Thinking During Early Childhood

You have just learned in Chapter 8 that every year of early childhood advances motor skills, brain development, and impulse control. In Chapter 6, you learned about the impressive development of memory and language in the first two years of life. Each of these developmental advances affects cognition. Thinking during early childhood is multi-

Piaget: Preoperational Thought

Early childhood is the time of preoperational intelligence, the second of Piaget’s four periods of cognitive development (described in Table 2.3 on p. 49). He called early-

Preoperational children are no longer in the stage of sensorimotor intelligence because they can think in symbols, not just via senses and motor skills. In symbolic thought, an object or word can stand for something else, including something out of sight or imagined. Language is the most apparent example of symbolic thought, because using words makes it possible to think about many more things at once. However, although vocabulary and imagination can soar in early childhood, logical connections between ideas are not yet active, not yet operational.

The word dog, for instance, is at first only the family dog sniffing at the child, not yet a symbol (Callaghan, 2013). By age 2, the word becomes a symbol: It can refer to a remembered dog, or a plastic dog, or an imagined dog. Symbolic thought allows for the language explosion (detailed later in this chapter), which enables children to talk about thoughts and memories. However, since thought during these years is preoperational, it is hard for young children to understand the historical connections, similarities, and differences between dogs and wolves, or even between a Labrador retriever and a poodle.

Symbolic thought helps explain animism, the belief of many young children that natural objects (such as a tree or a cloud) are alive and that nonhuman animals have the same characteristics as the child.

Many children’s stories include animals or objects that talk and listen (Aesop’s fables, Winnie-

Obstacles to Logic

Piaget described symbolic thought as characteristic of preoperational thought. He noted four limitations that make logic difficult until about age 6: centration, focus on appearance, static reasoning, and irreversibility.

Centration is the tendency to focus on one aspect of a situation to the exclusion of all others. Young children may, for example, insist that Daddy is a father, not a brother, because they center on the role that he fills for them. The daddy example illustrates a particular type of centration that Piaget called egocentrism—literally, “self-

Egocentrism is not selfishness. One 3-

A second characteristic of preoperational thought is a focus on appearance to the exclusion of other attributes. For instance, a girl given a short haircut might worry that she has turned into a boy. In preoperational thought, a thing is whatever it appears to be—

Third, preoperational children use static reasoning. They believe that the world is stable, unchanging, always in the state in which they currently encounter it. Many children cannot imagine that their own parents were ever children. If they are told that Grandma is their mother’s mother, they still do not understand how people change with maturation.

Especially for Nutritionists How can Piaget’s theory help you encourage children to eat healthy foods?

Take each of the four characteristics of preoperational thought into account. Because of egocentrism, having a special place and plate might assure the child that this food is exclusively his or hers. Since appearance is important, food should look tasty. Since static thinking dominates, if something healthy is added (e.g., grate carrots into the cake, add milk to the soup), do it before the food is given to the child. In the reversibility example in the text, the lettuce should be removed out of the child’s sight and the “new” hamburger presented.

One preschooler wanted his grandmother to tell his mother to never spank him because “she has to do what her mother says.” Often a preschooler whose baby brother or sister sucks a bottle wants a bottle, too. The answer, “You had a bottle when you were little, now you are a big kid,” is not convincing.

The fourth characteristic of preoperational thought is irreversibility. Preoperational thinkers fail to recognize that reversing a process sometimes restores whatever existed before. A young girl might cry because her mother put lettuce on her sandwich. Overwhelmed by her desire to have things “just right,” she might reject the food even after the lettuce is removed because she believes that what is done cannot be undone.

Conservation and Logic

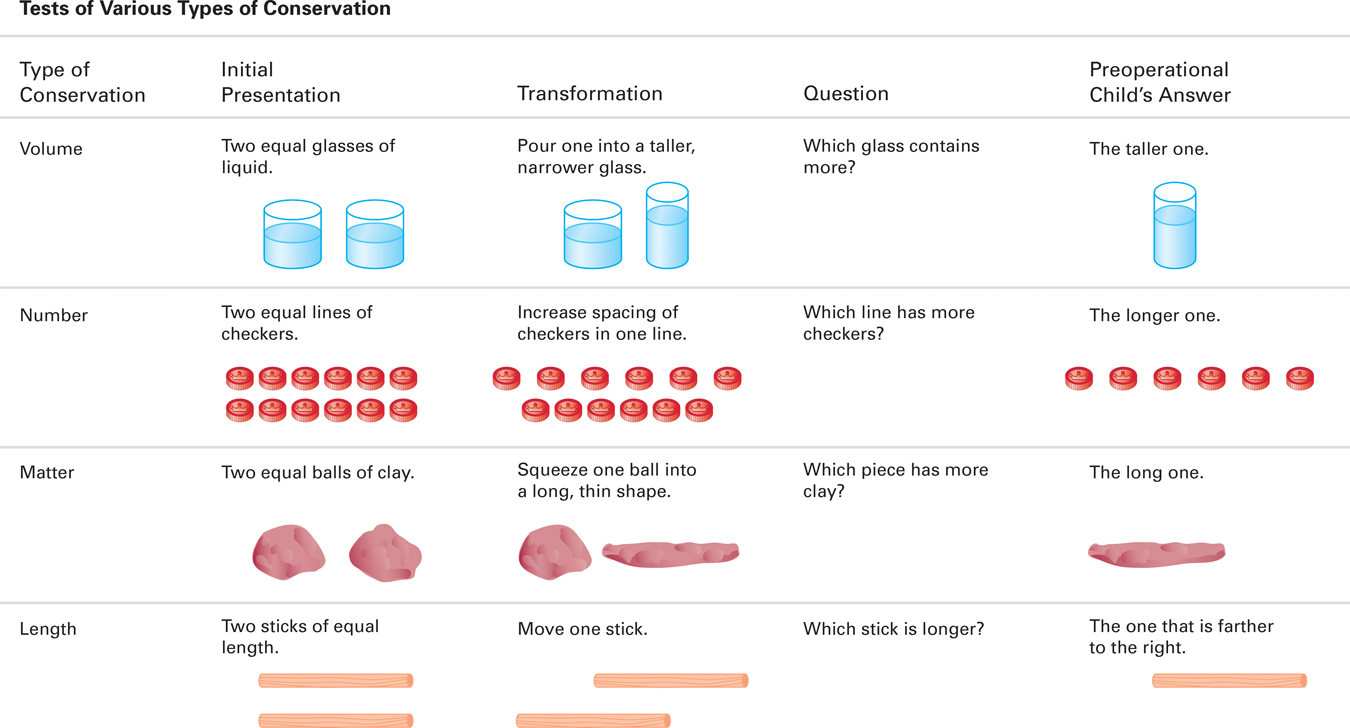

Piaget highlighted several ways in which preoperational intelligence disregards logic. A famous set of experiments involved conservation, the notion that the amount of something remains the same (is conserved) despite changes in its appearance.

Suppose two identical glasses contain the same amount of pink lemonade, and the liquid from one of these glasses is poured into a taller, narrower glass. If young children are asked whether one glass contains more or, alternatively, both glasses contain the same amount, they will insist that the narrower glass (with the higher level) has more. (See Figure 9.1 for other examples.)

Conservation According to Piaget, until children grasp the concept of conservation at (he believed) about age 6 or 7, they cannot understand that the transformations shown here do not change the total amount of liquid, checkers, clay, and wood.

All four characteristics of preoperational thought are evident in this mistake. Young children fail to understand conservation because they focus (center) on what they see (appearance), noticing only the immediate (static) condition. It does not occur to them that they could reverse the process and recreate the level of a moment earlier (irreversibility).

Piaget’s original tests of conservation required children to respond verbally to an adult’s questions. Later research has found that when the tests of logic are simplified or made playful, young children may succeed. In many ways, children indicate via eye movements or gestures that they know something before they can say it in words (Goldin-

As with sensorimotor intelligence in infancy, Piaget underestimated what preoperational children could understand. Piaget was right that young children are not as logical as older children, but he did not realize how much they could learn.

Brain scans, video responses measured in milliseconds, and the computer programs that developmentalists now use were not available to him. Studies from the past 20 years show intellectual activity before age 6 that was not previously understood; they also show that Piaget was perceptive about many aspects of cognition (Crone & Ridderinkhof, 2011).

Given the new data, it is easy to criticize Piaget. However, many adults make the same mistakes. For instance, the shapes of boxes and bottles in the grocery store make it hard to compare volume visually and so undermine adults’ sense of conservation—

Indeed, many adults in the United States encourage children to believe in Santa Claus, the Tooth Fairy, and so on. If we consider preschoolers foolish to imagine that animals and plants have human traits, how should we judge ourselves if we talk to our pets or mourn the death of a tree? When adults say, “Nothing ever changes,” or, “He can never be trusted,” is that static reasoning?

Video Activity: Achieving Conservation focuses on the changes in thinking that make it possible for older children to pass Piaget’s conservation-

A review of the research finds that children are “naïve skeptics … as likely to doubt as to believe” (Woolley & Ghossainy, 2013, p. 1496). They use their best judgment and most reliable sources to decide what is true. Adults are often more skeptical than young children because they have more experience, but they also believe in things not seen (from germs to heaven) because other adults whom they trust (scientists or clergy, depending on specifics) say such unseen things exist.

Preschoolers also rely on their own experience and on trusted sources, but their social network is more limited. Consequently, they rely heavily on their parents and on rules governing behavior (Lane & Harris, 2014). Because of their cognitive limits, smart 3-

a case to study

Stones in the Belly

As we were reading a book about dinosaurs, 3-

I was amazed, never having known this before.

“I didn’t know that dinosaurs ate stones,” I said.

“They don’t eat them.”

“Then how do they get the stones in their bellies? They must swallow them.”

“They don’t eat them.”

“Then how do they get in their bellies?”

“They are just there.”

“How did they get there?”

“They don’t eat them,” said Caleb. “Stones are dirty. We don’t eat them.”

I dropped it, but my question apparently puzzled him. Later he asked his mother, “Do dinosaurs eat stones?”

“Yes, they eat stones so they can grind their food,” she answered.

At that, Caleb was quiet.

In all of this, preoperational cognition is evident. Caleb is bright; he can name several kinds of dinosaurs, as can many young children.

But logic eludes Caleb. He is preoperational, not operational.

It seemed obvious to me that dinosaurs must have swallowed the stones. However, in his static thinking, Caleb said the stones “are just there.” In thinking that is typical of egocentrism, he rejects the thought that they ate them, because he has been told that stones are too dirty to eat.

He is egocentric, reasoning from his own experience, and animistic, in that he thinks animals would not eat stones because he does not. Caleb has no personal experience with dinosaurs, but my question made him think. He trusts his mother, who told him never to eat stones, or, for that matter, sand from the sandbox, or food that fell on the floor. If anyone told him he could eat those things they would seem foolish, as I seemed when I said dinosaurs might eat stones. He did not accept my authority: The implications of the fact that I am his mother’s mother are beyond his static thinking.

But, like many young children, Caleb is curious, and my question raised his curiosity. He consulted his authority, my daughter.

Should I have expected him to tell me that I was right, when his mother agreed with me? No. That would have required far more understanding of reversibility and far less egocentrism than most young children can muster.

Vygotsky: Social Learning

For decades, the magical, illogical, and self-

Vygotsky emphasized another side of early cognition—

Mentors

Vygotsky believed that cognitive development is embedded in a social context at every age (Vygotsky, 1934/1987). He stressed that children are curious and observant. They ask questions—

As you remember from Chapter 2, children learn through guided participation, as mentors teach them. Parents are their first guides, although children are guided by many others, too.

According to Vygotsky, children learn because their mentors do the following:

Present challenges.

Offer assistance (without taking over).

Add crucial information.

Encourage motivation.

OBSERVATION QUIZ What three sociocultural factors make it likely that the child pictured above will learn?

Motivation (this father and son are from Spain, where yellow running shoes are popular), human relationships (note the physical touching of father and son), and materials (the long laces make tying them easier).

Overall, the ability to learn from mentors indicates intelligence; according to Vygotsky, “What children can do with the assistance of others might be in some sense even more indicative of their mental development than what they can do alone” (Vygotsky, 1980, p. 85).

Scaffolding

Vygotsky believed that all individuals learn within their zone of proximal development (ZPD), an intellectual arena in which new ideas and skills can be mastered. Proximal means “near,” so the ZPD includes the ideas children are close to understanding and the skills they can almost master, but are not yet able to demonstrate independently. How and when children learn depends, in part, on the wisdom and willingness of mentors to provide scaffolding, or temporary sensitive support, to help them within their developmental zone. (Developmental Link: The ZPD is discussed in Chapter 2.)

Good mentors provide plenty of scaffolding, encouraging children to look both ways before crossing the street (while holding the child’s hand) or letting them stir the cake batter (perhaps while covering the child’s hand on the spoon handle, in guided participation). Crucial in every activity is joint engagement, when both learner and mentor are actively involved together in the learning zone (Adamson et al., 2014).

OBSERVATION QUIZ Is the girl below right-

Right–

As always, cultural differences are crucial. Consider book reading, for instance, an activity parents worldwide do with their young children, in part because it fosters language, reading, and moral development. When an adult reads to children, the adult scaffolds—

By contrast, book reading in low-

Overimitation

Sometimes scaffolding is inadvertent, as when children observe something said or done and then try to do likewise—

More benignly, children imitate habits and customs that are meaningless, a trait called overimitation, evident in humans but rare in other animals. This stems from the child’s eagerness to learn from mentors, allowing “rapid, high-

Overimitation was demonstrated in a series of experiments with 3-

Especially for Driving Instructors Sometimes your students cry, curse, or quit. How would Vygotsky advise you to proceed?

Use guided participation to scaffold the instruction so that your students are not overwhelmed. Be sure to provide lots of praise and days of practice. If emotion erupts, do not take it as an attack on you.

In part of the study, some children one-

Other children did not see the demonstration. When they were given the stick and asked to open the box, they simply pulled the knob. Then they observed an adult do the stick-

Apparently, children everywhere learn from others through observation, even if they have not been taught to do so. They even learn to do things contrary to their prior learning. Thus, scaffolding occurs through observation as well as explicit guidance. Across cultures, overimitation is striking and even generalizes to other similar situations. Children everywhere are strongly inclined to learn whatever adults from their culture do (Nielsen et al., 2014).

That is exactly what Vygotsky expected and explained. Curiously, young children are not adept at figuring out new ways to use various tools (Nielsen et al., 2014). Young children’s minds are quick to imitate what adults do, but slow to figure out creative ways to accomplish their goals. That innovative ability, apparently, must wait until more cognitive maturation has occurred.

Language as a Tool

Although all the objects of a culture guide children, Vygotsky believed that words are especially pivotal. He thought language advances thinking in two ways (Fernyhough, 2010). The first way is with internal dialogue, or private speech, in which people talk to themselves (Vygotsky, 2012). Young children use private speech often. They talk aloud to review, decide, and explain events to themselves (and, incidentally, to anyone else within earshot) (Al-

Older preschoolers are more selective, effective, and circumspect, sometimes whispering. Audible or not, private speech aids cognition and self-

The second way in which language advances thinking, according to Vygotsky, is by mediating the social interaction that is vital to learning (Vygotsky, 2012). This social mediation function of speech occurs during both formal instruction (when teachers explain things) and casual conversation.

Words entice people into the zone of proximal development, as mentors guide children to learn numbers, recall memories, and follow routines. Indeed, children who count out loud and use other aspects of private speech to help them with numbers are likely to advance in mathematical understanding.

STEM Learning

A practical use of Vygotsky’s theory concerns the current emphasis on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) education. Because finding more young people to specialize in those fields is crucial for economic growth, educators and political leaders are continually seeking ways to make STEM fields attractive to adolescents and young adults of all ethnicities (Rogers-

Research on early childhood suggests that STEM education actually begins long before high school. This is increasingly recognized by experts, who note that most parents and teachers have much to learn about math and science if they wish to teach these subjects to young children (Hong et al., 2013; Bers et al., 2013).

For example, learning about numbers is possible very early in life. Even babies have a sense of whether one, two, or three objects are in a display, although exactly what infants understand about numbers is controversial (Varga et al., 2010). If Vygotsky is correct that words are tools, toddlers need to hear number words and science concepts early (not just counting and shapes, but fractions and science principles, such as the laws of motion) so that other knowledge becomes accessible. In math understanding, it is evident that preschoolers gradually learn to

Count objects, with one number per item (called one-

to- ).one correspondence Remember times and ages (bedtime at 8, a child is 4 years old, and so on).

Understand sequence (first child wins, last child loses).

Know what numbers are higher than others. (It is not obvious to young children that 7 is greater than 4.)

These and many other cognitive accomplishments of young children have been the subject of extensive research: Mentoring and language are always found to be pivotal.

Especially in math, computers can promote a dialogue that helps contemporary young children learn. Educational software becomes “a conduit for collaborative learning” (Cicconi, 2014, p. 58) as Web 2.0 programs respond to the particular abilities and needs of the learner.

OBSERVATION QUIZ Could this photo have been taken 10 years ago?

No. Each child has a tablet–

Often in preschool classrooms with interactive education, two or three children work together, each mentoring the other, talking aloud as the computer prompts them. This can occur at home, too: Educators frown on using a computer screen as a substitute for human interaction, but they sometimes consider it an adjunct to promote learning, just as a book might be (Alper, 2013).

Culture affects language, which in turn fosters math knowledge. For example, English-

German-

By age 3 or 4, children’s brains are mature enough to comprehend numbers, store memories, and recognize routines. Whether or not children actually demonstrate such understanding depends on what they hear and how they participate in various activities within their families, schools, and cultures.

Some 2-

Children’s Theories

Piaget and Vygotsky both recognized that children work to understand their world. No contemporary developmental scientist doubts that. How do children acquire their impressive knowledge? Part of the answer is that children do more than gain words and concepts; they develop theories to help them understand and remember—

Theory-Theory

Humans of all ages want explanations. Theory-

search for causal regularities in the world around us. We are perpetually driven to look for deeper explanations of our experience, and broader and more reliable predictions about it…. Children seem, quite literally, to be born with … the desire to understand the world and the desire to discover how to behave in it.

[Gopnik, 2001, p. 66]

According to theory-

Exactly how do children seek explanations? They ask questions, and, if they are not satisfied with the answers, they develop their own theories. This is particularly evident in children’s understanding of God and religion. One child thought his grandpa died because God was lonely; another thought thunder occurred because God was rearranging the furniture.

Theories do not appear randomly. Children wonder about the underlying purpose of whatever they observe, and in order to develop a theory about what causes what and why, they note how often a particular event occurs. They follow the same processes that scientists do: asking questions, developing hypotheses, gathering data, and drawing conclusions.

Of course, a child’s method of understanding and interpreting experience lacks the rigor of scientific experiments, but questions of physics, biology, and the social sciences are explored: “infants and young children not only detect statistical patterns, they use those patterns to test hypotheses about people and things” (Gopnik, 2012, p. 1625). Their conclusions are not always correct: Like all good scientists, they allow new data to promote revision.

For instance, when I was a young child, I noticed that my father never carried an umbrella. Since I looked up to him, I assumed he must have had a good reason. Neither did my brother, which confirmed for me that my father was right. Consequently, throughout all my adult years, I never carried an umbrella.

Over time I developed many reasons for my father’s behavior. He must have realized, I decided, that umbrellas poke people in the eye, get forgotten, blow away, and are lost. Then, when Dad was in his 80s, my brother asked him why he didn’t like umbrellas. The answer stunned me: “Chamberlain.”

Neville Chamberlain was famous for carrying an umbrella when he was prime minister of England from 1937 to 1940. He was photographed with his black umbrella after signing the Munich Agreement in 1938, when he mistakenly and naively announced that Hitler would not attack England. For Dad, umbrellas symbolized foolish trust and he said that no political leader would dare carry an umbrella. I had constructed a theory to justify something I observed. That is theory-

In the egocentrism of early childhood, preschoolers theorize that everyone operates as they themselves do, which makes them more aware of situational differences than personality differences. For instance, each child knows that he or she acts differently, say, in a familiar playground on a sunny day than on an unfamiliar street in a thunderstorm. Context is crucial, but the child is the same person in both situations.

That explains the results of a series of experiments in which children observe that one puppet refuses to play on a trampoline or ride a bicycle and another puppet does both. Four-

One common theory-

This is an example of a general principle: Children theorize about intentions before they imitate what they see. As you have read, when children saw an adult wave a stick before opening a box, the children theorized that, since the adult did it deliberately, stick-

Theory of Mind

Mental processes—

To know what goes on in another’s mind, people develop a folk psychology, which includes ideas about other people’s thinking, called theory of mind. Theory of mind is an emergent ability, slow to develop but typically beginning in most children at about age 4 (Carlson et al., 2013). Some aspects of theory of mind develop sooner than age 4, and some later. However, longitudinal research finds that the preschool years typically begin with 2-

Generally, realizing that thoughts do not mirror reality is beyond very young children, but that realization dawns on them sometime after age 3. It then occurs to them that people can be deliberately deceived or fooled—

Especially for Social Scientists Can you think of any connection between Piaget’s theory of preoperational thought and 3-

According to Piaget, preschool children focus on appearance and on static conditions (so they cannot mentally reverse a process). Furthermore, they are egocentric, believing that everyone shares their point of view. No wonder they believe that they had always known the puppy was in the blue box and that Max would know that, too.

In one of dozens of false-

The development of theory of mind can be seen when young children try to escape punishment by lying. Their face often betrays them: worried or shifting eyes, pursed lips, and so on. Parents sometimes say, “I know when you are lying,” and, to the consternation of most 3-

Video: Theory of Mind: False-Belief TasksAMI PARIKH/SHUTTERSTOCK

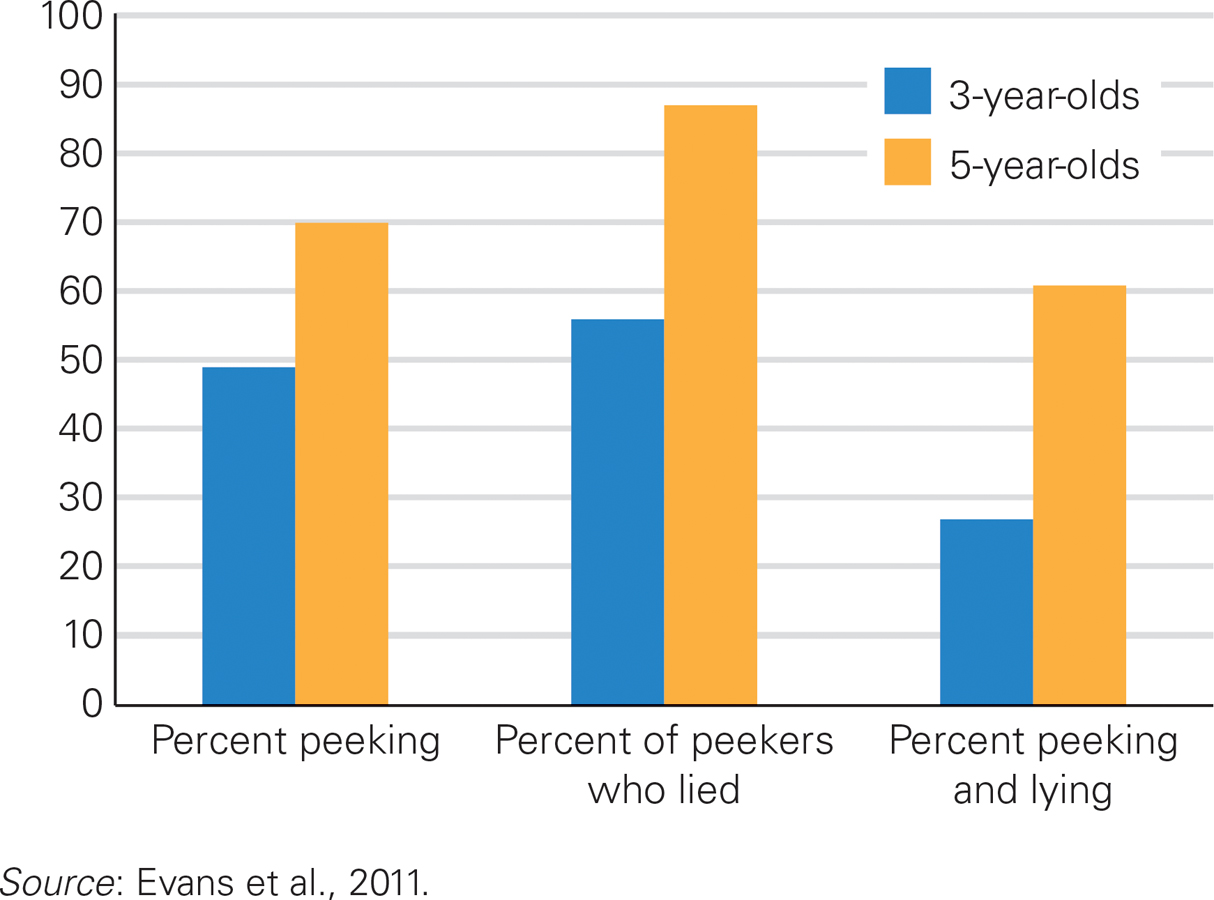

In one experiment, 247 children, aged 3 to 5, were left alone at a table that had an upside-

The rest lied, and their skill increased with their age. The 3-

This particular study was done in Beijing, China, but the results seem universal: Older children are better liars. Beyond the age differences, the experimenters found that the more logical liars were also more advanced in theory of mind and executive functioning (Evans et al., 2011), which indicates a more mature prefrontal cortex (see Figure 9.2).

Better with Age? Could an obedient and honest 3-

Of course, many egocentric children convince themselves that something is true when it is not—

a view from science

Witness to a Crime

One application of early cognitive competency has received attention among lawyers and judges. Children may be the only witnesses to crimes, especially of sexual abuse or domestic violence. Can a young child’s words be trusted? Adults have gone to both extremes in answering this question. As one legal discussion begins:

Perhaps as a result of the collective guilt caused by disbelieving the true victims of this abuse, in recent years the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction, to an unwavering conviction that a young child is incapable of fabricating a story of abuse, even when the tale of mistreatment is inherently incredible.

[Shanks, 2011]

The answer to the question, “Is child testimony accurate?” is: “Sometimes.” In recent years, psychologists have shown that people of all ages misremember (Frenda et al., 2011; Lyons et al., 2010) and that each age group misremembers in particular ways.

Younger children, not yet imbued with stereotypes, are sometimes more accurate than older witnesses who are influenced by prejudice (Brainerd et al., 2008), but they may confuse time, place, person, and action—

Words and expressions can plant false ideas in young children’s minds, either deliberately (as an abuser might) or inadvertently (as a fearful parent might). Children’s shaky grasp of reality makes them vulnerable to scaffolding memories that are imagined, not experienced (Bruck et al., 2006). This happened tragically 35 years ago in many jurisdictions, when adults suddenly realized that small children could be sexually abused and then decided that sexual abuse was rampant in preschools.

For instance, 3-

Young children are not necessarily worse than adults at recounting experiences if they are interviewed with open-

With sexual abuse in particular, a child might believe that some lewd act is OK if an adult says so. Only years later does the victim realize that it was abuse. Research on adult memory finds that sometimes adults reinterpret what happened to them, with genuine memories of experiences that were criminal. However, people of all ages sometimes believe that an event, including abuse, occurred when it did not (Geraerts et al., 2009).

This knowledge provides guidelines for police officers, social workers, judges, teachers, and parents. When children are witnesses, they should simply be asked to tell what happened, perhaps with eyes closed to reduce their natural attempt to please (Kyriakidou et al., 2014). If, instead, an adult says, “Did he touch you there?” a child might say yes if he thinks that is what the adult wants to hear. Preschoolers’ cognition is a mix of egocentric fantasy, social influence, and innocent honesty—

Brain and Context

Many studies have found that a child’s ability to develop theories correlates with neurological maturation, which also correlates with advances in executive processing—

Evidence for the crucial role of brain maturation comes from the other research on the same 3-

The children needed to inhibit their automatic reaction, and the ability to do this indicates advanced executive function, which correlates with maturation of the prefrontal cortex. Even when compared to other children who were the same age, those who failed the day–

Does the crucial role of neurological maturation make context irrelevant? No: Nurture is always important. For instance, research finds that language development fosters theory of mind, especially when mother–

As brothers and sisters argue, agree, compete, and cooperate, and as older siblings fool younger ones, it dawns on 3-

SUMMING UP Preoperational children, according to Piaget, can use symbolic thought but are illogical and egocentric, limited by the appearance of things and by their immediate experience. Their egocentrism occurs not because they are selfish, but because their minds are immature. Vygotsky realized that children are powerfully influenced by their social contexts, including their mentors and the cultures in which they live. In their zone of proximal development, children are ready to move beyond their current understanding, especially if deliberate or inadvertent scaffolding occurs.

Children use their cognitive abilities to develop theories about their experiences, as is evident in theory-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 9.1

What are the strengths of preoperational thought?

Symbolic thought allows a child to become much more adept at pretending and to refer to things not seen. Symbolic thought enables the language explosion, since children can now talk about what they think, imagine, and remember. Piaget underestimated cognition during early childhood. He relied on words spoken in an experimental setting rather than nonverbal signs in play content. There are thinking errors that are typical of the preoperational stage, which weaken the child's ability to make accurate judgments. For example, centration causes children to focus on one aspect of a situation, excluding other aspects. A specific type of centration is egocentrism (assessing the world exclusively from their own perspective). They also focus on appearance (short hair means the child is a boy), static reasoning (Mommy has always been an adult), and irreversibility (removing the lettuce from the sandwich does not fix the problem that there was lettuce on the sandwich).Question 9.2

What is the difference between egocentrism in a child and selfishness in an adult?

A child's egocentrism is not selfishness. It is the child's inability to see life from anyone's perspective but his or her own. An egocentric child can be very generous, often giving elaborate gifts chosen with care. Unfortunately, the gifts represent the child's interests instead of the receiver's. Selfishness in an adult focuses on ignoring other people's reasonable needs in favor of pursuing one's own self–interest. An adult might give a gift that represents his or her own interests in the hope that the receiver will just give the gift back. The egocentric child would be disappointed if the receiver gave the gift back. Question 9.3

How does guided participation increase a child’s zone of proximal development?

The zone of proximal development is an intellectual arena in which new ideas and skills can be mastered. Guided participation allows children to expand the zone of ideas that they can almost understand and skills that they can almost master because their mentors provide scaffolding as they present challenges, offer assistance without taking over, add crucial information, and encourage motivation.Question 9.4

Why did Vygotsky think that talking to oneself is not a sign of illness but an aid to cognition?

According to Vygotsky, children talk aloud to review, decide, and explain events to themselves, as well as to mediate social interaction that is vital to learning and cognitive development.Question 9.5

What factors spur the development of theory of mind?

A person's theory of mind refers to his or her theory of what other people might be thinking. The development of theory of mind correlates with a maturing prefrontal cortex. Other contributing factors include language development, the presence of an older sibling, and culture and context. The main criterion for having a theory of mind is an awareness that other people may not be thinking the same thoughts that you are, which usually occurs around age 4.