Child Maltreatment

Especially for Criminal Justice Professionals Over the past decade, the rate of sexual abuse has gone down by almost 20 percent. What are three possible explanations?

Hopefully, more adults or children are aware of sexual abuse and stop it before it starts. A second possibility is that sexual abuse is less often reported and substantiated because the culture is more accepting of teenage sex (most victims of sexual abuse are between ages 10 and 18). A third possible explanation is that the increase in the number of single mothers means that fathers have less access to children (fathers are the most frequent sexual abusers).

Until about 1960, people thought child maltreatment was rare and consisted of a sudden attack by a disturbed stranger. Today we know better, thanks to a careful observation in one Boston hospital (Kempe & Kempe, 1978).

Maltreatment is neither rare nor sudden, and 82 percent of the time the perpetrators are the child’s parents (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013, December). That makes it much worse: Ongoing maltreatment, with no protector, is much more damaging than a single incident, however injurious.

Definitions and Statistics

Child maltreatment now refers to all intentional harm to, or avoidable endangerment of, anyone under 18 years of age. Thus, child maltreatment includes both child abuse, which is deliberate action that is harmful to a child’s physical, emotional, or sexual well-

To be specific, data on cases of substantiated maltreatment in the United States in 2012 indicate that 78 percent were cases of neglect, 18 percent of physical abuse, and 9 percent of sexual abuse. (A few were tallied in two categories) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013, December). Yet neglect is too often ignored by the public, who are “stuck in an overwhelming and debilitating” concept of maltreatment that focuses only on immediate bodily harm (Kendall-

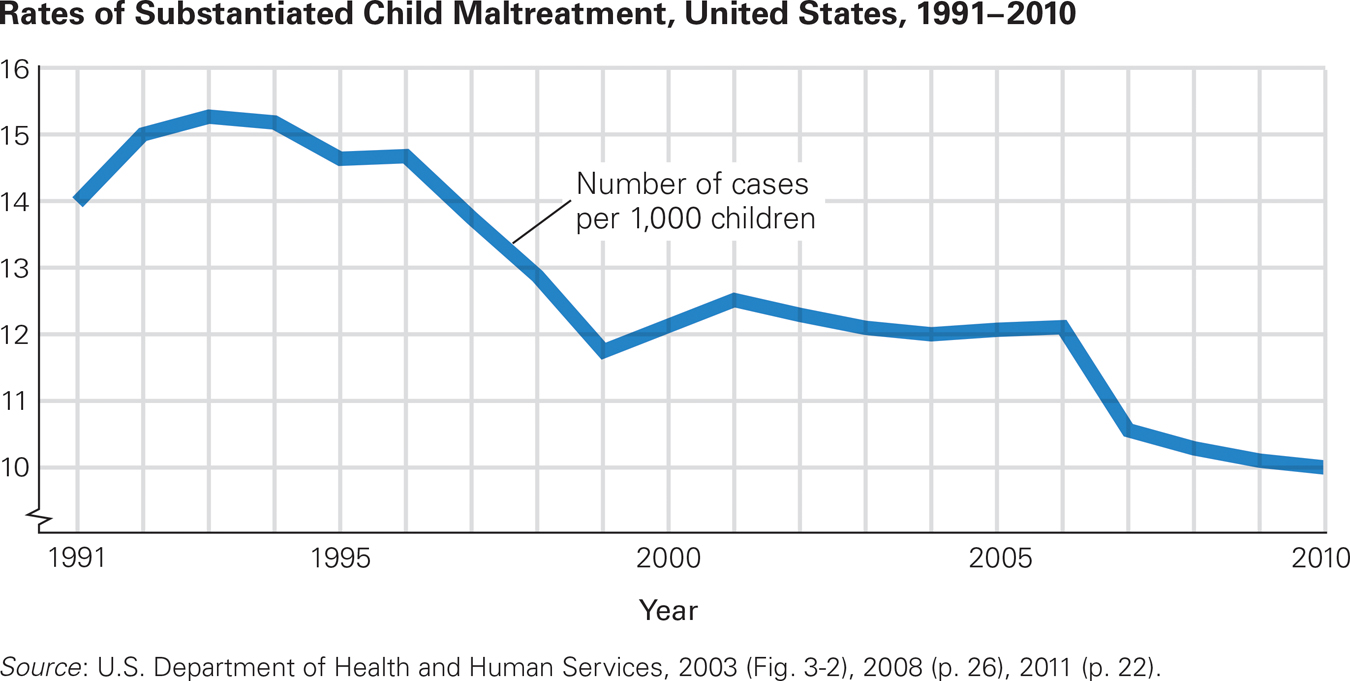

Substantiated maltreatment means that a case has been reported, investigated, and verified (see Figure 8.6). In 2012, almost 700,000 children suffered substantiated abuse in the United States. Substantiated maltreatment harms about 1 in every 90 children aged 2 to 5 annually.

Still Far Too Many The number of substantiated cases of maltreatment of children under age 18 in the United States is too high, but there is some good news: The rate has declined significantly from its peak in 1993.

OBSERVATION QUIZ The data point for 2010 is close to the bottom of the graph. Does that mean it is close to zero?

No. The number is actually 10.0 per 1,000. Note the little squiggle on the graph's vertical axis below the number 10. This means that numbers between 0 and 9 are not shown.

Reported maltreatment means simply that the authorities have been informed. Since 1993, the number of children reported as maltreated in the United States has ranged from about 2.7 million to 3.6 million per year, with 3.2 million in 2012 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013, December).

The 4.5-

Each child is counted only once, so five verified reports about a single child result in one substantiated case.

Substantiation requires proof. Not every investigation finds unmistakable harm or a witness willing to testify. Sometimes reports provide too little information, and the child cannot be located.

Many professionals are mandated reporters, required to report any signs of possible maltreatment. Often signs could be maltreatment, but investigation finds that no harm occurred (Pietrantonio et al., 2013).

Some reports are “screened out,” which means that the agency decides the case does not come under their jurisdiction, such as when a case belongs under the jurisdiction of the military or of a Native American tribe (who have their own systems).

A report may be false or deliberately misleading (though few are) (Sedlak & Ellis, 2014).

Frequency of Maltreatment

Especially for Nurses While weighing a 4-

Any suspicion of child maltreatment must be reported, and these bruises are suspicious. Someone in authority must find out what is happening so that the parent as well as the child can be helped.

How often does maltreatment actually occur? No one knows. Not all cases are noticed, not all that are noticed are reported, and not all reports are substantiated. Part of the problem is drawing the line between harsh discipline and abuse, and between momentary and ongoing neglect. Similar issues apply in every nation, city, and town, with marked variations in reports and confirmations. In general, only the most severe cases are tallied.

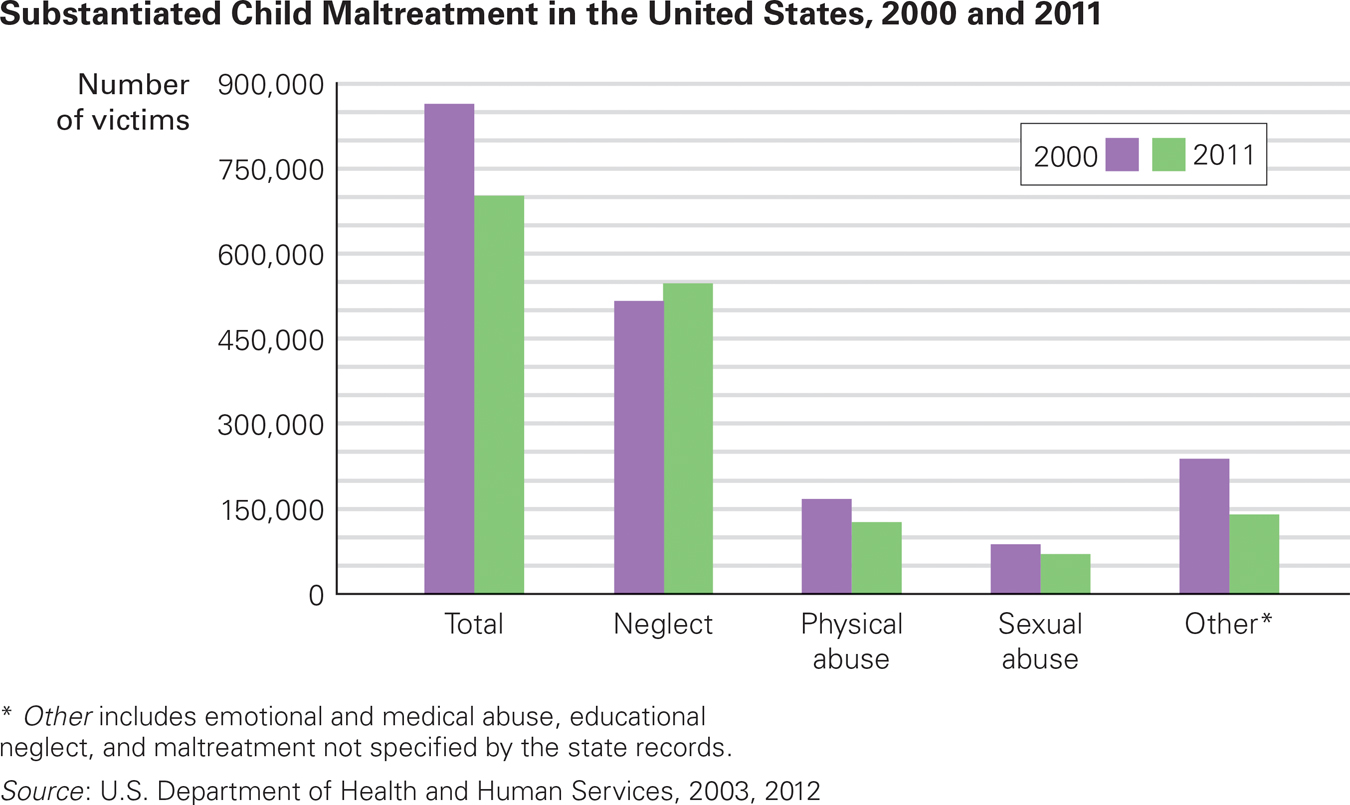

OBSERVATION QUIZ Have all types of maltreatment declined since 2000?

Most types of abuse are declining, but not neglect. This kind of maltreatment may be the most harmful because the psychological wounds last for decades.

If we rely on official U.S. statistics, trends are apparent. Officially, substantiated child maltreatment increased from about 1960 to 1990 but decreased thereafter (see Figure 8.7). Physical and sexual abuse declined, but neglect did not. Other sources also report declines, particularly in sexual abuse, over the past two decades. That seems to be good news; perhaps national awareness has led to better reporting and then better prevention.

Getting Better? As you can see, the number of victims of child maltreatment in the United States has declined in the past decade. The legal and social-

Accuracy of State Data

Unfortunately, official reports leave room for doubt. For example, Pennsylvania reports fewer victims of child maltreatment than Maine (3,416 compared to 3,781 in 2010), but the child population of Pennsylvania is ten times that of Maine. Why? It’s not lack of personnel: Pennsylvania has twenty times as many professionals screening and investigating (2831 to 145). Maybe it’s the definition of maltreatment: Less than 10 percent of the Pennsylvania victims are said to be neglected, but 66 percent are considered victims of sexual abuse, although nationwide only 9 percent of maltreated children are. Does that mean that the Pennsylvania laws ignore most children who would be considered victims if they lived in another state? Or are the overworked investigators in Maine too quick to confirm maltreatment?

How maltreatment is defined and whether or not it is reported is powerfully influenced by culture (one of my students asked, “When is a child too old to be beaten?”) and by personal willingness to report. The United States has become more culturally diverse; could that be why reports are down?

For developmentalists, a particular problem is that maltreatment is most common early in life, when children are too young to be required to go to school (where teachers would notice a problem) and too young to ask for help. In fact, infants have the highest rates of maltreatment, and 28 percent of all cases occur during early childhood (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013, December). Those are reported and substantiated cases; probably many more never reach outsiders’ attention.

Warning Signs

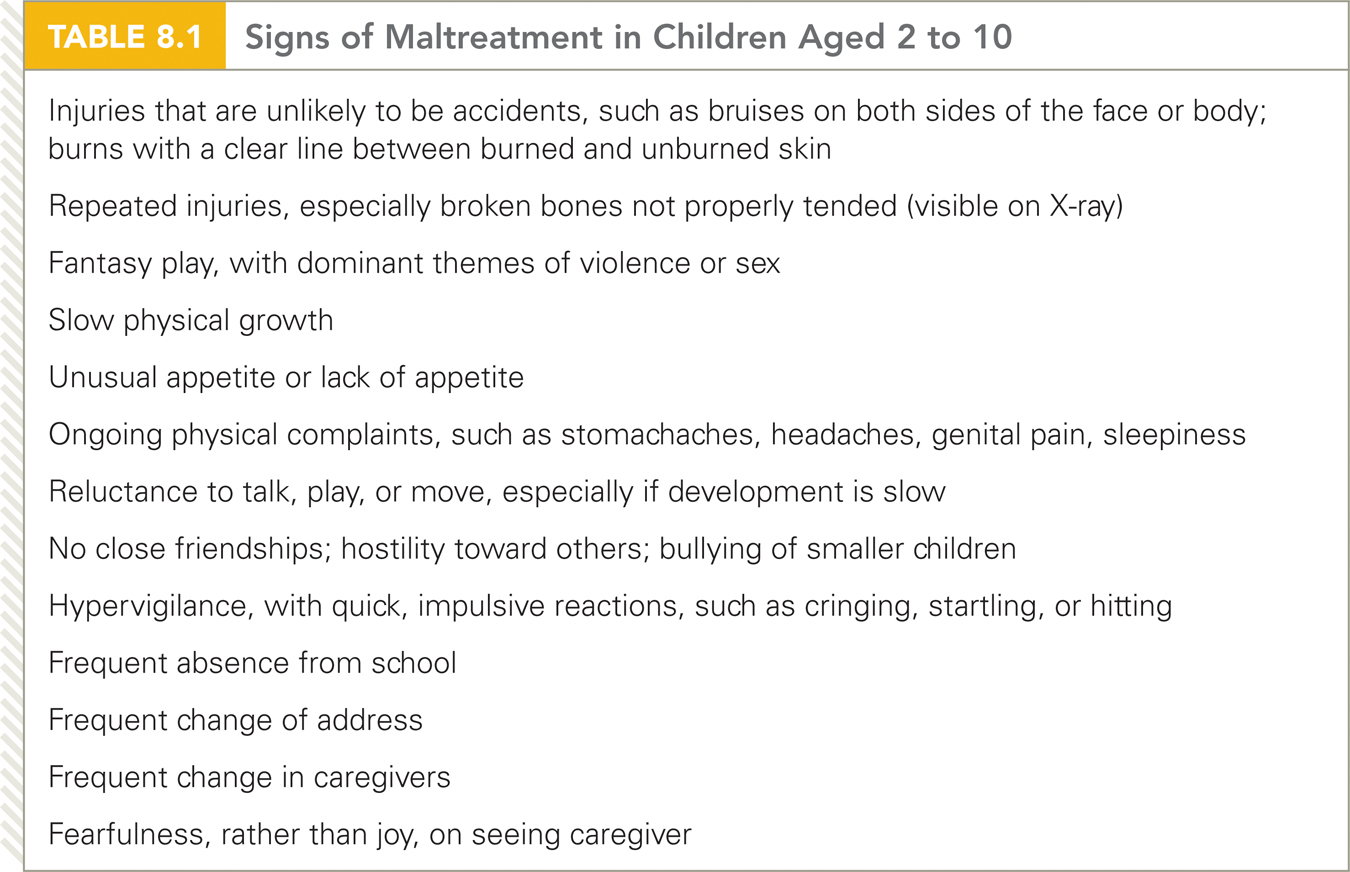

Instead of relying just on official statistics, every reader of this book can recognize developmental problems. Often the first sign of maltreatment is delayed development, such as slow growth, immature communication, lack of curiosity, or unusual social interactions. All these difficulties may be evident even at age 1, when they could be noticed by a relative or a neighbor. Unfortunately, many people do not know what is normal for infants (crying, clinging, smiling) and what is not (fear of caregiver, gaining less than a pound a month).

By early childhood, maltreated children may seem fearful, startled by noise, defensive and quick to attack, and confused between fantasy and reality. These are symptoms of post–

Table 8.1 lists signs of child maltreatment, both neglect and abuse. None of these signs is proof of abuse, but whenever any of them occurs, something is amiss.

Consequences of Maltreatment

The consequences of maltreatment involve not only the child but also the entire community. Regarding specifics, much depends on the community culture.

Customs and Maltreatment

The impact of any child-

However, although culture is always relevant, the impact of maltreatment is multifaceted and long-

Body and Brain

Developmentalists realize that the consequences of maltreatment include much more than the immediate harm. The biological and academic impairment resulting from maltreatment is obvious, as when a child is bruised, broken, afraid to talk, or failing in school.

However, when researchers follow maltreated children over the years, deficits in social skills seem more crippling than physical or intellectual damage. Maltreated children tend to hate themselves and then hate everyone else. Even if the child was mistreated early on and then not after age 5, emotional problems (externalizing for the boys and internalizing for the girls) linger (Godinet et al., 2014). The effects (drug abuse, social isolation, poor health) of maltreatment are still evident in adulthood (Sperry & Widom, 2013; Mersky et al., 2013).

Hate is corrosive. A warm and enduring friendship might repair some damage, but maltreatment makes friendship unlikely. Many studies have found that mistreated children typically regard other people as hostile and exploitative; hence, they are less friendly, more aggressive, and more isolated than other children. The earlier abuse starts and the longer it continues, the worse their relationships are, with physically and sexually abused children likely to be irrationally angry and neglected children often withdrawn (Petrenko et al., 2013).

Finding and keeping a job is a critical aspect of adult well-

This study is just one of hundreds of longitudinal studies, all of which find that maltreatment affects people decades after broken bones, or skinny bodies, or medical neglect disappear. To protect the health of the entire society in the future, prevention of child maltreatment is crucial.

Prevention

To halt child abuse and neglect, many measures of prevention are needed. Changes in the entire culture may be the most effective, but they also are the most difficult to implement.

Three Levels of Prevention

Just as with injury control, the ultimate goal with regard to child maltreatment is primary prevention, a social network of customs and supports that make parents, neighbors, and professionals protect every child. Neighborhood stability, parental education, income support, and fewer unwanted children all reduce maltreatment.

Secondary prevention involves spotting warning signs and intervening to keep a risky situation from getting worse. For example, insecure attachment, especially of the disorganized type, is a sign of a disrupted parent–

An important aspect of secondary prevention is reporting the first signs of maltreatment so that families can be helped before a child is damaged for life. Every parent and child interacts with several other people, who can notice signs of normal and abnormal development.

Some people are mandated reporters, professionals who are legally required to report signs of abuse. Together, they provide more than half of all reports in the United States; teachers and law enforcement personnel each provide about 17 percent of reports (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013, December). It is not their responsibility to be certain that abuse has occurred; that is the job of social workers who, as already mentioned, investigate.

Sometimes reports come from neighbors (5 percent) or relatives (7 percent). You might wonder why more lay people do not report abuse. One reason is ignorance: Many abusers deliberately change residences and break off contact with relatives. That in itself is a sign of trouble. Another reason is that people fear the anger of the abuser or worry that the officials will makes things worse.

Tertiary prevention limits harm after maltreatment has occurred. Reporting and substantiating abuse are the first steps. Often the caregiver needs help in providing better care. Sometimes the child needs another home.

Permanency Planning

All levels of prevention require helping caregivers provide a safe, nurturing, and stable home. This is true for biological parents, a foster family, or an adoptive family. Whenever a child is removed from an abusive or neglectful home, permanency planning is needed: That means that plans need to be made to nurture the child until adulthood—

In foster care, children are officially taken from their parents and entrusted to another adult or family; foster parents are reimbursed for the expenses they incur in meeting the children’s needs. In every year from 2000 to 2014, almost half a million children in the United States were in foster care. Many of them were in a special version of foster care called kinship care, in which a relative—

In every nation, most foster children are from low-

Adequate support is not typical, however. One obvious failing is that many children move from one foster home to another for reasons that are unrelated to the child’s behavior or wishes (Jones & Morris, 2012). Each move increases the risk of a poor outcome. Another problem is that kinship care is sometimes used as an easy, less expensive solution.

Supportive services are especially needed in kinship care, since the grandparent typically lives in the same community of poverty, racism, and/or violence that contributed to the original problems. All of this affects the foster child as well (Hong et al., 2011).

Most adults, even in the most troubled communities, want success for children and do their best to provide it. Many adults raised by grandparents fare well, but grandparents need even more help from friends, relatives, and agencies than parents, yet they are less likely to get it.

Adoptive Homes

Adoption (when an adult or couple is legally granted parenthood) is the best permanent option when a child should not be returned to a parent (Scott et al., 2013). However, adoption is difficult for many reasons, including the following:

Judges and biological parents are reluctant to release children for adoption.

Most adoptive parents prefer infants, so it is harder to find adoptive homes for older children.

Some agencies screen out families not headed by a heterosexual married couple.

Some professionals insist that adoptive parents be of the same ethnicity and religion as the child.

Kinship caregivers are reluctant to sever the parental rights of their child or other relative.

As detailed many times in this chapter, caring for young children is not easy, whether it involves making them brush their teeth or keeping them safe from harm. Parents shoulder most of the burden, and their love and protection usually result in strong and happy children. Beyond the microsystem, however, complications abound. Adults are failing many young children, as statistics throughout this chapter reveal. The entire community benefits from well-

SUMMING UP Although abuse seems to have decreased in the United States as more of the public has become aware of it, still about 700,000 children are tallied each year as maltreated—

In primary prevention, laws and customs need to protect every child, with measures to reduce poverty, to strengthen families, and to nurture all children. In secondary prevention, supervision, forethought, and protective care can prevent harm to those at risk, with signs of neglect and abuse apparent in the first months of life, and obvious by early childhood. In tertiary prevention, quick and effective medical and psychosocial intervention is needed when injury or maltreatment occurs. Foster care and adoption are sometimes best for children, but these options are not as available as they need to be. Putting an end to maltreatment of all kinds is urgent, but this goal is difficult to achieve because changes are needed in families, cultures, communities, and laws.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 8.23

Why did few people recognize childhood maltreatment 50 years ago?

Prior to the late 1970s there was no research on the topic. It was a common belief that child maltreatment was a rare, sudden attack perpetrated by a disturbed stranger. Today, we know that maltreatment is neither rare nor sudden, and 80 percent of the perpetrators are one or both of the child's parents.Question 8.24

Why is neglect in childhood considered more harmful than abuse in the long term?

Neglected children may have greater social deficits than abused ones because they were unable to relate to their parents. They may also suffer the long–term effects of neglected nutritional and physical needs. Question 8.25

Why is it difficult to know exactly how often child maltreatment occurs?

U.S. laws now require teachers and other professionals to report suspected maltreatment. Thus, reports have increased because of those laws. Yet not all cases are noticed, reported, or substantiated. There is a 3:1 ratio of reported to substantiated cases because each child is substantiated only once (even though there may be multiple reports), substantiation requires proof, signs of maltreatment reported by mandatory reporters may turn out to have benign explanations, and a report may be deliberately misleading (rarely).Question 8.26

What are the common signs that indicate a child may be maltreated?

Signs of possible maltreatment include delayed development (such as slow growth, immature communication, lack of curiosity, or unusual social interactions), excessive fearfulness, a heightened startle response, defensiveness, and confusion about the difference between fantasy and reality.Question 8.27

What are the long-

term consequences of childhood maltreatment? Maltreated children may become bullies, victims, or both, not only in childhood and adolescence but also in adulthood. They tend to dissociate, that is, to disconnect their memories from their understanding of themselves. Adults who were severely maltreated (physically, sexually, or emotionally) often abuse drugs or alcohol, enter unsupportive relationships, become victims or aggressors, sabotage their own careers, eat too much or too little, and engage in other self–destructive behavior. Question 8.28

What are the advantages and disadvantages of foster care?

In every nation, most foster children are from low–income, ethnic– minority families— a statistic that reveals problems in the macrosystem as well as the microsystem. In the United States, children in foster care often have experienced severe maltreatment and have multiple physical, intellectual, and emotional problems. Most develop better in foster care (including kinship care) than with their original abusive families if a supervising agency provides ongoing financial support and counseling. Adequate support is not typical, however. One obvious failing is that many children move from one foster home to another for reasons that are unrelated to the child's behavior or wishes. Each move increases the risk of a poor outcome. Question 8.29

Why does permanency planning rarely result in adoption?

Whenever a child is removed from an abusive or neglectful home, permanency planning is needed: That means that plans need to be made to nurture the child until adulthood—either by supporting the original family or finding another home. However, this is especially difficult in adoption for the following reasons:  Judges and biological parents are reluctant to release children for adoption.

Judges and biological parents are reluctant to release children for adoption. Most adoptive parents prefer infants, so it is harder to find adoptive homes for older children.

Most adoptive parents prefer infants, so it is harder to find adoptive homes for older children. Some agencies screen out families not headed by a heterosexual married couple.

Some agencies screen out families not headed by a heterosexual married couple. Some professionals insist that adoptive parents be of the same ethnicity and religion as the child.

Some professionals insist that adoptive parents be of the same ethnicity and religion as the child. Kinship caregivers are reluctant to sever the parental rights of their child or other relative.

Kinship caregivers are reluctant to sever the parental rights of their child or other relative.