10.5 Drug Use and Abuse

Adolescents enjoy doing something forbidden. Moreover, their hormonal surges and brain patterns increase the reward sensations produced by drugs. But their developing bodies and brains make drug use particularly hazardous.

Variations in Drug Use

Most teenagers try psychoactive drugs, which are drugs that affect the mind. Although police officers are concerned primarily with the legal issues of drug use, developmentalists are more concerned that cigarettes, alcohol, and many prescription medicines are as addictive and damaging as illegal drugs like marijuana, cocaine, and heroin.

Canadian studies have shown that the three most popular drugs among youth are tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis (Vega et al., 2002). In 2012, Statistics Canada reported that, among youths aged 15 to 24, use of cannabis was three times higher than among adults 25 and older, and use of drugs such as cocaine, speed, hallucinogens, ecstasy, and heroin was five times higher (Health Canada, 2011). Generally, both the prevalence and incidence of drug use increase every year from age 10 to 25, and then decrease. Use before age 18 predicts later abuse.

The exception to this developmental pattern is inhalants (fumes from aerosol containers, cleaning fluid, etc.), which are used more by younger adolescents, partly because they can be easily purchased. Sadly, the youngest adolescents are least able, cognitively, to analyze risks, and parents rarely suspect a drug problem.

Variations By RegionNations vary markedly in drug use. Consider the most common drugs: alcohol and tobacco. In most European nations, alcohol is widely used, even by children. In contrast, in much of the Middle East, alcohol use is illegal and teenagers almost never drink. In many Asian nations, anyone may smoke anywhere; in the United States, smoking is forbidden in many schools and public places, but advertised widely; in Canada, cigarette smoking is forbidden in schools and public places, and cigarette advertising is outlawed. Canadian and U.S. teens of both sexes smoke fewer cigarettes than Western European teens, and Canadian teens smoke less than U.S. teens. Even within Canada, cigarette smoking varies by region. For example, in 2010–

385

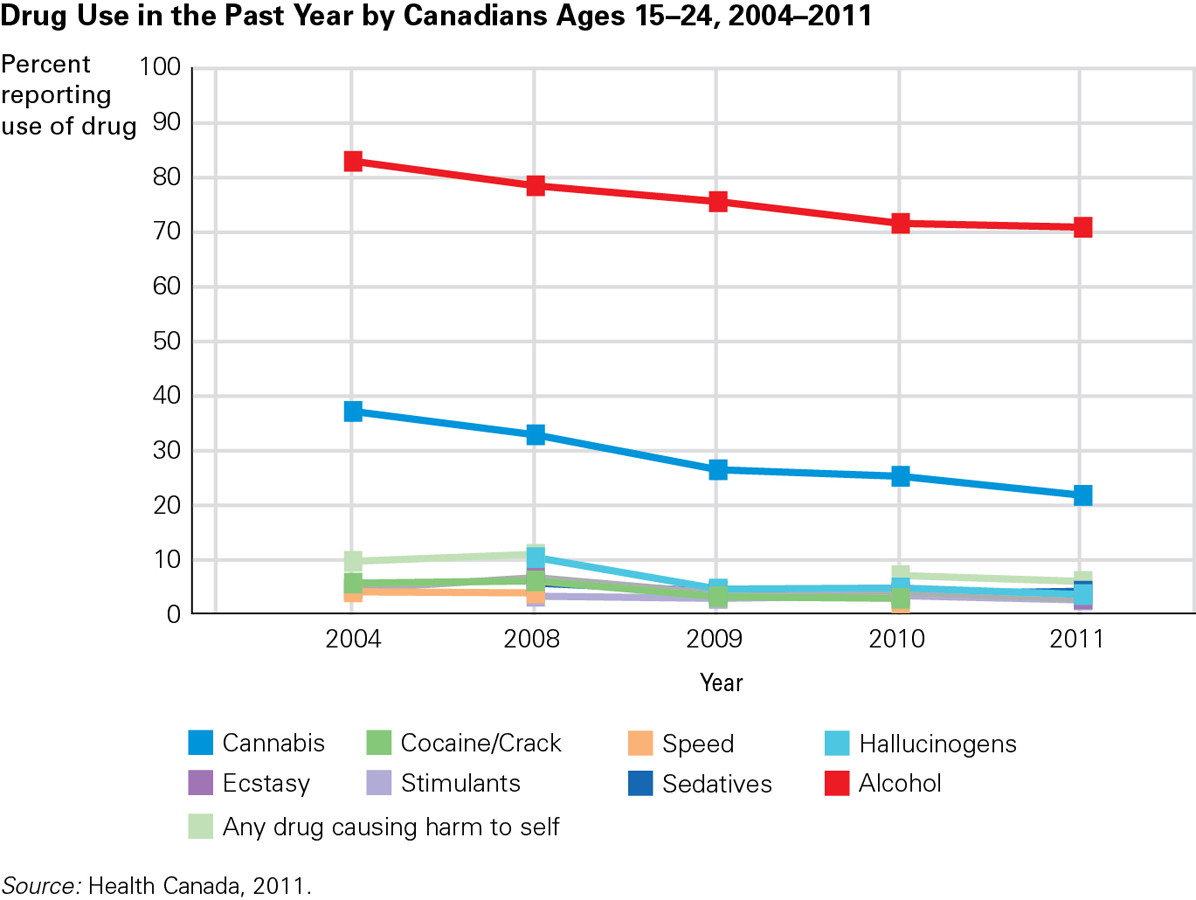

Variations By Generation And GenderThe specifics of use and abuse vary historically and culturally, partly because each generation develops a distinct pattern to differentiate itself from the earlier cohorts and other cultures. Use of drugs has decreased or stayed the same in Canada since 2004 (as Figure 10.5 shows).

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Which of the drugs listed here do you think are relatively more accessible to youth, and subject to more lenient possessions laws?

Cannabis and alcohol are more accessible to youth, which accounts for their higher percentage of reported use among youth than other drugs.

386

With some exceptions, adolescent boys use more drugs, and use them more often, than girls do, especially outside North America. An international survey of 13-

These gender differences are reinforced by social constructions about proper male and female behaviour. In Indonesia, for instance, 38 percent of the boys smoke cigarettes, but only 5 percent of the girls do. One Indonesian boy explained, “If I don’t smoke, I’m not a real man” (quoted in Ng et al., 2007).

A recent report from the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse found few gender differences in alcohol or cannabis use among Canadian students aged 12 to 18; however, more males report drinking and consuming cannabis before driving (Young et al., 2011). In addition, young men are more likely to report risky drinking (defined as four or more drinks for women, and five or more drinks for men on one occasion) than are women: 62.9 percent compared to 50.1 percent (Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 2013).

Harm from Drugs

Many teenagers believe that adults exaggerate the evils of drug use and think it hypocritical that a parent who has cocktails before dinner or beer with lunch would dare prohibit adolescent drug use. Nonetheless, developmentalists see both immediate and long-

Addiction and brain damage are among the consequences of drug use that appear to be more pronounced in adolescents than in adults, a difference that has been linked to brain maturation (Moffitt et al., 2006). Few adolescents notice when they move past use (experimenting) to abuse (experiencing harm) and then to addiction (needing the drug to avoid feeling nervous, anxious, or in pain). They do not know or care that every psychoactive drug excites the limbic system and interferes with the prefrontal cortex. Drug users are thus more emotional (specifics vary, from ecstasy to terror, paranoia to rage) than they otherwise would be, as well as less reflective. Every hazard of adolescence—

In terms of specific drugs, a negative effect of tobacco that impacts teens in particular is that it impairs digestion and nutrition, slowing down growth. Abuse of tobacco occurs with bidis, cigars, pipes, and chewing tobacco, as well as with cigarettes. In India, widespread tobacco use is one reason for chronic undernutrition (Warren et al., 2006). Since internal organs continue to mature after the height spurt, cigarette-

ESPECIALLY FOR Parents Who Drink Socially You have heard that parents should allow their children to drink at home, to teach them to drink responsibly and not get drunk elsewhere. Is that wise?

No. Alcohol is particularly harmful for young brains. Children who are encouraged to drink with their parents are more likely to drink when no adults are present. Instead, ensure that children understand the risks associated with drinking.

Alcohol is the most frequently abused drug in North America. Heavy drinking impairs memory and self-

Like many other drugs, alcohol allows momentary denial of problems: Worries seem to disappear when a person is under the influence. When ignored, problems get worse and more alcohol is needed—

387

Similarly, marijuana seems harmless to many teenagers, partly because users seem more relaxed than inebriated. A girl named Johanna said:

I started off using about every other weekend, and pretty soon it increased to three to four times a week…. I started skipping classes to get high. I quit soccer because my coach was a jerk. My grades dropped, but I blamed that on my not being into school…. Finally, some of my friends cornered me and told me how much I had changed, and they said it started when I started smoking marijuana. They came with me to see the substance-

[Bell, 1998]

Johanna’s future was in jeopardy. Adolescents who regularly smoke marijuana are more likely to drop out of school, become teenage parents, and be unemployed. Marijuana affects memory, language proficiency, and motivation (Lane et al., 2005)—all of which are especially crucial during adolescence. An Australian study found that even occasional marijuana use (once a week) before age 20 affected development up to 10 years later (Degenhardt et al., 2010).

These are correlations, which, as you know, do not reveal causation. Is it possible that adolescents who are not particularly clever or ambitious choose to smoke marijuana, rather than vice versa? Is some third variable (such as hostile parents) the cause of both academic problems and drug use, rendering the correlation deceptive? This seems plausible because drug-

These questions led to the hypothesis that the psychic strains of adolescence lead to drug use, not vice versa. In fact, however, longitudinal research suggests that drug use causes more problems than it solves, often preceding anxiety disorders, depression, and rebellion (Chassin et al., 2009; Meririnne et al., 2010).

Marijuana use is particularly common among wealthier adolescents, who then become less motivated to achieve in school and more likely to develop other problems (Ansary & Luthar, 2009). Rather than lack of ambition leading to marijuana use, marijuana itself destroys ambition.

388

Preventing Drug Abuse: What Works?

Drug abuse is a progression, beginning with a social occasion and ending alone. The first use usually occurs with friends, which leads adolescents to believe that occasional use is an expression of friendship or generational solidarity. Few adolescent drug users are addicts, and, for those who are, usually they and their friends are unaware of it. However, the younger a person is when beginning occasional drug use, the more likely addiction will eventually occur. That may not persuade young adolescents, who, as you remember, think they are invulnerable exceptions to any rule.

With harmful drugs, as with many other aspects of life, each generation prefers to learn things for themselves. A common phenomenon is generational forgetting, the idea that each new generation forgets what the previous generation learned (Chassin et al., 2009; Johnston et al., 2010). Mistrust of the older generation, added to loyalty to one’s peers, leads not only to generational forgetting, but also to a backlash. If adults say something is forbidden, that is a reason to try it.

Some antidrug curricula and advertisements using scare tactics (such as the one that showed eggs being broken into a hot frying pan while an announcer intoned, “This is your brain on drugs”) have the opposite effect than intended, increasing rather than decreasing drug use. One reason may be that such advertisements make drugs seem exciting; another may be that adolescents recognize the exaggeration. Similarly, anti-

Changing the social context has an impact. For example, Aboriginal people in North America are significantly more likely to smoke than the general population. This is due to availability of inexpensive cigarettes (tax-

All the research confirms that parents are influential, yet many parents are unaware of their children’s drug use, so their educational efforts may be too late, too general, or too naive. When parents forbid smoking in their homes, fewer adolescents smoke (Messer et al., 2008); when parents are careful with their own drinking, fewer teenagers abuse alcohol (Van Zundert et al., 2006). When parents provide guidance about drinking, teenagers are less likely to get drunk or use other substances (Miller & Plant, 2010). In addition, growing up with two married parents reduces cigarette and alcohol use, even when other influences (such as parental smoking and family income) are taken into account (Brown & Rinelli, 2010). The probable reasons include better parent–

It is apparent that, although puberty is a universal biological process, its effects vary widely. Sharply declining rates of teenage pregnancy, abortions, suicides, homicides, and use of several legal and illegal drugs are evident in many nations. Changing times bring new iterations of the identity crisis. Human growth starts with genes when a single sperm penetrates a single ovum, but it certainly is not wholly determined by biology. This will be even more apparent in the next five chapters: By the end of adolescence a person has completed body growth but not development. No adult of any age is unchanged over the past five years, and no one will be the same five years hence.

389

KEY Points

- Many adolescents try psychoactive drugs; however, alcohol and marijuana use are most common among Canadian youth.

- Countries vary tremendously in the legality and availability of drugs.

- Adolescents are often unaware of the dangers of drugs, which are particularly harmful to the developing brain and body.

- Drug use is highest among Canadian youth as compared to other age groups.

- Some educational measures to halt adolescent drug use are not effective, but parental example and changing the social context have reduced prevalence.