14.1 Prejudice and Predictions

SEONGJOON CHO/LONELY PLANET IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES

Prejudice about late adulthood is common among people of all ages, including young children and older adults. That is a reflection of ageism, the idea that age determines who you are. Ageism can target people of any age. Why do people accept it, especially in regard to the old?

494

One expert contends that “there is no other group like the elderly about which we feel free to openly express stereotypes and even subtle hostility.…[M]ost of us…believe that we aren’t really expressing negative stereotypes or prejudice, but merely expressing true statements about older people when we utter our stereotypes” (Nelson, 2011). As mentioned above, even older people express these stereotypes. If an older person forgets something, he or she might claim a “senior moment,” not realizing the ageism of that reaction. When hearing an ageist phrase, such as “second childhood,” or a patronizing compliment, such as “spry” or “having all her marbles,” elders themselves miss the insult. The expert believes that a major problem is that ageism is institutionalized in our culture, evident in the media, employment, and retirement communities.

Another reason people accept ageism is that it often seems complimentary (“young lady”) or solicitous (Bugental & Hehman, 2007). However, the effects of ageism, whether benevolent or not, are insidious. They seep into the older person’s feelings of competence; the resulting self-

Believing the Stereotype

When families are confronted with racism or sexism, parents teach their children to recognize and counter bias, while encouraging them to be proud of who they are. However, when children believe an ageist idea, few people teach them otherwise. Later on, their longstanding prejudice is very difficult to change, undercutting their own health and intellect (Golub & Langer, 2007).

The positive and negative stereotypes that people hold can have either beneficial or detrimental effects on their own cognitive and physical development. According to stereotype embodiment theory, ageist stereotypes can

- become internalized across the life span

- operate unconsciously

- become self-

referential - influence a person’s future pathways by having psychological, behavioural, and physiological effects on him or her (Levy, 2009).

495

Having positive or negative age stereotypes can influence people’s actions in an unconscious way. In one study, seniors who were subliminally exposed to negative stereotypes of the elderly, later gave handwriting samples that were noticeably shaky and “senile” looking, whereas those who were exposed to positive images had handwriting that appeared confident and “wise” (Levy, 2000).

Rothermund (2005) found that people who thought of certain behaviours as characteristic of the “typical old person” tended to incorporate those characteristics into their own self-

ESPECIALLY FOR Young Adults Should you always speak louder and slower when talking to a senior citizen?

No. Some seniors hear quite well, and they would resent it.

Some studies have reported that age stereotypes create expectations that act as self-

Ageist EldersMost people older than 70 think they are doing better than other people their age—

Stereotype threat (discussed in Chapter 11) can be as debilitating for the aged as for other groups (Hummert, 2011). For instance, if the elderly fear they are losing their minds, that fear itself may undermine cognitive competence (Hess et al., 2009).

The effect of internalized ageism was apparent in a classic study (Levy & Langer, 1994). The researchers selected three groups. Two were chosen because they might have been less exposed to ageism: residents of China, since older people are traditionally respected and honoured there, and North Americans who had been deaf throughout their lives. The third group was composed of North Americans with typical hearing, who presumably had listened to ageist comments all their lives. In each of these three groups, half the participants were young and half were old.

Memory tests were given to everyone, six clusters in all. Elders in all three groups (Chinese, Americans who are deaf, and Americans who can hear) scored lower than their younger counterparts. This was expected; age differences are common in laboratory tests of memory.

The purpose of this study, however, was not to replicate earlier research, but to see if ageism affected memory. It did. The gap in scores between younger and older North Americans who could hear (those most exposed to ageism) was double that between younger and older North Americans who were deaf, and five times wider than the age gap in the Chinese. Ageism undercut ability, a conclusion also found in many later studies (Levy, 2009). Sadly, later studies have found that, with modernization, many Asian cultures have become more ageist than they were when this earlier research occurred (Nelson, 2011).

When older people believe that they are independent and in control of their own lives, despite the ageist assumptions of others, they are likely to be healthier—

496

Elders must find a way to balance knowing when to persist and do things for themselves and when to seek assistance (Lachman et al., 2011). For instance, at a restaurant, older people should feel no shame in asking a younger dinner companion to read the fine print of a menu, but that younger person should not spontaneously offer to cut the elder’s steak.

Ageism Leading to IllnessAgeism impairs daily life. For example, it prevents depressed older people from seeking help because they resign themselves to infirmity. Could that, as well as a greater reluctance among men than women to ask for help, be why elderly men between the ages of 85 and 89 have the highest suicide rate of any age and either gender (Statistics Canada, 2012h)?

Ageism also leads others to undermine the vitality and health of the aged. For instance, health professionals are less aggressive in treating disease in older patients, researchers testing new prescription drugs enrol few older adults (who are most likely to use those drugs), and caregivers diminish independence by helping the elderly too much (Cruikshank, 2009; Herrera et al., 2010; Peron & Ruby, 2011–

The day–

Ageism may also be a contributing factor to a lower level of exercise among the elderly. In Canada, only 11 percent of those aged 60 to 79 meet recommended guidelines for exercise (2½ hours a week of moderate-

Added to that, self-

None of the normal changes of senescence requires that exercise stop, although some adjustments may be needed (more walking, less sprinting). Health is protected by activity, but ageism in one’s culture, caregivers, and the elderly themselves leads to inaction, then stagnation, and then poor health. Indeed, the passive, immobile elder is at increased risk of virtually every illness.

497

ElderspeakPeople’s stereotypes of the elderly are evident in elderspeak, or the way they talk to the old (Nelson, 2011). Like baby talk, elderspeak uses simple and short sentences, slower talk, higher pitch, louder volume, and frequent repetition. Ironically, elderspeak reduces communication. Higher frequencies are harder for the elderly to hear, stretching out words makes comprehension worse, shouting causes stress and anxiety, and simplified vocabulary reduces the precision of language.

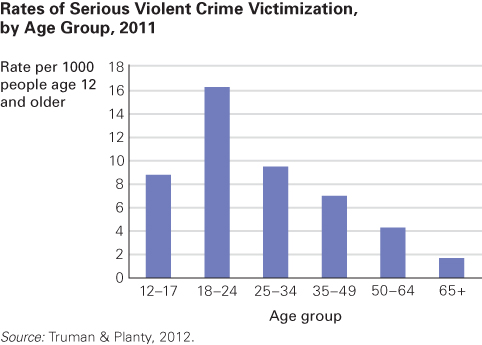

Destructive ProtectionSome younger adults and the media discourage the elderly from leaving home. For example, whenever an older person is robbed, raped, or assaulted, sensational headlines add to fear and, consequently, to ageism. In fact, street crime targets young not older adults (see Figure 14.1). The homicide rate (the most reliable indicator of violent crime, since reluctance to report is not an issue) of those over age 65 is one-

The Demographic Shift

Demography is the science that describes populations, including population by cohort, age, gender, or region. When certain subpopulations become significantly greater or smaller than in past years, this is a demographic shift. In an earlier era, there were 20 times more children than older people, and only 50 years ago, the world had 7 times more people under age 15 than over age 64. No longer.

The World’s Aging PopulationThe United Nations estimates that nearly 8 percent of the world’s population in 2010 was 65 or older, compared with only 2 percent a century earlier. This number is expected to double by the year 2050. Already 13 percent in the United States are that age, as are 14 percent in Canada and Australia, 20 percent in Italy, and 23 percent in Japan (United Nations, 2012).

Demographers often depict the age structure of a population as a series of stacked bars, one bar for each age group, with the bar for the youngest at the bottom and the bar for the oldest at the top. Historically, the shape was a demographic pyramid. Like a wedding cake, it was widest at the base, and each higher level was narrower than the one beneath it, for three reasons—

- More children were born than the replacement rate of one per adult, so each new generation had more people than the previous one.

- Many babies died, which made the bottom bar much wider than later ones.

- Serious illness was usually fatal, reducing the size of each older group.

Sometimes unusual events caused a deviation from this wedding-

That fear evaporated as new data emerged. Birth rates fell and a “green revolution” doubled the food supply. Now people worry about another demographic shift: fewer babies and more elders, affecting world health and politics (Albert & Freedman, 2010). Early death is uncommon; demographic stacks have become rectangles, not pyramids.

498

MITCHELL KANASHKEVICH/CORBIS

The demographic revolution is ongoing, although not yet starkly evident everywhere. Most nations still have more people under age 15 than over age 64. Worldwide, children outnumber elders more than 3 to 1. United Nations predictions for 2015 are for 1 877 551 000 people younger than 15 and 602 332 000 older than 64. Not until 2065 is the ratio projected to be 1 to 1 (United Nations, 2012).

According to Canada’s 2011 National Household Survey, the aging population (65 and older) make up 12.9 percent (4 551 535) of the population; 33.6 percent of this population are immigrants. Over 10 percent are visible minorities, with Chinese (141 650) and South Asians (130 115) the two largest visible minority senior groups (Statistics Canada, 2014d). While about 76.8 percent speak at least one of the official languages, those who do not pose additional challenges for families, communities, and health professionals, who may require translators’ assistance in order to provide adequate and meaningful care and support to the older population (Statistics Canada, 2014a).

Statistics that FrightenUnfortunately, demographic data are sometimes reported in ways designed to alarm. For instance, have you heard that people aged 80 and up are the fastest-

In 2013 in Canada, there were more than 1.4 million people aged 80 and older. Statistics Canada (2013h) estimates that this number could more than double—

But stop and think. According to Statistics Canada, the Canadian population as a whole will also grow over that period, from 33.7 million to about 43.8 million. The percent of residents 80 and older will double, increasing between 2009 and 2036 from 3.8 percent to 7.5 percent (Statistics Canada, 2010d). That proportion will be far from overwhelming for the other 92.5 percent of the population.

Demographers and politicians sometimes report the dependency ratio, estimating the proportion of the population that depends on care from others. This ratio is calculated by dividing the number of dependants (defined as those under age 15 or over age 64) by the number of people in the middle, aged 15 to 64. The highest dependency ratio is in Uganda, with more than one dependant per adult (more than 1 : 1); the lowest is in Bahrain, with one dependant per three adults (1 : 3). Most nations, including Canada and the United States, have a dependency ratio of about 1 : 2 (United Nations, 2012).

499

But the calculation of the dependency ratio assumes that older adults are dependent. Most elders are fiercely independent; they are caregivers not care receivers. In 2007, about one in four caregivers were seniors themselves, with one-

Young, Old, and OldestAlmost everyone overestimates the population in nursing homes because people tend to notice only the frail, not recognizing the rest. This is a characteristic of human thought—

Gerontologists distinguish among the young-

Many of the young-

Ongoing Senescence

The reality that most people over age 64 are quite capable of caring for themselves does not mean that they are unaffected by time. The processes of senescence, described in Chapter 12, continue throughout life. Good health habits slow down aging but do not stop it.

Theories of AgingWhy don’t people stay young? Hundreds of theories and thousands of scientists have sought to understand why aging occurs. To simplify, these theories can be understood in three clusters: wear and tear, genetic adaptation, and cellular aging.

The oldest, most general theory of aging is known as wear and tear. This theory contends that the body wears out, part by part, after years of use. Organ reserve and repair processes are exhausted as the decades pass (Gavrilov & Gavrilova, 2006).

Is this true? For some body parts, yes. Athletes who put repeated stress on their shoulders or knees often have chronically painful joints by middle adulthood; workers who inhale asbestos and smoke cigarettes destroy their lungs. However, many body functions benefit from use. Exercise improves heart and lung functioning; tai chi improves balance; weight training increases muscles; sexual activity stimulates the sexual-

ESPECIALLY FOR Biologists What are some immediate practical uses for research on the causes of aging?

Although ageism and ambivalence limit the funding of research on the causes of aging, many scientists believe that research on cell aging and on the immune system will benefit people of all ages. Such applications include prevention of AIDS, cancer, intellectual decline, and physical damage from pollution.

A second cluster of theories focuses on genes (Sutphin & Kaeberlein, 2011). Humans may have a genetic clock, a mechanism in the DNA of cells that regulates life, growth, and aging. Just as genes start puberty at about age 10, genes may switch on aging. For instance, when a person is injured, aging genes spread the damage, so that an infection spreads rather than being halted and healed (Borgens & Liu-

Evidence for genetic aging comes from premature aging. For example, children born with Hutchinson-

500

Other genes seem to allow an extraordinarily long and healthy life. People who live far longer than the average usually have alleles that other people do not (Halaschek-

Hundreds of genes hasten aging of one body part or another, such as genes for hypertension or many forms of cancer. Certain alleles—

Other alleles are protective. For instance, allele 2 of ApoE aids survival. Of men in their 70s, 12 percent have ApoE2, but of men older than 85, 17 percent have it. This suggests that men with allele 2 are, for some reason, more likely to survive. However, another common allele of the same gene, ApoE4, increases the risk of death by heart disease, stroke, neurocognitive disorder, and—

Why would human genes promote human aging? Evolutionary theory provides an explanation (Hughes, 2010). Societies need young adults to produce the next generation and then need the elders to die (leaving their genes behind) so that the new generation can thrive. Thus, genetic aging may seem harsh to older individuals, but it is actually benevolent for communities.

The third cluster of theories examines cellular aging, focusing on molecules and cells (Sedivy et al., 2008). Toxic substances damage cells over time, so minor errors in copying accumulate (remember, cells replace themselves many times). Over time, imperfections proliferate. The job of the cells of the immune system is to recognize pathogens and destroy them, but the immune system weakens with age as well as with repeated stresses and infections (Wolf, 2010).

Eventually, the organism can no longer repair every cellular error, resulting in senescence. This process is first apparent in the skin, an organ that replaces itself often. The skin becomes wrinkled and rough, eventually developing “age spots” as cell rejuvenation slows down. Cellular aging also occurs inside the body, notably in cancer, which involves duplication of rogue cells. Every type of cancer becomes more common with age because the body is increasingly less able to control the cells.

Even without specific infections, healthy cells stop replicating at a certain point. This is referred to as the Hayflick limit, named after the scientist who discovered this phenomenon. Leonard Hayflick believes that the Hayflick limit, and therefore aging, is caused by a natural loss of molecular fidelity—

One cellular change over time occurs with telomeres—stretches of DNA at the ends of chromosomes that protect the cell’s genetic blueprint. As cells divide, telomeres get shorter. Eventually, at the Hayflick limit, the telomere is gone and cell duplication stops.

Telomere length is about the same in newborns of both sexes and all ethnic groups, but by late adulthood, telomeres are longer in women than in men, and longer in European-

Calorie RestrictionAging slows down in most living organisms with calorie restriction, which is drastically reducing daily calories while maintaining ample vitamins, minerals, and other important nutrients. The benefits of calorie restriction have been demonstrated by research with dozens of creatures, from fruit flies to chimpanzees. Generally, compared with no restrictions, keeping non-

501

Application of calorie restriction to humans is controversial. Controlled experiments with people would be unethical as well as impossible since researchers would have to find hundreds of people, half of whom would be randomly assigned to eat much less than usual, whereas the other half would eat normally. For both groups, periodic checks would ascertain whether they were sticking to their diets and would measure dozens of biomarkers in the blood, urine, heart rate, breathing, and so on.

The researchers would exclude anyone younger than 21 or potentially pregnant since undereating would be particularly harmful to them. They would warn the participants that calorie restriction reduces the sex drive, causes temporary infertility, weakens bones and muscles, affects moods, decreases energy, and probably affects other body functions.

As a result, studies of the effects of calorie restriction on humans have been limited. Researchers have studied populations from places such as Okinawa, Denmark, and Norway, where wartime brought severe calorie reduction plus healthy diets (mostly fresh vegetables). The result was a markedly lower death rate (Fontana et al., 2011). In addition, studies have been conducted with volunteers (not random participants) who choose to reduce their calories. Currently, more than 1000 North Americans belong to the Calorie Restriction Society, voluntarily eating only 1000 nutritious calories a day, none of them buttered or fried. One leader of this group is Michael Rae, from Calgary. He explained:

Aging is a horror and it’s got to stop right now. People are popping antioxidants, getting face-

[quoted in Hochman, 2003, p. A9]

Preliminary data on practitioners of calorie restriction find some health improvements as a result of calorie restriction, but also find somewhat different responses than for non-

All the theories of aging, and all the research on calorie restriction, have not led to any simple way to stop senescence. Most scientists are skeptical, not only of calorie restriction but of what people are willing to give up for a longer life. More than ever, scientists recommend exercise, a moderate diet, and staying away from harmful drugs (especially cigarettes).

Selective Optimization

Social scientists have another goal, not of adding years to life but adding life to years. One method is called selective optimization with compensation (see Chapter 12). The hope is that the elderly will compensate for any impairments of senescence and will excel (optimize) at whatever specific tasks they select. We will look at three examples: sex, driving, and the senses. All three involve personal choice, societal practices, and technological options, but here each is used to illustrate one of these three dimensions of the compensation process.

502

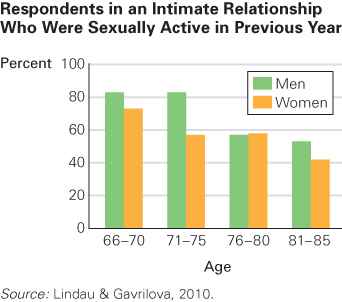

Individual Compensation: SexMost people are sexually active throughout adulthood. Some continue to have intercourse long past age 65 (see Figure 14.2) (Lindau & Gavrilova, 2010). However, on average, intercourse becomes less frequent than it was earlier, often stopping completely. Nonetheless, sexual satisfaction within long-

Many older adults reject the idea that intercourse is the only or even the optimal measure of sexual activity. Instead, if sexual desire remains, then cuddling, kissing, caressing, and fantasizing become more important. Is that optimization, compensation, or both? Desire correlates with sexual satisfaction and quality of life in late adulthood more than frequency of intercourse does (Chao et al., 2011). Indeed, a five-

The research finds that older women, more often than older men, say they have no sexual desire, and, on average, women stop intercourse earlier than men. This is primarily because of a lack of partner availability—

After divorce or death of a partner, selectivity is evident. Some of the elderly prefer to consider sex a thing of the past, some cohabit, some begin LAT (living apart together) with a new partner but without marriage or leaving their own home, and some remarry. That is selective optimization—

Social Compensation: DrivingA life-

Although drivers compensate, few societies do. If an older adult causes a crash, age is blamed rather than other factors, such as the law (Satariano, 2006). Laws are often lax; many jurisdictions renew licences without testing, even at age 80. If testing is required, it often focuses on knowing the rules of the road or being able to read with glasses, not on the characteristics that correlate with accidents. For instance, when vision is tested, it is usually to gauge a person’s face-

Beyond more effective retesting, there are many other things that societies can do. Larger-

Technological Compensation: The SensesEvery sense becomes slower and less sharp with each passing decade (Meisami et al., 2007). This is true for touch (particularly in the fingers), taste (particularly for sour and bitter), smell, and pain, as well as for sight and hearing. Yet in the twenty-

503

Only 10 percent of people of either sex over age 65 see well without glasses (see TABLE 14.1), but selective compensation allows almost everyone to use their remaining sight quite well. Changing the environment—

| • Cataracts. As early as age 50, about 10 percent of adults have cataracts, a thickening of the lens, causing vision to become cloudy, opaque, and distorted. By age 70, 30 percent do. Cataracts can be removed in outpatient surgery and replaced with an artificial lens. |

| • Glaucoma. About 1 percent of those in their 70s and 10 percent in their 90s have glaucoma, a buildup of fluid within the eye that damages the optic nerve. The early stages have no symptoms, but the later stages cause blindness, which can be prevented if an ophthalmologist or optometrist treats glaucoma before it becomes serious. People with diabetes may develop glaucoma as early as age 40. |

| • Macular degeneration. About 4 percent of those in their 60s and about 12 percent over age 80 have a deterioration of the retina, called macular degeneration. An early warning occurs when vision is spotty (e.g., some letters missing when reading). Again, early treatment— |

Similarly, by age 90, the average man is almost deaf, as are about half of the women. For all sensory deficits, an active effort to compensate—

504

Ageism also affects the use or non-

Sensory loss need not lead to morbidity or senility, but without compensation, it can result in less movement and reduced intellectual stimulation. Consequently, illness increases and cognition declines as the senses become less acute.

KEY Points

- Ageism is stereotyping based on age, a prejudice that leads to less competent and less confident elders.

- Demographic changes have resulted in more elders and fewer children in every nation.

- There are many theories of aging, but beyond good health habits, calorie restriction is the only way proven to extend life for some creatures—

but not yet proven in humans. - Elders need not be dependent if they themselves, and others, compensate for whatever difficulties they have.

- Every sense becomes less acute with age, but technology provides many remedies—

if individuals and societies take advantage of them.