14.5 New Cognitive Development

You have learned that most older adults maintain adequate intellectual power. Some losses—

Erikson and Maslow

Both Erik Erikson and Abraham Maslow were particularly interested in the elderly, interviewing older people to understand their views. Erikson’s final book, Vital Involvement in Old Age (Erikson et al., 1986), written when he was in his 90s, was based on responses from other 90-

Erikson found that many older people gained interest in the arts, in children, and in human experience as a whole. He said elders are “social witnesses,” aware of the interdependence of the generations as well as of all of human experience. His eighth stage, integrity versus despair, is the time when life comes together in a “re-

Maslow maintained that older adults are more likely than younger people to reach the highest stage of development, self-actualization. Remember that Maslow rejected an age-

The stage of self-

521

Aesthetic Sense and Creativity

For many, old age can be a time of emotional sensory awareness and enjoyment (R. N. Butler et al., 1998). For that reason, some of the elderly take up gardening, bird watching, sculpting, painting, or making music, even if they have never done so before.

An example of late creative development is the American artist Anna Moses, who was a farm wife in rural New York. For most of her life, she expressed her artistic impulses by stitching quilts and embroidering in winter, when farm work was slow. At age 75, arthritis made needlework impossible, so she took to “dabbling in oil.” Four years later, three of her paintings, displayed in a local drugstore, caught the eye of a New York City art dealer who happened to be driving through town. He bought them, drove to her house, and bought 15 more. The following year, at age 80, “Grandma Moses” had a one-

PIERRE BESSARD/REA/REDUX

Other well-

In a study of extraordinarily creative people, almost none felt that their ability, their goals, or the quality of their work had been much impaired by age. The leader of that study observed, “In their seventies, eighties, and nineties, they may lack the fiery ambition of earlier years, but they are just as focused, efficient, and committed as before…perhaps more so” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996).

522

The creative impulse is one that family members and everyone else should encourage in the elderly, according to many professionals. Expressing one’s creativity and aesthetic sense is said to aid in social skills, resilience, and even brain health (McFadden & Basting, 2010).

The same can be said for the life review, in which elders provide an account of their personal journey by writing or telling their story. They want others to know their history, telling not solely about themselves but also about their family, cohort, or ethnic group. A leading gerontologist wants us to listen:

We have been taught that this nostalgia represents living in the past and a preoccupation with self and that it is generally boring, meaningless, and time-

[R. N. Butler et al., 1998]

Wisdom

In a massive international survey of 26 nations, at least one on each inhabited continent, researchers found that most people everywhere agree that wisdom is a characteristic of the elderly (Löckenhoff et al., 2009). One reviewer contends that “wise elders might become a valuable asset for a more just and caring future society” (Ardelt, 2011). Yet another reviewer offers a different opinion: The idea that older people are wise is a “hoped-

An underlying research quandary is that a universal definition of wisdom is elusive: Each culture and each cohort has its own concept, with fools sometimes seeming wise (as in many Shakespearean plays). Older and younger adults differ in how they make decisions; one interpretation of these differences is that the older adults are wiser, but not every younger adult would agree (Worthy et al., 2011).

One summary describes wisdom as an “expert knowledge system dealing with the conduct and understanding of life” (P. B. Baltes & Smith, 2008). Several factors just mentioned, including the ability to put aside one’s personal needs (as in self-

The popular consensus may be grounded in reality. Two psychologists explain:

Wisdom is one domain in which some older individuals excel.…[They have] a combination of psychosocial characteristics and life history factors, including openness to experience, generativity, cognitive style, contact with excellent mentors, and some exposure to structured and critical life experiences.

[P. B. Baltes & Smith, 2008]

These researchers posed life dilemmas to adults of various ages and asked others (who had no clue as to how old the participants were) to judge whether the responses were wise. They found that wisdom is rare at any age, but, unlike physical strength and cognitive quickness, wisdom does not fade with maturity. Thus, some people of every age were judged as wise.

523

Similarly, the author of a detailed longitudinal study of 814 people concludes that wisdom is not reserved for the old, and yet humour, perspective, and altruism increase over the decades, gradually making people wiser. He then wrote:

To be wise about wisdom we need to accept that wisdom does—

[Vaillant, 2002]

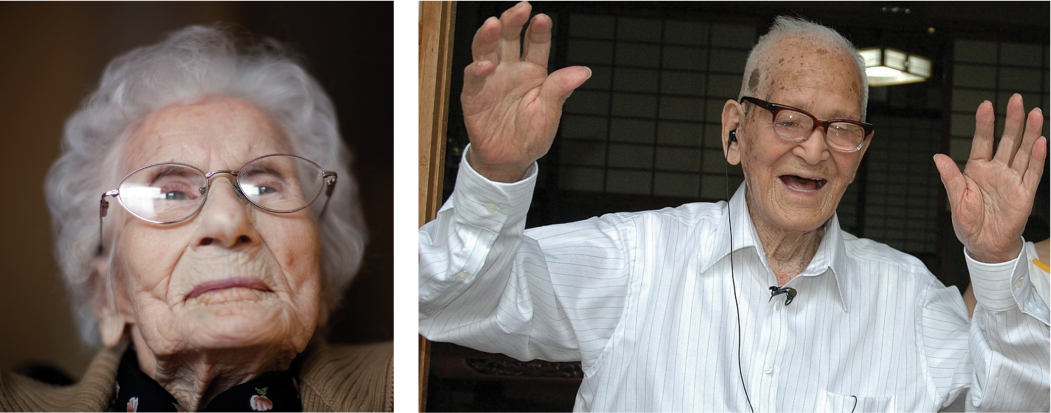

The Centenarians

If age brings integrity, creativity, and maybe even wisdom, then the oldest-

Other Places, Other StoriesIn the 1970s, three remote places—

Most of the aged work regularly… Some even continue to chop wood and haul water. Close to 40 percent of the aged men and 30 percent of the aged women report good vision; that is, that they do not need glasses for any sort of work, including reading or threading a needle. Between 40 and 50 percent have reasonably good hearing. Most have their own teeth. Their posture is unusually erect, even into advanced age. Many take walks of more than two miles a day and swim in mountain streams.

[Benet, 1974]

A more comprehensive study (Pitskhelauri, 1982) found that the lifestyles in all three of these regions were similar in four ways:

- Diet. People ate mostly fresh vegetables and herbs, with little meat or fat. They thought it better to be a little bit hungry than too full.

- Work. Even the very old did farm work, household tasks, and child care.

- Family and community. The elderly were well integrated into families of several generations and interacted frequently with friends and neighbours.

- Exercise and relaxation. Most took a walk every morning and evening (often up and down mountains), napped midday, and socialized in the evening.

Perhaps these factors—

THE ASAHI SHIMBUN/GETTY IMAGES

The Truth About Life After 100Insights gained from the studies of the three regions famous for long-

As for preventing the ills of old age, it does seem that exercise, diet, and social integration add a few years to the average life, but not decades. It is important to distinguish the average life span from the maximum.

524

Genes seem to bestow on every species an inherent maximum life span, defined as the oldest possible age for members of that species (Wolf, 2010). Under ideal circumstances, the maximum that rats live seems to be 4 years; rabbits, 13; tigers, 26; house cats, 30; brown bats, 34; brown bears, 37; chimpanzees, 55; Indian elephants, 70; finback whales, 80; humans, 122; lake sturgeon, 150; giant tortoises, 180.

Maximum life span is quite different from average life expectancy, which is the average life span of individuals in a particular group. In human groups, average life expectancy varies a great deal, depending on historical, cultural, and socioeconomic factors as well as on genes (Sierra et al., 2009). Recent increases in life expectancy are attributed to the reduction in deaths from adult diseases (heart attack, pneumonia, cancer, childbed fever).

In Canada from 2007 to 2009, average life expectancy at birth was about 79 years for men and 83 years for women. That is much longer than from 1980 to 1982, when the average life expectancy for men was 72 years and for women 79 years (Statistics Canada, 2012c). How long can average life expectancy keep increasing?

Gerontologists are engaged in a debate as to whether the average life span will keep rising and whether the maximum is genetically fixed and our society has just about reached that (Couzin-

Everyone agrees, however, that the last years of life can be good ones. Those who study centenarians find many quite happy (Jopp & Rott, 2006). Jeanne Calment enjoyed a glass of red wine and some olive oil each day. “I will die laughing,” she said.

Disease, disability, depression, and neurocognitive disorder may eventually set in; studies disagree about how common these problems are past age 100. Some studies find a higher rate of physical and mental health problems before age 100 than after. For example, in Sweden, where medical care is free, researchers found that centenarians were less likely to take antidepressants, but more likely to use pain medication, than those who were aged 80 or so (Wastesson et al., 2012).

Could centenarians be happier than octogenarians, as these Swedish data suggest? That is not known. However, it is true that more and more people live past 100, and many of them are energetic, alert, and optimistic (Perls, 2008; Poon, 2008). Social relationships in particular correlate with robust mental health (Margrett et al., 2011). Centenarians tend to be upbeat about life. Whether their attitude is justified is not clear. Remember, however, that ageism affects all of us. As explained in the beginning of this chapter, ageism shortens life and makes the final years less satisfying. Don’t let it. As thousands of centenarians demonstrate, a long life can be a happy one.

525

KEY Points

- Old age may be a time of integrity and self-

actualization, although this is not always the case. - Many older people are more creative than they were earlier in life, enjoying art and music.

- Wisdom is thought to correlate with experience, although research finds that some people are wise long before old age, and most people are never wise.

- The number of centenarians is increasing, as the average but not the maximum life span increases; some of those over age 100 are active, independent, and happy.