientists also endorsed a hybrid theory, concluding that “multiple attentional, social, and linguistic cues” contribute to early language (Tsao et al., 2004, p. 1081). It makes logical and practical sense for nature to provide several paths toward language learning and for various theorists to emphasize one or another of them (Sebastián-

It also seems that some children learn better one way and others another way (Goodman et al., 2008), and that families and cultures vary in how they teach. Since every human must learn language, nature allows diversity in specifics so that the goal is always attained. Ideally, parents talk often to their infants (theory one), encourage social interaction (theory two), and appreciate the innate abilities of the child (theory three).

As one expert concludes:

our best hope for unraveling some of the mysteries of language acquisition rests with approaches that incorporate multiple factors, that is, with approaches that incorporate not only some explicit linguistic model, but also the full range of biological, cultural, and psycholinguistic processes involved.

[Tomasello, 2006, pp. 292–

The idea that every theory is correct may seem idealistic. However, many scientists who are working on extending and interpreting research on language acquisition arrive at a similar conclusion. They contend that language learning is neither the direct product of repeated input (behaviorism) nor the result of a specific human neurological capacity (LAD). Rather, from an evolutionary perspective, “different elements of the language apparatus may have evolved in different ways,” and thus, a “piecemeal and empirical” approach is needed (Marcus & Rabagliati, 2009, p. 281). In other words, no single theory explains how babies learn language: Humans accomplish this feat in many ways.

What conclusion can we draw from all the research on infant cognition? It is clear that infants are active learners of language and concepts and that they seek to experiment with objects and find ways to achieve their goals. This is the cognitive version of the biosocial developments noted in Chapter 5, that babies strive to roll over, crawl, walk, and so on as soon as they can. (See Visualizing Development, p. 192.)

SUMMING UP From the first days of life, babies attend to words and expressions, responding as well as their limited abilities allow—

The impressive language learning of the first two years can be explained in many ways: that caregivers must teach language, that infants learn because they are social beings, that inborn cognitive capacity propels infants to acquire language as soon as maturation makes that possible. Because infants vary in culture, learning style, and social context, a hybrid theory contends that each theory may be valid for explaining some aspects of language learning at some ages.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 6.12

What communication abilities do infants have before they talk?

By 6 months of age, babies engage in babbling, including consonant and vowel sounds, repeated in syllables. Infants in this age group also make use of gestures, especially pointing.Question 6.13

What aspects of early language development are universal, apparent in every culture?

In almost every language, the name of each significant caregiver and sibling is learned between 12 and 18 months. Other frequently uttered words refer to the child's favorite food and to elimination. A “naming explosion” takes place once children have around 50 words in their vocabularies. They prefer child–directed speech and are perhaps influenced by the language acquisition device proposed by Chomsky. Question 6.14

What is typical of the first words that infants speak and the rate at which they acquire them?

At about 1 year, the average baby utters his or her first words. First words are typically labels for familiar things, but each can convey many messages. “Dada!” “Dada?” and “Dada” may each be conveyed differently. Each is a holophrase, a single word that expresses an entire thought. Spoken vocabulary builds rapidly once the first 50 words are mastered with 21–month– olds typically saying twice as many words as 18– month– olds. This language spurt is called the naming explosion because many early words are nouns, that is, names of persons, places, or things. Question 6.15

What are the early signs of grammar in infant speech?

When infants start using two–word combinations, they use the proper word order. For example, no child asks, “Juice more.” Soon the child combines three words, usually in subject– verb– object order in English rather than any of the five other possible sequences of those words. Question 6.16

According to behaviorism, how do adults teach infants to talk?

Skinner believed that most parents are excellent instructors, replying to their infants' gestures and sounds, thus reinforcing speech. According to behaviorists, if adults want children who speak, understand, and (later) read well, they must talk to (and read to) their infants.Question 6.17

According to sociocultural theory, why do infants try to communicate?

According to sociocultural theory, infants communicate because humans have evolved as social beings, dependent on one another for survival and joy. Each culture has practices that further social interaction; talking is one of those practices.Question 6.18

What does the idea that child speech results from brain maturation imply for caregivers?

Since infants are innately ready to use their minds to understand and speak and because all infants are eager learners, a caregiver can rest assured that his or her baby will acquire language naturally, without specific lessons or effort on the caregiver's part. Language is experience–expectant, and most caregivers naturally adopt child– directed speech when talking to infants, so in most households, language acquisition proceeds normally.