12.4 Selective Gains and Losses

Aging neurons, cultural pressures, historical conditions, and past schooling all affect adult cognition, as just reviewed. None of these is under direct individual control. However, adults can choose what abilities to nurture. For example, many adults use calculators instead of paper-

Optimization with Compensation

Paul and Margret Baltes (1990) developed a theory, called selective optimization with compensation, to describe the general process of systematic function (P. B. Baltes, 2003) as older adults maintain a balance in their lives. The idea is that people seek to optimize their development, looking for the best ways to compensate for losses and to become more proficient at activities they want to perform well.

Selective optimization helps explain the variations in intellectual abilities just reviewed. As other research has found, when older adults are motivated to do well, few age-

Specialized LearningSpecialization works as follows. Suppose a man who was interested in one area of the world noticed that aging affected his vision and memory. He might compensate by buying reading glasses, increasing the type size on his computer, and keeping a file or notebook for whatever he reads about that area, sometimes rereading it. He might be selective, skipping over most of the news about other parts of the world. In that way, he would still know more about his particular specialty (optimization) than anyone else.

Selective optimization with compensation may be particularly crucial on the job, as older workers notice that some tasks now take longer or are more difficult for them to do. If they use compensation strategies, they are more likely to see opportunities for continued growth and improvement, making the job more interesting to them (Zacher & Frese, 2011).

An example that may be familiar to everyone is multi-

451

Selective optimization with compensation applies to every aspect of life, from choosing friends to playing baseball. Each adult seeks to maximize gains and minimize losses, choosing to practise some abilities and ignore others. Choices are critical because every ability can be enhanced or diminished, depending on how, when, and why a person uses it. It is possible to “teach an old dog new tricks,” but adults need to choose and practise the tricks.

Particularly relevant may be the selection of cognitive abilities. As Baltes and Baltes (1990) explain, selective optimization means that each person optimizes some intellectual abilities and neglects others. If the ignored abilities are the ones measured by IQ tests, then IQ scores fall. This would occur even though other abilities increase.

Selection and ActionSelective optimization is the probable explanation for the continued intellectual ability of adults. However, the concept is most easily demonstrated by brain activity that involves the motor system, not disembodied thinking (Beilock, 2010). For example, experienced typists scan more letters at a time to compensate for slower finger action, chefs prepare more foods in advance to avoid having multiple pots on the stove at once, and servers in restaurants use downtime to clear tables and prepare for new customers. Each of these occupations has been studied, with efficiency more apparent in experienced workers because of compensatory moves.

The most frequently studied action-

Thus, when star athletes are asked the secret of their success, they often do not know or remember because memory and emotion must shut down in order for professional expertise to focus solely on performance. According to a cognitive psychologist, “That’s why they usually thank God or their moms. They don’t know what they did, so they don’t know what else to say” (Beilock, quoted in Bascom, 2012).

Expert Cognition

Everyone can develop expertise, specializing in activities that are personally meaningful—

Culture and context guide all of us in selecting areas of expertise. Many adults born 60 years ago are much better than more recent cohorts at writing letters with distinctive but legible handwriting. Because of their childhood culture, they selected and practised penmanship, became expert in it, and maintained that expertise. On the other hand, younger adults grew up with various technological devices; some older adults are still cautious in programming everything from smart phones to video screens.

Experts, as cognitive scientists define them, are not necessarily those with rare and outstanding proficiency. Although sometimes the term expert connotes an extraordinary genius, to researchers it means more—

Expertise is not innate, nor does it always correlate with basic abilities (such as the five abilities measured in the Seattle Longitudinal Study). However, genetic predispositions may incline a person to be better at some skills than others. Expert language interpreters, for instance, might have been born with brain capacity to understand dialect, but they also need years of training and experience to become expert (Golestani et al., 2011).

452

EDVARD MARCH/CORBIS

MARILYNN K. YEE/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX

HERBERT SPICHTINGER/CORBIS

An expert is not simply someone who knows more about something, or who has done it often. At a certain tipping point, accumulated knowledge, practice, and experience become transformative, changing the brain, putting the expert in a different league (Ericsson, 2009; Wan et al., 2011). The quality as well as the quantity of cognition is advanced. Expert thought is: (1) intuitive, (2) automatic, (3) strategic, and (4) flexible, as we now describe.

Intuitive Novices follow formal procedures and rules. Experts rely more on their past experiences and on immediate contexts. Their actions are therefore more intuitive and less stereotypic. The role of experience and intuition is evident, for example, during surgery. Outsiders might think medicine is straightforward, but experts understand the reality:

Hospitals are filled with varieties of knives and poisons. Every time a medication is prescribed, there is potential for an unintended side effect. In surgery, collateral damage is inherent. External tissue must be cut to allow internal access so that a diseased organ may be removed, or some other manipulation may be performed to return the patient to better health.

[Dominguez, 2001]

453

In one study, many surgeons saw the same videotape of a gallbladder operation and were asked to talk about it. The experienced surgeons anticipated and described problems twice as often as did the residents (who had also removed gallbladders, just not as many) (Dominguez, 2001). Data on physicians indicate that the single most important question to ask a surgeon is, “How often have you performed this operation?” The novice, even with the best, most recent training, is less skilled than the expert.

Another study found that the number of years since a doctor was in medical school correlated negatively with proficiency (Choudhry et al., 2005). Obviously, when experience leads to habits that should change because of more recent advances, then simply having done something the same old way a thousand times does not mean that the task is performed better than it is by someone who uses a better technique, learned recently and performed only 50 times. Intuition arises from practice, but practice does not always lead to intuition.

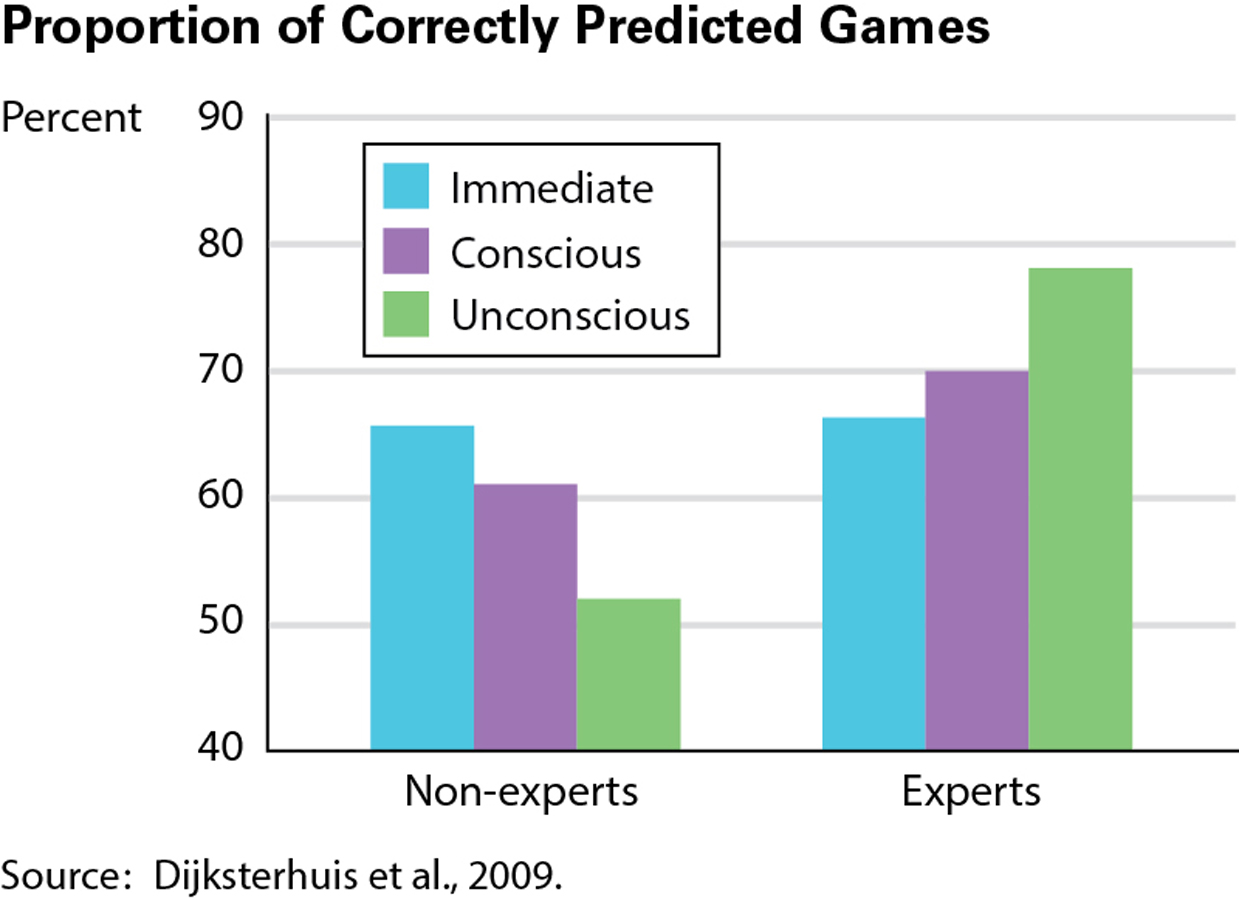

A different experiment that studied the relationship between expertise and intuition centred on predicting winners of several soccer matches, either instantly or after two minutes. College students who were avid fans made more accurate predictions when they had two minutes of unconscious thought (they were required to perform difficult math calculations and then give their answer) compared with when they had two minutes to mull over their choice (see Figure 12.5). In this, intuition trumped conscious thought. When given the same task, college students who didn’t care much about soccer (the non-

This experiment suggests that intuition, here occurring unconsciously, helps experts but not non-

AutomaticAutomatic processing is thought to be a crucial reason why expert chess and Go (a Chinese board game that requires the use of strategy) players are much better at the game than are novices. They see a configuration of game pieces and automatically encode it as a whole, rather than analyzing it bit by bit.

A study of expert chess players (aged 17 to 81) found minor age-

Many elements of expert performance are automatic. The complex action and thought required for performance have become routine, making it appear that most aspects of the task are performed instinctively. Experts process incoming information more quickly and analyze it more efficiently than do non-

In fact, some automatic actions are no longer accessible to the conscious mind. For example, adults are much better at tying their shoelaces than children are (adults can do it in the dark), but they are much worse at describing how they do it (McLeod et al., 2005). When experts think, they engage in automatic weighting of various non-

454

This may explain why, despite powerful motivation, quicker reactions, and better vision, teenagers have far more car accidents than middle-

Automaticity is particularly crucial if a person’s conscious mind is focused on something else, which is why many regions place restrictions on the number and age of passengers teen drivers are allowed to drive with (Zernike, 2012). Having passengers in the vehicle can be distracting, especially for new drivers. By contrast, adult drivers automatically ignore passengers when their unconscious alert system signals that focused attention is needed.

The relationship among expertise, age, and automaticity is not straightforward. Time is only one of the essential requirements for expertise. Not everyone becomes an expert over time (depending on the task), but everyone needs months—

Some researchers think practice must be extensive—

StrategicThe third characteristic of experts is that they have more and better strategies, especially when problems are unexpected (Ormerod, 2005). Indeed, strategy may be the most crucial difference between a skilled person and an unskilled one. Expert chess players not only have general strategies for winning, but they also have specific plans for the possibilities after a move—

Similarly, a strategy used by expert team leaders in the military and in civilian life is ongoing communication and reminders, especially during slow times. Consequently, when stress builds, no team member misinterprets the rehearsed plans, commands, and requirements. You have likely witnessed the same phenomenon in expert professors: They put well-

An intriguing study of age and strategy in job effectiveness comes from an occupation most everyone is familiar with: driving a taxi. In major cities, taxi drivers must find the best route (factoring in traffic, construction, time of day, and many other details), all while knowing where new passengers are likely to be found, as well as how to relate to customers, some of whom might want to chat, others not.

455

Research in London, England—

Of course, strategies themselves need to be updated as situations change—

In one study, pilots and non-

This does not mean, of course, that strategy always overcomes age deficits. In another study of pilots (aged 19 to 79) conducted with a flight simulator, the decision of whether to land in the fog involved more risk with increasing age, not the other way around. Older adult pilots had some strengths—

FlexibleFinally, perhaps because they are intuitive, automatic, and strategic thinkers, experts are also more flexible. The expert artist, musician, or scientist is creative and curious, deliberately experimenting, enjoying the challenge when things do not go according to plan (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996).

Consider the expert surgeon who takes the most complex cases and prefers unusual patients over typical ones because operating on them might bring sudden, unexpected complications. Compared with the novice, the expert surgeon is not only more likely to notice telltale signs (an unexpected lesion, an oddly shaped organ, a rise or drop in a vital sign) that may signal a problem, but is also more flexible and more willing to deviate from standard textbook procedures if those procedures prove ineffective (Patel et al., 1999).

456

Similarly, experts in all walks of life adapt to individual cases and exceptions—

Jenny, Again

The research on expertise focuses on job-

A dispassionate analysis of Jenny’s situation, from this chapter’s opening story, would conclude that another baby—

But statistics do not reflect Jenny’s intelligence, creativity, and practical expertise. She already knew how to access social support, evident by her seeking help. She was not daunted by her poverty; remember, she found many free activities for her children to enjoy, including sending them on vacation in the country. She was exceptional, but not unique: Many low-

Jenny used her knowledge well. She asked Billy, the father of the child, to be tested for sickle-

After she had the baby (a healthy, full-

When her baby was a little older, Jenny headed back to college, earning her BA on a full scholarship. Her professors recognized her intelligence: She was chosen to give the student speech at graduation. She then found work as a receptionist in a city hospital, a job that provided daycare and health benefits. That allowed her to move her family to a better neighbourhood of the Bronx.

Billy would sometimes visit Jenny and his daughter. His wife became suspicious and hired a detective to follow him—

457

The last time I saw her, I learned that she bikes, swims, and gardens every day. I met her son: He had earned a PhD in psychology, and both her daughters are also college graduates.

Not everyone becomes an expert in human relations. But one lesson from this chapter is that health, intelligence, and even wisdom may improve over the years of adulthood. As further explained in Chapter 13, adult choices made, and relationships tended, make a difference—

KEY Points

- Adults compensate for deficits, selecting what particular skills and abilities to optimize.

- Expertise is developed over the years as adults become more intuitive, automatic, strategic, and flexible in their thinking and actions regarding what task they have chosen as their specialty.

- Some people become experts in human relations, able to accurately assess their own abilities and the motivations of other people.