Injuries and Abuse

In almost all families of every income, ethnicity, and nation, parents want to protect their children while fostering their growth. Yet far more children die from violence—

The contrast between disease and accidental death is most obvious in developed nations, where medical prevention, diagnosis, and treatment make fatal illness rare until late adulthood. In the United States, four times as many 1-

Avoidable Injury

Worldwide, injuries cause millions of premature deaths among adults as well as children: Not until age 40 does any specific disease overtake accidents as a cause of mortality, and 14 percent of all life-

In some nations, malnutrition, malaria, and other infectious diseases combined cause more infant and child deaths than injuries do, but those nations also have high rates of child injury. India, for example, has one of the highest rates worldwide of child motor-

Age-Related Dangers

Why are young children so vulnerable? Some reasons have just been explained. Immaturity of the prefrontal cortex makes young children impulsive; they plunge into danger. Unlike infants, their motor skills allow them to run, leap, scramble, and grab in a flash, before a watching adult can stop them. Their curiosity is boundless; their impulses uninhibited. Then, if they do something that becomes dangerous, such as lighting a fire while playing with matches, fear and stress might make them slow to get help.

Age-

Injury Control

Instead of using the term accident prevention, public health experts prefer injury control (or harm reduction). Consider the implications. Accident implies that an injury is random, unpredictable; if anyone is at fault, it’s a careless parent or an accident-

Injury control suggests that the impact of an injury can be limited if appropriate controls are in place, and harm reduction implies that harm can be minimized. Minor mishaps (scratches and bruises) are bound to occur, but serious injury is unlikely if a child falls on a safety surface instead of on concrete, if a car seat protects the body in a crash, if a bicycle helmet cracks instead of a skull, or if swallowed pills come from a tiny bottle. Reducing harm from childhood behavior can be accomplished by a concerted effort of professionals and parents, as I know too well from my own experience described in the following A Case to Study.

a case to study

“My Baby Swallowed Poison”

The first strategy that most people think of to prevent injury to young children is to educate the parents. However, public health research finds that laws that apply to everyone are more effective than education, especially if parents are so overwhelmed by the daily demands of child care and money management that they do not realize they need to learn.

For example, infant car seats have saved thousands of lives. However, use of car seats is much less common when it is voluntary than when it is mandated. For that reason, car seats are now legally required.

Parents often consider safety a lower priority than everyday concerns. That explains two findings from the research: (1) The best time to convince parents to use a car seat is before they take their newborn home from the hospital, and (2) the best way to make sure a car seat is correctly used is to have an expert show the parents how it works—

Motivation and education are crucial, yet in real life, everyone has moments of foolish indifference. Then automatic safety measures save lives (Damashek & Kuhn, 2014).

I know this firsthand. Our daughter Bethany, at age 2, climbed onto the kitchen counter to find, open, and swallow most of a bottle of baby aspirin. Where was I? In the next room, nursing our second child and watching television. I did not notice what Bethany was doing until I checked on her during a commercial.

Bethany is alive and well today, protected not by her foolish mother but by all three levels of prevention explained on the next page. Primary prevention included laws limiting the number of baby aspirin per container, secondary prevention included my pediatrician’s written directions when Bethany was a week old to buy syrup of ipecac, and tertiary prevention was my phone call to Poison Control.

I told the helpful stranger who answered the phone, “My baby swallowed poison.” He calmly asked me a few questions and then advised me to give Bethany ipecac to make her throw up. I did, and she did.

In retrospect, I realize I had bought that ipecac two years before, when I was a brand-

I still blame myself, but I am grateful for all three levels of prevention that protected my child. In some ways, my own education helped avert a tragedy. I had chosen a wise pediatrician; I knew the number for Poison Control (FYI: 1-

Less than half as many 1-

Prevention

Prevention begins long before any particular child, parent, or legislator does something foolish. Unfortunately, no one notices injuries and deaths that did not happen. For developmentalists, two types of analysis are useful to predict danger and prevent it.

One is to look at all the systems that led to a serious injury. Causes can be found in the child, the microsystem, the exosystem, and the macrosystem, and thus measures can be taken to protect children in the future.

For example, when a child is hit by a car, it might be because the child was impulsive, the parents were neglectful (microsystem), the community was not child-

The second type of analysis involves understanding statistics. For example, the rate of childhood poisoning decreased markedly when pill manufacturers adopted bottles with safety caps that are difficult for children to open; such a statistic goes a long way in countering individual complaints about inconvenience. New statistics show a rise in the number of children being poisoned by taking adult recreational drugs, such as cocaine, alcohol, or marijuana, and that has led to new strategies for prevention (Fine et al., 2012).

Levels of Prevention

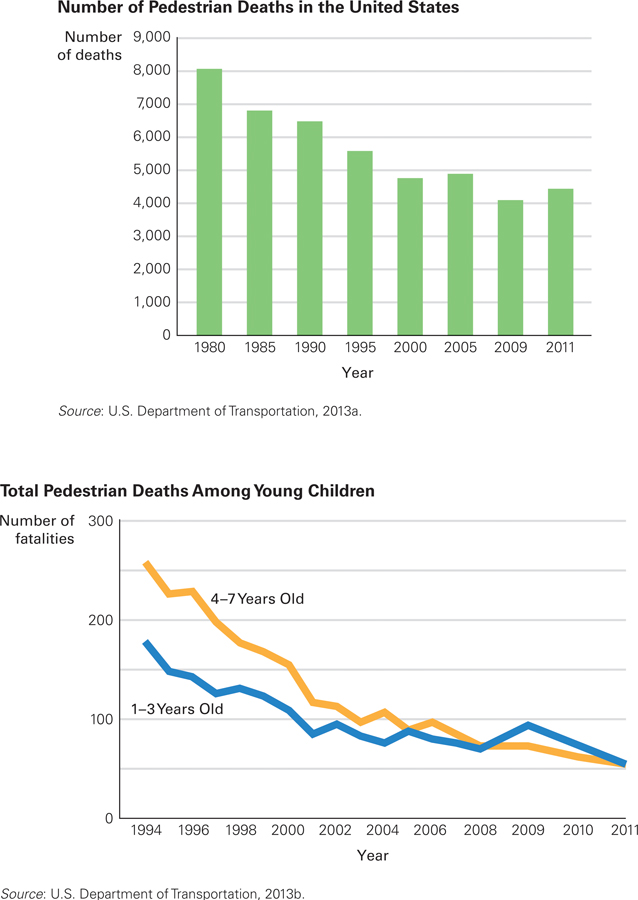

While the Population Grew This chart shows dramatic evidence that prevention measures are succeeding in the United States. Over the same time period, the total population has increased by about one-

Three levels of prevention apply to every health and safety issue.

In primary prevention, the overall situation is structured to make harm less likely. Primary prevention fosters conditions that reduce everyone’s chance of injury.

Secondary prevention is more specific, averting harm in high-

risk situations or for vulnerable individuals. Tertiary prevention begins after an injury has already occurred, limiting damage.

In general, tertiary prevention is the most visible of the three levels, but primary prevention is the most effective (Cohen et al., 2010). An example comes from data on pedestrian deaths. As compared with 20 years ago, fewer children in the United States today die after being hit by a motor vehicle (see Figure 8.5). How does each level of prevention contribute?

Primary prevention includes sidewalks, pedestrian overpasses, streetlights, and traffic circles. Cars have been redesigned (e.g., better headlights, windows, and brakes), and drivers’ competence has improved (e.g., stronger penalties keep many drunk drivers off the road). Reduction of traffic via improved mass transit provides additional primary prevention.

Secondary prevention reduces danger in high-

Finally, tertiary prevention reduces damage after an accident. Examples include laws against hit-

Especially for Urban Planners Describe a neighborhood park that would benefit 2-

The adult idea of a park–

Medical personnel speak of the golden hour, the hour following an accident, when a victim should be treated. Of course, there is nothing magical about 60 minutes in contrast to 61 minutes, but the faster an injury victim reaches a trauma center, the better the chance of survival (Dinh et al., 2013).

Culture and Injury Prevention: Baby on the Plane

I once was the director of a small preschool. I was struck by the diversity of fears and prevention measures, some helpful and some not. Some parents were thrilled that our children painted, but others worried about the ingredients of the paint, for instance. We had an outdoor sandbox; some parents thought that could give the children worms.

I knew that all children need to grab, run, and explore to develop their motor skills as well as their minds, yet they also need to be prevented from falling down stairs, eating pebbles, or running into the street—

Adults do not agree on the best strategies to prevent injury. Consider what one mother wrote about her flight from Australia to California:

I travelled with my 10-

I said that other people were able to move around the plane freely, why wasn’t she? I was told that due to turbulence she would have to be restrained for the whole trip. On several occasions the flight crew captain would make a point of going out of his way to almost scold me for not listening to him when I would put her down to crawl around.

[Retrieved April 3, 2011, from Complaints.com]

This same mother praised her treatment on other long flights, specifically on Asian airlines, when her child was allowed to move more freely and the crew was helpful. Which culture is better at protecting children without needlessly restraining them?

My sympathies were with the mother, and I praised the Asian crews, until I read this response:

Consider the laws in the U.S. regarding child safety in an automobile. Nobody thinks a child should be free to crawl around in a car. No parent thinks their rights have been violated because their child is prevented from free flight inside a car when it impacts. Why not just put the child in the bed of a truck and drive around? … Her child could get stepped on, slammed against a seat leg, wedged under a seat, fallen on, etc.

[Retrieved April 3, 2011, from Complaints.com]

Both sides in this dispute make sense, yet both cannot be right. The data prove that safety seats in cars save lives, but “impact” in planes is unlike that in a car crash. Statistical analysis is needed, or at least studies of injured children on airplanes, considering all the systems involved. Do passengers on planes step on crawling children? If so, is that controllable harm or a serious hazard?

SUMMING UP Worldwide, young children are more likely to be seriously hurt or killed accidently than they are to suffer from any specific disease. However, most such harm can prevented, which is why developmentalists prefer the term “injury control” rather than “accident prevention.” The contrast between death from disease and death from unintentional injury is particularly stark in the United States. Nonetheless, rates of such deaths have fallen since prevention is better understood. Three levels of prevention are crucial: primary (in the entire culture), secondary (for high-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 8.18

What can be concluded from the data on rates of childhood injury?

In almost all families of every income, ethnicity, and nation, parents want to protect their children while fostering their growth. Yet far more children die from violence—either accidental or deliberate— than from any specific disease. The contrast between disease and accidental death is most obvious in developed nations, where medical prevention, diagnosis, and treatment make fatal illness rare until late adulthood. In the United States, four times as many 1– to 4– year– olds die of accidents than of cancer, which is the leading cause of disease death during these years. In 2010, more young U.S. children were murdered (385) than died of cancer (346). This was not always true, but cancer deaths have decreased over the past half century while child homicide has increased. Question 8.19

How do injury deaths compare in developed and developing nations?

Worldwide, injuries cause millions of premature deaths among adults as well as children: Not until age 40 does any specific disease overtake accidents as a cause of mortality, and 14 percent of all life–years lost worldwide are caused by injury. In some nations, malnutrition, malaria, and other infectious diseases combined cause more infant and child deaths than injuries do, but those nations also have high rates of child injury. India, for example, has one of the highest rates worldwide of child motor– vehicle deaths; most children who die in such accidents are pedestrians. Everywhere, young children are at greater risk than slightly older ones. In the United States, 2– to 6– year– olds are more than twice as likely to be seriously hurt than 6– to 10– year– olds. Question 8.20

What are some examples of primary prevention?

Primary prevention reduces the likelihood of injury, abuse, or neglect. The installation of bike trails for bike riding creates and supports conditions that reduce a child's chance of injury. Access to parenting classes for vulnerable parents creates and supports conditions that reduce a child's chance of abuse or neglect.Question 8.21

What are some examples of secondary prevention?

Secondary measures reduce risk in high–risk situations. Examples include crosswalks and flashing lights on stopped school buses, which decrease the risk of injury. Preschool teachers and doctors who look for warning signs of abuse or neglect and report it for further investigation reduce the risk of harm for vulnerable children. Question 8.22

Why and how do cultures differ in determining acceptable risk?

In one example, a preschool teacher explains: Some parents were thrilled that our children painted, but others worried about the ingredients of the paint, for instance. We had an outdoor sandbox; some parents thought that could give the children worms. I knew that all children need to grab, run, and explore to develop their motor skills as well as their minds, yet they also need to be prevented from falling down stairs, eating pebbles, or running into the street—as many are inclined to do. That meant that teachers needed to balance freedom and prohibition. Yet the specifics of that balance are understood differently by various cultures. Adults do not agree on the best strategies to prevent injury.