14.3 Aging and Disease

As you read in Chapter 12, with each passing decade reaction time slows, the senses become less acute, organ reserves are depleted, and homeostasis takes longer. Skin, hair, and body shape show unmistakable senescence, while every internal organ—

Primary and Secondary Aging

Gerontologists distinguish between primary aging, which involves universal changes that occur with the passage of time, and secondary aging, the consequences of particular inherited weaknesses, chosen health habits, and environmental conditions. One explains:

Primary aging is defined as the universal changes occurring with age that are not caused by diseases or environmental influences. Secondary aging is defined as changes involving interactions of primary aging processes with environmental influences and disease processes.

[Masoro, 2006,p. 46]

Primary aging does not directly cause illness, but it increases the impact of every secondary factor—

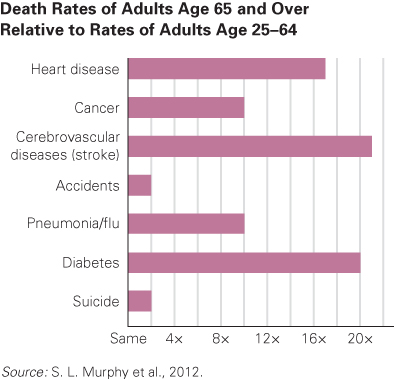

Furthermore, healing takes longer if an illness or an accident occurs (Arking, 2006). For example, young adults who contract pneumonia usually recover in a few weeks, but in the very old the strain of pneumonia over several days can overwhelm a weakened body. Indeed, pneumonia is a leading cause of death for the oldest-

Medical intervention affects the old differently than the young, reducing the effectiveness of drugs, surgery, and so on. For instance, anaesthesia may damage an older person’s brain or may cause the heart to stop. Temporary hallucinations and delirium after surgery are far more common for the old than for the young (Strauss, 2012).

A surprising example of the effects of age comes from medication that reduces hypertension. If systolic blood pressure is above 140, and diet and exercise do not lower it, drugs not only reduce it but also make strokes and heart attacks less likely for middle-

511

A developmental view of the relationship between primary and secondary aging harkens back to the lifelong toll of stress, as explained in Chapter 12. Allostatic load is measured by 10, or even 16, biomarkers—

Thus, measurement of allostatic load assesses the combined, long-

Compression of Morbidity

Ideally, prevention of the diseases of the old begins in childhood and continues throughout life, so societies need to recognize that public health and aging efforts are not only for the older adults of today but also for the future elder generations (Albert & Freedman, 2010). Illness can be delayed, and its severity can be limited by having established good childhood habits. Delayed illness is an example of compression of morbidity, which is reducing (compressing) sickness before death. There is good news here. In recent years, morbidity has been successfully compressed. For instance, unlike 30 years ago, most people diagnosed with cancer, diabetes, or a heart condition continue to be independent for decades (Hamerman, 2007).

Compression of morbidity is a social and psychological blessing as well as a personal, biological one. A healthier person remains alert and active—

The importance of compression of morbidity is apparent with osteoporosis (fragile bones), which occurs because primary aging makes bones more porous, especially if a person is at genetic risk (North American women of European descent are more vulnerable, genetically, than women of other ethnic groups). A fall that would have merely bruised a young person may result in a broken wrist or hip in an elder. That leads to morbidity, sometimes for months, especially when hospitalization and bed rest cause infections and stress.

How can morbidity from osteoporosis be compressed? First, through better health habits earlier in life. Tobacco and alcohol weaken bones, as do low calcium and insufficient weight-

This applies to every kind of primary aging. If the elderly selectively remedy whatever challenges their primary aging presents, morbidity will be compressed.

512

KEY Points

- The diseases that increase with aging can be the direct result of senescence or the accumulated load from years of destructive habits and circumstances.

- Primary aging is inevitable and universal, the direct result of years gone by. Secondary aging involves diseases that result from poor health habits, genetic vulnerability, infections, and toxic substances.

- To improve the quality of later years, it is important to reduce the debilitation caused by chronic diseases, a goal called compression of morbidity. As illustrated with osteoporosis, aging need not be accompanied by years of debilitating disease.