12.3 What is Adult Intelligence?

SALVATORE DI NOLFI/EPA/CORBIS

You just read that both education and intelligence, measured by IQ tests, might explain why high-

One leading theoretician, Charles Spearman (1927), proposed a single entity that he called general intelligence (g). Although g cannot be measured directly, it can be inferred from various abilities, such as vocabulary, memory, and reasoning. Most experts who agree with Spearman contend that children gain in ability as they mature, and thus scores on intelligence tests take a child’s age into account. Once a person reaches adulthood, an IQ score indicates whether that adult is a genius, average, or below average, no matter what the person’s age. The same IQ test is taken at age 18 or 88.

The belief that g exists still influences thinking and testing on intelligence. Many neuroscientists seek genetic underpinnings for the intellectual differences among adults. However, efforts to find specific genes or abilities that comprise g have not succeeded (Deary et al., 2010; Haier et al., 2009). Some researchers believe g does not exist.

444

Research on Age and Intelligence

Research on intelligence over the years of adulthood has reached conflicting conclusions (Hertzog, 2011). Cross-

The Flynn EffectThe most plausible hypothesis for the divergence between the conclusions of cross-

In many nations, the typical 75-

The same factors explain the results of longitudinal research. Contemporary 75-

As a result it is unfair—

Cross-

ESPECIALLY FOR Older Brothers and Sisters If your younger siblings mock your ignorance of current TV shows and beat you at the latest video games, does that mean your intellect is fading?

No. While it is true that each new cohort might be smarter than the previous one in some ways, cross-sequential research suggests that you are smarter than you used to be.

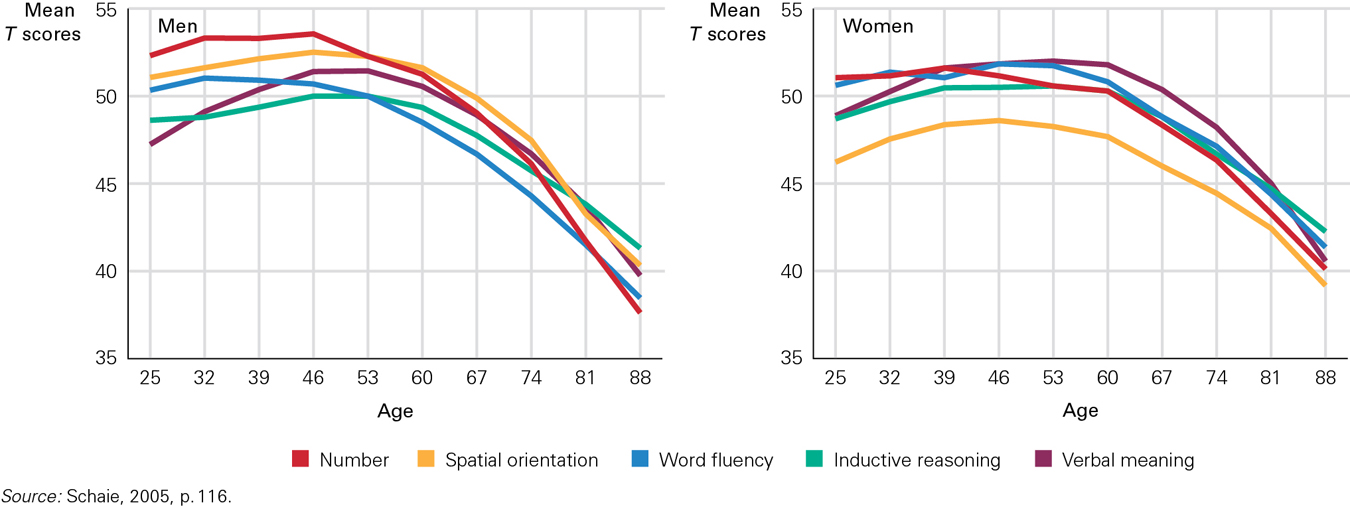

As an undergraduate in the middle of the twentieth century, K. Warner Schaie began to study adult intelligence. For his doctoral dissertation, he tested 500 adults, aged 20 to 50, on five standard primary mental abilities thought to be the foundation of intelligence: (1) verbal meaning (vocabulary), (2) spatial orientation, (3) inductive reasoning, (4) number ability, and (5) word fluency (rapid verbal associations). Schaie’s initial cross-

He then had a brilliant idea: He would not only retest his initial participants, he would also test a new young group who were the same age as his earlier sample had been. By comparing the scores of the retested individuals with their own earlier scores and with the scores of a new group who were the same age as his first group had been, he hoped to learn more about age and intelligence. His results surprised the experts; he discovered cohort effects that few people had imagined earlier.

For example, each successive cohort scored higher in verbal memory and inductive reasoning, but scored lower in number ability than adults who had been tested seven years earlier at the same age. That led to the hypothesis that classroom teaching affected ability: The curriculum in many U.S. schools had shifted by mid-

445

Schaie found that one correlate of higher ability was intellectual complexity at work and at home, both of which tended to peak in middle age, from ages 39 to 53. Because of complexity, women of earlier cohorts, who often stayed home or had less challenging jobs, lost IQ in mid-

Schaie conducted the first massive cross-

Many other researchers have reported similar results (Alwin, 2009). For example, Paul Baltes (2003) tested hundreds of older Germans in Berlin and found that only at age 80 did every cognitive ability show age-

Components of Intelligence: Many and Varied

Developmentalists are now looking closely at patterns of cognitive gains and losses over the adult years. These patterns vary markedly; intelligence often rises and falls within the same person, as “vast domains of cognitive performance…may not follow a common, age-

As you read in Chapter 7, many psychologists envision multiple intellectual abilities (Roberts & Lipnevich, 2012). One influential proposal—

446

Fluid and Crystallized IntelligenceIn the 1960s, leading personality researcher Raymond Cattell teamed up with a graduate student, John Horn, to study intelligence tests. They concluded that adult intelligence is best understood if various measures are grouped into two categories: fluid and crystallized (Horn & Cattell, 1967).

PRIYANKA SEKHAR

As its name implies, fluid intelligence is like water, flowing to its own level no matter where it happens to be. Fluid intelligence is quick and flexible, enabling people to learn anything, even things that are unfamiliar and unconnected to what they already know. Curiosity, learning for the joy of it, and the thrill of discovering something new are marks of fluid intelligence (Silvia & Sanders, 2010).

People high in fluid abilities can draw inferences, understand relations between concepts, and quickly process new ideas and facts. They are fast and creative with words and numbers and enjoy intellectual puzzles. The kind of question that tests fluid intelligence among Western adults might be like these:

What comes next in each of these two series?

4 9 1 6 2 5 3

V X Z B D⋆

Puzzles are often used to measure fluid intelligence, with speedy solutions earning bonus points (as on many IQ tests). Efficient working memory—

A study of adults aged 34 to 83 found that stresses and stressors did not vary by age, but did vary by fluid intelligence. People high in fluid intelligence were more often exposed to stress but were less likely to suffer from it: They used their intellect to turn potential stressors into positive experiences (Stawski et al., 2010). Fluid intelligence is associated with openness to new experiences and overall brain health (Batterham et al., 2009; Silvia & Sanders, 2010), which may contribute to an ability to detoxify stress. That may be one reason why high fluid intelligence in emerging adulthood leads to longer life and higher IQ later in adulthood.

By contrast, the accumulation of facts, information, and knowledge as a result of education and experience is called crystallized intelligence. Size of vocabulary, knowledge of chemical formulas, and memory for dates all indicate crystallized intelligence. Tests to measure this intelligence might include questions like these:

What is the meaning of the word misanthrope?

Who would hold a harpoon?

What was Sri Lanka called in 1950?§

447

Although questions that test for crystallized intelligence seem to measure education more than aptitude, these two are connected, especially in adulthood. Intelligent adults read widely, think deeply, and remember what they learn: Crystallized intelligence reflects fluid intelligence. Consequently, many researchers consider years of education a rough indication of IQ.

Age complicates the calculation of adult IQ. Scores on items measuring fluid intelligence decrease with age since everything in the brain as well as the body slows down. However, if a person continues to read and think, scores on items measuring crystallized intelligence increase. These two clusters, changing in opposite directions, make a person’s IQ score (composed of diverse subtests) fairly steady from ages 30 to 70, even though particular abilities change.

Barring pathology, the brain slowdown is rarely apparent until massive declines in fluid intelligence begin to affect crystallized intelligence, perhaps at age 70 or so. It may be foolish to try to measure g, a single omnibus intelligence, because both fluid and crystallized intelligence need to be measured separately.

When thinking about age changes in fluid and crystallized intelligence, note the connection between speed and IQ. Many items that test fluid intelligence are timed, with extra points for quick answers. In a culture that values youth, abilities that favour the young (e.g., fast reaction time, capacious short-

Thus, fluid intelligence is valued in a youth-

Three Forms of Intelligence: Sternberg Robert Sternberg (1988, 2003) agrees that the notion of a single intelligence score is misleading. As first mentioned in Chapter 7, Sternberg proposed three fundamental forms of intelligence: analytic, creative, and practical. Each can be tested.

Analytic intelligence includes all the mental processes that foster academic proficiency. It draws on abstract planning, strategy selection, focused attention, memory, and information processing, as well as on verbal and logical skills. Strengths in those areas are particularly valuable for younger adults in higher education and job training. Multiple-

ESPECIALLY FOR Prospective Parents What types of intelligence are most needed for effective parenting?

Because parenthood demands flexibility and patience, Sternberg’s practical intelligence or Gardner’s social understanding is probably most needed. Anything that involves finding a single correct answer, such as analytic intelligence or number ability, would not be much help.

Creative intelligence involves the capacity to be intellectually flexible and innovative. Creative thinking is divergent rather than convergent, valuing unexpected, imaginative, and unusual thoughts rather than standard and conventional ones. Sternberg developed tests of creative intelligence that include writing a short story titled “The Octopus’s Sneakers” or planning an advertising campaign for a new doorknob. High scores are earned by those with many unusual ideas.

Practical intelligence involves the capacity to adapt to the demands of a given situation. This includes an accurate grasp of the expectations and needs of the people involved and an awareness of the particular skills that are called for, along with the ability to use these insights effectively. If employers want to assess practical intelligence, they might test workers with a case study or see how they function on the job. Practical intelligence is sometimes called tacit intelligence because it is not obvious on tests. Instead it comes from “the school of hard knocks” and is sometimes called “street smarts” rather than “book smarts.”

Practical intelligence is needed in adulthood. It allows a person to manage the conflicting personalities in a family or to convince members of an organization (e.g., a business, a social group, or a school) to do something. Ideally, practical intelligence gradually builds over the years, as people learn from experience. Flexibility is also needed, as you will soon see in the discussion of expertise (K. Sloan, 2009).

448

Without practical intelligence, a solution found by analytic intelligence is doomed to fail because people resist academic brilliance as unrealistic and elite. Similarly, a stunningly creative idea may be rejected as ridiculous without practical intelligence.

Sternberg believes that each of these three forms of intelligence is useful; adults ideally deploy the strengths and guard against the limitations of each. Choosing which type of intelligence to use takes wisdom, which Sternberg has added as a fourth ingredient of successful intelligence. He writes:

One needs creativity to generate novel ideas, analytical intelligence to ascertain whether they are good ideas, practical intelligence to implement the ideas and persuade others of their value, and wisdom to ensure that the ideas help reach a common goal.

[Sternberg, 2012]

Think about these intelligences cross-

The fact that those who do well in college or university might not adapt well to life outside of school raises the question—

BLUE JEAN IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES

449

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

What Makes a Good Parent?

Tests of good infant care have been developed, based primarily on analytic, not practical, child-

Such knowledge seems helpful. For example, mothers and fathers who score higher on the KIDI are less depressed and more likely to provide responsive baby care (Howard, 2010; Zolotor et al., 2008). Many researchers believe that knowledge of infant development causes (not merely correlates with) good care.

Should we worry when mothers do not know about their babies’ growth? Perhaps. For instance, in one study only 29 percent of immigrant mothers knew that 2-

The opposing perspective suggests that knowledge of infant development does not matter in caregiving. A study supporting this view found that an immigrant child’s later cognitive development was best predicted not by KIDI scores or other measures of parenting, but by parents’ SES and language use. In this longitudinal study, the mothers’ KIDI scores did not predict later school success for Asian-

In another study, researchers provided supportive, encouraging visitors to low-

A significant impact of this intervention was its effect on the mothers’ ability to create home environments more suitable for the needs of their infants…despite lack of measurable change in mothers’ knowledge of infant development.

[Katz et al, 2011, p. S81]

In other words, advances in practical skills, not analytic ones, made a difference.

Knowledge may not be the only way to improve parenting. Instead, warmth and patience, responsiveness (without expecting an infant to reciprocate), mental health, or social support networks may be more critical than knowledge.

Part of the underlying reason why tests of knowledge do not always predict good parenting is that cultures vary in what they believe about infant development. For example, an anthropologist studied the Ache in Paraguay. They were respectful and deferential to her on repeated visits, until she and her husband

arrived at their study site in the forest of Paraguay with their infant daughter in tow. The Ache greeted her in a whole new way. They took her aside and in friendly and intimate but no-

[Small, 1998]

How important to quality care is accurate knowledge of child development? The way knowledge is interpreted and used by parents is complicated by various factors such as culture and SES, as we have just read. In the end, the most important aspect of good parenting may not be information, and the sign of an intelligent adult may be something other than analytic intelligence. What we do know about child care is that parents need to be continually responsive and sensitive to their children’s development, both of which require creative and practical intelligence.

450

KEY Points

- Cross-

sectional research shows declines in the IQ scores of adults, longitudinal research shows increases, and cross- sequential research shows cohort effects. - Worldwide improvements in health and education have advanced adult intelligence.

- Fluid intelligence declines with age; crystallized intelligence advances.

- Analytic, creative, and practical intelligence are each more important in certain contexts and cultures than in others.

*fluid intelligence answers are 6 and F; other answers are possible.

§The crystallized intelligence answers might be: someone who dislikes people; a fisherman who caught whales or swordfish in the past; Ceylon.