13.2 Intimacy

Every adult experiences the crisis Erikson called intimacy versus isolation, seeking to connect with other people. Specifics vary. Some adults are distant from their parents but close to partners and friends; others rely on family members but not on nonrelatives. The need for intimacy is universal yet dynamic: Each adult regulates closeness and reciprocity, combining friends, acquaintances, and relatives (Lang et al., 2009).

Everyone is part of a social convoy, a group of people who “provide a protective layer of social relations to guide, encourage, and socialize individuals as they go through life” (Antonucci et al., 2001). The term convoy originally referred to a group of travellers in hostile territory, such as soldiers marching across unfamiliar terrain. Individuals were strengthened by the convoy, sharing difficult conditions and defending one another.

As people move through life, their social convoy metaphorically functions as those earlier convoys did (Crosnoe & Elder, 2002; Lang et al., 2009). Paradoxically, current changes in the historical context (globalization, longevity, and ethnic and sexual diversity) make intimacy more vital. Humans need social convoys (Antonucci et al., 2007).

Friends and Acquaintances

Friends are crucial members of the social convoy, partly because they are chosen for the traits that make them reliable fellow travellers. They are usually about the same age, with similar experiences and values. Mutual loyalty and aid are expected from friends: A relationship that is imbalanced (one person always giving, the other always taking) over the years is likely to end because both parties are uneasy. Of course, sometimes a friend needs care and cannot reciprocate at the time. Friends provide practical help and useful advice when serious problems—

468

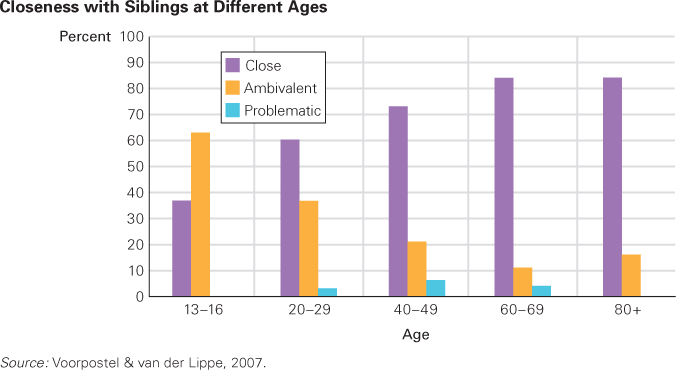

Friendship and Human DevelopmentA comprehensive study found that friendships improve with age. To be specific, adolescents and young adults consider a significant minority of their friendships ambivalent or problematic. By adulthood, most friendships are rated close, few are ambivalent, and almost none are problematic (Fingerman et al., 2004).

Close friends offer companionship, information, and laughter in daily life. They encourage one another during challenging periods, helping with mental health. One reason depression seems to decrease with age is that friends are more carefully selected, and friendships are more nourished, so that friends become more supportive over time.

Friends help with details of physical health as well, encouraging one another to eat better, quit smoking, exercise, and so on. The reverse is also true: If someone gains weight over the years of adulthood, his or her best friend is likely to do so as well. In fact, although most adults keep their friends for decades, health habits are one reason some adults change friends (O’Malley & Christakis, 2011). For instance, a friendship between a chain smoker and someone who quit smoking is likely to fray.

If an adult has no friends, health suffers (Couzin, 2009). This seems as true in developing nations as in developed ones. Universally, humans are healthier with supportive friends and relatives, and sicker when they are socially isolated (Kumar et al., 2012).

AcquaintancesIn addition to friends, hundreds of other acquaintances provide information, support, social integration, and new ideas (Fingerman, 2009). Neighbours, co-

Among the consequential strangers in your life might be

- dog owners you meet when you walk your dog

- the barber or hair stylist who regularly cuts your hair

- the coffee shop staff from whom you buy a muffin every day

- your friend’s parents.

A consequential stranger may also be an actual stranger, such as someone who sits next to you on an airplane, or directs you when you are lost, or gives you a seat on the bus. Such acquaintances differ from most close friends and family members in that they include people of diverse religions, ethnic groups, ages, and political opinions (Fingerman, 2009). The Internet has strengthened friendships and added more consequential strangers to many people’s lives (Stern & Adams, 2010; Wang & Wellman, 2010).

Regular acquaintances are part of each person’s peripheral social network. With age, the number of such peripheral friends decreases. For example, one study found that the average emerging adult had 16 peripheral friends, but the average middle-

469

The composition of social networks varies by culture. In many African nations, everyone in the community is in the peripheral network. They might stop by, unannounced, to visit, which in other cultures might be considered rude. Another cultural difference is whether family members are considered friends. For example, one study found that in both Germany and Hong Kong, adults had about the same number of intimates, but the Germans tended to include more non-

Family Bonds

Close friends often are referred to as being “like a sister” or “my brother.” Such terms reflect the assumption that family connections are intimate. As just mentioned, this is more reflective of some cultures than of others, but family relationships are crucial for many adults, usually more so as they age.

Which particular family members become intimates varies for many reasons, as one might expect. One intriguing study of the population of Denmark found that twins married less often than single-

Adult Children and Their ParentsAlthough most adults in modern societies leave their parents’ homes to establish their own households, a study of 7578 adults in seven nations found that physical separation did not necessarily weaken family ties. In fact, these authors concluded that intergenerational relationships are becoming stronger, not weaker, as more adult children live apart from their parents (Treas & Gubernskaya, 2012). This bond is sometimes financial as well as emotional. In many nations, young adults who leave home to find work send most of their salary back home. Personal goals are sacrificed for family concerns, and “collectivism often takes precedence and overrides individual needs and interests” (Wilson & Ngige, 2006).

Other research points to the fact that the relationship between parents and adult children tends to be less affectionate if they live together (Ward & Spitze, 2007). This may be correlation rather than cause, since intergenerational living may come about when either the parents or the children are unable to live independently.

Overall, parents usually provide more financial and emotional support to their adult children than vice versa, although most children rally if necessary. In assessing intimacy, it should be noted that whenever adult children have serious financial, legal, or marital problems, most parents try to help. This has always been evident for young, single adults, but the economic recession has led to an increasing number of 25-

Siblings and Other RelativesWith adulthood often comes marriage and childbearing, both of which can potentially increase the closeness between siblings or enhance previous difficulties (Conger & Little, 2010). The potential for closeness is greater when nieces and nephews are born. Parents want their children to know their aunts, uncles, and cousins, and that reduces sibling distance. Furthermore, adulthood frees siblings from forced cohabitation and rivalry, allowing them to differ without fighting.

470

Adult siblings often help one another, providing practical support (especially between brothers) and emotional support (especially between sisters) (see Figure 13.2) (Voorpostel & van der Lippe, 2007). For example, a middle-

I have a good relationship with my brothers.…Every time I come, they are very warm and loving, and I stayed with my brother for a week.…Sisters is another story. Sisters are best friends. Sisters is like forever. When I have a problem, I phone my sisters. When I’m feeling down, I phone my sisters. And they always pick me up.

[quoted in Connidis, 2007]

In several South Asian nations, brothers are obligated to bestow gifts on their sisters, who in turn are expected to cook for and nurture their brothers (Conger & Little, 2010). Such patterns may impede individual growth, but they reduce poverty and strengthen family bonds. By encouraging siblings to care for one another, they satisfy intimacy needs.

A large study in the Netherlands found a curious relationship between closeness to parents and closeness among siblings. As expected, when adult women were close to their parents, they also were close to their siblings. To some extent, this was true for the men as well. However, those brothers who were distant from their parents tended to be closer than average to their siblings, as if to compensate. One family link becomes stronger because another one is weak (Voorpostel & Blieszner, 2008).

Getting AlongTime and again, researchers have found that adults who have separate households from other adults in their family are nevertheless profoundly affected by their relationships with these family members. Such relationships can be supportive, as mentioned above, or destructive. Often they are both; ambivalence in parent–

In one international study, older adults (average age of 77) were asked how they got along with a particular child (average age of 53) (Silverstein et al., 2010). Answers were clustered into four groups: amicable (close, got along well, high communication), detached (distant, low communication), disharmonious (conflict, critical, arguing), and ambivalent (both close and critical, high communication).

471

All of the six nations studied had some elders in each of the four clusters, with amicable relationships being the most common. National differences were evident in the frequency of each cluster, with England and Norway being the most amicable, Germany and Spain the most detached, and Israel the most ambivalent. No nation had many disharmonious relationships, but the United States had more (20 percent) than the other five nations (Silverstein et al., 2010). Frail and dependent elders were more likely to experience friction, even though they often lived with their children. Close and affectionate family relations were most likely when the government provided many services (e.g., health care, senior residences). This suggests again that emotional intimacy is a distinct need for adults, independent of practical necessity.

Back to the interplay of friends and relatives: In every nation, most family members support each other. However, some adults stay distant from their blood relatives because they find them toxic. Such adults may become fictive kin in another family. They are not technically related (hence fictive), but are accepted and treated like a family member (hence kin). If adults have difficult relationships with their original family or if they are far from home, fictive kin can be a lifeline (Ebaugh & Curry, 2000; Heslin et al., 2011; Kim, 2009; Muraco, 2006).

Committed Partners

As detailed earlier, people in many nations take longer than previous generations did to publicly commit to one long-

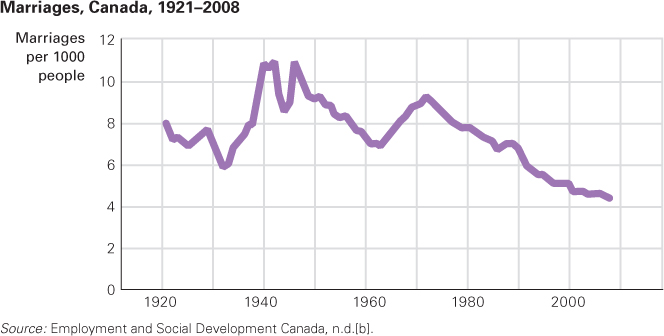

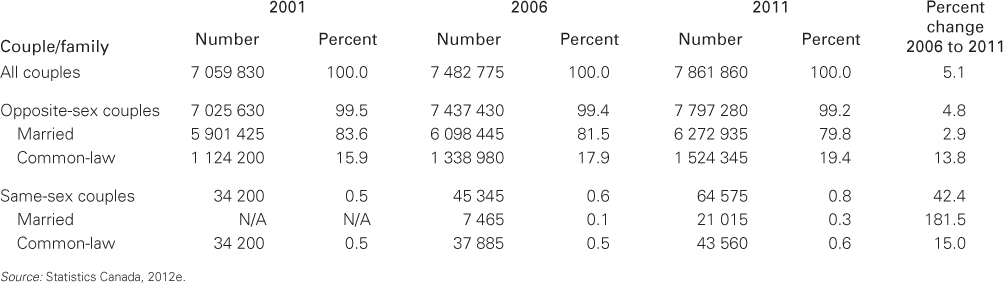

Recent longitudinal Canadian data indicate that in 1961, married couples represented 91.6 percent of census families, but by 2011, this proportion had significantly declined to 67.0 percent. This decrease may be partly due to the increased number of common-

OBSERVATION QUIZ

What are some possible reasons for the increase in marriage rates in the 1940s and again in the 1970s?

The fluctuations in the rates of marriages over the years are most likely due to historical events. For example, the increased number of marriages in the 1940s is due to the end of World War II, and the increase in the 1970s is due to the large number of baby boomers reaching adulthood.

In other nations, less than 2 percent of the population stays single for life. However, cohort matters. In Canada after the Depression, in the first couple of years of World War II (1940–

DAVE REEDE/AGSTOCK IMAGES/CORBIS

Marriage and HappinessFrom a developmental perspective, marriage is a useful institution. Adults thrive if another person is committed to their well-

From an individual perspective, the consequences are more mixed. There is no doubt that a satisfying marriage improves health, wealth, and happiness, but some marriages are not satisfying (Fincham & Beach, 2010). Generally, married people are a little happier, healthier, and richer than never-

472

A 16-

Another large longitudinal study of married adults found that

there were as many people who ended up less happy than they started as there were people who ended up happier than they started (a fact that is particularly striking given that we restricted the sample to people who stayed married).

[Lucas et al., 2003]

Thus, most adults marry and expect ongoing happiness because of it, but some will be disappointed (Coontz, 2005). Those who never marry can be quite happy as well (DePaulo, 2006).

Cohabitation historically has led to less happy adults than has marriage, especially for women. However, this also is changing by cohort and varies by culture, with some places finding few significant differences between cohabiting and married couples, or between men and women (Stavrova et al., 2012). Researchers now realize that cohabiters who expect to marry are quite different from those who choose to live together without expectation of marriage. If the latter couple eventually marries, their chances of a happy marriage are less than average (Sassler et al., 2012).

For many cohabiters, living together is the first step in commitment and mutual trust. The next step is the wedding, and then each year of marriage increases their public and personal commitment to each other. Divorce becomes less likely, and many signs indicate that they are a couple, not just two individuals. For instance, they have more children than cohabiters who did not intend to marry, the man earns more than comparable unmarried men, and the woman spends more time on household tasks (Kuperberg, 2012).

A sizable number of adults have found a third way to have a steady romantic partner, called living apart together (LAT). They have separate residences, but especially when the partners are older than 30, LATs may be committed to each other, perhaps functioning as a couple for decades (Duncan & Phillips, 2010).

There are many ways to understand love, cross-

473

Among twenty-

Partnerships Over the YearsNot surprisingly, a meta-

The passage of time also makes a difference. For instance, the honeymoon period tends to be happy, but soon frustration increases because conflicts arise (see At About This Time). Intimate partner violence is more likely in the first years of a relationship than later on (H. K. Kim et al., 2008). Partnerships (including heterosexual married couples, committed cohabiters, same-

Gradually, after a decade or two of declining satisfaction, partnerships improve (Scarf, 2008). Part of the explanation is that many unhappy relationships end after a few years; this is particularly true for cohabiters, who have fewer barriers to separation. Generally, those who continue to be committed learn to appreciate each other, avoiding the flash points that previously caused fights.

Contrary to outdated impressions, the empty nest (the time when parents are alone again after their children have moved out and launched their own lives) often improves a relationship (Gorchoff et al., 2008). Simply spending time together, without interruptions from infants, demands from children, or rebellions from teenagers, improves intimacy as partners can focus on each other’s needs. However, if couples have stayed together because of the children, the empty nest stage can become a time of conflict or divorce.

When all the children have become independent, long-

Marital Happiness over the Years

| Interval After Wedding | Characterization |

|---|---|

| First 6 months | Honeymoon period— |

| 6 months to 5 years | Happiness dips; divorce is more common now than later in marriage |

| 5 to 10 years | Happiness holds steady |

| 10 to 20 years | Happiness dips as children reach puberty |

| 20 to 30 years | Happiness rises when children leave the nest |

| 30 to 50 years | Happiness is high and steady, barring serious health problems |

Aside from the impact of freedom and income, some troubled relationships rebound to earlier levels of satisfaction as mates learn to understand and forgive one another (Fincham et al., 2007). However, much depends on context: The process of forgiveness can help or harm a relationship, depending on the characteristics of the relationship (McNulty & Fincham, 2012). Shared backgrounds, values, and interests (homogamy) reduce conflict, whereas different backgrounds (heterogamy) raise issues that were not expected.

474

Marriages among people of different ethnic groups increased more than 20-

Time may help repair a relationship, but sometimes new stressors occur. Economic stress causes marital friction no matter how many years a couple has been together (Conger et al., 2010), and contextual factors can undermine a couple’s willingness to communicate and compromise (Karney & Bradbury, 2005). A long-

Every generality obscures specifics. Some long-

Gay and Lesbian PartnersAlmost everything just described applies to gay and lesbian partners as well as to heterosexual ones (Biblarz & Savci, 2010; Herek, 2006). Some same-

Political and cultural contexts for same-

According to Statistics Canada, the last census reported 64 575 same-

Current research with a large, randomly selected sample of people in gay or lesbian marriages in North America is not yet available. Many studies are designed to prove that same-

Divorce And SeparationThroughout this text, developmental events that seem isolated, personal, and transitory are shown to be interconnected and socially mediated, and to have enduring consequences. Relationships never improve or end in a vacuum; they are influenced by the social and political context (Fine & Harvey, 2006). Divorce, separation, and the end of a cohabiting relationship are all affected by time and circumstances (see TABLE 13.3).

|

Before Marriage Divorced parents Either partner under age 21 Family opposed Cohabitation before marriage Previous divorce of either partner Large discrepancy in age, background, interests, values (heterogamy) During Marriage Divergent plans and practices regarding child- Financial stress, unemployment Substance abuse Communication difficulties Lack of time together Emotional or physical abuse Unsupportive relatives In the Culture High divorce rate in cohort Weak religious values Laws that make divorce easier Approval of remarriage Acceptance of single parenthood |

475

Divorce occurs because at least one half of a couple believes that he or she would be happier not married. According to General Social Survey data, 7 percent of the total Canadian population aged 15 and older in 2006 was divorced. In addition, about 13 percent of the population had experienced at least one divorce, and nearly half had remarried (Beaupré, 2008).

The Marriage Option Canada legalized same-

The divorce rate in Canada peaked at 50.6 percent in 1987 after a change in the Divorce Act in 1986 allowed individuals to file for divorce after one year of separation (instead of three years). Since 2008, the divorce rate has ranged between 35 to 42 percent. For example, in 2008, 40.7 percent of marriages were projected to end in divorce. The highest divorce rate was in the Yukon (59.7 percent) and the lowest was in Newfoundland and Labrador (25.0 percent) (Employment and Social Development Canada, n.d.[b]). With each subsequent marriage, the odds of divorce increase.

Typically, people divorce because some aspects of the marriage have become difficult to endure, yet divorce often presents a new set of challenges, including reduced income, lost friendships (many couples have only other couples as friends), and weakened relationships with the children. Weakened relationships occur immediately—

Family problems arise not only with children, but also with other relatives. The divorced adult’s parents may be financially supportive, but they may also be emotionally critical that their child’s marriage did not work out. Some married adults have good relationships with some of their in-

Although divorce is finalized on a particular day, from a developmental perspective it is a process that begins years before the official decree and reverberates for decades after (Amato, 2010). Income, family welfare, and self-

Some research finds that women suffer from divorce more than men do (their income, in particular, is lower), but men’s intimacy needs are especially at risk. Some husbands rely on their wives for companionship and social interaction; they are unaccustomed to inviting friends over or chatting on the phone. Divorced fathers are often lonely, alienated from their adult children and grandchildren (Lin, 2008a).

476

If divorce ends an abusive, destructive relationship (as it does about one-

Re-

Usually, both former partners in a severed relationship attempt to re-

Divorced adults who do not plan to remarry often develop new romantic partnerships, on average within two years of divorce. Rates of re-

Initially, remarriage restores intimacy, health, and financial security. For remarried fathers, bonds with their new stepchildren or with a new baby may replace strained relationships with their children from the earlier marriage. Divorce usually increases depression and loneliness; re-

Most remarried adults are quite happy immediately after the wedding (Blekesaune, 2008). However, their happiness may not endure. Remember that personality tends to change only slightly over the life span; people who were chronically unhappy in their first marriage may also become unhappy in their second. Stepchildren add unexpected stresses (Sweeney, 2010), and stepparents have difficulty letting the spouse’s former mate continue to care for their own children (Gold, 2010). One theory is that because expectations are not clear about the proper role of step-

Remember, however, that each cohort develops in a distinct historical period, and the context of divorce has changed over the past decades. As more people separate or divorce, more people find suitable new partners and more stepchildren and stepparents have friends who have experienced the same problems and who can help with adjustment.

477

One specific cohort change is that contemporary adults have more friends of both sexes than was true 50 years ago. If they get divorced, that friendship network may buffer them from the loneliness and loss of intimacy that divorced adults once experienced. Research on older adults who are divorced makes staying married seem best, on average, but that research may not predict the future for 30-

KEY Points

- Friends and consequential strangers are part of the social convoy that helps adults navigate happily through the years.

- Family connections remain important, especially between parent and adult child and between siblings.

- Happiness in marriage ebbs and flows, with highs in the first months of a new relationship and lows when children are very young.

- Divorce is almost always difficult; remarriage can bring new happiness and new problems.