Emotional Development

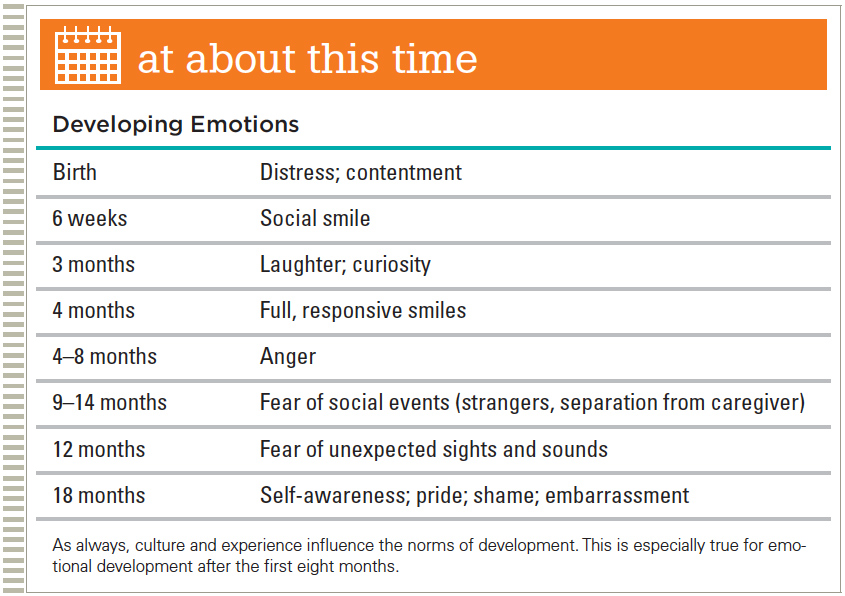

In their first two years, infants progress from reactive pain and pleasure to complex patterns of social awareness (see At About This Time), a movement from basic instinctual emotions to learned and then thoughtful ones (Panksepp & Watt, 2011). Infant emotions arise more from the body than from thought, so speedy, uncensored reactions—

Early Emotions

At first there is pleasure and pain. Newborns are happy and relaxed when fed and drifting off to sleep. They cry when they are hurt or hungry, tired or frightened (as by a loud noise or a sudden loss of support).

Some infants have bouts of uncontrollable crying, called colic, probably from immature digestion; some have reflux, probably from immature swallowing. About 20 percent of babies cry “excessively,” more than three hours a day, for more than three days a week, for more than three weeks (J. S. Kim, 2011).

Smiling and Laughing

Soon, additional emotions become recognizable. Curiosity is evident as infants (and people of all ages) respond to objects and experiences that are new but not too novel. Happiness is expressed by the social smile, evoked by a human face at about 6 weeks. Preterm babies smile a few weeks later because the social smile is affected by age since conception, not age since birth.

Infants worldwide express social joy, even laughter, between 2 and 4 months (Konner, 2007; Lewis, 2010). Laughter builds as curiosity does; a typical 6-

Anger and Sadness

The positive emotions of joy and contentment are soon joined by negative emotions, which are expressed more often in infancy than later on (Izard, 2009). Anger is evident at 6 months, usually triggered by frustration, such as when infants are prevented from moving or grabbing.

To investigate infants’ response to frustration, researchers “crouched behind the child and gently restrained his or her arms for 2 minutes or until 20 seconds of hard crying ensued” (Mills-

In infancy, anger is generally a healthy response to frustration, unlike sadness, which also appears in the first months. Sadness indicates withdrawal and is accompanied by a greater increase in the body’s production of cortisol.

This is one conclusion from experiments in which 4-

Since sadness produces physiological stress (measured by cortisol levels), sorrow negatively impacts the infant. All social emotions, particularly sadness and fear, probably shape the brain (Fries & Pollak, 2007; M. H. Johnson, 2011). As you learned in Chapter 5, experience matters. Sad and angry infants whose mothers are depressed become fearful toddlers (Dix & Yan, 2014). Too much sadness early in life correlates with depression later on.

Fear

Fear in response to some person, thing, or situation (not just being startled in surprise) is evident at about 9 months and soon becomes more frequent and obvious. Two kinds of social fear are typical:

Separation anxiety—clinging and crying when a familiar caregiver is about to leave

Stranger wariness—fear of unfamiliar people, especially when they move too close, too quickly

Separation anxiety is normal at age 1, intensifies by age 2, and usually subsides after that. Fear of separation interferes with infant sleep. For example, infants who fall asleep next to familiar people may wake up frightened if they are alone (Sadeh et al., 2010). The solution is not necessarily to sleep with the baby, but neither is it to ignore the child’s natural fear of separation. (Developmental Link: Co-

Some babies are comforted by a “transitional object,” such as a teddy bear or blanket beside them, as they transition from sleeping in their parents’ arms to sleeping alone. Music, a night light, an open door, may all ease the fear.

Transitional objects are not pathological; they are the infant’s way of coping with anxiety. However, if separation anxiety remains strong after age 3 and impairs the child’s ability to leave home, go to school, or play with friends, it is considered an emotional disorder. Separation anxiety as a disorder can be diagnosed at any age and is quite different from the “strong interdependence among family members,” which is normative in some cultures (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 193).

Separation anxiety may be apparent outside the home. Strangers—

Especially for Nurses and Pediatricians Parents come to you concerned that their 1-

Stranger wariness is normal up to about 14 months. This baby’s behavior actually might indicate secure attachment!

Many normal 1-

Every aspect of early emotional development interacts with cultural beliefs, expressed in parental actions. There seems to be more separation anxiety and stranger wariness in Japan than in Germany because Japanese infants “have very few experiences with separation from the mother,” whereas in German towns, “infants are frequently left alone outside of stores or supermarkets” while their mothers shop (Saarni et al., 2006, p. 237).

Toddlers’ Emotions

Emotions take on new strength during toddlerhood, as both memory and mobility advance (Izard, 2009). For example, throughout the second year and beyond, anger and fear become less frequent but more focused, targeted toward infuriating or terrifying experiences. Similarly, laughing and crying are louder and more discriminating.

The new strength of emotions is apparent in temper tantrums. Toddlers are famous for fury. When something angers them they might yell, scream, cry, hit, and throw themselves on the floor. Logic is beyond them; if adults respond with anger or teasing, that makes it worse.

One child was angry at her feet and said she did not want them. When a parent offered to get scissors and cut them off, a new wail of tantrum erupted. With temper tantrums, soon sadness comes to the fore, at which time comfort—

Social Awareness

Temper can be seen as an expression of selfhood. So can new toddler emotions: pride, shame, jealousy, embarrassment, disgust, and guilt. These emotions require social awareness, which typically emerges from family interactions. For instance, in a study of infant jealousy, when mothers deliberately paid attention to another infant, babies moved closer to their mothers, bidding for attention. Brain activity also registered social awareness (Mize et al., 2014).

Culture is crucial here, with independence a value in some families but not in others. Many North American parents encourage toddler pride (saying, “You did it yourself”—even when that is untrue), but Asian families typically cultivate modesty and shame. Such differences may still be apparent in adult personality and judgment. Are you more likely to be annoyed at people who brag or who say they failed? Probably family values taught you that reaction.

Disgust is also strongly influenced by other people as well as by maturation. According to a study that involved many children of various ages, many 18-

Self-Awareness

In addition to social awareness, another foundation for emotional growth is self-

Very young infants have no sense of self—

self-

[Thompson, 2006, p. 79]

In a classic experiment (Lewis & Brooks, 1978), 9-

However, at some time between 15 and 24 months, babies become self-

As another scholar explains it, “an explicit and hence reflective conception of the self is apparent at the early stage of language acquisition at around the same age that infants begin to recognize themselves in mirrors” (Rochat, 2013, p. 388). This is yet another example of the interplay of all the infant abilities—

SUMMING UP A newborn’s emotions are distress and contentment, expressed by crying or looking relaxed. The social smile is evident at about 6 weeks. Curiosity, laughter, anger (when infants are kept from something they want), and fear (when something unexpected occurs) soon appear, becoming evident in the latter half of the first year. At about a year, separation anxiety and stranger wariness peak, gradually fading as the child grows older. Toddlers become conscious that they are individuals apart from other individuals sometime after 15 months, and that allows them to experience and express many emotions that indicate self-

Video Activity: Self-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 7.1

What are the first emotions to appear in infants?

Crying and contentment are present from birth. The social smile appears around 6 weeks of age. Infants express social joy and laughter between 2 and 4 months.Question 7.2

What experiences trigger anger and sadness in infants?

Anger is evident at 6 months, usually triggered by frustration. Sadness usually indicates withdrawal and is accompanied by an increase in the body's production of cortisol, the primary stress hormone.Question 7.3

What do typical 1-

year- olds fear? Typical 1–year– old children fear strangers and separation from their caregivers. Many also fear anything unexpected, from the flush of the toilet to the pop of a jack– in– the– box. Question 7.4

How do emotions differ between the first and second year of life?

Emotions take on new strength during toddlerhood. For example, anger and fear become less frequent but more focused, targeted toward especially infuriating or terrifying experiences. Similarly, laughing and crying are louder and more discriminating. Social awareness develops, ushering in the new emotions of pride, shame, embarrassment, disgust, and guilt.Question 7.5

What is the significance of the toddler’s reaction to seeing herself in the mirror?

In a classic experiment, 9–to 24– month– olds looked into a mirror after a dot of rouge had been surreptitiously put on their noses. If they reacted by touching the red dot on their noses, that meant they knew the mirror showed their own faces. As one scholar explains it, “an explicit and hence reflective conception of the self is apparent at the early stage of language acquisition at around the same age that infants begin to recognize themselves in mirrors”