13.3 Generativity

According to Erikson, after the stage of intimacy versus isolation comes the stage of generativity versus stagnation, when adults seek to be productive in a caring way. Without generativity, adults experience “a pervading sense of stagnation and personal impoverishment” (Erikson, 1963).

Adults satisfy their need to be generative in many ways, especially through art, caregiving, and employment. Of these three, the link between artistic expression and generativity has been least studied (although creativity is recognized as an avenue for self-

Parenthood

Although generativity can take many forms, its chief form is establishing and guiding the next generation, usually through parenthood (Erikson, 1963). Many adults pass along their values as they respond to the hundreds of requests and unspoken needs of their children each day, thus becoming generative.

Parenting has been discussed many times in this text, primarily with a focus on its impact on children. Now we concentrate on the adult half of this interaction—

Adults who choose parenthood willingly cope with the many stresses that come with that role. As Erikson (1963) says, “The fashionable insistence on dramatizing the dependence of children on adults often blinds us to the dependence of the older generation on the younger one” (p. 266).

478

Children sometimes reorder adult perspectives, as adults become less focused on their personal identity or intimate relationships. One sign of a good parent is the parent’s realization that the infant’s cries are communicative, not selfish, and that adults need to care for children more than vice versa (Katz et al., 2011). This generative response does not always happen in the way that developmentalists would prefer. For example, a study of 91 gang members who became fathers found that almost all of them expressed new pride and priorities, but few quit their gangs and law-

Every parent is tested by the dynamic experience of raising children. Many parents learn that, just when adults think they have mastered the art of parenting, children become older, thus presenting new challenges. Over the decades of family life, babies arrive and older children grow up, financial burdens shift, income almost never seems adequate, and, if the family includes several children, seldom is every child thriving. Illness and disability require extra care. Problems and stresses increase as family size increases. This is true worldwide, at least until the children are grown (Margolis & Myrskylä, 2011). As already mentioned, adult children usually bring their parents more joy than distress, but if even only one of them is troubled, middle-

Chapter 8 explained that children can develop well in any family structure—

Grandparenthood can be another source of generativity and intimacy, depending on national policies and customs, gender, parent–

Foster ChildrenParent-

479

Step-

Yet, children may benefit from a step-

AdoptionMost adoptions in Canada are “open,” which means that the adoptive parents and the birth mother have a relationship with each other and exchange information. The amount of information that is exchanged depends mostly on the closeness of the relationship between the two parties. The advantages of an open adoption are that the birth mother has more input into the adoption process, and the needs of the child are more readily met.

In any given year, there are about 78 000 children in Canada waiting for adoption. In addition, about 2000 international children are adopted in Canada every year. Most overseas adoptions are not open since the birth parents are mostly not involved in the adoption process, and are often not known. As of 2010, the most common country from which children were adopted was China (see TABLE 13.4). Other countries from which Canadians adopted children include Haiti, the United States, Vietnam, and Russia (Adoption Council of Canada, 2011). One reason for the popularity of adoptions from China is the large number of baby girls available for adoption due to that country’s one-

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 431 | 451 | 472 |

| Haiti | 147 | 141 | 172 |

| U.S. | 182 | 253 | 148 |

| Vietnam | 111 | 159 | 139 |

| Russia | 91 | 121 | 102 |

| South Korea | 98 | 93 | 98 |

| Philippines | 118 | 86 | 88 |

| Ethiopia | 187 | 170 | 63 |

| Colombia | 53 | 41 | 62 |

| India | 54 | 59 | 55 |

| All countries | 1 915 | 2 122 | 1 946 |

| Source: Adoption Council of Canada, 2011. | |||

Strong parent–

Strong bonds may be stressed in adolescence, when teenagers may want to know more about their genetic and ethnic roots. One college student who feels well loved and cared for by her adoptive parents explains:

In attempts to upset my parents sometimes I would (foolishly) say that I wish I was given to another family, but I never really meant it. Still when I did meet my birth family I could definitely tell we were related—

[April, 2012, personal communication]

480

Attitudes in the larger culture often increase tensions between adoptive parents and children. For example, the mistaken notion that the “real” parents are the biological ones is a common social construction that hinders a secure attachment.

An important factor to consider when adopting children from overseas or from North America is race. Adoptive children are often of a different race and/or culture than their adoptive parents. It is helpful to expose adopted children who are of a different ethnicity to experiences, customs, and history unique to that ethnicity, to help children establish their ethnic identity.

All the details already explained in this text, from the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (Chapter 2) to the first words (Chapter 3), from theory of mind (Chapter 5) to learning to read (Chapter 7), are accomplishments celebrated by an astute parent—

Caregiving

Erikson (1963) wrote that a mature adult needs to feel needed. Some caregiving requires meeting physical needs—

The time and energy required to provide emotional support to others must be reconceptualized as an important aspect of the work that takes place in families…Caregiving, in whatever form, does not just emanate from within, but must be managed, focused, and directed so as to have the intended effect on the care recipient.

[Erickson, 2005]

Thus, caregiving includes responding to the emotions of people who need a confidant, a cheerleader, a counsellor, or a close friend. Parents and children care for one another, as do partners. Often neighbours, friends, and more distant relatives are caregivers as well.

Most extended families include a kinkeeper, a caregiver who takes responsibility for maintaining communication. The kinkeeper gathers everyone for holidays; spreads the word about anyone’s illness, relocation, or accomplishments; buys gifts for special occasions; and reminds family members of one another’s birthdays and anniversaries (Sinardet & Mortelmans, 2009). Guided by their kinkeeper, all the family members become more generative.

Fifty years ago, kinkeepers were almost always women, usually the mother or grandmother of a large family. Now families are smaller and gender equity is more evident, so some men or young women can be kinkeepers. Generally, however, the kinkeeper is still a middle-

Caring For Older and Younger GenerationsBecause of their position in the generational hierarchy, many middle-

481

Caregiving is beneficial because people feel useful when they help one another. Far from being squeezed, older adults are less likely to be depressed if they are supporting their adult children than when they are distant from them (Byers et al., 2008). On their part, many grown children get pleasure from helping their parents. For instance, researchers find that young adults often help their parents understand current culture and technological change, providing information and insight.

Many middle-

Because of better health and vitality throughout life, many adults do not need to provide extensive physical care for older generations. Specifics of elder care differ (see TABLE 13.5). As we will explain in detail in Chapter 15, in developed nations when elders need care, it is typically provided by a spouse or a paid caregiver. Adult children and grandchildren are part of the caregiving team, but not the major providers.

| Phone Calls per Month | Visits per Month | Minutes of Help per Week | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wife to own parents | 11 | 6 | 120 |

| Husband to wife’s parents | 8 | 5 | 70 |

| Total to wife’s parents | 19 | 11 | 190 |

| Husband to own parents | 7 | 4 | 100 |

| Wife to husband’s parents | 5 | 4 | 58 |

| Total to husband’s parents | 12 | 8 | 158 |

| Source: E. Lee et al., 2003. | |||

For a minority of adults—

Culture and Family CaregivingFamily bonds depend on many factors, including childhood attachments, cultural norms, and the financial and practical resources of each generation. Some cultures assume that elderly parents should live with their children; others believe that elders should live alone as long as possible and then enter a care-

Elder Care Connections between middle-

In North America, Western Europe, and Australia, older adults cherish their independence and dread burdening their children. Even frail parents seek to maintain autonomy, feeling that moving in with their children is a sign of failure. By contrast, in nations where interdependence is a desirable personality trait, living with family does not necessarily signify a problem (Harvey & Yoshino, 2006).

482

Ethnic variations are evident in how close family members are expected to be. Generally, ethnic minorities are more closely connected to family members than are ethnic majorities in that they see each other more often and share food, money, and so on. However, although people may assume that closeness means affection, for minorities particularly, closeness sometimes increases conflict (Voorpostel & Schans, 2011). Ethnic variation is also evident in arrangements for caring for older family members. For instance, most elderly Chinese have their own homes; however, if they live with an adult child, in mainland China it is usually with a son, but in Taiwan it is usually with a daughter (Chu et al., 2011).

Employment

Besides family caregiving, the other major avenue for generativity is employment. Most of the social science research on jobs has focused on economic productivity, an important issue but not central to our study of human development. Social scientists, in economics and in other disciplines, are beginning to include working as part of broader psychological theory and practice (Blustein, 2006).

As is evident from many of the terms used to describe healthy adult development, such as generativity, success and esteem, instrumental, and achievement, adults have many psychosocial needs that employment can fill. The converse is also true: Unemployment is associated with higher rates of child abuse, alcoholism, depression, and many other social and mental health problems (Freisthler et al., 2006; Wanberg, 2012). In addition, a longitudinal Canadian study indicated that unemployed men and women had an elevated risk of mortality from accidents, violence, and chronic diseases (Mustard, Bielecky, et al., 2013). Another study found that American adults who can’t find work are 60 percent more likely to die than other people their age, especially if they are younger than 40 (Roelfs et al., 2011).

Working For More Than MoneyIncome pays living expenses, but it also does far more than that. It allows people to buy items that they desire, move to safer neighbourhoods, and live healthier and safer lives. However, to understand human development, we must go beyond income and consider the generative aspects of work—

- develop and use their personal skills

- express their creative energy

- help and advise co-

workers as a mentor or friend - support the education and health of their families

- contribute to the community by providing goods or services.

The pleasure of “a job well done” is universal, as is the joy of having supportive supervisors and friendly co-

483

A developmental view finds that extrinsic rewards tend to be more important at first, when young people enter the workforce and begin to establish their careers (Kooij et al., 2011). After a few years, in a developmental shift as an individual ages, the intrinsic rewards of work become more important” (Sterns & Huyck, 2001).

The power of intrinsic rewards explains why older employees display, on average, less absenteeism, less lateness, and more job commitment than do younger workers (Landy & Conte, 2007). A crucial factor may be that in many jobs, older employees have more control over what they do, as well as when and how they do it. Autonomy reduces strain and increases dedication and vitality. Autonomy is also seen as an important part of intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Another crucial factor is family support. Family members being appreciative and helpful regarding a worker’s job requirements benefits the person’s health. Satisfaction at work spills over to satisfaction at home and vice versa. For example, when health impairs a husband’s ability to work, divorce is more likely (Teachman, 2010).

The Changing Workplace

Obviously, work is changing in many ways. Globalization means that each nation exports what it does best (and cheapest) and imports what it needs. Specialization, interdependency, and international trade are increasing. Advanced nations are shifting from industry-

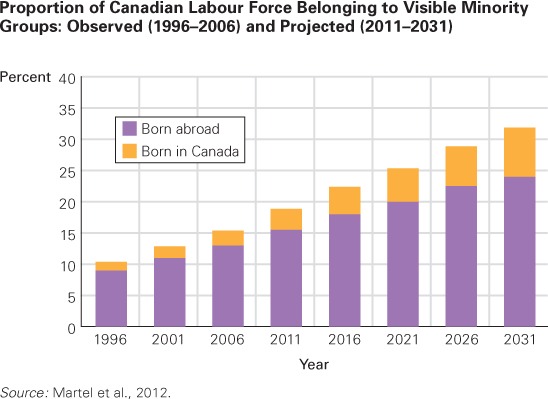

DiversityDramatic changes have occurred in who has a job and what they do. This is true in every nation, but we provide statistics for Canada as an obvious example. About 40 years ago, women accounted for 39.1 percent of the labour force; in 2009, women accounted for 58.3 percent of the Canadian workforce (Statistics Canada, 2011f). In 1996, 10 percent of the labour force belonged to a visible minority group; by 2006, this had increased to 15 percent (Martel et al., 2012). Of this group, an increasing number were born in Canada rather than having immigrated here.

In terms of salary, in 1980, recent immigrants earned much less than their Canadian-

On average over this 25-

Immigrants from different countries experience different rates of employment in Canada (see Figure 13.4). From 2001 to 2006, immigrants born in Southeast Asia experienced similar employment and unemployment rates as the Canadian-

ESPECIALLY FOR Entrepreneurs Suppose you are starting a business. In what ways would middle-

Middle-aged adults are beneficial as employees and as customers. Middle-aged workers are steady, with few absences and good “people skills,” and they like to work. In addition, household income is likely to be higher at about age 50 than at any other time, so middle-aged adults will probably be able to afford your products or services.

As mentioned above, diversity in the workplace also exists in terms of who does what job. Historically, specific occupations have been far more segregated by sex and ethnicity than they are today; for example, male nurses and female police officers were very rare in 1960 but are much more common today. Employment discrimination in gender and ethnicity is still present—

484

Changing JobsOne recent change in the labour market is that resignations, firings, and tarings occur more often. Temporary employees are also more common, as are career and job changes. It is estimated that Canadian workers will have, on average, about three careers and eight jobs over their employment life (Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, 2011). Similarly, between the ages of 23 and 44, the average worker in the United States has seven different employers, with men somewhat more likely to change jobs than women (U.S.Bureau of the Census, 2011b). Sometimes jobs are lost because employers downsize, reorganize, relocate, outsource, or merge. Sometimes adults choose to quit because of dissatisfaction or frustration.

No matter the reason for job loss, when it occurs social connections to consequential strangers are broken and workers suffer. These human costs are confirmed by longitudinal research: People who frequently changed jobs by age 36 were three times more likely to have various health problems by age 42 (Kinnunen et al., 2005). This study controlled for smoking and drinking; if it had not, the health impact would have been even greater, since poor health habits correlate with job instability.

As adults grow older, job changes become increasingly stressful, for several reasons (Rix, 2011):

- Seniority brings higher salaries, more respect, and greater expertise; workers who leave a job they have had for years lose these advantages.

- Many skills required for employment were not taught decades ago, and many employers are reluctant to hire and train older workers.

- Age discrimination is illegal, but workers are convinced that it is common, especially after age 50. Even if this is not true, we know from stereotype threat that it undercuts success in job searches.

- Relocation reduces both intimacy and generativity.

From a developmental perspective, this last factor is crucial. Imagine that you are a middle-

If you were unemployed and in debt, and a new job was guaranteed, you might leave your friends and your community. But would your spouse and children quit their jobs, schools, and social networks to move with you? For you and everyone in your family, moving means losing intimacy.

Such difficulties are magnified for immigrants. Many depend on other immigrants for housing, work, and social support (García Coll & Marks, 2011). That meets some intimacy and generativity needs, but obviously any move decreases a person’s chance to have friends, family, and employment that enhance psychological and physical health.

485

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Accommodating Diversity

Accommodating the various sensitivities and needs of a diverse workforce requires far more than reconsidering the cafeteria menu and the holiday schedule. Private rooms for breastfeeding, revised uniform guidelines, better office design, and new management practices may be required. Exactly what is needed depends on the particular culture of the workers: Some are satisfied with conditions that others would reject. For example, one study found that U.S. employees were stressed when they had little control over their work or when they had direct confrontations with their supervisors, whereas employees in China were most stressed by the possibility of negative job evaluations and indirect conflicts with co-

Some words, policies, jokes, or mannerisms may seem innocuous to people of one group but toxic to people of another group. Researchers have begun to explore micro-

Micro-

Consider one study in detail. African-

After reading the transcripts, the participants took a test that required mental concentration. The performance of the European-

The experimenters believe that this result shows that the African-

Work SchedulesNo longer does work always follow a 9-

One crucial variable for job satisfaction is whether employees can choose their own hours, particularly when it comes to working overtime. Workers who volunteer for paid overtime are usually satisfied, but workers who are required to work overtime are not (Beckers et al., 2008). This is true no matter how experienced the workers are, what their occupation is, or where they live. For instance, a nationwide study of 53 851 American nurses, ages 20 to 59, found that required overtime was one of the few factors that reduced job satisfaction in every cohort (Klaus et al., 2012). Similarly, a study of office workers in China found that the extent of required overtime correlated with less satisfaction and poorer health (Houdmont et al., 2011). Apparently, although work (paid or unpaid) is satisfying to every adult, working too long and not by choice undercuts the psychological and physical benefits.

486

Weekend work, especially with mandatory overtime, is particularly difficult for parent–

One attempt to provide more worker choice is flextime, which gives employees some choice in the particular hours they work. Some form of flex-

Such schedules have many advantages for employees and employers. However, while they allow workers to have the benefits of greater family enrichment, the concurrent demands of family life and work can increase stress (Bianchi & Milkie, 2010; Golden et al., 2006).

In theory, part-

About one-

Combining Intimacy and Generativity

Adult development depends on particulars of job, home, and personality that affect the ability to balance intimacy and generativity (Voydanoff, 2007). Employment contributes to adult psychosocial health, but other factors are important as well: Some adults are happy without a job, especially if others in their household are employed, with adequate income.

A large study of adult Canadians found that about half of the variation in their distress was related to employment (working conditions, support at work, occupation, job security), but at least as much was related to family (having children younger than age 5, support at home) and feeling personally competent (Marchand et al., 2012).

To find an ideal balance, at least three factors are helpful: adequate income, chosen schedules, and social support. For new parents in Canada, employment insurance (EI) is key. EI provides benefits for mothers and fathers who are expecting, will be giving birth, are adopting a child, or are caring for a newborn. A maximum of 35 weeks of parental benefits is available to biological or adoptive parents, which can be shared between the two parents. To be eligible, the parent must have paid EI premiums, accumulated at least 600 hours of insurable employment, and had his or her normal weekly earnings reduced by more than 40 percent (Government of Canada, 2014).

487

MONALYN GRACIA/CORBIS

When parents have children, they adjust their work and child-

In many ways, family members adjust to one another’s employment, helping everyone cope. They may recognize that men, women, and children can be better off with today’s dual-

From a developmental perspective, it is clear that intimacy and generativity continue to be important to adults, as they always have been. As you will see in Chapters 14 and 15, many perspectives are possible on late adulthood as well. Some view the last years of life with dismay, while others consider them the golden years. Neither view is quite accurate.

KEY Points

- Adults strive to meet their generativity needs, primarily through raising children, caring for others, and being productive members of society.

- Parenthood of all kinds is difficult yet rewarding, with foster, step-

, and adoptive parents facing additional challenges. - Caregivers are generative, with each adult caring for other family members.

- Employment ideally aids generativity, via productivity and social networks.

- Many parents seek to combine child-

rearing and employment, with mixed success, depending on the specifics of employment and family life.

488