Language Learning

Learning language is the premier cognitive accomplishment of early childhood. Two-

A Sensitive Time

Video Activity: Language Acquisition in Young Children features video clips of a new sign language created by deaf Nicaraguan children and provides insights into how language evolves.

Brain maturation, myelination, scaffolding, and social interaction make early childhood ideal for learning language. As you remember from Chapter 1, scientists once thought that early childhood was a critical period for language learning—

It is easy to understand why they thought so. Young children have powerful motivation and ability to sort words and sounds into meaning (theory-

Instead, early childhood is a sensitive period for language learning—

Exactly how sensitive the preschool years are is still disputed (DeKeyser, 2013). There is no doubt that it is easier to learn a first or second language earlier than later, nor is there any doubt that some people learn a second language in adulthood. Adult language learning is harder, but not impossible.

Preoperational thinking—

Asa is not alone. One of the valuable (and sometimes frustrating) traits of young children is that they talk about many things to adults, to each other, to themselves, to their toys—

The Vocabulary Explosion

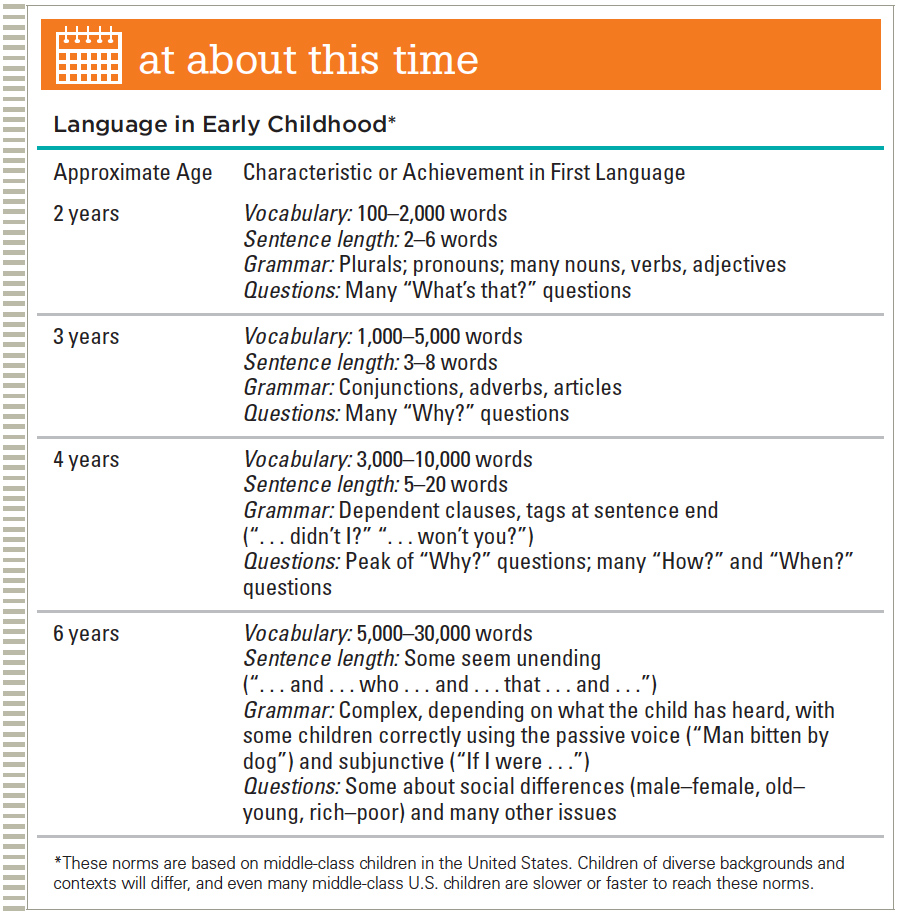

The average child knows about 500 words at age 2 and more than 10,000 at age 6 (Herschensohn, 2007). That’s more than six new words a day. These are averages. Estimates of vocabulary size at age 6 vary from 5,000 to 30,000: Some children learn six times as many words as others. Always, however, vocabulary builds quickly, and comprehension is more extensive than speech.

It is not always easy to know how many words a child understands, in part because some tests of vocabulary are more stringent than others (Hoffman et al., 2013). For example, after children listened to a book about a raccoon that saw its reflection in the water, they were asked what “reflection” means. Here are five answers:

“It means that your reflection is yourself. It means that there is another person that looks just like you.”

“Means if you see yourself in stuff and you see your reflection.”

“Is like when you look in something, like water, you can see yourself.”

“It mean your face go in the water.”

“That means if you the same skin as him, you blend in.” (Hoffman et al., 2013, pp. 13–

14)

Which of these five children knows the vocabulary word? The correct answer to that question could be none, all, or some number in between.

In another example, when a story included “a chill ran down his spine,” children were asked what chill meant. One child answered, “When you want to lay down and watch TV—

Fast-Mapping

After painstakingly learning one word at a time between 12 and 18 months of age, children develop interconnected categories for words, a kind of grid or mental map that makes speedy vocabulary acquisition possible. Each of the children above answered the question: They thought they knew the word, and they sort of did.

Learning a word after one exposure is called fast-

Language mapping is not precise. For example, children rapidly connect new animal names close to already-

All preschoolers can fast map words, but some children are quicker than others, and some words are easier than others. A study that tested young children’s ability to fast-

Picture books offer many opportunities to advance vocabulary through scaffolding and fast-

This process explains children’s learning of color words. Generally, 2-

Thus, all women may be called mothers, all cats can be kitties, and all bright colors red. As one team of scientists explains, adult color words are the result of slow-

Words and the Limits of Logic

Closely related to fast-

Bilingual children who don’t know a word in the language they are speaking often insert a word from the other language, code-

To call it “Spanglish” when a Spanish-

Some English words are particularly difficult for every child to use correctly—

Extensive study of children’s language abilities finds that fast-

Acquiring Grammar

Remember from Chapter 6 that grammar includes structures, techniques, and rules that communicate meaning. Knowledge of grammar is essential for learning to speak, read, and write. A large vocabulary is useless unless a person knows how to put words together. Each language has its own grammar rules; that’s one reason children speak in one-

Brain and Basics

By age 2, children understand the basics. For example, English-

Children apply rules of grammar as soon as they figure them out, using their own theories about how language works and their experience regarding when and how often various rules apply (Meltzoff & Gopnik, 2013). For example, English-

Soon they add an s to make the plural of words they have never heard before, even nonsense words. If preschoolers are shown a drawing of an abstract shape, told it is called a wug, and are then shown two of these shapes, they say there are two wugs. Children realize words have a singular and a plural before they use that grammar form themselves (Zapf & Smith, 2007).

One reason for variation in particulars of language learning is that several parts of the brain are involved, each myelinating at a distinct rate. Furthermore, many genes and alleles affect comprehension and expression. In general, genes affect expressive (spoken or written) language more than receptive (heard or read) language. Thus, some children are relatively talkative or quiet because they inherit that tendency, but experience (not genes) determines what they understand. For that, parents and teachers are crucial.

Grammar Mistakes

Sometimes children apply the rules of grammar when they should not. This error is called overregularization. By age 4, many children overregularize that final s, talking about foots, tooths, and mouses. This signifies knowledge, not stupidity: Many children first say words correctly (feet, teeth, mice), repeating what they have heard. Later, they are smart enough to apply the rules of grammar, and overregularize, assuming that all constructions follow the rules (Ramscar & Dye, 2011). The child who says, “I goed to the store” needs to hear, “Oh, you went to the store?” rather than criticism.

More difficult to learn is an aspect of language called pragmatics—knowing which words, tones, and grammatical forms to use with whom (Siegal & Surian, 2012). In some languages, it is essential to know which set of words to use when a person is older or not a close friend or family member.

For example, French children learn the difference between tu and vous in early childhood. Although both words mean “you,” tu is used with familiar people, while vous is the more formal expression (as well as the plural expression). In other languages, children learn that there are two words for grandmother, depending on whose mother she is.

English does not make those distinctions, but pragmatics is important for early-

Knowledge of pragmatics is evident when a 4-

Learning Two Languages

Language-

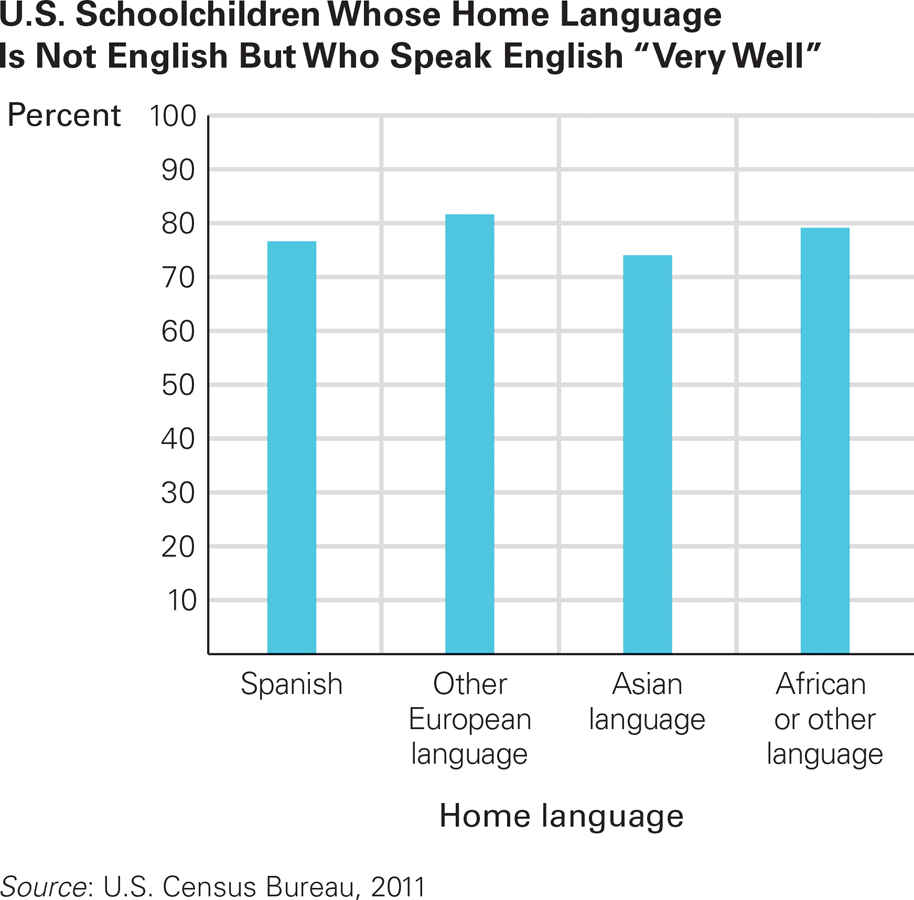

In the United States in 2011, 22 percent of schoolchildren spoke a language other than English at home, with most of them (77 percent) also speaking English well, according to their parents (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011) (see Figure 9.3). The percentage of bilingual children is higher in many other nations. In many African, Asian, and European nations, by sixth grade most schoolchildren are bilingual, and some are trilingual.

Mastering English: The Younger, the Better Of all the schoolchildren whose home language is not English, this is the proportion who, according to their parents, speak English well. Immigrant children who attend school almost always master English within five years.

How and Why

Unlike a century ago, everyone now seeking U.S. citizenship must be able to speak English. Some people believe that national unity is threatened by language-

Should a nation have one official language, several, or none? Individuals and nations have divergent answers. Switzerland has three official languages; Canada has two; India has one national language (Hindi), but many states of India also have their own, for a total of 28 official languages; the United States has none.

Some adults fear that young children who are taught two languages might become semilingual, not bilingual, “at risk for delayed, incomplete, and possibly even impaired language development” (Genesee, 2008, p. 17). Others have used their own experience to argue the opposite, that “there is absolutely no evidence that children get confused if they learn two languages” (Genesee, 2008, p. 18).

This second position has much more research support. Soon after the vocabulary explosion, children who have heard two languages since birth usually master two distinct sets of words and grammar, along with each language’s pauses, pronunciations, intonations, and gestures. Proficiency is directly related to how much language they hear (Hoff et al., 2012).

Early childhood is the best time to learn languages. Neuroscience finds that for adults who mastered two languages when they were young, both languages are located in the same areas of the brain with no impact on the cortex structure (Klein et al., 2014). They manage to keep the two languages separate, activating one and temporarily inhibiting the other when speaking to a monolingual person. They may be a millisecond slower to respond when they must switch languages, but their brains function better overall. Being bilingual benefits the brain lifelong, further evidence for plasticity. Indeed, the bilingual brain may provide some resistance to Alzheimer’s dementia in old age (Costa & Sebastián-

Learning a “foreign” language in high school or college, as required of most U.S. children, is too late for fluency. After childhood, the logic of language is possible to grasp, so adults can learn the rules of forming the past tense, for instance. However, pronunciation, idioms, and exceptions to the rules are confusing and rarely mastered after puberty. The human brain is designed to learn language best in childhood.

Do not equate pronunciation and spoken fluency with comprehension and reading ability. Many adults who speak the majority language with an accent are nonetheless proficient in the language and culture (difference is not deficit). From infancy on, hearing is more acute than vocalization. Almost all young children mispronounce whatever language they speak, blithely unaware of their mistakes.

For example, almost all young children transpose sounds (magazine becomes mazagine), drop consonants (truck becomes ruck), convert difficult sounds to easier ones (father becomes fadder), and drop complex sounds (cherry become terry). Mispronunciation does not impair fluency primarily because young children are more receptive than expressive—

Language Loss and Gains

Schools in all nations stress the dominant language, sometimes exclusively. Consequently, language-

Some language-

No shift is inevitable: The attitudes and practices of parents and the community are crucial. Another crucial aspect is cohort, as shown by a multi-

Remember that young children are preoperational: They center on the immediate status of their language (not on future usefulness or past glory), on appearance more than substance. No wonder many shift toward the language of the dominant culture.

Since language is integral to culture, if a child is to become fluently bilingual, everyone who speaks with the child should show appreciation of both cultures, and children need to hear twice as much talk as usual (Hoff et al., 2012). If the parents do not speak the majority language, they benefit their child’s learning by talking, listening, and playing with the child extensively in the home language. Learning one language well makes it easier to learn another (Hoff et al., 2014).

Especially for Immigrant Parents You want your children to be fluent in the language of your family’s new country, even though you do not speak that language well. Should you speak to your children in your native tongue or in the new language?

Children learn by listening, so it is important to speak with them often. Depending on how comfortable you are with the new language, you might prefer to read to your children, sing to them, and converse with them primarily in your native language and find a good preschool where they will learn the new language. The worst thing you could do would be to restrict speech in either tongue.

The same practices can make a child fluently trilingual, as some 5-

The extent of exposure is crucial: Unfortunately it is typical for one parent to speak with the child much less than the other, and the child’s language learning reflects that deficit (MacLeod et al., 2013). If a young child is immersed in three languages, he or she may speak all three without an accent—

Listening, Talking, and Reading

Because understanding the printed word is crucial, a meta-

Code-

focused teaching. In order for children to read, they must “break the code” from spoken to written words. It helps if they learn the letters and sounds of the alphabet (e.g., “A, alligators all around” or, conventionally, “B is for baby”).Book reading. Vocabulary as well as familiarity with pages and print will increase when adults read to children, allowing questions and conversation.

Parent education. When teachers and other professionals teach parents how to stimulate cognition (as in book reading), children become better readers. Adults need to use words to expand vocabulary. Unfortunately, too often adults use words primarily to control (“don’t touch”; “stop that”), not to teach.

Language enhancement. Within each child’s zone of proximal development, mentors can expand vocabulary and grammar, based on the child’s knowledge and experience.

Preschool programs. Children learn from teachers, songs, excursions, and other children. (We discuss variations of early education next, but every study finds that preschools advance language acquisition.)

SUMMING UP Children learn language rapidly and well during early childhood, with an explosion of vocabulary and mastery of many grammatical constructions. Fast-

Young children can learn two languages almost as easily as one if adults talk frequently, listen carefully, and value both languages. In brain development, children benefit from learning two languages. However, some children whose parents speak a minority language undergo a language shift, abandoning their first language. Others never master a second language because they were not exposed to one during the sensitive time for language learning.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 9.6

What is the evidence that early childhood is a sensitive time for learning language?

Young children are called “language sponges” because they soak up every drop of language they encounter. Language learning is an example of dynamic systems, in that every part of the developmental process influences every other part. To be specific, there are “multiple sensitive periods . . . auditory, phonological, semantic, syntactic, and motor systems, along with the developmental interactions among these components.” All of these facilitate language learning.Question 9.7

How does fast-

mapping aid the language explosion? Children develop an interconnected set of categories for words, a kind of grid or mental map, which makes speedy vocabulary acquisition, or fast–mapping, possible. Rather than figuring out the exact definition after hearing a word used in several contexts, children hear a word once and quickly stick it into a category in their mental language grid. Question 9.8

How does overregularization signify a cognitive advance?

Sometimes children apply the rules of grammar when they should not, an error called overregularization. This is actually evidence of increasing knowledge: Many children first say words correctly (feet, teeth, mice), repeating what they have heard. Later, when they grasp the systematic rules of grammar and try to apply it, they overregularize, assuming that all constructions are regular.Question 9.9

What in language learning shows the limitations of logic in early childhood?

Logical extensions are evidence of the limits of logic. Children learn a word and use it to describe other objects that fall in their same “category.” For example, after learning the word for ketchup, a child may state they had “ketchup soup” at preschool, not knowing the term “tomato soup” and thinking ketchup was a good fit.Question 9.10

What are the advantages of teaching a child two languages?

Neuroscience finds that young bilingual children site both languages in the same areas of their brains yet manage to keep them separate. This separation allows them to activate one language and temporarily inhibit the other, experiencing no confusion when they speak to a monolingual person. They may be a millisecond slower to respond if they must switch languages, but their brains overall function better and may even have some resistance to Alzheimer dementia in old age. Studies show that learning a second language in adulthood usually shows different activation of brain areas, and there is a slower response to the language.Question 9.11

How can the language shift be avoided?

Language–minority parents fear that their children will make a language shift, becoming more fluent in the school language than in their home language which might be forgotten. Since language is integral to culture, if a child is to become fluently bilingual, everyone who speaks with the child should show appreciation of both cultures, and children need to hear twice as much talk as usual. If the parents do not speak the majority language, they benefit their child's learning by talking, listening, and playing with the child extensively in the home language. Learning one language well makes it easier to learn another.