Cognitive Development

You remember that each of Piaget’s four periods of child and adolescent development is characterized by major advances in cognition, with each advance representing a new stage. Adult thinking similarly differs from earlier thinking: It is more practical, more flexible, and better able to coordinate objective and subjective perspectives.

Postformal Thought and Brain Development

Especially for Someone Who Has to Make an Important Decision Which is better: to go with your gut feelings or to consider pros and cons as objectively as you can?

Both are necessary. Mature thinking requires a combination of emotions and logic. To make sure you use both, take your time (don’t act on your first impulse) and talk with people you trust. Ultimately, you will live with your decision, so do not ignore either intuitive or logical thought.

Many developmentalists believe that Piaget’s fourth stage, formal operational thought, is inadequate to describe adult thinking. Some propose a fifth stage, called postformal thought, a “type of logical, adaptive problem solving that is a step more complex than scientific formal-

As you remember from Chapter 15, adolescents use two modes of thought (dual processing) but they have difficulty combining them. They use formal analysis to learn science, distill principles, develop arguments, and resolve the world’s problems; alternatively, they think spontaneously and emotionally about personal issues. They prefer quick reactions, only later realizing the consequences.

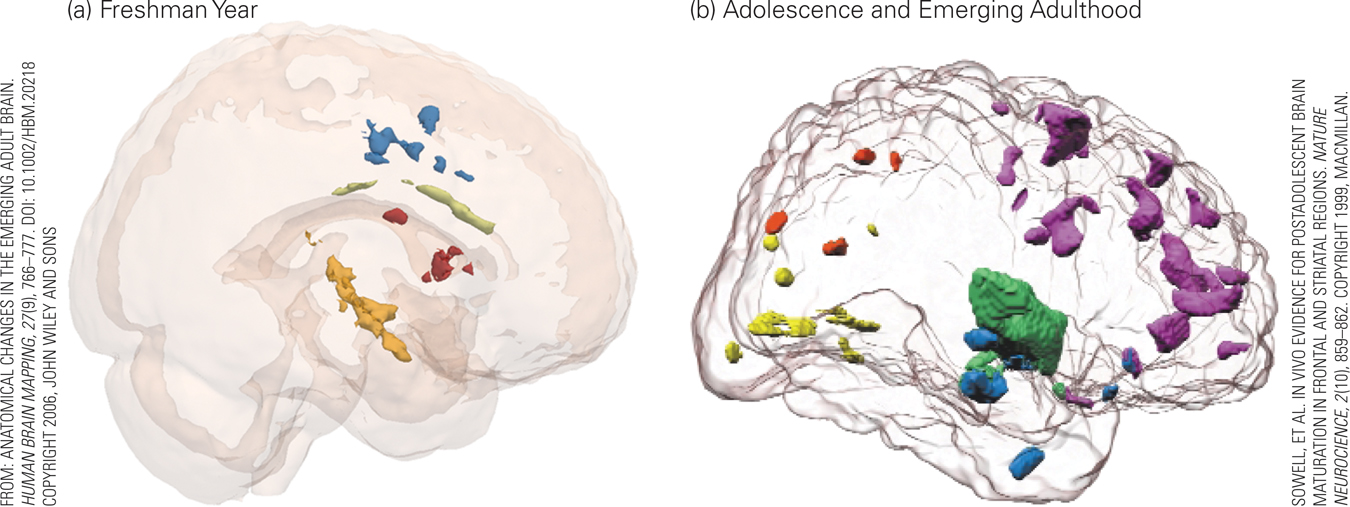

Neuroscience reveals that brains mature in many ways between adolescence and adulthood; scientists are not yet sure of the cognitive implications.

For a quick look at the changes that occur in a person’s brain between ages 18 and 25, try Video Activity: Brain Development: Emerging Adulthood.

Postformal thinkers are less impulsive and reactive. They take a more flexible and comprehensive approach, with forethought, noting difficulties and anticipating problems, not denying, avoiding, or procrastinating. As a result, postformal thinking is more practical, creative, and imaginative than thinking in previous cognitive stages (Wu & Chiou, 2008). It is particularly useful in human relationships (Sinnott, 2014).

As you have read, Piaget’s stage theory of childhood cognition is not accepted by all developmentalists. Many more question this fifth stage. As two scholars writing about emerging adulthood wrote, “Who needs stages anyway?” (Hendry & Kloep, 2011).

Piaget himself never labeled or described postformal cognition. Certainly, if cognitive stage means attaining a new set of intellectual abilities (such as the symbolic use of language that distinguishes sensorimotor from preoperational thought), then adulthood has no stages.

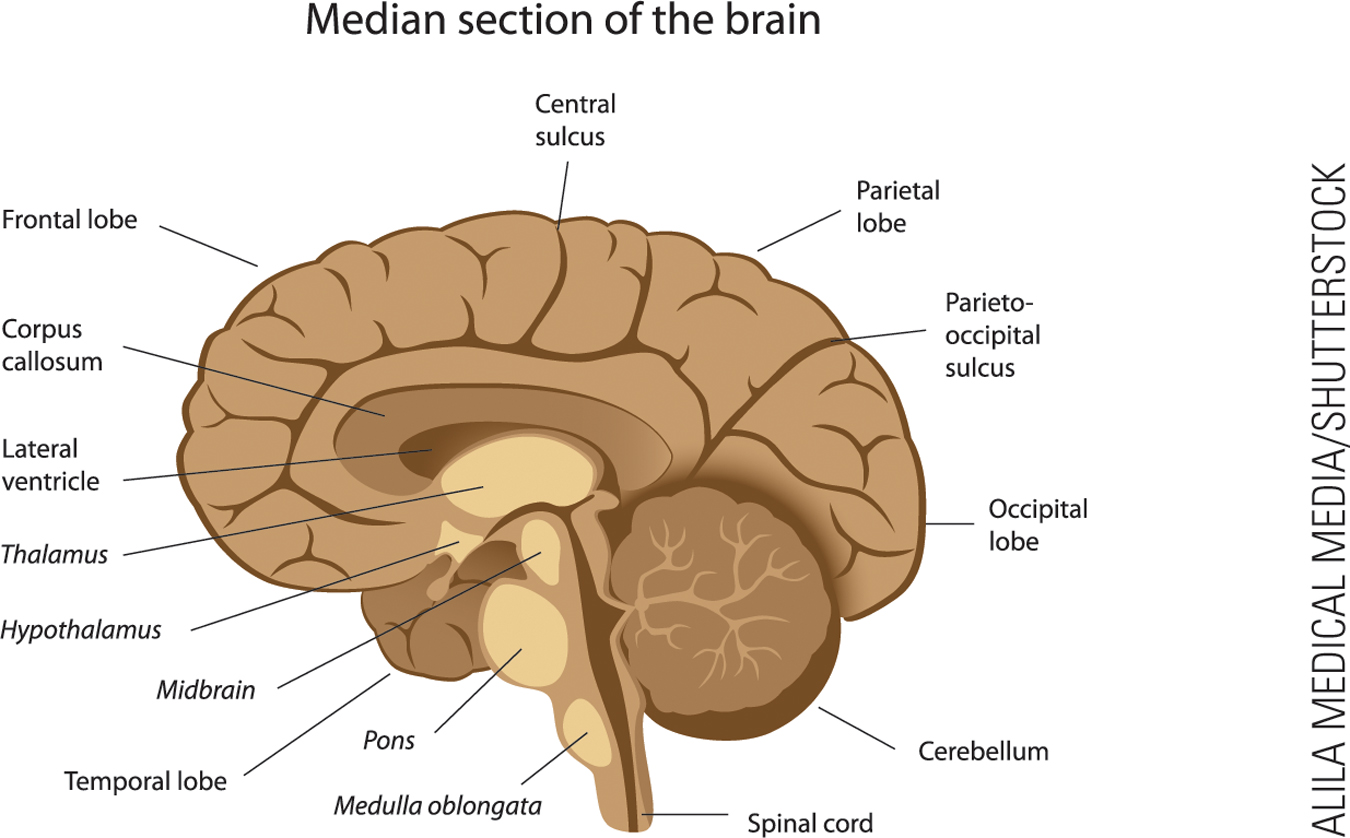

However, as described in Chapter 14, the prefrontal cortex is not fully mature until the early 20s, and new dendrites connect throughout life. As more is understood about brain development after adolescence, it seems that thinking may change as the brain matures (Lemieux 2012). Several studies find that adult cognition benefits from a wider understanding and greater experience of the social world (Sinnott, 2014).

Countering Stereotypes

Cognitive flexibility, particularly the ability to change childhood assumptions, helps counter stereotypes. Young adults show many signs of such flexibility. The very fact that emerging adults marry later than previous generations did suggests that, couple by couple, their thinking processes are not determined by their childhood culture or by traditional norms. Early experiences are influential, but postformal thinkers are not stuck in them.

Research on racial prejudice is another example. Many people are less prejudiced than their parents, and they believe they are not biased. However, tests may reveal implicit discrimination. Thus, many adults have both unconscious prejudice and rational tolerance—

Unfortunately, many people do not recognize their own stereotypes, even when false beliefs harm them. One of the most pernicious results is stereotype threat, arising in people who worry that other people might judge them as stupid, lazy, oversexed, or worse because of their ethnicity, sex, age, or appearance. Even the possibility of being stereotyped arouses emotions and hijacks memory, disrupting cognition (Schmader, 2010). That is stereotype threat.

a view from science

Stereotype Threat

One statistic has troubled social scientists for decades: African American men have lower grades in high school and earn only half as many college degrees as African American women. This cannot be genetic, since the women have the same genes (except one chromosome) as the men. Most scientists have blamed the context and historical discrimination that fell particularly hard on men (Arnett & Brody, 2008).

One African American scholar thought of another possibility, one that originated in the mind, not the social context. He labeled it stereotype threat, a “threat in the air,” not in reality (Steele, 1997). The mere possibility of being negatively stereotyped may arouse emotions that disrupt cognition as well as emotional regulation.

The hypothesis is that if African American males are aware of the stereotype that they are poor scholars, they become anxious in educational settings. That anxiety may increase stress hormones that reduce their ability to focus on intellectual challenges.

Then, if they score low, they might protect their pride by denigrating academics. That leads to disengagement from studying and still lower achievement. The more threatening the context, the worse they will do (Taylor & Walton, 2011).

Stereotype threat is more than a hypothesis. Hundreds of studies show that it harms almost all humans, not just African American men. Women underperform in math, older people are more forgetful, bilingual students stumble with English.

Every member of a stigmatized minority in every nation seems to handicap themselves because of what they imagine others might think (Inzlicht & Schmader, 2012). Not only academics but athletic prowess and health habits may be impaired if stereotype threat makes people anxious (Aronson et al., 2013).

The worst part of stereotype threat is that it is self-

The harm from anxiety is familiar to those who study sports psychology. When star athletes unexpectedly underperform because of stress (called “choking”), stereotype threat arising from past team losses may be the cause (Jordet et al., 2012). Many female players imagine they are not expected to play as well as men (e.g., someone told them “you throw like a girl”), and that itself impairs performance (Hively & El-

The researchers who first recognized stereotype threat wondered if it could be eliminated, or at least reduced. They hypothesized that if African American college men internalize (believe wholeheartedly, not just intellectually) that intelligence is plastic (incremental theory) rather than the inalterable product of genes and gender (entity theory), that belief might protect them from stereotype threat.

Using a clever combination of written material, mentoring, and videotaping, these scientists convinced African American students at Stanford University that their ability and hence their achievement depended on their personal efforts. That reduced stereotype threat and led to higher grades (Aronson et al., 2002).

This experiment intrigued the scientific community, but it involved only 79 exceptional students—

Soon thousands of scientists replicated and varied this study with many other populations. The results confirm that stereotype threat is pervasive but that it can be alleviated (Inzlicht & Schmader 2012; Sherman et al., 2013; Dennehy et al., 2014).

Does this finding from science apply to the general public? The answer depends on whether anxiety about what other people think ever affected your performance.

The Effects of College

Especially for Those Considering Studying Abroad Given the effects of college, would it be better for a student to study abroad in the first year or last year of a college education?

Since one result of college is that students become more open to other perspectives while developing their commitment to their own values, foreign study might be most beneficial after several years of college. If they study abroad too early, some students might be either too narrowly patriotic (they are not yet open) or too quick to reject everything about their national heritage (they have not yet developed their own commitments).

A major reason why emerging adulthood has become a new period of development, when people postpone the usual markers of adult life (marriage, a steady job), is that many older adolescents seek further education instead of taking on adult responsibilities. However, some aspects of higher education are controversial.

Massification

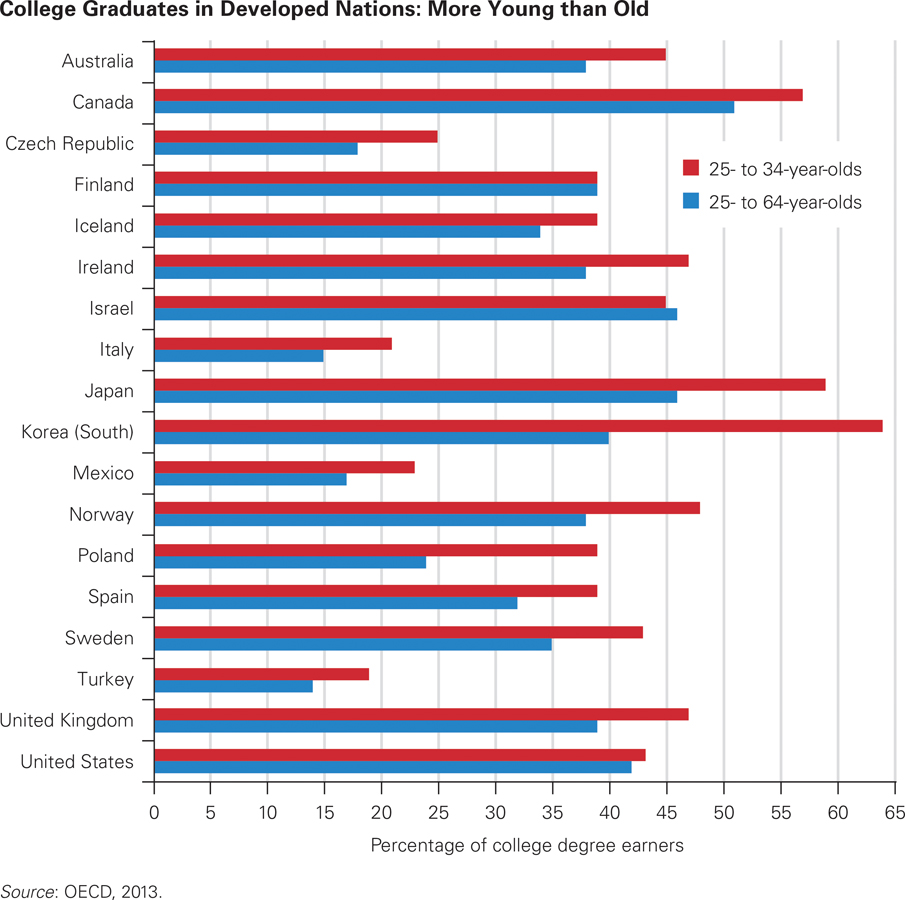

There is no dispute that tertiary education improves health and wealth. Because of that, every nation has increased the number of college students—

Video: The Effects of Mentoring on Intellectual Development: The University-

Send Your Children to College In many nations, the younger generations more often earn bachelor’s degrees (BA or BS) than their parents and grandparents. This table shows OECD nations and rates for 2011, the most recent year for which an international comparison is available. In many nations, the 2013 rates are somewhat higher, as the economic recession sent more young people to college, but the United States still lags behind.

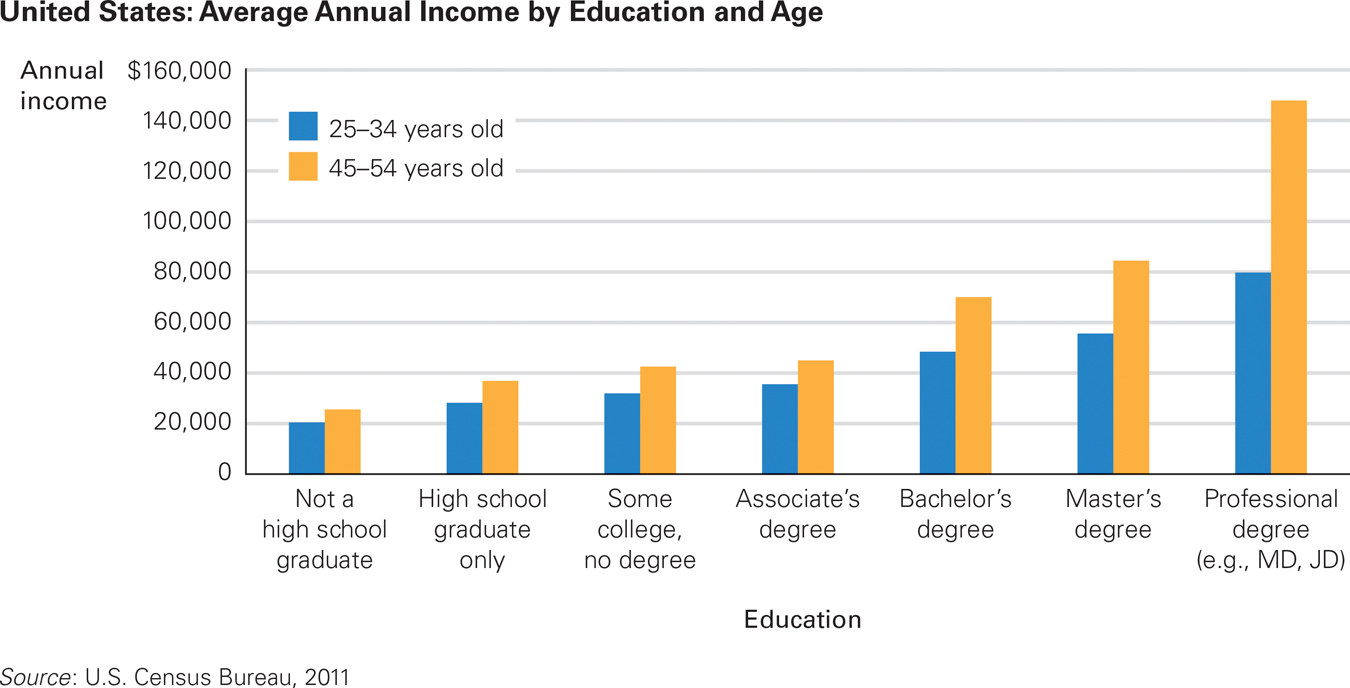

U.S. Census data and surveys of individuals find that college education pays off even more than it did thirty years ago, with the average college man earning $17,558 more per year than a high school graduate. Women also benefit from college, but not as much: Graduates earn $10,393 more per year (Autor, 2014).

The typical person with a master’s degree earns twice as much over a lifetime as the typical one with only a high school diploma (Doubleday, 2013) (see Figure EP.3). Parents almost universally want their children to go to college, and new college students expect to earn a degree. Only about half of them do so.

Older, Wiser, and Richer Adolescents find it easier to think about their immediate experiences (a boring math class) rather than their middle-

Perry found that the college experience itself causes this progression: Peers, professors, books, and class discussion all stimulate new questions and thoughts. Other research confirmed Perry’s conclusions. In general, the more years of higher education a person has, the deeper and more postformal that person’s reasoning becomes (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991).

College and Cognition

For developmentalists interested in cognition, the crucial question about college education is not about wealth, health, rates, or even graduation. Does college advance critical thinking and postformal thought?

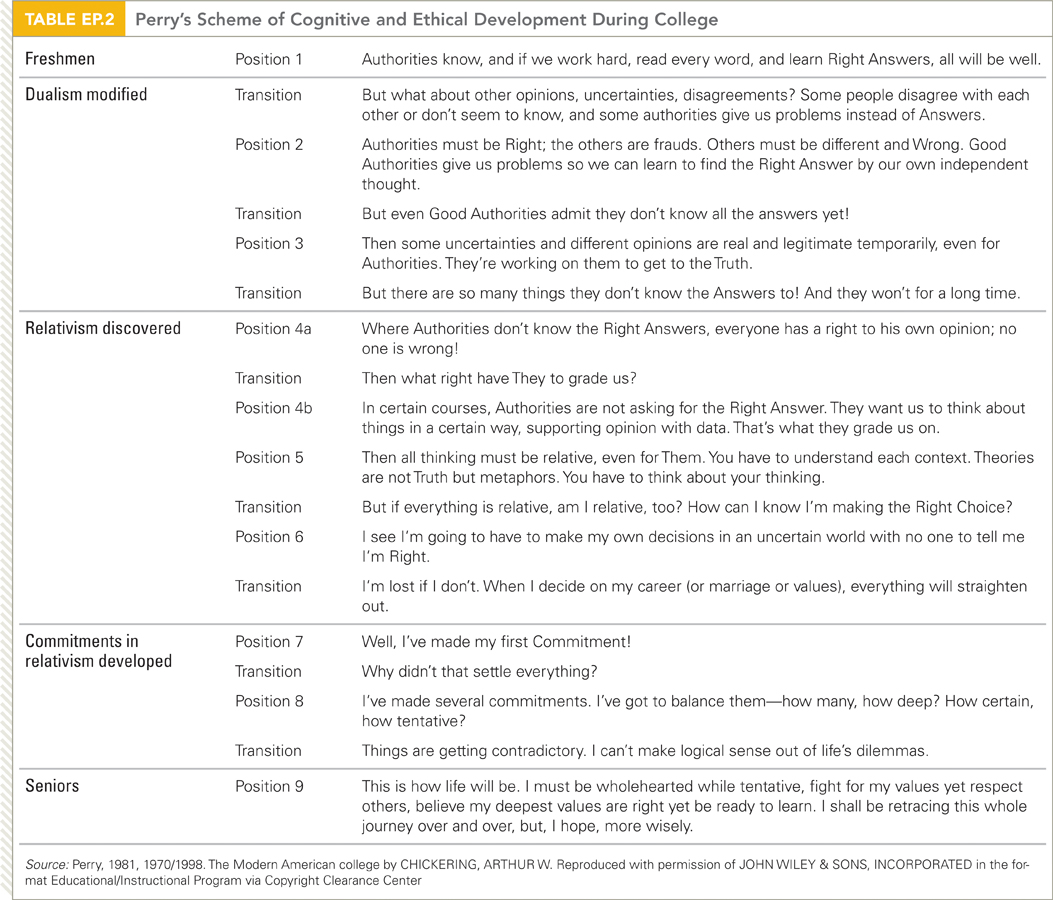

According to one classic study (Perry, 1981, 1970/1998), thinking progresses through nine levels of complexity over the four years that lead to a bachelor’s degree, moving from a simplistic dualism (right or wrong, yes or no, success or failure) to a relativism that recognizes a multiplicity of perspectives (see Table EP.2).

Current Contexts

But wait. You probably noticed that Perry’s study was first published in 1981. Hundreds of other studies also found that college education deepens cognition, but most of that research occurred in the twentieth century. Since you know that cohort and culture are crucial influences, you may wonder whether those conclusions still hold.

Many recent books criticize college education on exactly those grounds. Notably, a twenty-

The reasons were many: Students study less, professors expect less, and students avoid classes in which they must read at least 40 pages a week or write 20 pages a semester. Administrators and faculty still hope for intellectual growth, but rigorous classes are canceled or not required.

Especially for High School Teachers One of your brightest students doesn’t want to go to college. She would rather keep waitressing in a restaurant, where she makes good money in tips. What do you say?

Even more than ability, motivation is crucial for college success, so don’t insist that she attend college. Since your student has money and a steady job (prime goals for today’s college-

A follow-

Other observers blame the faculty, or the wider culture, for forcing colleges to follow a corporate model, with students as customers who need to be satisfied rather than intellectual youth who need to be challenged (Deresiewicz, 2014). Customers, apparently, demand dormitories and sports facilities that are costly, and students take out loans to pay for them. The fact that the United States has slipped in massification is not surprising, given the political, economic, and cultural contexts of contemporary college.

Two new pedagogical techniques may foster greater learning, or may be evidence of the decline of standards. One is called the flipped class, in which students are required to watch videos of a lecture on their computers before class, using class time for discussion, with the professor prodding and encouraging but not lecturing. The other technique is classes that are totally online, including massive open online courses (MOOCs). Thousands of students enroll in MOOCs and do all of the work hundreds or thousands of miles away.

MOOCs are most effective for students who are highly motivated and adept at computers. They learn best if they have another classmate, or an expert, as a personal guide: Face-

Motivation to Attend College

Motivation is crucial for every intellectual accomplishment. An underlying problem in the controversy about college education may be that people disagree about its purpose. Thus, students motivated to accomplish one thing clash with professors who are motivated to teach something else.

Developmentalists, most professors, and many college graduates believe that the main purpose of higher education is “personal and intellectual growth,” which means that professors should focus on fostering critical thinking and analysis. However, adults who have never attended college believe that “acquiring specific skills and knowledge” is more important.

In the Arum and Roksa report (2011), students majoring in business and other career fields were less likely to gain in critical thinking compared to those in the liberal arts (courses that demand more reading and writing). These researchers suggest that colleges, professors, and students themselves who seek easier, more popular courses are short-

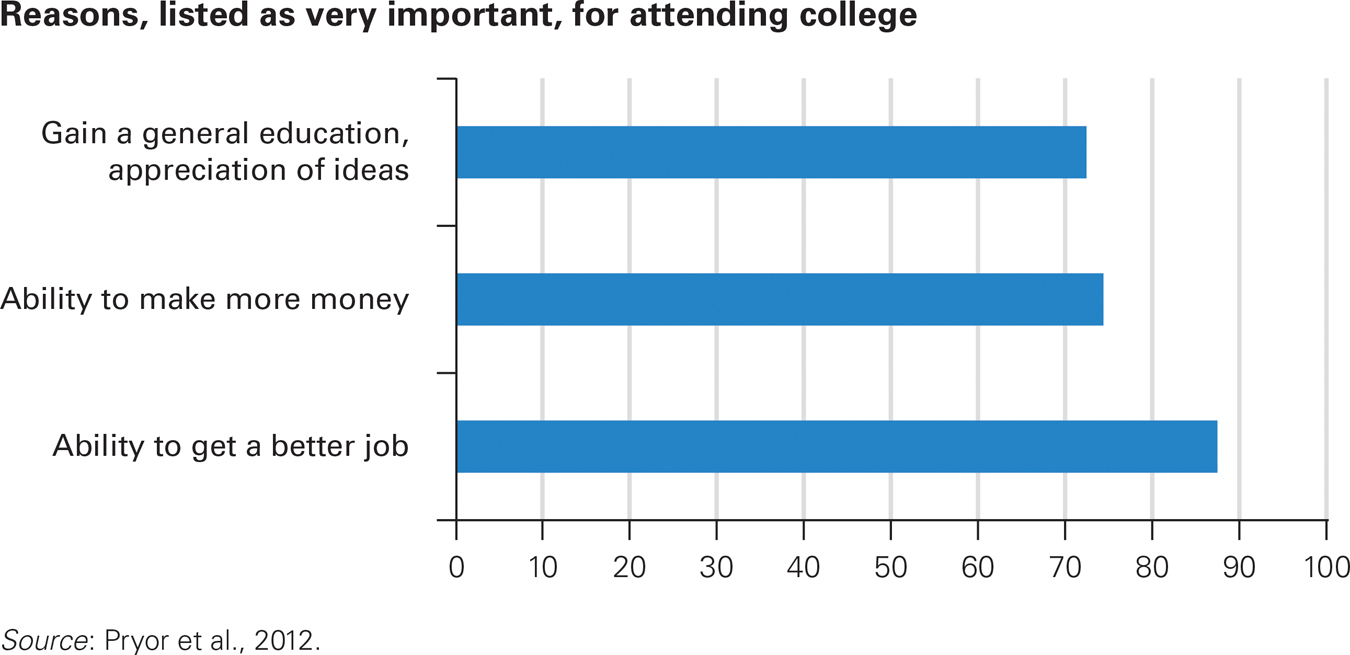

However, many students attend college primarily for career reasons (see Figure EP.4). They want jobs with good pay; they select majors and institutions accordingly, not for intellectual challenge and advanced communication skills. Professors are often critical when college success is measured via the salaries of graduates, but that metric may be what the public expects college to provide.

In 1955, most U.S. colleges were four-

Cohort Shift Students in 1980 thought new ideas and a philosophy of life were prime reasons to go to college—

Similarly, for-

No nation has reached consensus on the purpose of college. For example in China, where the number of college students now exceeds the United States (but remember that the Chinese population is much larger), the central government has fostered thousands of new institutions of higher learning, primarily to advance the economy, not to deepen intellectual understanding. However, even in that centralized government, disagreement about the goals and practices of college is evident (Ross & Wang, 2013).

In 2009, a new Chinese university (called South University of Science and Technology of China, SUSTC) was founded to encourage analysis and critical thinking. SUSTC does not require prospective students to take the national college entry exam (Gao Kao); instead, “creativity and a passion for learning” are the admission criteria (Stone, 2011, p. 161). It is not clear whether SUSTC is successful, in part because people disagree about how to measure success. The Chinese government praises SUSTC’s accomplishments but has not replicated it (Shenzhen Daily, 2014).

The Effects of Diversity

At least one characteristic of the twenty-

In addition, students’ ethnic, economic, religious, and cultural backgrounds are more varied. Compared to 1970, more students are parents, are older than age 24, are of non-

OBSERVATION QUIZ Which is a community college?

The one with the flags is Kingsborough Community College, in Brooklyn, New York; the one with a colonnade is UCLA (University of California in Los Angeles). If you guessed right, what clues did you use?

Discussion among people of different backgrounds and perspectives leads to intellectual challenge and deeper thought. The benefits of a diverse student body last for years after graduation (Pascarella et al., 2014). Colleges that make use of their new diversity—

When 18-

SUMMING UP Emerging adults often become more flexible, creative, and coordinated thinkers than they were as adolescents, an advancement sometimes described as postformal thought. College education brings health and wealth to graduates, and nations worldwide have increased the number of students in college. Research in earlier decades in the United States finds that college also advances cognition, helping students become more critical thinkers as well as more flexible. However, some find that those cognitive effects are less evident than they were previously, especially since many current students seek skills and knowledge for career purposes, not for intellectual challenge. Nonetheless, college typically broadens a person’s perspective, as the diversity of students and the opportunity to understand and debate new ideas lead to deeper, more flexible, thought.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 17.8

Why did scholars choose the term postformal to describe the fifth stage of cognition?

Many developmentalists believe that Piaget's fourth stage, formal operational thought, is inadequate to describe adult thinking. Some propose a fifth stage called postformal thought, a type of logical, adaptive problem solving that is a step more complex than scientific formal–level Piagetian tasks. As one group of scholars explained, in postformal thought one can conceive of multiple logics, choices, or perceptions . . . in order to better understand the complexities and inherent biases in truth. Question 17.9

How does postformal thinking differ from typical adolescent thought?

Postformal thinkers are less impulsive and reactive. They take a more flexible and comprehensive approach with forethought, noting difficulties and anticipating problems, not denying, avoiding, or procrastinating. As a result, postformal thinking is more practical, creative, and imaginative than thinking in previous cognitive stages. It is particularly useful in human relationships.Question 17.10

Why might the threat of a stereotype affect cognition?

Stereotype threat arises in people who worry that other people might judge them as stupid, lazy, oversexed, or worse because of their ethnicity, sex, age, or appearance. Even the possibility of being stereotyped arouses emotions and hijacks memory, disrupting cognition.Question 17.11

Who is vulnerable to stereotype threat and why?

Individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds may be especially vulnerable to stereotype threat, as are sexual minorities. Older adults and adults with certain physical attributes, such as being overweight, are also at–risk for stereotyping. Question 17.12

How do current college enrollment patterns differ from those of 50 years ago?

Compared to 50 years ago, many young adults are postponing the usual markers of adult life (marriage, a steady job) and instead are seeking higher education. Every nation has increased the number of college students—a phenomenon called massification. Question 17.13

Why do people disagree about the goals of a college education?

Developmentalists, most professors, and many college graduates believe that the main purpose of higher education is “personal and intellectual growth,” which means that professors should focus on fostering critical thinking and analysis. However, adults who have never attended college believe that “acquiring specific skills and knowledge” is more important. In addition, many students attend college primarily for career reasons. They want jobs with good pay; they select majors and institutions accordingly, not for intellectual challenge and advanced communication skills. Professors are often critical when college success is measured via the salaries of graduates, but that metric may be what the public expects college to provide. No nation has reached consensus on the purpose of college.