Biosocial Development

Biologically, the years from ages 18 to 25 are prime time for hard physical work and safe reproduction. However, the reality that young adults can carry rocks, plow fields, or haul water is no longer admired, nor is their fertility. If a contemporary young couple had a baby every year, their neighbors would be more appalled than approving. Now, societies, families, and young adults themselves expect more education, later marriage, and fewer children than was the norm a few decades ago.

Strong and Active Bodies

Health has not changed, except maybe to improve. As always, every body -system—

To understand this, it is helpful to understand three aspects of body functioning that keep emerging adults healthy: organ reserve, homeostasis, and allostatic load.

Organ reserve refers to the extra power that every organ can call upon when needed. That reserve power decreases each year, but in emerging adulthood, it usually allows speedy recovery from excess demands on the body, such as exercising for hours, staying awake all night, or drinking too much alcohol.

Closely related to organ reserve is homeostasis—a balance between various body functions that keeps every physical function in sync with every other. For example, if the air temperature rises, people sweat, move slowly, and thirst for cold drinks—

The next time you read about heat-

Related to homeostasis is allostasis, a dynamic body adjustment that gradually changes overall physiology. The main difference between homeostasis and allostasis is time: Homeostasis requires an immediate response from body systems, whereas allostasis refers to long-

The effects of early life are apparent. Organ reserve usually protects emerging adults, because some reserve is used to maintain health. In a measure called allostatic load, daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly adjustments accumulate, gradually affecting the burden, or load, that weighs down health. Few emerging adults reach the threshold that results in serious illness, but health habits early in life are already evident by age 25 in metabolism, weight, lung capacity, cholesterol or so on. Even the nutrition of the mother when she was pregnant affects the fetus, the child, and then the young adult.

For example, how much a person eats is affected by many factors. An empty stomach immediately triggers hormones, stomach pains, low blood sugar, and so on, all of which lead a person to eat again. That is homeostasis. But if a person begins a serious diet, ignoring hunger messages for days and weeks, rapid weight loss soon triggers new homeostatic reactions, allowing the person to function with a reduced calorie intake, which makes it harder to lose more weight (Tremblay & Chaput, 2012).

Over the years, allostasis becomes crucial. If a person overeats or starves day after day, the body adjusts: Appetite increases or decreases accordingly. But continued homeostasis may take a toll on health, increasing the allostatic load. Obesity is one cause of diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, and so on—

Keep Moving

Another example comes from exercise. After a few minutes of exercise, the heart beats faster and breathing becomes heavier—

OBSERVATION QUIZ One detail in the young man’s hands suggests that the setting is Asia, not North America. What is it?

It is the cigarette, not the camera. Most young men in Canada and the United States do not smoke, especially publicly and casually, as this man does.

The opposite is also true. One study (CARDIA—

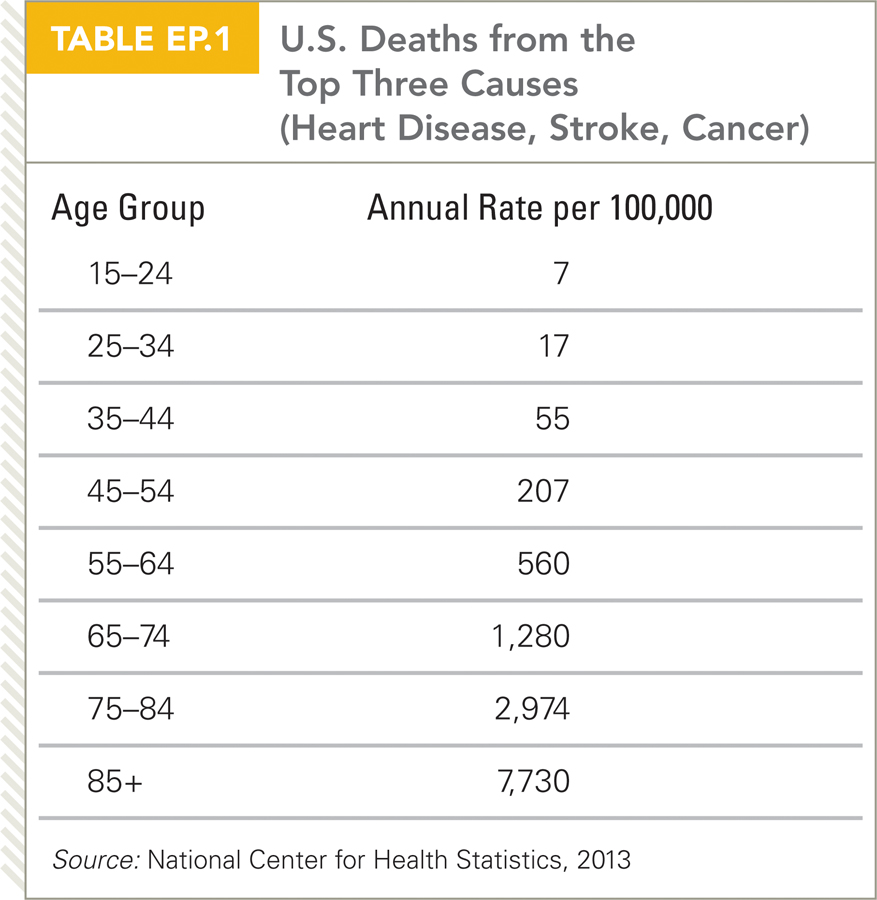

In CARDIA, problems began but were unnoticed (except in blood work) when participants were in their 20s. Organ reserve allowed them to function. Nonetheless, each year their allostatic load increased, unless their daily habits changed (Camhi et al., 2013). By late adulthood, the load is deadly (see Table EP.1).

Fertility, Then and Now

As already mentioned, the sexual-

That has changed dramatically. The bodies of emerging adults still crave sex, but their minds know they are not ready for parenthood. For many, the solution is sex without pregnancy, made possible by modern contraception. The world’s 2010 birth rate for 15-

Taking Risks

Remember that each age group has its own gains and losses, characteristics that can be a blessing or a burden. This is apparent with risk-

Societies as well as individuals benefit because emerging adults take chances. Enrolling in college, moving to a new state or nation, getting married, having a baby—

Yet risk-

Destructive risks that are common in emerging adulthood include unprotected sex with a new partner, driving fast without a seat belt, carrying a loaded gun, abusing drugs, and addictive gambling—

Risky Sex

Premarital sex, while avoiding parenthood, seems a good solution to the conflict between physical and psychological maturation, but it has serious consequences. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are increasing, which may cause lifetime infertility and disease, including some that seem unrelated, such as cancer and tuberculosis.

In earlier times, prostitution was local, which kept STIs local as well. Now, with globalization, an STI caught in one place quickly spreads. Sex-

This proliferation is particularly tragic with HIV/AIDS. Within 30 years, primarily because of the sexual activities of young adults, HIV has become a worldwide epidemic, with more female than male victims (Fan et al., 2014).

Young adults remain the prime STI vectors (those who spread disease) as well as the new victims. Genetic research on DNA and on STIs have proven that the subtypes and recombinations of HIV—

Indeed, tracing HIV in Africa shows that it originally was only in the capital of what now is the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Then it spread following the route of the railroads built as part of modernization: carriers of HIV took the disease to nations where it had not been (Faria et al., 2014). Travel benefits emerging adults in many ways, expanding the mind and fostering cultural understanding, but newcomers introduce diseases, and catch diseases, that were once controlled by local conditions.

Risky Sports

Many young adults enjoy risks in recreation: They climb mountains, swim in oceans, run in pain, play past exhaustion, and so on. Skydiving, bungee jumping, pond swooping, parkour, potholing (in caves), waterfall kayaking, ziplining, and many more activities have been invented to increase excitement. Serious injury is not the goal, but risk adds to the thrill.

Competitive extreme sports (such as motocross—motorcycle jumping off a ramp into “big air,” doing tricks during the fall, and hoping to land upright) are new sports for some emerging adults, who find golf, bowling, and so on too tame (Breivik, 2010).

a case to study

An Adrenaline Junkie

The fact that extreme sports are age-

Four years later, Pastrana set a new record for leaping through big air in an automobile, as he drove over the ocean from a ramp on the California shoreline to a barge more than 250 feet out. He crashed into a barrier on the boat but emerged, seemingly ecstatic and unhurt, to the thunderous cheers of thousands of other young adults on the shore (Roberts, 2010).

In 2011, a broken foot and ankle made him temporarily halt extreme sports—

In 2014, after becoming a husband and a father (twice), he quit NASCAR. He says his most hazardous race days are over. He is an icon for the next generation of daredevil young men.

Drug Abuse

The same impulse that is admired in extreme sports leads to behaviors that are destructive, not only for individuals but for the community. The most studied of these is drug abuse (Reith, 2005).

By definition, drug abuse occurs whenever a drug (legal or illegal, prescribed or not) is used in a harmful way, damaging a person’s physical, cognitive, or psychosocial well-

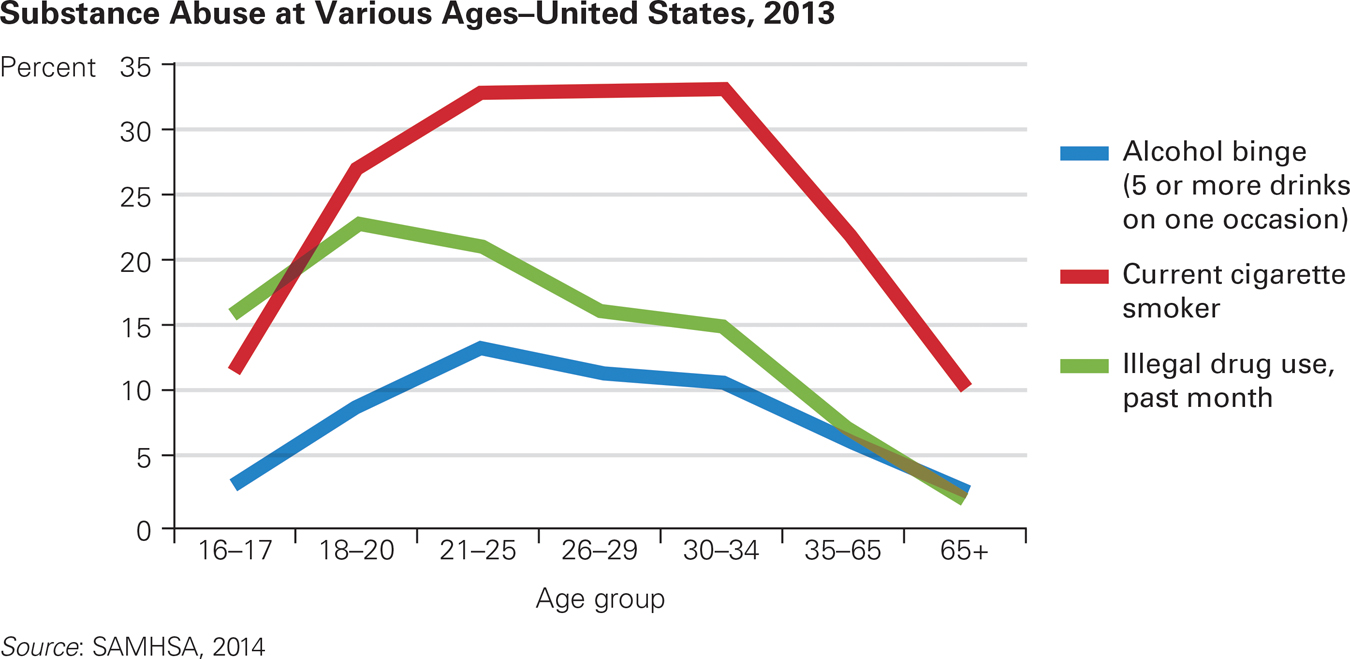

Drug abuse is more common among college students than among their peers who are not in college, partly because groups of emerging adults urge each other on. For instance, college students are most likely to engage in extreme drinking, with 25 percent of young college men reporting that they consumed 10 or more drinks in a row at least once in the previous two weeks (Johnston et al., 2009). Such extreme behavior arises from the same drive as extreme sports or other risks—

Too Old for That As you can see, emerging adults are the biggest substance abusers, but illegal drug use drops much faster than does cigarette use or binge drinking.

Especially for Substance Abuse Counselors Can you think of three possible explanations for the more precipitous drop in the use of illegal drug compared to legal ones?

Legal drugs could be more addictive, the thrill of illegality may diminish with age, or the fear of arrest may increase. In any case, treatment for young-

SUMMING UP Emerging adults are physiologically at their prime, with strong and healthy bodies. One strength is the sexual-

Video: College Binge Drinking shows college students engaging in (and rationalizing) this risky behavior.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 17.1

Why is maximum physical strength usually attained in emerging adulthood?

Every human body system is at optimal physical functioning during emerging adulthood. Many serious diseases have not yet developed, and some childhood ailments are outgrown. Physiologically, the early 20s are considered the prime of life.Question 17.2

What has changed, and what has not changed, in the past decades regarding sexual and reproductive development?

Biologically, the years from ages 18 to 25 are prime time for hard physical work and safe reproduction. However, the reality that young adults can carry rocks, plow fields, or haul water is no longer admired, nor is their fertility. If a contemporary young couple had a baby every year, their neighbors would be more appalled than approving. Now, societies, families, and young adults themselves expect more education, later marriage, and fewer children than was the norm a few decades ago.

Historically, most people married by age 20, had their first child within two years, and often a second and third before age 25.That has changed dramatically. The bodies of emerging adults still crave sex, but their minds know they are not ready for parenthood. For many, the solution is sex without pregnancy, made possible by modern contraception. The world's 2010 birth rate for 15–to 25– year– olds is half of what it was in 1960. Question 17.3

Why are STIs more common currently than 50 years ago?

There is a consequence of sexual freedom: the rise of STIs. The single best way to prevent STIs is lifelong monogamy, but most emerging adults practice serial monogamy, beginning a new relationship soon after one ends. At times a new sexual liaison overlaps an existing one, and sometimes a steady relationship is interspersed with a fling with someone else.Question 17.4

What are the social benefits of risk taking?

Many occupations are filled with risk–takers— police officers, military recruits, financial traders, etc. Facing fear is exhilarating and transformative, improving the individual's self– esteem without harming anyone. We would all suffer if young adults were always timid, traditional, and afraid of innovation. Question 17.5

Why are some sports more attractive at some ages than others?

Emerging adults may take part in risky sports such as motocross or snowboarding because they seek an adrenaline rush. The desire to experience a thrill may also overwhelm their ability to evaluate the potential risks associated with the activity, making emerging adults less concerned than older adults with the possibility of injury or death.Question 17.6

Why are serious accidents more common in emerging adulthood than later?

Many emerging adults bravely, or foolishly, risk their lives. The reasons for such risk–taking are social (showing off and vying for status) and biological (hormones, energy, and brain development). Question 17.7

Why are college students more likely to abuse drugs than those not in college?

Drug abuse—particularly of alcohol and marijuana— is more common among college students than among their peers who are not in college. Being with peers, especially for college men, seems to encourage many kinds of drug abuse.