14.4 Neurocognitive Disorders

The patterns of cognitive aging challenge another assumption: that older people always lose the ability to think and remember. That is not true. Many older people are less sharp than they were, but are still quite capable of intellectual activity. Others experience serious decline.

The Ageism of Words

It is undeniable that the rate of neurocognitive disorders increases with every decade after age 70. To understand that and prevent the worst of it, caution is needed in using words. Formerly, senility was used to mean severe mental impairment, which implied that old age always brings intellectual failure—

Memory impairment is common in every cognitive disorder, although symptoms of neurocognitive disorders include many more problems, especially in learning new material, using language, moving the body, and responding to people. Practical challenges include getting lost, becoming confused about using common objects like a telephone or toothbrush, or having extreme emotional reactions.

The lines between normal age-

The problem of ageist terminology has been recognized internationally. In Japanese, the traditional word for neurocognitive disorder was chihou, translated as “foolish” or “stupid.” As more people reached old age, the Japanese decided on a new word, ninchihou, which means “cognitive syndrome” (George & Whitehouse, 2010). That is similar to the changes in English terminology over the past decades, from senility to dementia to neurocognitive disorder.

Mild and Major Impairment

Many instances of memory loss are not necessarily ominous signs of severe loss to come. Older adults who have significant problems with memory, but who still function well at work and home, might be diagnosed with mild NCD, formerly called mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Although some of these adults will develop major disorders, about half will be mildly impaired for decades or will regain cognitive abilities (Lopez et al., 2007; Salthouse, 2010).

513

Many tests are designed to measure mild loss, including one that takes less than 10 minutes—

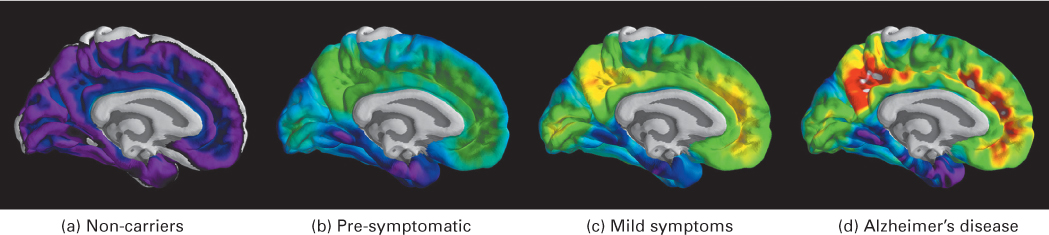

Many scientists seek biological indicators (called “biomarkers”), such as substances in the blood or cerebrospinal fluid, or brain indicators (as found in brain scans) that predict major memory loss. However, although abnormal scores on many tests (biological, neurological, or psychological) indicate possible problems, an examination of 24 such measures found no single test, and no combination of tests, to be 100 percent accurate (Ewers et al., 2012).

The final determinant of neurocognitive disorders is the clinical judgment of a professional who considers all the symptoms and markers—

Prevalence of NCD

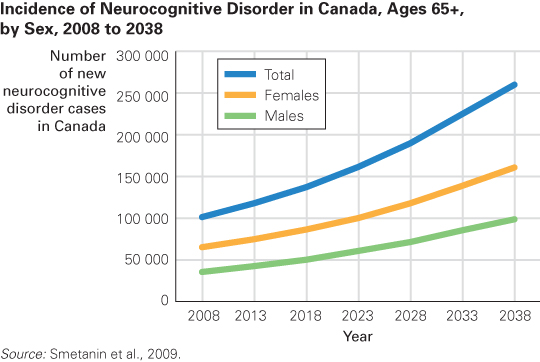

According to the Alzheimer Society of Canada, in 2011, 747 000 Canadians were living with some form of cognitive impairment, including NCD, which accounted for about 14.9 percent of Canadians aged 65 and older (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2012). (Figure 14.5 shows the predicted number of new cases of NCD in Canada each year until 2038.) Rates of NCD vary by nation, from about 2 to 25 percent of elders, with an estimated 35 million people affected worldwide (Kalaria et al., 2008; WHO, 2012). Developing nations have lower rates, but that may be because millions of people in the early stages are not counted or because health care overall is poor.

How would poor health care lead to less, not more, impairment? Because many people die before any neurocognitive problems are apparent. People with diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, strokes, and heart surgery are more likely to lose intellectual capacity in old age, but in poor nations many people with those conditions die before age 70.

Improvements in health care can reduce cognitive impairment. The three ideal goals of public health are said to be better physical health, less mental disorder, and longer lives. That is becoming a reality in some nations. In England and Wales, the rate of NCD for people over age 65 was 8.3 percent in 1991 but only 6.5 percent in 2011 (Matthews et al., 2013). Sweden had a similar decline (Qiu et al., 2013). In China, rates were much higher in rural areas than in urban ones, probably because rural Chinese had less education (Jia et al., 2014) and, thus, less understanding about how to stay healthy. A comparable survey has not been done in North America, but some signs suggest improvement.

Of course, reduction in rate does not necessarily mean reduction in number, since more people live to old age. In England over the past 20 years, the number of people with NCD has stayed about the same (Matthews et al., 2013) even while the rate has declined.

514

Genetics and social context affect rates, but it is not known by how much (Bondi et al., 2009). For example, more older women than older men are diagnosed with neurocognitive disorders, which may be genetic, educational, or stress-

Now consider some specific types of age-

Alzheimer’s DiseaseIn 1906, a physician named Dr. Alois Alzheimer performed an autopsy on a patient who had lost her memory. He found unusual material in her brain, but he was uncertain whether it specified a distinct disease (George & Whitehouse, 2010). Others, convinced that he had discovered a disease, named it after him. In the past century, millions of people in every large nation have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), now formally referred to as major or mild NCD due to Alzheimer’s disease. (See TABLE 14.2 for the stages of Alzheimer’s disease.) In China, for example, 5.7 million people have Alzheimer’s disease (K.Y. Chan et al., 2013).

|

Stage 1. People in the first stage forget recent events or new information, particularly names and places. For example, they might forget the name of a famous film star or how to get home from a familiar place. This first stage is similar to mild cognitive impairment— |

|

Stage 2. Generalized confusion develops, with deficits in concentration and short- |

|

Stage 3. Memory loss becomes dangerous. Although people at stage 3 can care for themselves, they might leave a lit stove or hot iron on or might forget whether they took essential medicine and thus take it twice— |

|

Stage 4. At this stage, full- |

| Stage 5. Finally, people with AD become unresponsive. Identity and personality have disappeared. Death comes 10 to 15 years after the first signs appear. |

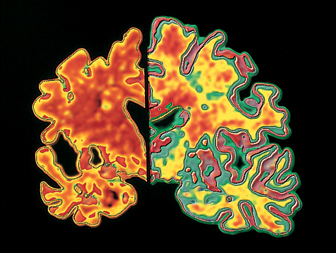

As Dr. Alzheimer discovered, autopsies reveal that some aging brains have many plaques and tangles in the cerebral cortex. These abnormalities destroy the ability of neurons to communicate with one another, causing severe cognitive loss. Plaques are clumps of a protein called beta-

Although finding massive brain plaques and tangles at autopsy proves that a person diagnosed with NCD had Alzheimer’s disease, between 20 and 30 percent of cognitively normal elders have, at autopsy, the same level of plaques in their brains as people who had been diagnosed with AD (Jack et al., 2009). Possibly the elders who had not been diagnosed with NCD had compensated by using other parts of their brains; possibly they were in the early stages, not yet suspected of having AD; possibly plaques are a symptom, not a cause.

Alzheimer’s disease is partly genetic. If it develops in middle age, the affected person either has trisomy-

Most cases begin much later, at age 75 or so. Many genes have some impact, including SORL1 and ApoE4 (allele 4 of the ApoE gene). People who inherit one copy of ApoE4 have about a 50/50 chance of developing AD. Those who inherit two copies almost always develop the disorder if they live long enough.

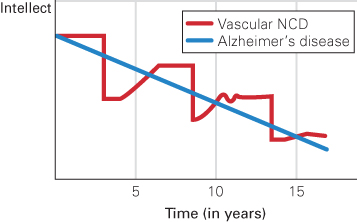

Vascular NCDThe second most common cause of neurocognitive disorder is a stroke (a temporary obstruction of a blood vessel in the brain) or a series of strokes, called transient ischemic attacks (TIAs, or ministrokes). The interruption in blood flow reduces oxygen, destroying part of the brain. Symptoms (blurred vision, weak or paralyzed limbs, slurred speech, and mental confusion) suddenly appear.

515

In a TIA, symptoms may vanish quickly, unnoticed. However, unless it is recognized and preventive action is taken, another is likely. Repeated TIAs produce a type of NCD sometimes called vascular neurocognitive disorder. The progression of vascular NCD differs from Alzheimer’s disease, but the final result is similar (see Figure 14.6).

Neurocognitive disorders caused by vascular disease are apparent in many of the oldest-

Frontal Lobe DisordersSeveral types of neurocognitive disorders are called frontal lobe disorders, or frontotemporal lobar degeneration. (Pick’s disease is the most common form). These disorders are particularly likely to occur at relatively young ages (under age 70), unlike Alzheimer’s disease and vascular NCD, which typically begin later (Seelaar et al., 2011).

In frontal lobe disorders, parts of the brain that regulate emotions and social behaviour (especially the amygdala and prefrontal cortex) deteriorate. Emotional and personality changes are the main symptoms (Seelaar et al., 2011). A loving father with frontal lobe degeneration might reject his children, or a formerly astute businesswoman might invest in a hare-

Frontal lobe problems may be worse than more obvious types of neurocognitive disease in that compassion, self-

threw away tax documents, got a ticket for trying to pass an ambulance, and bought stock in companies that were obviously in trouble. Once a good cook, he burned every pot in the house. He became withdrawn and silent, and no longer spoke to his wife over dinner. That same failure to communicate got him fired from his job.

[Grady, 2012, p. A1]

Finally, he was diagnosed with frontal lobe disorder. Ruth asked him to forgive her fury. It is not clear that he understood either her anger or her apology.

516

Although there are many forms and causes of frontal lobe disorders—

Other DisordersMany other brain diseases begin with impaired motor control (shaking when picking up a coffee cup, falling when trying to walk), not with impaired thinking. The most common of these is Parkinson’s disease, the cause of about 3 percent of all cases of NCD (Aarsland et al., 2005).

Parkinson’s disease starts with rigidity or tremor of the muscles as dopamine-

Another 5 to 15 percent of Canadians with NCD suffer from an excess of Lewy bodies: deposits of a particular kind of protein in their brains. Lewy bodies are also present in Parkinson’s disease, but in Lewy body disease they are more numerous and dispersed throughout the brain, interfering with communication between neurons. As a result, movement and cognition are both impacted, although motor effects are less severe than in Parkinson’s disease and memory loss is not as dramatic as in Alzheimer’s disease (Bondi et al., 2009). The main symptom is loss of inhibition: A person might gamble or become hypersexual.

Comorbidity is common with all these disorders. For instance, most people with Alzheimer’s disease also show signs of vascular impairment (Doraiswamy, 2012). Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and Lewy body disease can occur together: People who have all three experience more rapid and severe cognitive loss (Compta et al., 2011).

Some other types of NCD begin in middle age or even earlier, caused by Huntington disease, multiple sclerosis, a severe head injury, or the last stages of syphilis, AIDS, or bovine spongiform encephalitis (BSE, or mad cow disease). Repeated blows to the head, even without concussions, can cause chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which first causes memory loss and emotional changes, and eventually further cognitive loss (Voosen, 2013). Although the rate of systemic brain disease increases dramatically with every decade after age 60, brain disease can occur at any age, as revealed by the autopsies of a number of young professional athletes. For athletes, prevention includes better helmets and fewer body blows.

Preventing Impairment

Since aging increases the rate of cognitive impairment, slowing down senescence may postpone major neurocognitive disorders, and ameliorating mild losses may prevent worse ones. That may have occurred in the decreasing rates of major NCD documented in England (Matthews et al., 2013).

Epigenetic research is particularly likely to lead to better prevention, because “the brain contains an epigenetic ‘hotspot’ with a unique potential to not only better understand its most complex functions, but also to treat its most vicious diseases” (Gräff et al., 2011). Genes are always influential. Some are expressed, affecting development, and some are latent unless circumstances change. The reasons are epi-

The most important non-

517

Medication to prevent stroke also protects against neuro-

Avoiding specific pathogens is critical. For example, beef can be tested to ensure that it does not have BSE, condoms can protect against AIDS, and syphilis can be cured with antibiotics. For most neurocognitive disorders, however, despite the efforts of thousands of scientists and millions of older people, no foolproof prevention or cure has been found. Avoiding toxic substances (lead, aluminum, copper, and pesticides) and adding supplements (hormones, aspirin, coffee, insulin, anti-

Thousands of scientists have sought to halt the production of beta-

Among professionals, hope is replacing despair. Earlier diagnosis seems possible; many drug and lifestyle treatments are under review (Hampel et al., 2012; Lane et al., 2011). The first step, however, in prevention and treatment of NCD is to improve overall health. High blood pressure, diabetes, arteriosclerosis, and emphysema all impair cognition, because they disrupt the flow of oxygen to the brain. Each type of neurocognitive disorder, each slowdown, and every chronic disease interact, so progress in one area may reduce incidence and severity in another. A healthy diet, social interaction, and, especially, exercise decrease cognitive impairment of every kind, affecting brain chemicals and encouraging improvement in other health habits.

Reversible Neurocognitive Disorder?

Sometimes memory and other problems are not the result of a neurocognitive disorder. Older people may be thought to be permanently “losing their minds,” when in fact a reversible condition is at fault. This highlights the importance of an accurate diagnosis.

Depression and AnxietyThe most common reversible condition that is mistaken for neurocognitive disorder is depression. Normally, older people tend to be quite happy; frequent sadness or anxiety is not normal. Ongoing, untreated depression increases the risk of NCD (Y. Gao et al., 2013).

Ironically, people with untreated anxiety or depression may exaggerate minor memory losses or refuse to talk. Quite the opposite reaction occurs with early Alzheimer’s disease, when victims are often surprised when they cannot answer questions, or with Lewy body or frontal lobe disorders, when people talk without thinking.

518

Specifics provide other clues. People with neurocognitive loss might forget what they just said, heard, or did because current brain activity is impaired, but they might repeatedly describe details of something that happened long ago. The opposite may be true for emotional disorders, when memory of the past is impaired but short-

NutritionMalnutrition and dehydration can also cause symptoms that may seem like brain disease. The aging digestive system is less efficient but needs more nutrients and fewer calories. This requires new habits, less fast food, and more grocery money (which many do not have). Some elderly people deliberately drink less because they want to avoid frequent urination, yet adequate liquid in the body is needed for cell health. Since homeostasis slows with age, older people are less likely to recognize and remedy their hunger and thirst, and thus may inadvertently impair their cognition.

Additionally, several specific vitamins, including antioxidants (C, A, E) and vitamin B-

Indeed, well-

PolypharmacyAt home as well as in the hospital, most elderly people take numerous drugs—

Unfortunately, recommended doses of many drugs are determined primarily by clinical trials with younger adults, for whom homeostasis usually eliminates excess medication (Herrera et al., 2010). When homeostasis slows down, excess may linger. In addition, most trials to test the safety of a new drug exclude people who have more than one disease. That means drugs are not tested on many of the elderly who will use them, so recommended dosages may not be appropriate for them.

The average elderly person in Canada sees a doctor several times a year. Typically, each doctor follows “clinical practice guidelines,” which are recommendations for one specific condition. A “prescribing cascade” (when many interacting drugs are prescribed) may occur. In one disturbing case, a doctor prescribed medication to raise his patient’s blood pressure, and another doctor, noting the raised blood pressure, prescribed a drug to lower it (McLendon & Shelton, 2011–

Another problem is that people of every age forget when to take which drugs (before, during, or after meals? after dinner or at bedtime?), a problem multiplied as more drugs are prescribed (Bosworth & Ayotte, 2009). Short-

519

Finally, following recommendations from the radio, friends, and television ads, many of the elderly try supplements, compounds, and herbal preparations that contain mind-

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Too Many Drugs or Too Few?

The case for medication is persuasive. Thousands of drugs have been proven effective, many of them responsible for longer and healthier lives. It is estimated that, on doctor’s orders, 20 percent of older people take 10 or more drugs on a regular basis (Boyd et al., 2005). Common examples of life-

In addition, many older people take supplements, drink alcohol, and swallow vitamins and other non-

was covered with large black bruises and burns from her kitchen stove. Audrey no longer had an appetite, so she ate little and was emaciated. One night she passed out in her driveway and scraped her face. The next morning, her neighbor found her face down on the pavement in her nightgown.

Audrey couldn’t be trusted with the grandchildren anymore, so family visits were fewer and farther between. She rarely showered and spent most days sitting in a chair alternating between drinking, sleeping, and watching television. She stopped calling friends, and social invitations had long since ceased.

Audrey obtained prescriptions for Valium, a tranquilizer, and Placidyl, a sleep inducer. Both medications, which are addictive and have more adverse effects in patients over age 60, should be used only for short periods of time. Audrey had taken both medications for years at three to four times the prescribed dosage. She mixed them with large quantities of alcohol. She was a full-

Her children knew she had a problem, but they…couldn’t agree among themselves on the best way to help her. Over time, they became desensitized to the seriousness of her problem—

[Colleran & Jay, 2003]

Audrey is a stunning example of the danger of ageist assumptions—

The solution seems simple: Discontinue drugs. However, that may increase both disease and neurocognitive disorders. One expert criticizes polypharmacy but adds that “underuse of medications in older adults can have comparable adverse effects on quality of life” (Miller, 2011–

For instance, untreated diabetes and hypertension cause cognitive loss. Lack of drug treatment for those conditions may be one reason why low-

Obviously, money complicates the issue: Prescription drugs are expensive, which increases profits for drug companies, but they can also reduce surgery and hospital stays, thus saving money. As one observer notes, the discussion about spending for prescription drugs is highly polarized, emotionally loaded, with little useful debate. A war is waged over the cost of prescriptions for older people, and it is a “gloves-

Which is it—

The current policy is to let the doctor and the patient decide. Even family members are not consulted or informed unless the patient agrees. That seems like a wise protection of privacy. But remember Audrey.

520

KEY Points

- Many elderly people experience some cognitive impairment, which may lead to neurocognitive disorder (NCD), formerly called dementia.

- Among the many types of NCD, each with distinct symptoms, are four common diseases of the elderly: Alzheimer’s disease, vascular NCD, frontal lobe disorder, and Parkinson’s disease.

- No cure for NCD has yet been found, but treatment may slow its progression and sometimes prevent its onset.

- The best prevention and treatment is exercise, although drugs, nutrition, and other measures may also be helpful.

- The elderly are sometimes thought to suffer from NCD when in fact they have other problems, especially depression, alcoholism, malnutrition, or polypharmacy.